Sound Bites: Vampire Media in Orson Welles’s Dracula

Welcome back to our continuing series on Orson Welles and his career in radio, prompted by the upcoming 75th anniversary of his 1938 Invasion from Mars episode and the Mercury Theater series that produced it. To help us hear Welles’s rich radio plays in new and more complicated ways, our series brings recent sound studies thought to bear on the puzzle of Mercury‘s audiocraft.

Welcome back to our continuing series on Orson Welles and his career in radio, prompted by the upcoming 75th anniversary of his 1938 Invasion from Mars episode and the Mercury Theater series that produced it. To help us hear Welles’s rich radio plays in new and more complicated ways, our series brings recent sound studies thought to bear on the puzzle of Mercury‘s audiocraft.

From Mercury to Mars is a joint venture with the Antenna media blog at the University of Wisconsin, and will continue into the new year. If you missed them, check out the first installment on SO! (Tom McEnaney on Welles and Latin America) and the second on Antenna (Nora Patterson on “War of the Worlds” as residual radio).

This week, Sounding Out! sinks its teeth into Orson Welles’s “Dracula,” the first in the Mercury series, and perhaps the play that solicits more “close listening” than any other—back in 1938, Variety yawned at Welles’s attempt at “Art with a capital A” and dismissed his “Dracula” as “a confused and confusing jumble of frequently inaudible and unintelligible voices and a welter of sound effects.” Here’s the full play, listen for yourself:

It’s a good thing that our guide is University of South Carolina Associate Professor and SO! newcomer Debra Rae Cohen. Cohen is a former rock critic, an editor of the essential text on radio modernism, and has also recently written a fascinating essay on the BBC publication The Listener, among other distinguished critical works on modernism. Below you’ll find the most detailed close reading of Welles’s “Dracula” (and of Welles as himself a kind of Dracula) ever done.

Didn’t even know Welles ever played Count Dracula? That’s just the first of many surprises you’ll discover thanks to Debra Rae’s keen listening.

So (to borrow a phrase), enter freely and of your own will, dear reader, and leave something of the happiness you bring. – nv

—

Orson Welles

It’s one of the best-known anecdotes of the Mercury Theater: Orson Welles bursts into the apartment where producer John Houseman is holed up cut-and-pasting a script for Treasure Island, the planned debut production, and announces, only a week before airing, that Dracula will take its place. At a time when Lilith’s blood-drenched handmaidens on the current season of True Blood serve as an analogue for our own cultural oversaturation with vampires, it’s worth recalling why, in 1938, this substitution might have been more than merely the indulgence of Welles’s penchant for what Paul Heyer calls “gnomic unpredictability” (The Medium and the Magician, 52).

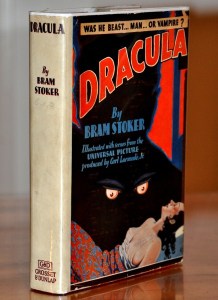

In fact, 1938 was a good year for vampire ballyhoo; Tod Browning’s 1931 Dracula film had been rereleased only a month before to a new flurry of Bela Lugosi press. Welles’s last-minute switch was a savvy one, allowing him to capitalize on the publicity generated by the continuing popularity of the film (and the popular Hamilton Deane and John Balderston stage adaptation from which it largely drew), while publicly disdaining its vulgarity in favor of what he seemed peculiarly to consider the high-culture status of Stoker’s original novel. Here he is defending the book:

But more importantly, Welles’s production reclaimed and exploited the novel’s own media-consciousness, a feature occluded in the play and film versions, and one to which the adaptation into radio adds, as it were, additional bite. Dracula introduced several of the radio innovations we’ve come to associate with the Mercury Theater (and The War of the Worlds in particular)—first-person retrospective narration, temporal coding, the strategic use of media reflexivity—but Stoker’s novel may have made such innovations both alluring and inevitable.

Stoker’s Dracula is made up of a patchwork of documents—shorthand diaries, transcribed dictation cylinders, newspaper clippings—that do not simply serve as a legitimizing frame, as in Frankenstein. Instead, they are deeply self-referential, obsessively chronicling the very processes of inscription and translation between media by which the novel is built. Confronted with the terrible threat of Dracula free to prey on London’s “teeming millions,” Mina Harker vows thus: “There may be a solemn duty, and if it come we must not shrink from it. …I shall get my typewriter this very hour and begin transcribing.” Processes of ordering information serve, as critics since Friedrich Kittler have noted (see for example here, here, and especially here), as the way to combat the symbolic threat of vampirism that, as Jennifer Wicke argues, stands in for “the uncanny procedures of modern life,” and a threat that may have already colonized intimate spaces of the text itself (“Vampiric Typewriting,” 473).

