X! : Blog-O-Versary 10.0

** Click here to head straight to our free, downloadable X! 10.0 Blog-O-Versary Mix! It’s okay, like Tupac, we ain’t mad at ya! It’s cool to come back here though and check this out. **

We didn’t have a clue where the blog was headed when we started out in 2009, packed into AT’s humid apartment on Seminary in Binghamton, alternately helping him pack, looking through his records, and making plans for this writing thing we were going to do together to stay in touch. I had a newborn baby strapped on my chest, Aaron was leaving BU to start a PhD program at Rutgers and Liana was embarking deeply into her dissertation (and just a year later for Kansas City. . .for the full origin story, catch our recent co-authored piece “The Pleasure [is] Principle: Sounding Out! and the Digitization of Community” in Digital Sound Studies). Our tight-knit research crew was facing so much change and uncertainty, that I’m pretty sure we decided to name the blog Sounding Out! as a form of echolocation. If talking and thinking about sound waves had brought us together in the first place, perhaps their resonance could stretch out to fill the unknown contours of the future that lay ahead.

And over the past decade, it has. Not just for us as friends, co-workers, and eventually shared hive-mind cells, but for the field of sound studies, which in the same decade went from “huh?” to “emerging,” then from academic hipster cred and to everybody’s tryna put “soundscape” in everything, to the New York Times magazine does a cover story on it AND you can now get a Masters in it at Northwestern University in Chicago [shout out to SO! special editor Neil Verma, who not only edited a media stream for us from 2013-2016 but—among many other awesome things—helped get this very program up and running]. It’s no coincidence that the field’s trajectory and reach has grown exponentially along with ours, and we are proud as hell of that.

Other things we are most proud of:

- that, on separate occasions in the past year, two brilliant people have told us that reading SO! inspired them to go to grad school because our site hosted and valued research on sound by/about women of color (these stories are literally our favorite 😭 😭 😭 and inspire us to go even harder!).

- growing deep, connected relationships among scholars and professionals in the field infused with fun and feeling amongst the brilliance and rigor.

- surpassing one MILLION unique clicks (not that “metrics” has ever been our goal but holla!!).

- getting on the podcast tip early (2010!!) and staying weird as hell with it (free format por vida!).

- always being down to shout out and collabo (over the years we’ve worked with Antenna, Locatora Radio, The Radio Preservation Task Force, IASPM-US, Soundbox, The Middle Spaces, Tuned City Brussels, WHRW 90.5, Everything Sounds, Not Your Muse, and The UC Riverside Punk Con, among many others. In 2020 we have something going with the Zora Neale Hurston festival in Eatonville, Florida. . . stay tuned!).

- publishing a post on “Old Town Road.” IJS. Our regular writers always bring it. Thank you to Justin Burton and Robin James, our current roster, and to all of our past fam: Regina Bradley, Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo, Maile Colbert, Osvaldo Oyola, and Andreas Pape.

- pushing so hard for our reach, readership, and coverage to become increasingly global (in the past year we hosted pieces from and/or about Argentina, Australia, Canada, China, Cuba, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, and Ukraine).

- developing a strong undergraduate internship program through Binghamton University that brings us literally the best interns in the WORLD 💯. They bring us new ideas, excitement, and new social media accounts, and we entrust them with everything we know about editing and digital publishing. It’s been a blast, and we are so proud they’ve all gone on to do wonderful work in the world.

- that our roster of writers more accurately represents the diversity of sound studies scholars than any other publication out there by leaps and bounds.

- that SO! has continued to evolve in interesting ways while strengthening and refining our guiding mission over the years: to find, nurture, and share accessible top-notch scholarship/art/thought that investigates how power impacts how we sound and listen, while amplifying sound studies knowledge toward social justice.

- AND MOST IMPORTANTLY, that so many readers have put their faith in us and so many amazing writers have thought of us as a home for their work. We take your trust so very seriously, and remain humbled by your generosity and confidence. Thank you, thank you, THANK YOU for being Sounding Out! along with us.

