Echoes of Ian Curtis: Film and the Punk Voice

Image of Alice Bag used with her permission (thank you!)

For full intro and part one of the series click here. For part two, click here. For part three click here. For part four click here. For part five click here.

Our Punk Sound series implicitly argues that sound studies methodologies are better suited to understanding how punk works sonically than existing journalistic and academic conversations about musical genre, chord progressions, and/or genealogies of bands. Alexandra Vasquez’s sound-oriented work on Cuban music, for example, in Listening in Detail (2014) opens up necessary conversations about the “flashes, moments, sounds” in music that bear its meanings and its colonial, raced, classed, and gendered histories in material ways people can hear and feel. While retaining the specificity of Vasquez’s argument and the specific sonic archive bringing it forth, we too insist on “an ethical and intellectual obligation to the question: what do the musicians sound like” (12) and how do folks identifying with and through these musical sounds hear them?

In this series, we invite you to amplify varied historicized “details” of punk sound–its chunk-chunk-chunk skapunk riffs, screams, growls, group chants, driving rhythms, honking saxophones–hearing/feeling/touching these sounds in richly varied locations, times, places, and perspectives: as a pulsing bead of condensation dripping down the wall of The Smell in Downtown LA (#savethesmell), a drummer making her own time on tour, a drunk sitting too near the amp at a backyard party, a queer teenager in their bedroom being yelled at to “turn it down” and “act like a lady[or a man]”. . .and on and on. In today’s essay Landon Palmer shows us how film may be just as responsible as music for how we remember the punk voice.

SOUND!

–Aaron SO! (Sounding Out!) + Jenny SO! (Sounding Out!)

—

In Joy Division’s 1979 song “Transmission,” singer Ian Curtis embodied several aspects of what made the group’s post-punk sound unique with the chorus, “Dance, dance, dance, dance, dance, dance to the radio.” As a piece of music, its repetition is intense and rousing, working as a compelling instruction that, when played loud enough, can be felt to the bone via Curtis’s deep timbre. At the same time, Curtis’s voice is robotic and distant, the signature of the group’s bleak sound that signified the post-industrial alienation of Thatcher-era Manchester. A historically specific critique of media, “Transmission” plays out a loss of agency. In the 21st century, however, the song has circulated more as a self-referential testament to Joy Division’s – and Curtis’s – musical skill, a container and a summary of myth.

Image by Ho-Teng Chang @Flickr CC BY.

To adopt Alexandra Vasquez’s question that has framed this series, what happens to representations of punk sound as they change over time? I argue that the cinematic techniques employed in presenting Ian Curtis and his voice in both 24 Hour Party People (Michael Winterbottom 2002) and Control (Anton Corbijn 2007) help us to understand the construction of a mythic punk voice.

Punk’s avoidance of comprehensibility, identification, and what Dave Liang calls “the prettiness of the mainstream song” have existed in awkward relation to narrative cinema, which requires legibility as a central component of storytelling (70, 71). While displacing the voice through fragmentation and asynchronous sound work has proven vital to theorizing and subverting cinematic norms, rarely has depicting a well-known punk singer’s voice in cinema translated to a cinematic punk aesthetic, as Stacy Thompson argues regarding the narrative and documentary Sex Pistols biopics Sid & Nancy (Alex Cox 1986) and The Filth and the Fury (Julien Temple 2000) (49-50). Even the revered punk documentary The Decline of Western Civilization (Penelope Spheeris 1981) renders punk voices legible by providing lyric subtitles. However, the two most notable cinematic portrayals of Ian Curtis–24 Hour Party People and Control, released during the band’s resurgence in 21st century popular culture–demonstrate competing interpretations for a punk voice’s place within filmmaking and put into play the question of how to interpret it.

Image by a town called malice @flickr CC BY.

