My Music and My Message is Powerful: It Shouldn’t be Florence Price or “Nothing”

Flashback to the second day of the recent Gender Diversity in Music Making Conference in Melbourne, Australia (6-8 July 2018). In a few hours, I will perform the first movement of the Sonata in E minor for piano by Florence Price (1887–1953). In the lead-up, I wonder whether Price’s music has ever been performed in Australia before, and feel honored to bring her voice to new audiences. I am immersed in the loop of my pre-performance mantra:

My music and message is powerful, my music and message is powerful.

Repeating this phrase helps me to center my purpose on amplifying the voice of a practitioner who, despite being the first African-American woman composer to achieve national and international success, faced discrimination throughout her life, and even posthumously in the recognition of her legacy.

In Price’s time, there were those in positions of privilege and power who listened to her music and gave her a platform. One such instance was Frederick Stock of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and his 1933 premier of her Symphony in E minor. But there were times when her musical scores were met with silence. For example, when she wrote to Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony Orchestra requesting that he hear her music, the letter remained unanswered. There was a notable intermittency in how Price was heard, which continues today. It seems most natural for mainstream platforms to amplify her voice in months dedicated to women and Black history; any other time of the year appears to require more justification. And so, as I am repeating this mantra—my music and message is powerful—I am attempting to de-centre my anxieties, and center my service to amplifying Price’s voice through an assured performance.

I applied to the conference a few months ago. I was keen to bring my research to new audiences. Upon seeing that the conference was in Australia, I knew this would be a fantastic opportunity to gain transnational insight into the ongoing work around representation and inclusion in music. Fast-forward to July: here I am, in Australia for the first time. The venue is unfamiliar and I have not met anyone here before this visit. However, this is what I do know: I have fifteen minutes for my performance; hence, I have only prepared the first movement of the sonata. Looking in the program, I noticed there will be a paper taking place at the same time as my performance, given by an academic who identified himself in his printed abstract as “a white, old, straight man with power and privilege.”

The title of his paper? “I Have Nothing to Say.” While gender diversity was the overarching theme of the conference, the goal towards inclusion negated the fact that not all platforms are created equal. The speaker’s proposed topic advertised the ease with which the dominant voice may access a space for its mere presence, regardless of what will be said. Conference logistics then set this voice and its contribution against the radically diverse sounds of our time slot. In addition to my lecture and performance, there are several other events taking place simultaneously. The subjects include: mentoring women composers, creative realizations of parenthood in composition, gender balance in Australian jazz, interpretative approaches to the music of Kaija Saariaho, music as a vehicle for navigating the challenges around non-binary and transgender identity, and a cis-gendered white man’s exploration of ceding power and listening.

I remember a casual conversation the night before in which the joke arose of the speaker being “the token white man.” Of course it was a joke; the very notion is absolutely ridiculous. I remember reflecting on tokenization earlier that day and tweeting to that effect:

I knew the joke was light-hearted, but there is nothing light-hearted about being a token, nothing light-hearted about knowing your excellence, yet wondering if it will even factor into the decisions around your involvement. Anyway, I did not want to prioritize thoughts about the token white man over my purpose at the conference because that would take up time, space and energy, and in my pre-performance rituals, that time, space and energy belongs exclusively to the women that I seek to honour.

When it is time to perform, I bow, then sit, then sink into the first sound, which is this rich e minor chord that engages almost all of my fingers. I relish the rich tones in the grandeur of the introduction. But as the first theme comes in, conjuring up the soundworld of plantation songs, I calm the mood down to ensure that the lyricism of the top melody really sings.

My music and message is powerful.

The performance is followed by a presentation where I talk more about the sonata, who Price was, and what she achieved. I make sure to highlight her Arkansan roots and her Chicago successes, particularly around the Symphony in E minor. I speak about the influence of the spirituals within the classical frameworks of her compositions. I also speak about the privilege and the incredibly moving significance of being able to present and perform her music for an audience, largely of African descent, at the Chicago Symphony Center.