I’m trying to keep it short and cute today, not saying too TOO much because this post [our 624th!] is neither a retrospective nor a tribute, but a celebration. . .as Diddy once said, we ain’t going nowhere! [Editors’ Note: Other notables JS has referenced in the previous decade of Blog-o-Versary posts includes Bob Marley, LL Cool J, De La Soul, Schoolhouse Rock, Dionne Warwick, the Solid Gold Dancers, S.E. Hinton, Beyoncé, Langston Hughes, X-Ray Spex, A Tribe Called Quest, Fred Moten, Bill Withers, and . . . Taylor Swift. Oof.]. And bet, we have AMAZING things planned for next year, including forums on Soundwalking while POC (starts next week!), the 50th anniversary of Charles Mingus’s Ah Um (guest edited by Earl Brooks), audiobooks (edited by Liana Silva), and sound and climate change (guest edited by Anja Kanngieser), an undergraduate sound studies showcase, and . . . . . . . . . .

[🥁🥁🥁🥁🥁🥁🥁]

we just finished a book proposal for a Sounding Out! anthology: working title Power in Listening: The Sounding Out! Reader.

[🎉 insert airhorn sound here 🎉]

YES! We couldn’t be more grateful for the last ten years, and we couldn’t be more excited for what’s coming up next. Even though we didn’t know where we were headed in 2009, we have arrived nonetheless, and all because we knew what we wanted—to create a community just like this one. Happy X! Blog-o-Versary to all of us, today!

–JLS, LMS, and AT

XXXXXXXXXX Highlight Reel XXXXXXXXXX

- Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo successfully defended her dissertation, and had the chance to open for Bikini Kill in June, under her stage name Sammus. In fall of 2019 she will be starting a two-year postdoc at Brown University’s music department, and will be getting married to fiction writer Lance Akinsiku. She is presenting a Making/Doing session at this year’s 4S Conference in New Orleans in September.

- John Melillo has a new essay on the French sound poet Henri Chopin in Ties: Journal of Text, Image, and Sound. His book, The Poetics of Noise, is under contract for Bloomsbury’s Sound Studies list.

- In summer 2018 Kristin Moriah began a position as an Assistant Professor of African American Literary Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. “Where Are the Black Angels?” her review of Mickalene Thomas’s historic exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario is forthcoming in PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 123, as is “A Greater Compass of Voice: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Black Performance in Nineteenth-Century North America,” which will be published in Theatre Research in Canada. She is excited to attend the ASA annual meeting in Honolulu where she will present “Playing the Red Record: Black Feminist Recording Practices.”

- Phillip Sinitiere published several pieces on W. E. B. Du Bois in The North Star. He also co-organized a forum on Shirley Graham Du Bois at Black Perspectives. He is the 2019-2020 W. E. B. Du Bois Visiting Scholar at UMass Amherst.

- SO! Ed-in Chief Jennifer Lynn Stoever published three essays in 2018/19: “‘Doing fifty-five in a fifty-four’: Cop Voice, U.S. Policing and the Cadence of White Supremacy” (Interdisciplinary Journal of Voice Studies), “Black Radio Listeners in America’s ‘Golden Age'” (Journal of Radio and Media Studies), and “Crate Digging Begins at Home: Black and Latinx Women Collecting and Selecting Records in the 1960s and ‘70s Bronx” in the Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Studies, which you can download for free here.

And remember, the “notes” on our Facebook page is *still the best place to hear about calls for art, calls for posts, and upcoming conferences, shows, and volumes in sound studies. “Like” us here and please continue to keep us in the loop regarding new projects. We love to signal boost, as you can probably tell by our very active Twitter feed!

Clic here for Sounding Out!‘s Blog-O-Versary “X!” mix 10.0 with track listing (and of course which writers suggested which songs)!