Despite Curtis’s short lifetime, his voice continues to be amplified throughout popular culture. These extended echoes of his voice have participated in shaping its meanings and myth. In his book Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, Chris Ott writes that Joy Division’s music “defied imitation” (xiii); however, imitation (and citation) have fueled public memory of the band and augmented the myth of Ian Curtis. By the time Joy Division’s two LPs were re-released by Rhino in 2007, several contemporary bands–The Killers, Editors, Interpol and She Wants Revenge–built music careers that are openly indebted to this Manchester sound but distinct from its socio-historical context. Public memory of the group has been interpreted through uses of their music in the 1980s-set period pieces like Donnie Darko (Richard Kelly 2001) and Netflix’s Stranger Things (2016). The contemporary circulation of Joy Division’s music has extended to films that resurrect Curtis himself.

To start, 24 Hour Party People self-consciously stages an inquiry into Ian Curtis’s meanings and his contemporary resonance as part of the post-punk scene writ large. Chronicling the ‘70s-‘80s Manchester music scene through Tony Wilson (Steve Coogan), the attention-seeking TV personality and unlikely underground music patron who formed Factory Records, the film fits several tenets of Thompson’s definition of punk cinema in its “engage[ment] with history” and “critique [of] its own commodification” (64). A tongue-in-cheek historical guide, Wilson narrates via a fourth-wall-breaking blend of mythmaking, footnotes, and commentary that reflects upon the film’s historiography as he articulates it, and in so doing overtly selects myth over “truth,” stating, “When you have to choose between truth and the legend, print the legend” (itself a quote dubiously credited to John Ford). The film’s self-conscious performance of history extends to its musical numbers, where Winterbottom liberally blends imitation with the genuine article through a mix of archival and staged footage, thus overtly staging encounters with key moments in Manchester musical history. The film’s play with historiography does not go so far as to trouble its reinforcement of a canonical timeline.

It is in this spirit that 24 Hour Party People brings actor Sean Harris’s portrayal of Ian Curtis to life. In re-creating Joy Division’s performance of “Digital” at the Hacienda Club, Harris invokes Curtis’s jittery-mechanical dance style while his “voice” remains Curtis’s. Additionally, the film mixes ambient crowd noises with a band of actors performing in synch to the song’s studio recording. 24 Hour Party People not only preserves Curtis’s voice as an inimitable icon of this history, but places the studio recording of “Digital” as the authoritative version of the song within the nascent period of the Manchester scene, thus mapping this studio recording onto the band’s live sound (rather than implementing an existing live recording). Curtis’s voice is reproduced only through the most valuable, resonant historical record of it–the recorded commodity.

Image by bixentro @Flickr CC BY.

The retrospective framing implied by this choice speaks to the film’s greater approach to Ian Curtis as a figure best understood (or perhaps inevitably shrouded) via his posthumous legacy, and thus foregrounds Curtis’s transformation into myth. Due to the timing of his passing, there exists a relatively limited media archive of the actual Curtis compared to other late-20th century rock singers of similar influence. Beyond official performances on television, music video, and records, scant recordings of Curtis performing and speaking are available via silent 8mm home movies and archival audio interviews. Thus, 24 Hour Party People cannot resort to the historical record(ing) in all instances, and thus Harris’s voice proves central to interpreting Curtis off-stage. In recalling Joy Division’s notorious first encounter with Wilson, 24 Hour Party People portrays Curtis as intimidatingly sure-footed, confronting Wilson through quick, direct speech and locked eyes. Harris conveys the actorly qualities that so often typecast him in villain roles. Further complicating Curtis’s public image, Coogan’s Wilson provides a counter-narrative of the singer following his suicide, asserting to the audience that Curtis was not exactly the “dark and depressive…prophet of urban decay and alienation” that his music suggested, and recounts a rousing collective rendition of “Louie Louie” with the band to prove his point. The only instance in which Harris’s actual voice is used as Curtis’s singing voice, this cacophonous chorus depicts a Curtis participating in a deliriously muddled punk sound. Yet even this counter-narrative does not challenge the mythmaking of Ian Curtis, for it reinforces Curtis’s suicide as central to his meaning and value as a musician.

