Radio’s “Oblong Blur”: Notes on the Corwinesque

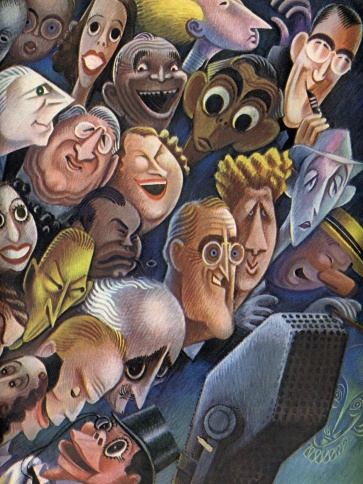

Miguel Covarrubias, untitled iIlustration to “Radio I: A $140,000,000 Art,” Fortune (May, 1938).

Editor’s Note: Today, Neil Verma kicks off our summer series “Tune In to the Past,” which explores the life and legacy of radio broadcaster Norman Lewis Corwin, the “poet laureate of radio” who died last summer at the age of 101. Corwin, pictured in the icon to the left with actress Peggy Burt around 1947, passed too quietly into the ether–as, unfortunately, has too much of radio history. Sounding Out!‘s three-part exploration of his legacy by radio scholars Verma, Shawn VanCour (July), and Alex Russo (August) not only gives his work new life (and critique), but also speaks to the growing vitality of radio studies itself. As I mentioned this past March in my round-up of the 2012 Society of Cinema and Media Studies conference, radio scholarship is on the rise–a Radio Studies Special Interest Group was established at SCMS this year, reaching a critical mass–and scholars are finding new and innovative ways to approach radio’s unique silences. We are proud over here at SO! to broadcast the future of radio studies by helping you “Tune In to the Past” this summer, so get ready for an array of voices–living and dead, textual and aural–spirited debate, and great sound history, in both senses of the word. So don’t touch that dial. –JSA

Editor’s Note: Today, Neil Verma kicks off our summer series “Tune In to the Past,” which explores the life and legacy of radio broadcaster Norman Lewis Corwin, the “poet laureate of radio” who died last summer at the age of 101. Corwin, pictured in the icon to the left with actress Peggy Burt around 1947, passed too quietly into the ether–as, unfortunately, has too much of radio history. Sounding Out!‘s three-part exploration of his legacy by radio scholars Verma, Shawn VanCour (July), and Alex Russo (August) not only gives his work new life (and critique), but also speaks to the growing vitality of radio studies itself. As I mentioned this past March in my round-up of the 2012 Society of Cinema and Media Studies conference, radio scholarship is on the rise–a Radio Studies Special Interest Group was established at SCMS this year, reaching a critical mass–and scholars are finding new and innovative ways to approach radio’s unique silences. We are proud over here at SO! to broadcast the future of radio studies by helping you “Tune In to the Past” this summer, so get ready for an array of voices–living and dead, textual and aural–spirited debate, and great sound history, in both senses of the word. So don’t touch that dial. –JSA

Norman Corwin in 1973 (Source: Arrowcatcher, Wikimedia Commons)

“I am a Dead Sea Scroll,” Norman Corwin, in an interview with writer Tom Lewis, 1992.

Rising to prominence in the 1930’s, radio dramatist Norman Corwin (1910-2011) aired a body of work of unsurpassed variety, reaching audiences upwards of sixty million with plays that range from “The Odyssey of Runyon Jones,” about a boy searching the afterlife for his beloved dog, to One World Flight, for which Corwin visited 17 countries seeking voices of peace. Often compared to such figures as Eugene O’Neill and Walt Whitman, Corwin was known for seventy years as the “Poet Laureate” of radio, an unofficial title invented for him and impossible to confer on another. I interviewed Norman for my book Theater of the Mind (University of Chicago Press, 2012). These remarks derive in part from those conversations.

Rising to prominence in the 1930’s, radio dramatist Norman Corwin (1910-2011) aired a body of work of unsurpassed variety, reaching audiences upwards of sixty million with plays that range from “The Odyssey of Runyon Jones,” about a boy searching the afterlife for his beloved dog, to One World Flight, for which Corwin visited 17 countries seeking voices of peace. Often compared to such figures as Eugene O’Neill and Walt Whitman, Corwin was known for seventy years as the “Poet Laureate” of radio, an unofficial title invented for him and impossible to confer on another. I interviewed Norman for my book Theater of the Mind (University of Chicago Press, 2012). These remarks derive in part from those conversations.

—-

In June of 1947, New Yorker writer Philip Hamburger published a profile of Norman Corwin, then already recognized as a distinguished radio dramatist. From Pearl Harbor to V-J Day, Corwin had staged daring plays to mark Allied milestones and earned frothy praise from the likes of Carl Sandburg, who called Corwin’s V-E Day show “On a Note of Triumph” one of the “all-time best” American poems.