—

Jennifer Lynn Stoever is co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Sounding Out! She is also Associate Professor of English at Binghamton University, lead organizer of The Binghamton Historical Soundwalk Project and author of The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening (NYU Press, 2016).

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2018 “Sound the Alarm” mix 9.0

- 2017 “!!!!Resist!!!!” Blog-O-Versary mix 8.0

- 2016 Blog-O-Versary “!!!!!!!” mix 7.0

- 2015 Blog-o-Versary 6.0 Keep on Pushing! (Our 400th post!!)

- 2014 #flawless 5.0 celebration and mix

- 2013 Blog-o-Versary 4.0: Solid Gold Summer Countdown!

- 2012 #Blog-O-Versary 3.0: Can’t Stop Won’t Stop (The Awesomeness)!

- 2011 “Awesome Sounds from a Future Boombox” 2.0

- 2010 First Blog-O-Versary party mix: A Celebration of Awesomeness

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2018!

For your end-of-the year reading pleasure, here are the Top Ten Posts of 2018 (according to views as of 12/4/18). Visit this brilliance today–and often!–and know more fire is coming in 2019!

***

J. Martin Vest

In the early 1870s a talking machine, contrived by the aptly-named Joseph Faber appeared before audiences in the United States. Dubbed the “talking head” by its inventor, it did not merely record the spoken word and then reproduce it, but actually synthesized speech mechanically. It featured a fantastically complex pneumatic system in which air was pushed by a bellows through a replica of the human speech apparatus, which included a mouth cavity, tongue, palate, jaw and cheeks. To control the machine’s articulation, all of these components were hooked up to a keyboard with seventeen keys— sixteen for various phonemes and one to control the Euphonia’s artificial glottis. Interestingly, the machine’s handler had taken one more step in readying it for the stage, affixing to its front a mannequin. Its audiences in the 1870s found themselves in front of a machine disguised to look like a white European woman.[. . .Click here to read more!]

9).Mixtapes v. Playlists: Medium, Message, Materiality

Mike Glennon

The term mixtape most commonly refers to homemade cassette compilations of music created by individuals for their own listening pleasure or that of friends and loved ones. The practice which rose to widespread prominence in the 1980s often has deeply personal connotations and is frequently associated with attempts to woo a prospective partner (romantic or otherwise). As Dean Wareham, of the band Galaxie 500 states, in Thurston Moore’s Mix-Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture, “it takes time and effort to put a mix tape together. The time spent implies an emotional connection with the recipient. It might be a desire to go to bed, or to share ideas. The message of the tape might be: I love you. I think about you all the time. Listen to how I feel about you” (28).

Alongside this ‘private’ history of the mixtape there exists a more public manifestation of the form where artists, most prominently within hip-hop, have utilised the mixtape format to the extent that it becomes a genre, akin to but distinct from the LP. As Andrew “Fig” Figueroa has previously noted here in SO!, the mixtape has remained a constant component of Hip Hop culture, frequently constituting, “a rapper’s first attempt to show the world their skills and who they are, more often than not, performing original lyrics over sampled/borrowed instrumentals that complement their style and vision.” From the early mixtapes of DJs such as Grandmaster Flash in the late ’70s and early ’80s, to those of DJ Screw in the ’90s and contemporary artists such as Kendrick Lamar, the hip-hop mixtape has morphed across media, from cassette to CDR to digital, but has remained a platform via which the sound and message of artists are recorded, copied, distributed and disseminated independent of the networks and mechanics of the music and entertainment industries. In this context mixtapes offer, as Paul Hegarty states in his essay, The Hallucinatory Life of Tapes (2007), “a way around the culture industry, a re-appropriation of the means of production.” [. . .Click here for more!]

8).My Music and My Message is Powerful: It Shouldn’t be Florence Price or “Nothing”

Samantha Ege

Flashback to the second day of the recent Gender Diversity in Music Making Conference in Melbourne, Australia (6-8 July 2018). In a few hours, I will perform the first movement of the Sonata in E minor for piano by Florence Price(1887–1953). In the lead-up, I wonder whether Price’s music has ever been performed in Australia before, and feel honored to bring her voice to new audiences. I am immersed in the loop of my pre-performance mantra:

My music and message is powerful, my music and message is powerful.

