Radio de Acción: Violent Circuits, Contentious Voices: Caribbean Radio Histories

This month Sounding Out! inaugurates a four-part series slated to appear on the Thursday stream into May entitled “Radio de Acción”: Broadcasting in Latin America and the Caribbean, edited by Cornell Assistant Professor in Comparative Literature Tom McEnaney.

Tom has been a key contributor to SO! over the years — check out his articles on Orson Welles and Twin Peaks, two excellent and vivid pieces I wish I could’ve written. We’re excited to have Tom as our guide to the many frequencies of Latin American and Caribbean radio, helping us “tune North American antennas South for a while,” as he proposes in his series introduction below. Gather round, dear listeners, I think the transmission’s about to start …

— SCMS/ASA Special Editor Neil Verma

—

It’s difficult to keep the radius of radio within national boundaries. Or so it has often seemed in the Americas. The first Argentine broadcast, on August 27, 1920, transmitted a performance of Wagner’s Parisfal that accidentally reached ships in Brazil. Border radio in Spanish and English has bled across the frontiers between Mexico and the United States since at least the early 1930s. And if listeners from Alabama to Washington State tuned their shortwave receivers right in the early 1960s, they would have heard the exiled civil rights activists Robert F. and Mabel Williams’ famous tag line: “You are tuned to Radio Free Dixie, from Havana, Cuba, where integration is an accomplished fact.”

In Spanish, “radio” can mean the sonic broadcasting it denotes in English, but also radium, the spoke of a wheel, a radius (and the bone of the same name), an orbit, or a sphere of influence. Our series title, Radio de Acción, plays on an inter-linguistic pun, which takes the “radius of action” or “area of operations” the phrase connotes in Spanish, and thinks of radio broadcasting as changing the cultural, historical and political fields it engages through particular types of “radio action.”

Acknowledging language’s role in widening or narrowing that radius, the four posts in this special series help tune our ears to a diversity of voices from Latin America and the Caribbean. Over the next few months Radio de Acción will explore the multilingual history of radio in the Caribbean, an Aymara / Spanish talk show in Bolivia, a Cuban-born writer’s radio dramas produced in German, and the Spanish / English radio program Radio Ambulante, which its creators describe as “This American Life, but in Spanish, and transnational.” Featuring posts from Alejandra Bronfman, Karl Swinehart, and Carolina Guerrero, our series sets out to turn North American antennas South for a while.

I’m especially excited to begin the series by welcoming University of British Columbia History Professor, Alejandra Bronfman, whose extraordinary story of radio in the Caribbean below serves as an ideal overture to Radio de Acción. Don’t move that dial.—

— TM

—

The most striking example of radio’s power in the political dramas of the Caribbean took place in Havana, Cuba in March of 1957. A group of student activists opposed to the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista’s regime attempted to assassinate him and simultaneously occupied one of Havana’s most popular stations, Radio Reloj. Locking out the broadcasters, who usually spent the day reading the news and announcing the time every minute on the minute, the activists declared Batista’s death, and their victory. It may be that their plan depended precisely on the uncertainty they created. Whether Batista was actually dead mattered less than the reaction they hoped to incite with their declaration. Batista did not die that day; the students’ plot was foiled; and the attempt ended in death for most of the assailants. However, the failure was only temporary—another group of radio rebels would overthrow Batista less than two years later—and the 1957 takeover cemented radio’s undisputed role as bearer of truth and center of power.

In this post I consider radio’s relationship to violence in connection to its creation of truth, mendacity and illusion. Radio publics in the Caribbean emerged amidst conflict, and, as the 2000 assassination of the Haitian broadcaster Jean Dominique suggests, there is still much at stake in their existence as arbiters of political practice and cultural affiliation.

In the earliest years, radio competed for attention in Caribbean soundscapes full of talk and music rooted in the legacies of slavery. In Haiti, a US occupation (1915-1934) coincided with the development of wireless technology by the US military. Military officials understood the potential of wireless for communication among ships. When US marines landed in Port-au-Prince in 1915, they immediately landed a radio set as well. Although wireless linked the marines to their passing ships, it was not yet a cultural medium sustaining a connection to familiar songs and voices. Haiti was a confusing, disorienting place for many of them: some were disappointed to have been sent there rather than the European front of WWI, others raised in the American South were appalled at the power and status of Haitians of African descent. As remembered by one marine, the sound of Haiti could terrify: “No movies, no radio, none of the features of civilized life to which he was accustomed… Drums boomed continuously. …the drums seemed to him to be the voice of the evil one, always booming in his ears, threatening him, tempting him.”