Music biopics have long bolstered definitive interpretations of a popular performer’s biography. In contrast to 24 Hour Party People’s self-conscious approach to mythmaking, Control is adapted from Deborah Curtis’s autobiography and directed by a former Joy Division photographer. Control’s most conventional choices as a rock biopic are the narrative associations the film makes between events in Curtis’s life and his songwriting, connecting Curtis’s music directly to his troubled marriage and the distress caused by his epilepsy. Control juxtaposes Curtis’s interior life with his production of music, cutting to the recording of “She’s Lost Control” after he learns that a client in his unemployment office has died of epilepsy, and featuring a performance of “Love Will Tear Us Apart” following a scene in which he tells his wife (Samantha Morton) that he no longer loves her. Control thus connects the singer’s authorial voice to the film’s narrative voice, arguing that the sounds Ian Curtis left behind are legible remnants of his biography. In so doing, the film deterministically situates his life through the framework of his death, his music serving a seemingly inevitable path to his suicide and thus transformation into musical myth (staged at the end with a crane shot rising up to the Manchester skyline during “Atmosphere,” indicating a ubiquitous echo of Curtis that has transcended the corporeal).

Punks in Manchester. Image by agogo @Flickr CC BY.

The film’s voicing of Curtis is articulated through Sam Riley’s performance, not through archival audio of the singer. As with 24 Hour Party People, Corbijn initially planned to have Riley and the supporting actors mimic their performances. However, during preproduction the band of actors rehearsed together until they were confident enough to play live shows for Joy Division fans. This convinced Corbijn to utilize them as a sort-of legitimate cover band for the purposes of embodying Joy Division’s history. Riley’s voice is notably higher than Curtis’s and is thus distinctive enough that it resonates comfortably alongside the numerous bands of this century whose leads “sound like” Curtis. Indeed, the resonance of Curtis throughout contemporary alternative rock may have helped make Riley more palatable as an authorized substitute for Corbijn and Joy Division fans. Such homage through imitation is reinforced by Control’s end credits, which features The Killers’ cover of “Shadowplay.” Both of these invocations of Curtis locate his value in his contemporary influence, not his historic place, an approach evident in Control’s less overt interest in post-punk’s socio-cultural context than 24 Hour Party People.

Control is uninterested in recreating the details of Joy Division’s history with exacting verisimilitude, forgoing the archive for a resonant aura of the band’s history. This approach is evident in Corbijn’s visual decisions – shooting the film in black-and-white memorializes the band through the stark photography with which Corbijn captured them – as well as his musical ones. In Control’s depiction of the band’s breakthrough performance on Tony Wilson’s (here played by Craig Parkinson) Granada Television program So It Goes, for example, Corbijn’s Joy Division perform the enduringly popular “Transmission” rather than “Shadowplay,” the song they actually played. Joy Division’s breakthrough television moment was further recast through “Transmission” in a fan-made Playmobil animation that curiously combines introductory audio of Parkinson’s Wilson from Control with Joy Division’s 1979 performance of “Transmission” on BBC2’s Something Else. Control not only situates Curtis’s singing voice coherently within authorial and narrative legibility, but also reflects and participates in contemporary popular memorialization of Joy Division regardless of the historical accuracy of such choices.

Pamela Robertson Wojcik argues that the human voice and its mediation through recording technologies is an important but overlooked component of cinematic performance. It is also vital to consider how famous voices travel and gain meaning through processes of imitation and citation–tropes of authenticity which pervade the musical biopic. While 24 Hour Party People and Control avoid many clichés of the musical biopic, narrative cinematic imperatives of legibility, coherence, and individual-centered storytelling motivate each film to participate in the production of rock star myth despite efforts at historical critique in the former or the austere style of the latter. Even in punk, rock star death is the most compelling biographical framework. The punk voice has long held a discordant relationships to cinematic norms, and these two films demonstrate how the translation of punk sound into cinematic soundscapes presents the inherent problem of recounting punk’s history.

–

Featured image “scream” by be.refreshed @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND.

–

Landon Palmer is a PhD Candidate studying Film and Media in the Department of Communication and Culture at Indiana University and recently defended a dissertation on the cross-industrial history of casting rock stars on film titled “Rock Cinema: A Transmedia History, 1956-1986.” He has published on popular music and moving image media culture in Music, Sound, and the Moving Image, iaspm@journal: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music, and Celebrity Studies.