Repeating this phrase helps me to center my purpose on amplifying the voice of a practitioner who, despite being the first African-American woman composer to achieve national and international success, faced discrimination throughout her life, and even posthumously in the recognition of her legacy.

In Price’s time, there were those in positions of privilege and power who listened to her music and gave her a platform. One such instance was Frederick Stock of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and his 1933 premier of her Symphony in E minor. But there were times when her musical scores were met with silence. For example, when she wrote to Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony Orchestra requesting that he hear her music, the letter remained unanswered. There was a notable intermittency in how Price was heard, which continues today. It seems most natural for mainstream platforms to amplify her voice in months dedicated to women and Black history; any other time of the year appears to require more justification. And so, as I am repeating this mantra—my music and message is powerful—I am attempting to de-centre my anxieties, and center my service to amplifying Price’s voice through an assured performance . [. . .Click here for more!]

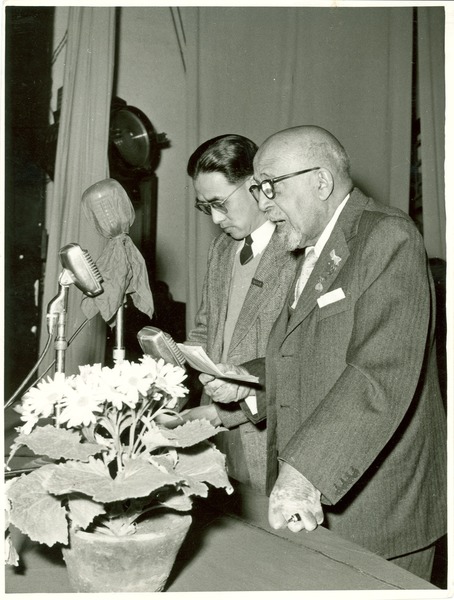

7). “Most pleasant to the ear”: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Itinerant Intellectual Soundscapes

Phillip Sinitiere

Upon completing a Ph.D. in history at Harvard in 1895, and thereafter working as a professor, author, and activist for the duration of his career until his death in 1963, Du Bois spent several months each year on lecture trips across the United States. As biographers and Du Bois scholars such as Nahum Chandler, David Levering Lewis, and Shawn Leigh Alexander document, international excursions to Japan in the 1930s included public speeches. Du Bois also lectured in China during a global tour he took in the late 1950s.

In his biographical writings, Lewis describes the “clipped tones” of Du Bois’s voice and the “clipped diction” in which he communicated, references to the accent acquired from his New England upbringing in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Reporter Cedric Belfrage, editor of the National Guardian for which Du Bois wrote between the 1940s and 1960s, listened to the black scholar speak at numerous Guardian fundraisers. “On each occasion he said just what needed saying, without equivocation and with extraordinary eloquence,” Belfrage described. “The timbre of his public-address voice was as thrilling in its way as that of Robeson’s singing voice. He wrote and spoke like an Old Testament prophet.” George B. Murphy heard Du Bois speak when he was a high school student and later as a reporter in the 1950s; he recalled the “crisp, precise English of [Du Bois’s] finely modulated voice.” [. . .Click here for more]

6.) Beyond the Grave: The “Dies Irae” in Video Game Music

Karen Cook

For those familiar with modern media, there are a number of short musical phrases that immediately trigger a particular emotional response. Think, for example, of the two-note theme that denotes the shark in Jaws, and see if you become just a little more tense or nervous. So too with the stabbing shriek of the violins from Psycho, or even the whirling four-note theme from The Twilight Zone. In each of these cases, the musical theme is short, memorable, and unalterably linked to one specific feeling: fear.

