From Mercury to Mars: Vox Orson

The problem of the voice has been at the center of sound studies for generations, but seldom has the knot of aesthetic and philosophical concerns — of vocal mechanics, of ontology, of desire — that “the voice” raises been brought to bear on a particular voice. As a result, ironically, a terrain deeply fascinated by materiality is often approached through abstraction. To amend this problem, what better case study could there be than Orson Welles, whose voice was without question one of the signature dramatic instruments of the twentieth century, and today retains a compelling power to instruct, to hypnotize and beguile.

The problem of the voice has been at the center of sound studies for generations, but seldom has the knot of aesthetic and philosophical concerns — of vocal mechanics, of ontology, of desire — that “the voice” raises been brought to bear on a particular voice. As a result, ironically, a terrain deeply fascinated by materiality is often approached through abstraction. To amend this problem, what better case study could there be than Orson Welles, whose voice was without question one of the signature dramatic instruments of the twentieth century, and today retains a compelling power to instruct, to hypnotize and beguile.

As SO!’s last full installment in From Mercury to Mars, a six-month series commemorating the radio work of Orson Welles we’re doing with Antenna, we are honored to present one of the most insightful writers on cinema, Murray Pomerance of Ryerson University, who has prepared a special essay focusing on the question of Welles’ voice. Writer and editor of more than a dozen books, Pomerance’s own voice has been crucial in how contemporary scholars, critics and fans have thought about the cinema for decades, and we’re elated to have him help us to wrap up the series.

What you’re about to read, ladies and gentlemen (a little razzle-dazzle, why not?), is something never attempted before, to my knowledge: a study of Orson Welles’s voice itself — not what it does, how it was used, or what it “represents,” exactly — but a study that tries to get at what Pomerance calls “that instrumentation [Welles] cannot prevent himself from employing except by silence.”

It’s the voice that sticks to every thought about Welles, the voice through which everything else in his radio work passes, and ultimately the voice that continues to outlast him.

nv

—

“I know that the thing I do best in the world is talk to audiences.”

Orson Welles to Bill Krohn (“My Favorite Mask is Myself: An Interview with Orson Welles,” The Unknown Orson Welles 70).

Most radio listeners across America knew the voice of George Orson Welles, a voice particularly adept for broadcasting, before they saw what he looked like. Even when he appeared, staring wrinkle-browed and wide-eyed from page 20 of the Los Angeles Times the day after “War of the Worlds” or hiding under the thick eyebrows and beard of Capt. Shotover from George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House, as framed by Paul Dorsey for the cover of Time May 9, 1938, they had to “fit” the picture to the sound (that is, one or more of his many sounds). The tall, doughy body generally produced a soft baritone—“I think it would be fun to run a newspaper”; “tomorrow is . . . forever”—worn at the edges like an heirloom tablecloth, thick as bisque, or evanescent as an Irish field seen distantly in foggy light.

His sound was just slightly adenoidal, but burnished, like eighteenth-century mahogany furniture. Listening to Welles, indeed, one felt raised to a cultural height, where the light could gleam more purely and satisfyingly than elsewhere. His enunciation was crisp and precise, never failing. David Thomson types his voice as “word-carving” (Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles 239). He breathed through, rather than around, his speech so that phrases would rise and fall with the body’s natural, “automatic” move to futurity; breathed with an overt will to reach the end of the phrase, of the sentence, of the story. In this he made talk the stuff of life. He was fond of long breaths and wordy deliveries, letting his stresses fall on vowels more often than not, as in singing Schubert. While as a performer he could produce any vocal gesture—hilarity, mockery, snideness, bitterness, pomposity—these clothed rather than inhabiting the voice, which was always, inevitably, excruciatingly, heart-rendingly clear and blunt. He had the ability to persuade us that what he said came from his heart, rather than a performer’s toolkit.

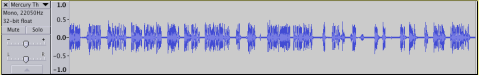

A visual rendering of Orson Welles’s voice (and pauses for breath) in the “Am I Richard Pierson” monologue from “War of the Worlds.”