–

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

G.L.O.S.S., Hardcore, and the Righteous White Voice – Chris Chien

If La Llorona Was a Punk Rocker: Detonguing The Off-Key Caos and Screams of Alice Bag – Marlen Ríos-Hernández

Riot-Grrrl, Punk and the Tyranny of Technique – Tamra Lucid

Playing with the Past in the Imagined Middle Ages: Music and Soundscape in Video Game

Each of the essays in our “Medieval Sound” forum focuses on sound as it, according to Steve Goodman’s essay “The Ontology of Vibrational Force,” in The Sound Studies Reader, “comes to the rescue of thought rather than the inverse, forcing it to vibrate, loosening up its organized or petrified body (70). These investigations into medieval sound lend themselves to a variety of presentation methods loosening up the “petrified body” of academic presentation. Each essay challenges concepts of how to hear the Middle Ages and how the sounds of the Middle Ages continue to echo in our own soundscapes.

Read all the previous posts here, and, HEAR YE!, in April 2017, look for a second series on Aural Ecologies of noise! –Guest Editors Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

–

Freed though they have been from the historiographical pit of the Dark Ages, the Middle Ages inevitably slip ever further into the past. Nonetheless, they have never been easier to visit. We have but to open our computers or turn on our televisions to be transported into the past. As any good Sci-fi show will tell you, we must be careful when we travel into the past; we can change things.

The medium on which I wish to focus – videogame – relies precisely upon on this ability to affect change. It takes aspects of filmic medievalism but must also confront an intrinsic interactivity. This interactive capacity may seem to authenticate further the experience of the past by creating a rich and responsive world but it also frees aspects of narrative agency from the control of game designers, composers, and sound engineers. In this article, I will demonstrate some of the ways in which issues of space/place, identity, orientalism/otherness, and the norms of the medium itself can play out. In recomposing the past – be that with a nod to authenticity, within the realms of historical metafiction, or even the imagined (neo-)medievalism of the fantasy genre – videogames create something that sits between the past and present that nonetheless has a profound effect on the public conception of the medieval soundscape. My focus here is on CD Projekt Red’s high-fantasy game The Witcher III: Wild Hunt, addressing not only the musical score but also wider aspects of soundscape such as vocal accent, foley, and manipulation of the aural field.

Still from The Witcher III: Wild Hunt.

.

The genre of fantasy could be described as medievalist in origin and aesthetic, taking clear inspiration from the medieval world and often using it, or a close approximation, as a geographical, historical, and cultural setting. Many of the more fantastical elements of fantasy too are drawn from medieval bestiaries and the genre of the medieval romance. The late Umberto Eco popularised the term neo-medievalism, albeit in a rather pejorative sense and in opposition to ‘responsible philological study’, to describe this interaction between medieval history and the fantastical. Perhaps due to the rather negative associations of neo-medievalism, both terms tend to be used somewhat interchangeably today.

A divide could perhaps be suggested as to whether medieval aspects are presented as unproblematic and nostalgic, or treated in a more critical and distanced manner. For instance, David Marshall defines neo-medievalism as ‘a self-conscious, ahistorical, non-nostalgic imagining or reuse of the historical Middle Ages that selectively appropriates iconic images…to construct a presentist space that disrupts traditional depictions of the medieval.’ In contrast, Kim Selling notes of medievalism that, after the breakdown of modernist historical metanarratives, the pre-modern world of the medieval offers a ‘rich, satisfying, and authentic’ counterpoint to the ‘profound social, spiritual, and political dislocation’ of postmodernism. From this viewpoint, the world of medievalist fantasy offers pure escapism back to a world in which old certainties can be re-asserted; perhaps, as Elkins notes, a reaction against the rationalistic, anti-heroic, materialist, and empiricist bent of modern society.

Regardless of the author’s framing of ‘the medieval’, it offers many narrative advantages. As Kim Selling has noted, in placing an imagined world in a simplified version of the Western European Middle Ages, the fantasy author can make use of narrative shorthands. The world of kings, queens, knights, peasants, dragons, magic, witches, and elves is already known from myth and fairy tale. These aspects require no explanation but rather build upon a tradition of understood western folkloric conventions – conventions that can also imply certain types of social structure.