The first few notes of the “Dies Irae” chant, perhaps as recognizable as any of the other themes I mentioned already, are often used to provoke that same emotion. [. . .Click here for more!]

5). Look Away and Listen: The Audiovisual Litany in Philosophy

Robin James

According to sound studies scholar Jonathan Sterne in The Audible Past, many philosophers practice an “audiovisual litany,” which is a conceptual gesture that favorably opposes sound and sonic phenomena to a supposedly occularcentric status quo. He states, “the audiovisual litany…idealizes hearing (and, by extension, speech) as manifesting a kind of pure interiority. It alternately denigrates and elevates vision: as a fallen sense, vision takes us out of the world. But it also bathes us in the clear light of reason” (15). In other words, Western culture is occularcentric, but the gaze is bad, so luckily sound and listening fix all that’s bad about it. It can seem like the audiovisual litany is everywhere these days: from Adriana Cavarero’s politics of vocal resonance, to Karen Barad’s diffraction, to, well, a ton of Deleuze-inspired scholarship from thinkers as diverse as Elizabeth Grosz and Steve Goodman, philosophers use some variation on the idea of acoustic resonance (as in, oscillatory patterns of variable pressure that interact via phase relationships) to mark their departure from European philosophy’s traditional models of abstraction, which are visual and verbal, and to overcome the skeptical melancholy that results from them. The field of philosophy seems to argue that we need to replace traditional models of philosophical abstraction, which are usually based on words or images, with sound-based models, but this argument reproduces hegemonic ideas about sight and sound. [. . .Click here to read more!]

4). becoming a sound artist: analytic and creative perspectives

Rajna Swaminathan

Recently, in a Harvard graduate seminar with visiting composer-scholar George Lewis, the eminent professor asked me pointedly if I considered myself a “sound artist.” Finding myself put on the spot in a room mostly populated with white male colleagues who were New Music composers, I paused and wondered whether I had the right to identify that way. Despite having exploded many conventions through my precarious membership in New York’s improvised/creative music scene, and through my shift from identifying as a “mrudangam artist” to calling myself an “improviser,” and even, begrudgingly, a “composer” — somehow “sound artist” seemed a bit far-fetched. As I sat in the seminar, buckling under the pressure of how my colleagues probably defined sound art, Prof. Lewis gently urged me to ask: How would it change things if I did call myself a sound artist? Rather than imposing the limitations of sound art as a genre, he was inviting me to reframe my existing aesthetic intentions, assumptions, and practices by focusing on sound.

Sound art and its offshoots have their own unspoken codes and politics of membership, which is partly what Prof. Lewis was trying to expose in that teaching moment. However, for now I’ll leave aside these pragmatic obstacles — while remaining keenly aware that the question of who gets to be a sound artist is not too distant from the question of who gets to be an artist, and what counts as art. For my own analytic and creative curiosity, I would like to strip sound art down to its fundamentals: an offering of resonance or vibration, in the context of a community that might find something familiar, of aesthetic value, or socially cohesive, in the gestures and sonorities presented. [. . .Click here for more!]

Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr.

How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House? –DJ Irene

At the Arena Nightclub in Hollywood, California, the sounds of DJ Irene could be heard on any given Friday in the 1990s. Arena, a 4000-foot former ice factory, was a haven for club kids, ravers, rebels, kids from LA exurbs, youth of color, and drag queens throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The now-defunct nightclub was one of my hang outs when I was coming of age. Like other Latinx youth who came into their own at Arena, I remember fondly the fashion, the music, the drama, and the freedom. It was a home away from home. Many of us were underage, and this was one of the only clubs that would let us in.

Arena was a cacophony of sounds that were part of the multi-sensorial experience of going to the club. There would be deep house or hip-hop music blasting from the cars in the parking lot, and then, once inside: the stomping of feet, the sirens, the whistles, the Arena clap—when dancers would clap fast and in unison—and of course the remixes and the shout outs and laughter of DJ Irene, particularly her trademark call and response: “How Many Motherfucking Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?,” immortalized now on CDs and You-Tube videos.

