A Medieval Music Box: the Cantigas de Santa María as Sound Technology in the Age of Alfonso X

Each of the essays in this month’s “Medieval Sound” forum focuses on sound as it, according to Steve Goodman’s essay “The Ontology of Vibrational Force,” in The Sound Studies Reader, “comes to the rescue of thought rather than the inverse, forcing it to vibrate, loosening up its organized or petrified body (70). These investigations into medieval sound lend themselves to a variety of presentation methods loosening up the “petrified body” of academic presentation. Each essay challenges concepts of how to hear the Middle Ages and how the sounds of the Middle Ages continue to echo in our own soundscapes.

Each of the essays in this month’s “Medieval Sound” forum focuses on sound as it, according to Steve Goodman’s essay “The Ontology of Vibrational Force,” in The Sound Studies Reader, “comes to the rescue of thought rather than the inverse, forcing it to vibrate, loosening up its organized or petrified body (70). These investigations into medieval sound lend themselves to a variety of presentation methods loosening up the “petrified body” of academic presentation. Each essay challenges concepts of how to hear the Middle Ages and how the sounds of the Middle Ages continue to echo in our own soundscapes.

The posts in this series begins an ongoing conversation about medieval sound in Sounding Out!. Our opening gambit in April 2016, “Multimodality and Lyric Sound,” reframes how we consider the lyric from England to Spain, from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries, pushing ideas of openness, flexibility, and productive creativity. We will post several follow-ups throughout the rest of 2016 focusing on “Remediating Medieval Sound.” And, HEAR YE!, in April 2017, look for a second series on Aural Ecologies of noise! –Guest Editors Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

–

At a first glance, one might think the sounds of the Middles Ages unrecoverable from the fragmented yet abundant ruins of the past. The voices, noises, melodies seem lost to the present, casting the efforts to reconstruct matters of medieval sound as speculation. However, medieval peoples actually preserved copious traces of their efforts to produce the thing closest to contemporary sound recordings: comments, writings, treatises, music notation, verbal descriptions, music instruments and even architectural design in the name of sound. Testaments of such efforts– forgotten amplifiers resisting time’s erasure–appear in the form of one of the greatest and revolutionary accomplishments of the ten centuries comprising the Middle Ages: the development of the codex. Coupled with the meticulous treatment of writing, the codex ushered in a number of innovations slowly introduced in matters of script, binding, development of materials, the re-thinking of the function and design of the library, and others. During this expansive time, the topic of memory was linked to writing and its repositories as supportive instruments in an active way (Carruthers). Key to our discussion here, these developments greatly assisted melody, rhythm, the production of music in general, particularly through the slow creation of the written devices and symbols that eventually turned into music notation.

Alfonso X, King of Castile in the 13th century, set to participate in the stream of cultural reflections and productions about music and sound in the Middle Ages. One of his main works, the Cantigas de Santa María (sourced from here and here), is an awe-inspiring cultural monument, not only for its representation of monarchical values in Castile, but because it provides evidence of all of the efforts toward the careful attention to writing and music, and their links to matters of religious devotion. Among the topics carefully interwoven in the visual, written and musical registers of the Cantigas is a depiction of the culture of the kingdom of Castile and the Iberian Peninsula in the 13th century. Alfonso’s representations of Christians, Jews and Moors as part of the population affected by the presence and constant intervention of the Virgin sets his codices apart as unique examples of what some critics have proposed to see as the world of convivencia, a form of social organization in which collaboration and tolerance between peoples belonging to different cultural frames took place (Américo Castro).

A depiction of Alfonso’s scriptorium.

The Cantigas de Santa María is better defined as the cluster of four extant manuscripts, written in Galician-Portuguese, that display similar functions, design, topics, and organization (Fernández). As a whole, the Cantigas is the concerted effort to produce a body of materials for devotion to the Virgin Mary on behalf of King Alfonso, a multimedia, multidimensional, and a discursively multivalent groups of codices or manuscripts each organized in what John E. Keller calls the threefold method: lyrics/poetry, miniatures, and music notation. Of the extant codices, the Codex that is best known for being the most finished—as well as for the richness of the work of miniatures—is the Codex Rico, the basic codex from which I use examples in this article.