Such acclaim was not universal. That same broadcast drew scorn from historian Bernard DeVoto, who called it a “mistake from the first line” full of “pretentiousness” and “bargain-counter jauntiness.” Like many others, DeVoto and Sandburg reacted to Corwin’s habit of excess by mimicking it. Hamburger’s profile caught that same bug. Billing itself as “The Odyssey of the Oblong Blur,” Hamburger tells a gauzy story of Corwin’s older brother building him a crystal set out of a box of Quaker Oats, and relates tall tales of Corwin’s artistry, like the time he spent two days trying to simulate the sounds of depth charges. And not only did Hamburger write the profile as a radio play, but he wrote it in the style of Norman Corwin.

What is that style, exactly? Thoughts on that question have been surprisingly minimal. When Corwin died last fall, commentators celebrated his life (see here, here, here and here), but the memorials lacked precisely the sense of scale to which both Sandburg and DeVoto responded. There was no voice to speak of Norman in a “Corwinesque” manner, in part because the man probably outlived more likely eulogists than anyone else in the history of broadcasting. Had he not outlasted them, Corwin would have been mourned by the avuncular elders of midcentury liberalism, like his friends Edward R. Murrow and Carl Sandburg or admirers Robert Altman, Walter Cronkite and Studs Terkel, any one of whom could have written a loving burlesque in Corwin’s voice.

But no one did, and no one can, not now. Who would get the joke, anyway? Collective experience of Corwin’s sound is passing out of living memory. Yet this very elapsing “afterlife” of the radio age, I feel, lends new richness to the question of the Corwinesque, an aesthetic that needs clarification both to give full credit to the man behind it, and, in a larger sense, to show how a theory of sound experience can “happen” at the twilight zone of collective human memory.

So what was “the Corwinesque” around 1947? What is it nowadays? What might it become in the future? In this post I’ll consider both the nature of the “Oblong Blur” and the methods we’ve tried to bring its ongoing odyssey into focus.

Philip Hamburger’s New Yorker profile, with illustration by A. Birnbaum

A High Wireless Act

In its profile, The New Yorker poked fun at how Corwin made unreasonable demands of sound (e.g. “Music: a universal theme, oscillator beneath, denoting pain of the world and bigness thereof, fading”) and let childish literary tactics run amok, as when the audience is called “Sons of a Sun spinning sadly through space.” In his era, Corwin’s penchant for such overwriting was an unavoidable aesthetic issue.

Corwin’s work was widely understood as a challenge to technicians and actors just for the sake of it. In the script for “New York: A Tapestry for Radio,” for example, a date scene contains this befuddling note: “Music: Love on brownstone stoop at three in the morning after an evening at the RKO Proctor Theater and a long walk in the park. It sustains, behind.” In “The Undecided Molecule,” meanwhile, we learn of a particle that refuses to select his destiny before “The Court of Physiochemical Relations.” Here are some of many tongue-twisting lines in verse:

I’d argue that Corwin’s writing is impressive here precisely because it’s so easy to botch in delivery. The style spotlights its own overworked literary calisthenics, saying: look at me trying so hard I might blow it.

In this way, the Corwinesque names a connection between the soaring and the buffoonish, a link that a contemporary called his “frontier spirit.” Thanks to this spirit, even when the prose was purple, the defect came across as that of an innovator. To keep that up, Corwin had to innovate constantly. That’s why his plays took on so many other forms – the letter (“To Tim and Twenty”); the lecture (“Anatomy of Sound”); the pageant (“Unity Fair”).

So one key to the Corwinesque was to walk a high wire without a net, another was to say so. Nothing confirmed both better than a fall. I’d wager many listened for a lousy line or overdone tune as part of the pleasure of it all. Indeed, it may be incorrect to evaluate Corwin’s aesthetic as poetic; think of the Corwinesque as broadcasting rather than writing, and its liabilities come across as dares.

If that is correct, then the “high wire act” of the Corwinesque relies on a kind of listening-for-risk that’s hard for us to do now, because we can’t listen to Corwin’s work new, or live. One deep aspect of the Corwinesque of the 1940’s – the possibility, even anticipation, of artistic failure, up above an enormous audience out there in the dark – seems lost for good.

Coalition and Collation

But in another way, the Corwinesque is only possible to grasp now, at the safe remove of the digital era. Today it’s easy to listen “distantly” to classic radio through formats that allow us to pause, rewind, categorize and remix vast amounts of golden age audio in a way that was impossible in 1947. By doing so it becomes clear that what we call the “Corwinesque” drew on a broad vocabulary of radio dramaturgy, a way of “talking about” time and space that characterized many programs of that time.