The Witcher is certainly situated in a simplified medieval Europe (see the similarity between the coasts of Poland and Nilfgaard) and it clearly occupies a world with presentist concerns. More than this, its extreme use of narrative indeterminacy betrays a staunch adherence to postmodern concepts of storytelling and a distinct anti-heroic edge. The player navigates a world of many shades of grey, often choosing the lesser of many evils. They make decisions – which often result in unintended consequences – based on their own morality and desired outcomes. This said, perhaps the question of whether it could be defined as medievalist or neo-medievalist depends on the actions of the player and precisely the kind of narrative they construct.

An early example of unintended consequences and choosing the lesser of many evils

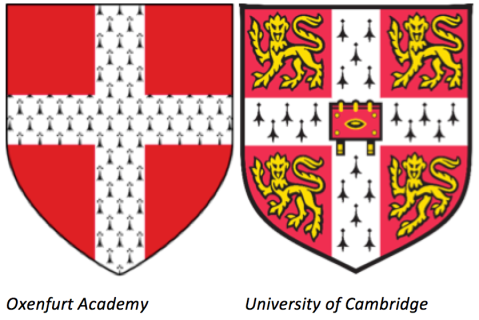

The visual world inhabited by The Witcher certainly relies on appropriating iconic images; the analogue aural world on appropriating iconic sounds, accents, and musical ideas as the player continuously explores regions with distinct identities, social structures, urban/pastoral settings, and religions. The rational, urban, and merchantile world of Oxenfurt (a city famous for its world-class university with a crest clearly based on that of the University of Cambridge and a name that hints at the university town of Oxford’s medieval etymology) and Novigrad are clearly at odds with the rural peasant life of the Velen wastelands or the Celtic imagery of the Skellige isles.

The landscape and soundscape of Oxenfurt

The landscape and soundscape of Novigrad

The landscape and soundscape of Velen (with multiple examples of the ‘combat music’)

The landscape and soundscape of Skellige (with the ‘combat music’ adapted for this area)

Like much medievalist fantasy the tension between rationalism and the fantastical is one of the central elements of dramatic tension. As the great cities of this world grow and the expansionist Nilfgaardian Empire press forward, the pre-modern world of The Witcher shrinks. Allied to the spread of rationalism, we also see the ‘Church of the Eternal Fire’ (an identifiable stand-in for Christianity) seek to eradicate magic, non-human populations, and more identifiably ‘pagan’ religions. The architecture of its buildings invite comparison with European sacred architecture and its witch hunters and inquisitions with particularly regrettable episodes of European history.

The Temple of the Eternal Fire burning people at the stake

Just as the visuals employ iconic imagery to imply certain ideas, the soundscape’s most important function is to provide the aural analogue of this. One aspect is the score. Within this, individual musical stems are layered in response to player actions. As the composer Marcin Przybylowicz noted in a recent interview with the Tech Times ‘[t]he cues (that were interactive) are divided into smaller layers, which come together, in the case of a combat cue, only when we are dealing with a very powerful enemy. If the enemy is small … only the first layer of the piece will play’. These layers are re-orchestrated in each area so as to preserve its aural identity. In a separate interview with IC-Radio.de, Przybylowicz notes:

No Mans (sic.) Land [Velen] is a war ravaged land… It’s also full of slavic references, pagan beliefs etc. …. Then, there’s Novigrad – the biggest city in northern kingdoms. … I decided music in Novigrad should be more civilized – that’s why there are lots of string instruments playing there (dulcimer, bouzouki, guitars, lutes, cimbalom etc.), and overall tone of the music is lighter, [and] reminds [me] a bit music of [the] Renaissance. Finally, [the] Skellige Isles – [a] region with Celtic, Scottish and Norse references, that had to be reflected in music as well. Use of bagpipes, flutes and Scandinavian folk instruments corresponds with that setting. On top of that, I had to think how it would all work together. That’s where our themes come in … We use those themes in every major location …. [and] we reorchestrate them with instruments corresponding to a particular region.