Irene M. Gutierrez, famously known as DJ Irene, is one of the most successful queer Latina DJs and she was a staple at Arena. Growing up in Montebello, a city in the southeast region of LA county, Irene overcame a difficult childhood, homelessness, and addiction to break through a male-dominated industry and become an award-winning, internationally-known DJ. A single mother who started her career at Circus and then Arena, Irene was named as one of the “twenty greatest gay DJs of all time” by THUMP in 2014, along with Chicago house music godfather, Frankie Knuckles. Since her Arena days, DJ Irene has performed all over the world and has returned to school and received a master’s degree. In addition to continuing to DJ festivals and clubs, she is currently a music instructor at various colleges in Los Angeles. Speaking to her relevance, Nightclub&Bar music industry website reports, “her DJ and life dramas played out publicly on the dance floor and through her performing. This only made people love her more and helped her to see how she could give back by leading a positive life through music.” [. . .Click here for more!]

2). Canonization and the Color of Sound Studies

Budhaditya Chattopadhyay

Last December, a renowned sound scholar unexpectedly trolled one of my Facebook posts. In this post I shared a link to my recently published article “Beyond Matter: Object-disoriented Sound Art (2017)”, an original piece rereading of sound art history. With an undocumented charge, the scholar attacked me personally and made a public accusation that I have misinterpreted his work in a few citations. I have followed this much-admired scholar’s work, but I never met him personally. As I closely read and investigated the concerned citations, I found that the three minor occasions when I have cited his work neither aimed at misrepresenting his work (there was little chance), nor were they part of the primary argument and discourse I was developing.

What made him react so abruptly? I have enjoyed reading his work during my research and my way of dealing with him has been respectful, but why couldn’t he respect me in return? Why couldn’t he engage with me in a scholarly manner within the context of a conversation rather than making a thoughtless comment in public aiming to hurt my reputation?

Consider the social positioning. This scholar is a well-established white male senior academic, while I am a young and relatively unknown researcher with a non-white, non-European background, entering an arena of sound studies which is yet closely guarded by the Western, predominantly white, male academics. This social divide cannot be ignored in finding reasons for his outburst. I immediately sensed condescension and entitlement in his behavior. [. . .Click here for more!]

1). Botanical Rhythms: A Field Guide to Plant Music

Carlo Patrão

Only overhead the sweet nightingale

Ever sang more sweet as the day might fail,

And snatches of its Elysian chant

Were mixed with the dreams of the Sensitive Plant

Percy Shelley, The Sensitive Plant, 1820

ROOT: Sounds from the Invisible Plant

Plants are the most abundant life form visible to us. Despite their ubiquitous presence, most of the times we still fail to notice them. The botanists James Wandersee and Elizabeth Schussler call it “plant blindness, an extremely prevalent condition characterized by the inability to see or notice the plants in one’s immediate environment. Mathew Hall, author of Plants as Persons, argues that our neglect towards plant life is partly influenced by the drive in Western thought towards separation, exclusion, and hierarchy. Our bias towards animals, or zoochauvinism–in particular toward large mammals with forward facing eyes–has been shown to have negative implications on funding towards plant conservation. Plants are as threatened as mammals according to Kew’s global assessment of the status of plant life known to science. Curriculum reforms to increase plant representation and engaging students in active learning and contact with local flora are some of the suggested measures to counter our plant blindness.

Participatory art including plants might help dissipate plants’ invisibility. Some authors argue that meaningful experiences involving a multiplicity of senses can potentially engage emotional responses and concern towards plants life. In this article, I map out a brief history of the different musical and sound art practices that incorporate plants and discuss the ethics of plant life as a performative participant. [. . .Click here for more!]

—

Featured Image: “SO! stamp” by j. Stoever

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2017!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2016!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2015!

Blog-o-versary Podcast EPISODE 62: ¡¡¡¡RESIST!!!!

Recent Comments