Even the great John Barrymore, whose voice was an orchestra—the Barrymore whom Welles called “a golden boy, a tragic clown grimacing in the darkness, gritting his teeth against the horror” and who at the opening of Citizen Kane told a radio announcer that Orson was the bastard son of Ethel [Barrymore] and the Pope (Welles and Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles 24)– did not unfailingly invoke such sincerity. So it came to be, later in Welles’s life, that when on a talk show he told his host a story or gave her a lecture—cigar in hand he informed Dinah Shore in 1979 that her audience was not an audience, for example, because they had not paid to be there–one came to believe every syllable; and when he made F for Fake he counted on this vocal credibility, this urgently private and confessional key, to convey convincingly what had only been fabricated to convince. The convincing could be potent, and at the supremest level: Richard Wilson reports that it was after hearing “records of the Mercury’s radio production of The Magnificent Ambersons” (not, note, after reading a scenario) that George Schaefer, President of RKO, “gave Orson the okay for that film” (“It’s Not Quite All True,” Sight & Sound, Spring 1970, 191).

If it is one thing to discourse upon how the voice is structured into a performance, a broadcast, a staging, invoking, to take a case, shunting, audiopositioning, overdubbing, personalizing (see Verma, Theater of the Mind 140; 35-45; 185), it is quite another to stand before, to confront, the voice. In one case we wonder what can happen to the voice, in the other we ask of the voice what it is. Orson Welles’s voice, not what he says, not what he means, not who he is pretending to be, but that instrumentation he cannot prevent himself from employing except by silence . . .? What is the voice which one takes for granted in quoting his dialogue, as though what he says were equivalent to his saying it? And given that Welles is now silent, can the reader who never heard him be brought to a sympathetic understanding through any form of argument or description? Youtubing him for the first time, what does one hear, that Welles repeatedly brought forward through the frame of his instrumentality and the agony of his breath? An urgent desire to be heard, certainly. Listen to this, listen to me, listen harder. Spitting words, or giggling like a little child.

Language as we speak it need pay no fealty to the speaker’s attitude toward—feeling about—what he says; the words have the power to contain both meaning and feeling, but it is not a requirement that they be enunciated, emphatically shifted, or turned to self-consciousness in the event that the speaker finds them, apt, silly, or simple. The voice is beyond the words. It is something for which we can have a taste. Taste “cannot be rendered by anything other than itself,” suggests Leroi-Gourhan, it is a “[part] of our sensory apparatus [that] must always remain infra-symbolic” (Gesture and Speech 281). Thus, the trick about voicing text for microphone is to pronounce, not utter. One must put some faith that English will hold meaning without the addition of the voice; so that—as regards meaning–in voicing one expresses a humble self-deprecation in the face of something greater than oneself.

Vienna’s Riesenrad, where Orson Welles gave a famous speech as Harry Lime in The Third Man. Photo from Wikimedia Commons, 2004.

Welles’s voice is filled to the brim with this humility, this self-deprecation, this ease, this insouciant presence. The words sound out, no matter their shape. And so: “The cuckoo clock!” as a punch line in that lengthy, magnificent speech of Harry Lime’s in the Viennese Ferris wheel in The Third Man. “KOO-koo.” With Welles’s great dignity (massive girth) and profound experience, this kindergarten word gives him over to self-mockery, disidentification; but Harry Lime just says it, with a little elevation of tone for comic punch, and a lifted eyebrow, since the cuckoo clock is a most unexpected answer to the question of what the Swiss can claim to have produced after five hundred years of peace.

Is it necessary if one is hearing the actor’s voice to consider his every line of dialogue? What he says is so unimportant next to the fact that he is saying it. In F for Fake (1973) he gives us Elmyr de Hory’s recipe for an omelette: “Steal two eggs”: but that first word is pronounced at length, shall we say “Hungarian style”? “Steeeeeal two eggs,” and with a growl, a feline growl. The speaker approves, thinks it hilarious, this recipe, but is also dutiful in trying to capture the way Elmyr, the Hungarian art forger, speaks, and thus thinks. Speaking is thinking. That’s “El-meeeer.” In voweling as he does, that is to say, reveling in the vowels, stressing them, privileging them as golden roots of speech, Welles makes a voice that is theatrically expansive, the raconteur’s exaggerations of effect and fact embedded in exaggerations of fundamental sounds. Peter Von Bagh: “Welles is the last important raconteur of tales” (“Some Minor Keys to Orson Welles,” The Unknown Orson Welles 5). The vowels open us, open our receptivity and tap our wellspring of sensibility. They are not technical, not bitten or chewed, not tongued against the palate, in brief, not tooled and machined through the body’s hard flesh but instead summoned in and thrown from the body as organ. “El-meeer”: all a kind of pretense, this apparently being Hungarian, this embedding Elmyr inside the voice, as any good raconteur will do with his prize character.