That threat, in the novel, sounds oddly like . . . radio. Seeping intangibly through the cracks of door frames, invading domestic spaces, riding through the ether “as elemental dust,” materializing abruptly in intimate settings, communicating across land and sea while rendering his receiver passively malleable, Stoker’s Dracula is terrifying by virtue of his insidious ubiquity, a kind of broadcast technology avant la lettre.

A 1931 Grosset & Dunlap edition of Dracula, with images from Browning’s film.

In adapting Dracula for radio, then, Welles could play on the deep division in the novel between the ordered forces of inscription and the Count’s occult, uncanny transmissive force in order to exploit the anxieties connected with the medium itself. Even the double role Welles plays in the production—both Dracula and the doctor Arthur Seward—functions in this regard as more than bravura.

Seward’s primary role in the drama as compère, or advocate, threads together Dracula’s multiple documentary “narration,” through what became the familiar Mercury device of retrospect-turned-enactment. As Seward, Welles performs an argumentative and editorial function that’s nowhere in Stoker’s novel, where the various documents make up a file that is explicitly uncommunicated, because unbelievable, for a case no longer necessary to make. Shuffling the various documents that make up the “case,” Seward stands outside of definite place, but also outside of time, animating “the extraordinary events of the year 1891” by directly addressing an audience of a medium that does not yet exist. Here is part of Seward’s address:

Seward is our first “First Person Singular,” and yet his persona is unsettlingly thin. Though his voice at the outset is strong and urgent, it feels bland compared with the dense goulash of “Transylvanian” effects that competes for our attention through the first ten minutes of the production—hoofbeats, thunder, wolf howls, whinnies, the sound of a coach seemingly about to clatter to bits, the singsong of prayers muttered, perhaps, in some exotic foreign tongue. The “documents” on which Seward’s claim to the trust of the audience rides are overwhelmed by the sound that saturates them. Here is the scene:

It’s not until nearly 20 minutes into the production that Seward reveals his own connection with the story—as the lover of Lucy Westenra—and from this moment forward Welles allows Seward’s authority in the “present” to be eroded by his bland inefficacy in the scenes of the “past.” By Act II, he has ceded authority by telegraph to Dr. Van Helsing (Martin Gabel, in a brilliantly crafted performance):

Without the didactic authority of Van Helsing and with small claim on audience sympathy, Seward becomes, through the second half of the production, a strangely insecure advocate, whose claim on authentic first person experience often disrupts, rather than augments, his role as presenter.

The listener does not consistently “follow” Seward either narratively or sonically—indeed, he is often displaced to the sonic periphery by Dr. Van Helsing. In the final confrontation with Dracula, Seward is explicitly shooed to the outer margins of the soundscape to pray.

Here the technical exigencies of Welles’s double role support a subtext that his unmistakable voice has already suggested: that Seward is here the “other” to Dracula (as, later, his Kurtz would be to his Marlow), waning as he waxes. As Lucy is weakened through Dracula’s occult ministrations, so too is Seward sapped of vitality, his romantic passages voiced as strangely bloodless, while Dracula’s wring from Lucy an orgasmic sonic response. Penetrating the intimate chamber Seward ineffectively desires to protect, Dracula replaces him as the production’s central sonic presence—who even when silent, possesses the sonic space.

Contrast Seward’s feeble voice during his night-time vigil here,

to Dracula’s seductive visit here,

Welles needed to distinguish his Dracula from Lugosi’s, employing, rather than an accent, a kind of sonorous unplaced otherness. But his performance shares the ponderous spacing of syllables that, in Lugosi’s case, derived from phonetic memorization of his English script; in other words, Welles is “recognizable” as Dracula without “playing” him. As an analogue to Lugosi’s glacial movement, Dracula’s voice is here surrounded by depths of silence in an otherwise effect-busy soundscape.