Consider Corwin’s famous attempts to glorify the “common man” – farmers, G.I.s, factory workers – by drawing their voices to a sonorous space and national coalition, indeed by making these two imaginary sites mirror and rationalize one another. Perhaps the paramount example is “We Hold These Truths,” which celebrated the 150th anniversary of the Bill of Rights only days after Pearl Harbor. In that broadcast, we hear Americans of the revolutionary period (widows, blacksmiths, politicians) speak from a series of shallow locations in a quick succession, and a similar group in the present (workers, Okies, businessmen, mothers), as a way of building mystical union through time.

A visual representation of the “kaleidosonic” from the 1939 broadcast “Americans All, Immigrants All”

This style has had many names. Historian Erik Barnouw likened it to painting, calling it a chance to “splash quickly over a large canvas,” while actor Joseph Julian called it a “telescoping montage.” Variety’s radio editor Bob Landry suggested that it resembled cantata. When I interviewed him, Corwin said that it was like writing music; elsewhere he spoke of a kind of “horizontal” drama, or mosaic form.

In my book, I employ another word: “kaleidosonic.” In kaleidosonic radio, we segue from place to place, experiencing shallow scenes as if from a series of fixed apertures, thereby giving time periods expressive existence. That can be contrasted with what I refer to as the “intimate style,” in which the listener is attached to a character who moves through deep scenes, as a way to give space expressive existence. A good example of the latter is Corwin’s American in England series, in which the horizon of wartime is shaped by a proximal relation to a surrogate narrating entity “nearby.” Here’s a representative episode:

Today, listening broadly, it becomes clear that neither of these styles belongs to Norman exclusively. For other uses of the kaleidosonic, consider the works of Stephen Vincent Benét, Orson Welles’ “The War of The Worlds” or Cavalcade of America. For examples of the “intimate style,” listen to Brewster Morgan’s “A Trip To Czardis,” or any “first-person” style play from The Mercury Theater on the Air. What made Corwin special was how he made these styles complimentary. The opening of “On a Note of Triumph” is a good example:

In six minutes, we go from a kaleidosonic sequence of songs and crowds to an ordinary G.I. overseas asking questions intimately. This connection between the context and the individual, between the nearby and the simultaneous, is Corwin’s way of letting space and time merge together vividly.

It is that capability, I contend, that underlies and secures Corwin’s glorification of the common man, who is really Corwin’s public aestheticized. In 1939, Archibald MacLeish wrote, “The situation of radio is the situation of poetry backwards. If poetry is an art without an audience, radio is an audience without an art.” Corwin intuited what MacLeish didn’t understand: in radio, the audience is the art.

And just as airing a coalition of voices was an epistemological act that reinvented those it depicted in 1945, our use of a new collation of recordings today redraws the parameters of what those sounds might mean, amplifying latencies, superficialities, and entwinings hitherto inaudible.

A Dead Sea Scroll

By 1947, Corwin’s dedication to the “little guy” was out of vogue. It seemed seditious to red-baiters, phony to leftists, and compromised to critics – The Nation’s Lou Frankel wrote of One World: “It is as if the late John Barrymore decided, without warning, to play Hamlet in pantomime.” On this point Hamburger’s profile pivots from hagiography to satire, including a series of goofy verses voiced by a “Chorus of One Hundred Little Guys from Everywhere in the World” and a grouchy monologue by the “Common Man,” complaining that Corwin talked past him, advising “you ought to think about what the words mean before you use them.”

Norman Corwin in 1947 (Credit: Los Angeles Times)

That reminds me of another coda, this one in Corwin’s 1944 play “Untitled.” The play concerns a dead soldier named Hank Peters, who speaks as he lies “fermenting in the wisdom of the earth.” The monologue concludes this way:

Death is a patriotic act, a metaphysical state, but also a restless moral energy bearing down on life, a thing standing in requirement of its vindicating narration. Perhaps this feature of the Corwinesque will ring especially true as classic radio continues to exist in its ongoing pseudo-immortality. Now that Corwin reposes in his own acre of undisputed ground and his voice circulates ghostlike in clouds of data, our question may be what ontological relation we ought to have with that voice, and those of other dead social visionaries, who really do keep on advising us after death, and will go on echoing after we’re gone.

But the Corwinesque isn’t just about how the dead “speak” to the living, long the ruling conceit in the theory of sound recording. It is also about another enigma: how the dead listen to us, an audience eavesdropping, in hiding, taking notes on an old scroll in a lost language.

—

Neil Verma is a Harper-Schmidt Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Chicago, where he teaches media aesthetics. Verma works on radio and its intersection with other media, and has taught subjects including film studies, sound, art history, literature, critical theory and intellectual history. His book, Theater of the Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics, and American Radio Drama, is published by the University of Chicago Press.

Trackbacks / Pingbacks