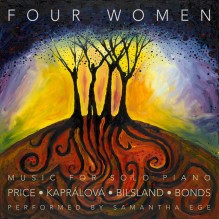

I play excerpts from the rest of the sonata off my recent album Four Women on Spotify and struggle to find the best time to pause the track because there is so much that I want the audience to hear: from the development of spiritual themes in the second movement, to the virtuosic whirlwind that is the final movement.

A dynamic discussion ensues, weaving in the narratives of Nina Simone, African-American folk tradition and my passion for this repertoire. I elaborate upon the ways in which exploring classical music by women has been an empowering personal journey. I articulate how the perception of men achieving “firsts” renders them gods while women achieving “firsts” are miracles that were never supposed to happen, that may never happen again. I express my role as a musicologist-pianist as demonstrating a long and rich history of women music-makers and, therefore, evidencing precedents—her-stories—for the creative contributions of women now. My time comes to an end and I am left feeling proud to have represented Price’s music and legacy here, today.

After my performance, I tweeted the following thought-through (but clearly not proof-read) thread expressing my disappointment:

My goal with this post was to juxtapose this paper with Price’s music and career, spotlighting the implications of uneven power and access therein.

3. His talk was called “I have nothing to say.”

Some people therefore chose to listen to a man who has “nothing to say” over the music of an African American woman composer who has historically been silenced and is barely heard in this current day.

Let that sink in.

— Samantha Ege (@samantha_ege) July 7, 2018

Wrapped up in my post was the criticism of the fact that, being a university professor, the speaker of “I Have Nothing to Say,” has access to this kind of platform year-round, while marginalised voices only get amplified in the specific and limited spaces that society has carved out for them.

My critique is not about the individual, but about the systemic and institutionalized undermining of underrepresented voices, even at a conference designed to amplify them. The fact that such a work was placed on such a program evidences the extent to which we are so conditioned to ensuring the most powerful and privileged voice speaks in every single space, even when they acknowledge they have nothing to say.

Since posting that evening to both Twitter and Facebook, I have received a backlash on the latter, one that is, at present, unaffiliated with the organisers of the event. It has, however, attempted to derail the conversation. Apparently I was only upset because my program faced competition from other papers. Maybe I should have looked into the scheduling to make different arrangements. Or I should have found out what the speaker’s talk was about because there is a chance that I would have enjoyed it. Repeatedly, the onus was placed on me to reach out to the “token white man” and better understand his position. I also learned something new: passing judgement on a presentation because of its title is no better than passing judgement on a composer because of their gender. However, I was under the impression that the paper title was a choice and that Price’s identity as a black woman was not.

Anyway, I did not judge by the title. I judged by the abstract:

When one of the organisers of this conference suggested in a Facebook exchange on someone else’s post that I should submit an abstract for a paper, I was surprised. And a little frightened. What could I possibly contribute to such an event? I am the problem. I am a white, old, straight man with power and privilege. Surely my voice could only be heard by others as a violence in this context. Surely, my job is to get out of the way, to shut up, to not be heard. Surely, the only thing I could ethically and honourably bring to this is my listening. But then I felt that this is what needs to be said. I am and old straight white man who says that the job of people like me is to actively get out of the way, actively cede power and authority, actively be told, actively shut the fuck up. So I decided to use the occasion to practice a way of speaking that does those things, gets out of the way, cedes power and authority, gets told, shuts the fuck up. To practice speaking which listens. A listening-speaking. So that’s what I am trying to do in this paper. To enact a listening-speaking that gets out of the way, cedes power and authority, gets told, shuts the fuck up.

The speaker’s participation was invited and his proposal both encouraged and evidently accepted by the organizers. The abstract presents a sense of knowing better. “Surely my voice could only be heard by others as a violence in this context.” Yes. “Surely, my job is to get out of the way, to shut up, to not be heard.” Yes. “Surely, the only thing I could ethically and honourably bring to this is my listening.” Yes! “But…”

Ultimately, what needed to be said, actually needed to be done. The enacting of a listening-listening with neither platform nor audience would have been a powerful statement, quietly powerful, but powerful nonetheless. To reiterate, not all platforms are made equal—could I, realistically, have told him to shut the fuck up? How would that have sounded? How would I have sounded?