Joseph McBride becomes rapturous about a scene in the film outside the Chartres cathedral, in which, as he puts it, Welles speaks in his own voice, “dropping all pretense and facetiousness to deliver a magnificent soliloquy on the transcendent reality of art” (Orson Welles 189). Careful, I think: the form of the soliloquy instantly downgrades all enunciation into sincerity. We may think of Welles’s tendency to deliver every speech as though it were a soliloquy — to tell us, as Simon Callow notes the announcer taught on The Campbell Playhouse, “a great human story, welling up from the heart, brimming with deep and sincere emotion” (Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu 419)—and the “magnificence” of the dialogue, carefully written to seem “magnificent,” augments our tendency to adore the voice that speaks it. Yet we do adore that voice, and adoration is part of the cinematic effect. As to whether this is Welles’s own voice: I never met him.

Or can we think for just a moment of the singsong most frequently attributed to Welles, vitiated, almost dead: the word “Rosebud” in Citizen Kane. Ohhh–uh. Not “Rrrose-bbuddd” but “Rohhhhhz-buhd.” Billy Budd. Billy Rose. We can hear Joe Cotten (Jedediah Leland) say it, harsh, grating, perfunctory, pushing the “b”; and Everett Sloane (Mr. Bernstein), with emphasis on the “s”: “rose-bud.” A day hasn’t gone by he doesn’t remember that girl, but what’s Rosebud? Paul Stewart (Raymond)? Everything a question out of his mouth, even the time of day. Life a question, relations a question, existence a question. “Rosebud?” he hardly gives a breath to say it.

But Welles breathes it, with an expulsion of air that seems thick with embodiment: gigantic air, fulsome air, the air of the past lasting on through a winter memory preserved under glass. Again: not the meaning of the word, its tinny echo, what it connotes, how it is grammatically constructed, but what people feel when they say. It is certainly not—anticlimax of anticlimaxes—the thing itself, whose name Rosebud is. Inside Welles, in his organ of speech, in the interior of interiors, Rosebud is a future waiting to emerge. “With youthful exuberance, Welles was after a special space concept of his own,” writes Von Bagh, “a very personal dramaturgical form, a kind of relief of sound space which then, in the miraculous turn of Citizen Kane, was elevated into a kind of relief or multi-dimension of visual space” (5).

A certain delicious theatricality flavors much of what we hear from Welles, the sort of tone that caused Ernest Hemingway, as legend has it, to berate him for the “too flowery” delivery of narration in Joris Iven’s The Spanish Earth (1937) and inspire the slur that he was nothing but a “‘faggot’ from the New York theater” (McBride 204). Welles, of course, put up his dukes. But while I don’t think Orson Welles’s voice is ever flowery, it often floats up onto an imaginary British promontory, especially, in certain precise dramatic circumstances, with the effete (but feigned) pronunciation of the “high R.” (“High” as in Upper.) September 9, 1936 for the Columbia Broadcasting System, playing Hamlet: “‘Tis an unweeded garden/ That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature/ Possess it merely (I.ii.339-41): on the East Coast we would say GARR-dn, with the “r” emerging from a mouth where the tongue is lifted back (and possibly also the lower lip), but Welles gives us “GAH-dn” with the lazy tongue staying put:

Lazy: there is very frequently a sense of his lazy mouth, as though everything he says is obvious, yet he takes pleasure in the words dribbling in their channel through his mouth. His is not the striven-for, aggressive, punchy, muscular articulation of Jimmy Stewart. “An unweeded gahh-dn,” and it is possessed “meehh-ly.” To actually say the r is to try too hard, so there is something aristocratic, perhaps condescending about the style. Was it this provoked Hemingway so much? Welles’s Jean Valjean in his 1937 “Les Miserables” doesn’t talk this way at all, shows it as affectation. His is a deeper vocality— André Bazin suggests that Orson was encouraged, young, to make his voice “prematurely deep” (Orson Welles 5)—and is charged with his own masculine version of Californian vocal fry, thus seeming not only distinctively eroded, ruined, portentous, and artfully combative (in a way that we can hear as well in his insert into Manowar’s “Dark Avenger” track), but elevated in social status as well (see Ikuko Yuasa “Creaky Voice: A New Feminine Voice Quality for Young Urban-Oriented Upwardly Mobile American Women?,” American Speech 85: 3, 317). The voice of a prophet who has talked too much (perhaps to no avail).

By the middle of 1938 on “The Shadow,” Welles’s Lamont is climbing again, intoning like a bassoon but persisting in naming a ship the “Stahhh of Zealand” in an episode entitled “The Power of the Mind.” When you wish upon a “stahhhh,” you are high enough to be above wishing. Anglicism here, too, in the soft “u” sound of “news”: “The Shipping Nyews.” And hints of a “freighter” carrying “general cahhh-go.”

Dropping down to the common level again December 9, 1938 for “Rebecca” with Margaret Sullavan, but only for a fragmentary moment—“Yer not afraid of the fyew-chuh?”—before another ascension, “You’re cheap at ninety pounds a yee-ahhhh,” or “An empty house can be as lonely as a full hotel, the trouble is that it’s less impehhh—sonal.” Then when the play is done he tells his eager, and by now intimately proximate, listeners that the “STAR of ‘Rebecca’ is standing “beside me at the microphone”: “staRR,” and “mike-Ro-phone.”

In “The Hitchhiker,” September 2, 1942, he mentions a “licence number”: “num-beRR.” But for “The 39 Steps” on The Mercury Theater, August 1, 1938, he had gone for a breathy and plummy emphasis on vowels: “In the blue evening sky, I saw something . . .” spoken as “In the BLOO eeevning SKAH-eee.”

If it was true, as Charlton Heston reported, that “Orson has a marvelous ear for the way people talk” (James Delson “Heston on Welles: An Interview,” Focus on Orson Welles 62), he both relied and did not rely upon that ear, bringing out of himself a sound that was now from a street corner, now from a temple, now from an impossibly high aerie where experience is pure. That voice carried more in the imagination than in the atmosphere, and perhaps this is why it echoes so unendingly inside his listener’s desire.

* with thanks to Tom Dorey, Jeffrey Dvorkin, Bill Krohn, Sarah Milroy, Neil Verma

__

From Mercury to Mars is a joint six-month venture between Sounding Out! and Antenna at the University of Wisconsin. The fifteenth and final post, by radio historian Jennifer Hyland Wang, is coming on Antenna in a few weeks.

To catch up on the series, check out our preceding posts.

- Here is “Hello Americans,” Tom McEnaney‘s post on Welles and Latin America

- Here is Eleanor Patterson‘s post on editions of WOTW as “Residual Radio”

- Here is “Sound Bites,” Debra Rae Cohen‘s post on Welles’s “Dracula”

- Here is Cynthia B. Meyers on the pleasures and challenges of teaching WOTW in the classroom

- Here is Kathleen Battles on parodies of Welles by Fred Allen

- Here is Shawn VanCour on the second act of War of the Worlds

- Here is the navigator page for our #WOTW75 collective listening project

- Here is Josh Shepperd’s post, “War of the Worlds and the Invasion of Media Studies”

- Here is Aaron Trammell‘s remarkable mix of the thoughts of more than a dozen radio scholars on “War of the Worlds.”

- Here is our podcast of Monteith McCollum‘s amazing WOTW remix

- Here is “Devil’s Symphony,” Jacob Smith‘s study of the “eco-sonic” Welles.

- Here is Michele Hilmes‘s post on the persistence and evolution of radio drama overseas after Welles.

- Here is A Brad Schwartz on Welles’s adaptations of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Trackbacks / Pingbacks