Combat music in Velen and Skellige respectively. Note how both utilise the orchestration of their own respective areas to alter the main theme and how additional layers are added to the music depending on the intensity of the fighting.

In viewing the different medievalisms on offer in this game, a comparison of the three areas mentioned above is instructive. The Skellige isles, an archipelago which looks curiously like Scottish islands, are occupied by inhabitants with Irish accents. As can be heard in the videos above, the clearly Celtic-influenced music of this area supports this association and the relative lack of diegetic music in this area, combined with natural sounds (the sea, wind, storms) combine to give a sense that the music is a part of the geography. Celtic folk music as a shorthand for the Middle Ages is nothing new. Simon Nugent has noted the tendency of many historically-situated films to draw on Celtic influence. His work has shown that the creation of ‘Celtic’ folk has little to do with a discrete geographical area or with historical accuracy but rather is a modern marketing creation that plays on associations with nature and an escape from modernity. This is precisely the case in The Witcher where, rather than utilising a real historical Celtic medieval repertory, it instead draws on aural cues from the popular medievalism of the filmic soundscape tradition, filtered through the need for an indeterminate score. This ‘packaging’ brings with it associations of an ‘authentic’ Celtic folk tradition as a remnant of the ‘true folk tradition’ that once existed for everyday people elsewhere.

We can perhaps see a link to the works of fantasy writers such as Gael Baudino and Patricia Kennealy-Morrison who turn to pagan Celtic sources as an alternative to what they perceive as the medieval Christian degradation of women, as Jane Tolmey has noted. This association between pagan prehistory, matriarchy, and freedom for women seems a common theme in the popular conception of the past, echoed by theorists such as Albert Classen. The fact that Skellige evokes a recognisably ‘Celtic’ soundscape (relying heavily on the Polish Folk band Percival who collaborated on both new works and who took several from a previous album which were then adapted for indeterminate playback) therefore comes with many associations, drawn almost entirely from the filmic soundscape tradition. This is a pre-modern, pagan land; a land with an authentic peasant class: roughhewn but honest. This Celtic imagery and soundscape also offers a counterpoint to the sexual politics of other areas. Women can more easily participate in areas which might otherwise be seen as male-dominated: depending on the actions of the player, a woman may rule Skellige. A matriarchal class of priestesses govern the region’s predominant religion in stark contrast to the male Priests in other areas. The soundscape here is therefore absolutely crucial to the identity of this area. In creating a Celtic sonic identity – equal part music and accent – the game designers have created a rich culture that need only be hinted at to be understood.

By contrast, the urban world of Novigrad and Oxenfurt is far less folk-influenced. Unlike the other areas of the game, it does not draw so heavily on either the pre-existent or newly composed music of Percival, make such explicit use of folk instrumentation, and seems far more closely related to a Renaissance dance music tradition. The urban/pastrol divide is enhanced by the sounds of a busy city compared to the sounds of nature and the frequent cries of the townsfolk give a sense of bustling urban life (this time with accents from the North of England – compare HBO’s Game of Thrones).

Compared to the wind instruments and female vocals of Skellige, percussion and plucked/struck strings predominate. There is indeed more of a Renaissance feel in an area already touched by modernity. Most notably, there is more diegetic music in these two cities. We frequently see and hear small Renaissance dance bands, using period instruments, entertaining crowds (watch from around 3:45 of the above video of Novigrad for an example; note how diegetic music slowly enters the soundtrack as they are approached). Perhaps the most significant diegetic moment, however, is the song by the Trobaritz Priscilla. The audio and visuals are surprisingly well matched, and the tuning of the lute adds emphasis to the fact of live performance. As a video cut-scene, this is one of few moments in the game where the player has no ability to affect their environs and must simply watch and listen.