The derailing responses I have received pointedly ignore how the very presence of this paper disrupted the multiple and intersectional conversations happening in that moment. It distracted from the rarity of these subjects and their platform, and quite materially, culled an audience who could and should have been doing the very listening the abstract advertises. Scheduling this paper restored the speaker’s position to the center, and re-centered his power and authority to speak about everything and “nothing.” His privilege remained intact. In the midst of the most diverse and pertinent themes was the voice that has, both historically and to this day, spoken over the top of so many others.

“Trocadero Piano Player” by Flickr User Pierre Metivier (CC BY-NC 2.0)

I chose not to reach out directly to the institution nor its organisers because of the emotional labor this would entail. To put the issue forward in a quiet behind-the-scenes way that is sensitive to those who created the issue, is to chip away at my voice and its power. On the otherhand, to project the issue with a loud “shut the fuck up” is to perform a type of power and privilege on a platform that I do not have. I enact a public conversation here via Sounding Out! so that this experience may inform wider work towards diversity and representation. I enact this conversation in order to progress definitions of inclusion to a point where the choice to engage the dominant voice factors in a listening-listening as an exceedingly valuable contribution to the narratives offered by lesser heard voices.

I have since received a written acknowledgement from the organizers of this problematic programming, with a formal apology for the impact. But I must bring to light the important action of two allies, in particular, who recognised the emotional work required of me to bring this forward institutionally. They offered to continue the conversation on my behalf. We talked about the way in which the ensuing discussion must center listening. We shared that the process towards inclusivity may result in mistakes being made along the way. We discussed that while compassion and sensitivity can be important parts of the dialogue, I cannot afford to extend that compassion and sensitivity without becoming emotionally drained. And so, they wrote to the institution with the message of actively learning and making efforts towards change. I am so grateful for that allyship because while I knew that my voice would be heard, I could not guarantee how it would be heard. After all, if there is one take away to be had from this experience, it is that regardless of intention—and regardless of occasion—the dominant voice is very much conditioned to speak up, and speak over. And the dominant ear cannot help but listen.

So, how do I move forward?

My music and my message is powerful.

—

Featured Image: Courtesy of Author

—

Samantha Ege is a British musicologist, pianist and teacher based in Singapore. She is a Ph.D. candidate in Music at the University of York, UK. Her research focuses on the aesthetics of Florence Price. As a pianist, her focus on women composers has led to performances in Singapore (supported by the British High Commission and International Women’s Day), and lecture-recitals at the University of York, the Chicago Symphony Center and the Women Composers Festival of Hartford, USA. Her album Four Women: Music for Solo Piano by Price, Kaprálová, Bilsland & Bonds reflects her journey into a rich and unrepresented repertoire.

Samantha Ege is a British musicologist, pianist and teacher based in Singapore. She is a Ph.D. candidate in Music at the University of York, UK. Her research focuses on the aesthetics of Florence Price. As a pianist, her focus on women composers has led to performances in Singapore (supported by the British High Commission and International Women’s Day), and lecture-recitals at the University of York, the Chicago Symphony Center and the Women Composers Festival of Hartford, USA. Her album Four Women: Music for Solo Piano by Price, Kaprálová, Bilsland & Bonds reflects her journey into a rich and unrepresented repertoire.

She would like to thank Deborah Torres Patel for the gift of this mantra.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Spaces of Sounds: The Peoples of the African Diaspora and Protest in the United States–Vanessa Valdes

becoming a sound artist: analytic and creative perspectives–Rajna Swaminathan

Sounding Out Tarima Temporalities: Decolonial Feminista Dance Disruption–Iris C. Viveros Avendaño

Gendered Soundscapes of India, an Introduction –Praseeda Gopinath and Monika Mehta

On Whiteness and Sound Studies–Gustavus Stadler

Trackbacks / Pingbacks