Most confusing of all was the language. 90% of Haitians spoke Kreyol, which is not French, and not like anything the marines had probably heard before. Documents of the occupation record their efforts to turn what they heard as noise into comprehensible signals. They understood how crucial it would be to obtain information from market women, whose perambulations through the countryside, in weekly walks from their villages to market towns, allowed them to gather news and gossip. If they could convince these women to become informants, and then use radio to relay crucial knowledge between strategic points–the terrain was difficult, with paths rather than roads and frequent rain and flash flooding made travel unpredictable—they might somehow begin to locate and crush insurgencies. The installation of radios signaled the Marines’ efforts to exercise control and insert themselves into these circuits of talk and rumor. But results were paltry. Documents from the early phase of the occupation speak to unreliable technology, lack of knowledge about how to use it, its burdensome heft (radio sets had to be hauled by donkeys through the dense forests), and frequent sabotage.

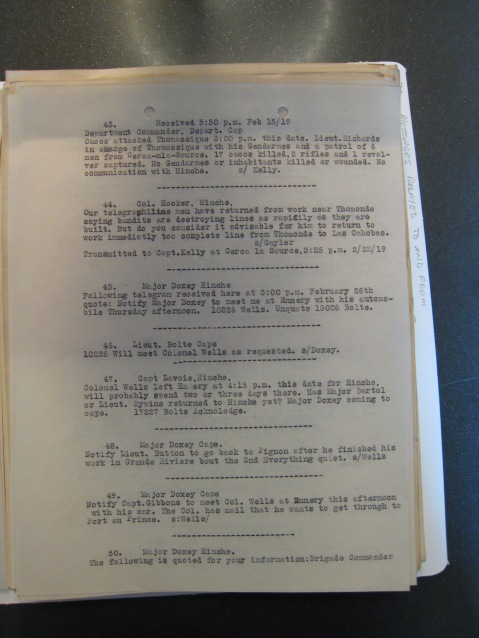

“Messages relayed to and from Cap Haitien via Ouanaminthe”, Entry 173 Chief of the Gendarmerie D’ Haiti, General Correspondence 1919-1920, Operations against hostile bandits, RD 127, United States National Archives

They also speak to desperation and macabre inventiveness in the face of fear. Some Marines discovered that they could try getting the ‘truth’ out of Haitians in novel ways. They applied wires from radio sets to Haitian people’s bodies, and shot electric current through them during interrogation sessions, hoping to use their “new media” to simultaneously terrorize bodies and extract information from them. Electrotorture enacted, literally, the relationship between technology, the production of knowledge and imperial violence.

“Rádio que Che transmitia programas revolucionários enquanto estava entocado na montanha” by Flickr user Marco Gomes, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The histories of radio played out in different registers elsewhere in the Caribbean. While Haiti eventually acquired a broadcasting station in 1926, there was no local radio in Jamaica until 1939.. British colonial officials, distracted by their bloated empire and feeling the economic pinch in any case, had no appetite for building a local station, though Kingston’s residents frequently called for one. While wealthy residents of Jamaica who could afford shortwave receivers had the world at their fingertips—the BBC, US programs, music from Cuba’s powerful stations—the majority of Jamaicans listened instead to their own voices in songs and popular theater, mostly in Jamaican patois.

As the British Empire relegated Jamaica to the margins, capital, people, and many sounds came from the US. Indeed, strapped British officials conscripted amateur radio operators and their US-bought equipment for state purposes. When passing British ships needed to test communications, they asked amateurs to donate their time and expertise. The most prominent of those, the New Yorker John Grinan, achieved some fame in the ham radio world for his experiments with shortwave radio. A participant in the first exchange of transatlantic signals, and one of the operators who helped relay Tom Heeney’s 1928 boxing match against Gene Tunney between New York and New Zealand (via Jamaica), Grinan lent his technological expertise to the British. When striking Jamaican workers cut telephone and telegraph lines amidst labor unrest in the summer of 1938 colonial officials, lacking access to wireless equipment, asked amateur operators like Grinan to police the rebellion, relaying whatever information they could from their rural stations to Kingston.