Priscilla’s song

Far more so than in other areas, the music in Novigrad and Oxenfurt is for and by people. This is in marked contrast to the soundscapes found on Skellige and in Velen where the music is almost purely non-diegetic. In contrast to the pre-Christian matriarchal associations of the priestesses of Skellige is the aural handling of the Temple of the Eternal Fire in Novigrad and its male priests. As Adam Whittaker has recently identified, there is a clear link between musicological discourse on purely vocal performance in Christian sacred space in Early Music, and its representation on screen. Male a capella voices, and a ‘chanting’ vocal style (again hinting at plainchant, rather than using pre-existent chant music), are often used to denote the aural identity of a church. Precisely this kind of vocal delivery is added to the soundtrack as the player moves closer to the Temple of the Eternal Fire, explicitly linking this Christian association with the aural presence of the Temple. The contrast with the female-dominated vocals elsewhere enhances the distinction and re-enforces the links between the ostensibly pre-Christian worlds of Skellige and Velen and the Christian associations made in Novigrad.

Approaching the Temple of the Eternal Fire

The music of the Velen wasteland and the neighbouring White Orchard, like Skellige, is more folk influenced, yet clearly distinct. Gone are the Celtic folk influences; instead, this area fuses a cinematic pastoral idyll (again laden with nature sounds and with a peasantry speaking with West Country accents – compare the idyllic ‘Shire’ in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings) with a dark and sinister undertone which draws on the ‘otherness’ of many non-western and folk instruments, particularly the kemenche, electric cello, hurdy gurdy, bowed gusli, gheychak, and the bowed yaylı – the vast majority of which only enter the soundscape in this area. The use of the medieval as a source of dangerous and primitive ‘otherness’ is common at the moment (evidinced, for instance, by the many recent descriptions in the West of the so-called Islamic State as ‘medieval’) and draws on modernist thought which characterized the middle ages as a period of dark and dangerous alterity between the glories of antiquity and the Renaissance.

That the soundscape of The Witcher draws on competing categorisations of the medieval as ‘dangerous’ and ‘pastoral’ says much about the mutability of medievalisms. Musically, this ‘otherness’ can be expressed as a kind of orientalism, both exotic and dangerous, and the microtonal inflections and use of glissandi here give a sinister undertone to what is otherwise a quintessentially pastoral film score. This area has one of the most memorable parts of the entire soundtrack ‘Ladies of the Wood’, underscoring a genuinely horrific narrative and visuals (some of the consequences of which are shown in the first video of this post with a lengthier section of the music given below). The exotic instrumentation combined with the driving repetition, at odds with an audio usually so responsive to the player’s actions, makes the experience unsettling and claustrophobic.

Ladies of the Wood

Taken together, these very distinctive sound worlds serve to demonstrate some of the many medieval soundscapes which permeate our collective consciousness. In utilising iconic aural cues, composers and sound designers in a neo-medievalist tradition can conjure up particular cultural and social structures with ease, taking many of the shorthands which have emerged from the TV and film traditions in recent years. The indeterminacy inherent to videogame, and the common response of using audio stems, means that the soundscape moves far beyond what is possible in TV and film. However, it also makes problematic the concept of using real, historically-informed music from the period being invoked which would not be able to respond to the interactivity of the world. In The Witcher, the decisions we make effect the world around us, including its soundscape. The effect is crucial both to helping to conjure the world of The Witcher and to helping us feel immersed in it – perhaps paradoxically this may make the soundworld invoked seem more authentic even if it simultaneously reduces the possibility of using ‘authentic’ historical repertoire.

—

Featured image by Carlos Santos @YouTube CC BY.

—

James Cook is a University Teacher in Music at the University of Sheffield. His work focuses on the musical period that falls neatly between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. In particular, the ways that musical cultures in this period interact and how expatriate groups (merchants, clergy, and nobility) imported and used music. Some of his work (like this essay) concerns the representation of early music on stage and screen, be that the use of ‘real’ early music in multimedia productions, the imaginative re-scoring of historical dramas, or even the popular medievalism of the fantasy genre.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #49: Sound and Sexuality in Video Games – Milena Droumeva and Aaron Trammell

Sounding Out! Podcast #29: Game Audio Notes I: Growing Sounds for Sim Cell–Leonard J. Paul

Papa Sangre and the Construction of Immersion in Audio Games— Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo

The Dark Side of Game Audio: The Sounds of Mimetic Control and Affective Conditioning – Aaron Trammell

Recent Comments