From the beginning, Dracula is also sonically on top of the listener, uncomfortably intimate, as in this scene of a close shave:

And although Dracula’s voice is not heard for a full thirteen minutes after Lucy’s death, it nevertheless seems to inhabit all available silences, until he quietly seeps through the door frame of Mina Harker’s bedroom:

The closely-miked phrase “blood of my blood” is reprised throughout the second half of the production—it is repeated seven times, by both Dracula and Mina (Agnes Moorhead), though it occurs only once in the novel—underscoring the ineffable aurality of Dracula’s “transmission.” The line doesn’t present as meaning, but as a tidal echo, the pulse of a carrier wave. While it signals an action unrepresentable to the ear—Dracula’s literal bite or its resonances of memory and desire—it also functions as a “signal” in the sense that Verma describes, as a repetitive element that compels listenership like an incantation (Theater of the Mind, 106). This is the power against which the “documents” are marshaled, the power of “pure” radio—ironically the very power that allows them to be shared. And the hypnotic thrum of radio rips them to shreds.

Indeed, the closing minutes of the drama present the vampire hunters, the novel’s forces of inscription, as an array of anxious noises marshaled against this lurking silence. The frenzied pacing of the final chase back to Transylvania—an element of Stoker’s novel that both plays and film sacrificed—gathers momentum through ever-shorter “diary entries” delivered, breathlessly, over the sound effects of transport:

Welles exploits the familiarity of his audience with a mechanism that Kathleen Battles calls a “radio dragnet”; the forces of order deploy the ubiquity of radio itself to shore up social cohesion, enlisting the audience within their ranks (Calling all Cars, 149). But here that very process is, simultaneously, unsettled and undermined by the identification of Dracula himself with invisible transmission. As Van Helsing repeatedly hypnotizes Mina to tap in on her communion with Dracula—radio, in a sense, deploying radio—the listener is aware of being both eavesdropper and the sharer of rapport, a position that implicates her in Mina’s enthrallment. Here is part of the sequence:

This identification intensifies in the climactic sequence, completely original to Welles’s adaptation, in which Dracula, at bay before his enemies, weakened by sunlight, calls upon the elements of his undead network:

This tour-de-force moment for Welles is also the point when radio shatters the documentary frame and undermines its logic. Though Mina hears Dracula, the others do not, and as Van Helsing’s “testimony” attests, even she does not remember it. This communication can’t, then, be part of Seward’s “evidence.” Rather, it is the radio listener—Dracula’s real prey—who who has received Dracula’s transmission, who has heard across time and space what no one else present can hear: “You must speak for me, you must speak with my heart.”

Although Mina refuses this rapport by staking Dracula at the last possible second—or does she refuse it? Is this not perhaps the Count’s secret wish?—the effect of the uncanny communion persists beyond Seward’s summation, beyond Van Helsing’s subsequent account of Dracula’s end. It renders almost unnecessary Welles’s famous playful post-credits epilogue, in which he abruptly adopts Dracula’s tones to tell us that, “There are wolves. There are vampires”:

But with the hypnotic reach of radio at your disposal, who needs them?

—

Featured Image Adapted from Flickr User Andrew Prickett

—

Debra Rae Cohen is an Associate Professor of English at the University of South Carolina. She spent several years as a rock & roll critic before returning to academe. Her current scholarship, including her co-edited volume Broadcasting Modernism (University Press of Florida, 2009, paperback 2013) focuses on the relations between radio and modernist print cultures; she’s now working on a book entitled “Sonic Citizenship: Intermedial Poetics and the BBC.”

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“The Sound of Radiolab: Exploring the ‘Corwinesque’ in 21st Century Public Radio”–Alexander Russo

“One Nation Under a Groove?: Music, Sonic Borders, and the Politics of Vibration”–Jonathan Sterne

“Radio’s ‘Oblong Blur’: Notes on the Corwinesque“– Neil Verma

Tags: Bela Lugosi, Bram Stoker, Broadcast Technology, Debra Rae Cohen, Dracula, First Person, From Mercury to Mars, Gnomic Unpredictability, hypnosis, Inscription, Intimacy, Jennifer Wicke, John Houseman, Kathleen Battles, Listeners, Modernism, Neil Verma, Orson Welles, Radio Dragnet, Radio Plays, Signals, Sonic Space, Sound Effects, Uncanny, Vampires

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Rhetoric After Sound: Stories of Encountering “The Hum” Phenomenon

- Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions

- Wingsong: Restricting Sound Access to Spotted Owl Recordings

- Listening Together/Apart: Intimacy and Affective World-Building in Pandemic Digital Archival Sound Projects

- The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Trackbacks / Pingbacks