In the aftermath, colonial officials hoped the new radio station, created with equipment donated by Grinan, would provide a means of calming the unruly masses through educational broadcasting. But the new station’s programming was so dull, and receivers were so expensive and so unreliable, that few listened. It was only in the late 1950s, through the contributions of people like the actress, writer, and radio personality Louise Bennett that the sounds of patois eased radio’s participation into voluble soundscapes long populated by sound systems, music and talk.

As Bennett joked and chided in patois and local musicians like Bob Marley finally got air time, their performances rescued radio from its elitist roots and people finally tuned in.

By that time in Cuba, both the government and its opposition knew that controlling radio meant wielding power, or at least creating the illusion of that power. Cuba’s commercial ties to the US meant that it took part in its neighbor’s vociferous radio culture. Ads, radios, programs and music crisscrossed the Atlantic and shaped transnational listening. By the 1930s, a large radio public tuned in regularly to radionovelas, music and news available throughout the day. So it seemed to make perfect sense when governments claimed airspace to propagate messages and dissenters tampered with communications networks or deployed underground broadcasts—often from outside of Cuba—to convey their discontent. It was this radio world in which students decided that in order to topple a dictator you needed to occupy a radio station.

“Before going to sleep, Pepito and Bebita listen to a story transmitted by their grandfather, from New York or Chicago.” “Carteles,” January 1923.

Understanding Caribbean radio as a regional history—defined more by circuits and soundwaves than national borders—brings new dimensions to bear on radio histories more generally. Spanning the Caribbean allows me to think about how various listening publics came to be and the contingent nature of those publics. Imperial politics, machines—as instruments of curiosity, desire and violence—and voices converged and diverged in distinct ways to conjure particular publics in particular moments. In order to overcome disturbing origins, radio needed to take part in pre-existing publics. In Jamaica, the inclusion of programs in patois resuscitated a feeble medium. The voices of people like Louise Bennett rendered radio a welcome attraction rather than a patronizing nuisance. In Haiti, radio publics also grew as Kreyol radio plays replaced US-sanctioned programming. Francois Duvalier understood that he could use radio to appeal to many people, drawing them in with celebrations of Haiti’s African roots and Kreyol language. When he became dictator soon after, the publics were already captive. On the other hand, Cuba did not have such a stark linguistic divide. So as soon as radio blanketed the country it could take part in fuelling political rifts. Listening in Cuba meant choosing sides, as all sides spoke through the radio. As the oppositional 1950s turned into the revolutionary 60’s, the battle of voices—the Voice of America, the Voice of Martí, the Voice of Fidel, continued. Understanding the region as a transfer point for empire and capital places the Caribbean at the center of many aspects of the history of communications technologies. It also colors that history with troubling tones whose listeners are long overdue.

—

Alejandra Bronfman is Associate Professor of History at the University of British Columbia, where she teaches courses on Caribbean and Latin American history, historical theory and practice, race in the Americas, and media histories. She is currently working on two projects: A Voice in a Box: Media, Empire and Affiliation in the Caribbean, which records the unwritten histories of sonic technologies in the early twentieth century, and Biography of a Sonic Archive, which draws from the extensive career of Laura Boulton to interrogate the use of recordings in the making of a sonic, exotic Caribbean. http://alejandrabronfman.wordpress.com/

—

Featured image: “Cuba 1619 – 10th Anniversary of Radio Havana Cuba” by Flickr user Joseph Morris, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Decolonizing the Radio: Africa Abroad in the Age of Independence– Samantha Pinto

“Everyone I listen to, fake patois…”– Osvaldo Oyola

Hello, Americans: Orson Welles, Latin America, and the Sounds of the “Good Neighbor”– Tom McEnaney

13 responses to “Radio de Acción: Violent Circuits, Contentious Voices: Caribbean Radio Histories”

Trackbacks / Pingbacks

- - May 3, 2021

- - April 19, 2021

- - April 5, 2021

- - January 27, 2020

- - August 19, 2019

- - September 17, 2015

- - March 9, 2015

- - February 19, 2015

- - May 8, 2014

- - April 10, 2014

- - March 21, 2014

- - March 21, 2014

Fascinating! This makes me curious about if and how one might read ZunZuneo, USAID’s so-called”Cuban Twitter,” within the context of the histories and politics of communication technologies, such as radio, in Cuba. If any of these discussions are happening, I would love to know more.

LikeLike