While there are plenty of critical comments and approaches to the Cantigas in terms of its poetic composition and content, as well as its miniatures or illustrations, the most puzzling element of its study remains its “sound.” There have been several efforts to analyze the music notation and tradition in the Cantigas from different viewpoints. Julián Ribera and Higinio Anglés, for example, attempted to produce a transcription of its music notation. Others, such as Hendrik van der Werf, made great efforts to analyze the particularities of the music notation and the interpretation of rhythm. However, musicologists maintain that we still need better working tools to interpret the music with full consideration of the information in the codices, as well as the points of contact and variations of music and lyrics from one of the codices to the other (Ferreira). As we work toward coordinating such a project, we still have several elements to work with to hear and interpret sound in the Cantigas.

To listen to the Cantigas, the reader/spectator/listener can begin by addressing the codices’ composition and construction. The texts not only offer a vast repertory of songs with music notation, but they also make use of miniatures to comment on the topics of sound and music. The codices are self-reflexive, which means that they make constant reference to their own construction and production. In this way, the texts challenge the reader/spectator/listener to consider the multiple layers of construction and meaning. For example, consider the definitions and views of sound and music exposed by the Cantigas. Here, the word “cantiga” is usually understood as either a song or short poem set to music, mostly about love, following the vocabulary of medieval courtly tradition (Parkinson). By the 12th century, the kingdoms to the north of the Iberian Peninsula had developed a lyrical form associated with courtly tradition known as the Cantigas d’amigo, written in Galician Portuguese, and linked to the troubadour tradition. The Cantigas appear to follow this tradition directly, suggesting the title references the form as well as the content of its lyrics. Therefore, the title Cantigas refers to the poetical conventions structuring the expression of devotion to a lady—most of the poems follow a particular structure of stanzas followed by a refrain—and it also signals the sound of such devotion.

A codex. Image borrowed from e-codices @Flickr CC BY-NC.

So how to describe the sound of the cantigas? What would the medieval reader/spectator of the codex understand just by looking at the music notation, poetic structures, illustrations and miracles about the role of sound, music, and voice as well?

For one thing, the miracles, miniatures or illustrations—as well as the music notation from one cantiga to the other—supply an excess of information. The codices present Jewish characters, heavy hints of the influence of Hispanic-Arabic poetic and music traditions (such as “rhythmic patterns from the muwashshah,” according to Manuel Pedro Ferreira, miracles from the Provençal tradition, Galician-Portuguese poetic structures and music, troubadour topics, the identification of melodies from secular traditions, profane music, and religious motifs. All of these together suggest that the reader/spectator/listener of the cantigas would have been expected to know at least a little of each of these elements.

The contemporary identification of these layers of information has led Cantigas scholars to hypothesize on the possible performance of its music. Research shows agreement on the folowing: the expression of clear melodic lines; the use of mensural notation (the system for European vocal polyphonic music used from the later part of the 13th century until about 1600); the interpretation of rhythm depending on the poetic structure and melodies of each poem; the use of melismas—runs of notes made from one syllable—and their function in performance; and the impossibility of interpreting the use of pitch. This last feature renders any attempt to reconstruct and perform the full range of the codices’ music virtually impossible. Any contemporary performance works as an exercise of imagination, an active effort to fill in the blanks of what may be described as an ambitious and extensive archive of and about music in the Iberian Peninsula of the 13th century.

Cantiga 8.

In the meantime, prospective listeners of the Cantigas’ music may still reflect on how it comments and represents the function of music and sound: from love and religious devotion, to entertainment, spiritual transformation. Its authors represent music as both skill and gift. Furthermore, as the following brief and striking examples show, many other sounds are encoded in the texts: voices, screams, streams, demands, prayer and cries. Cantiga 8 is about a Minstrel from Rocamadour who dedicates his songs to a statue of the Virgin Mary (fols. 15r-15v). He prays to her that she may give him a candle from the church. The Virgin is so pleased with his dedication that she makes a candle to rest on his “viola” (fiddle). A monk, unbelieving of the miracle, takes the candle away and accuses the minstrel of using magic. The miracle takes place for a second time, causing the monk to repent and join the minstrel and others in devotion. This may seem like a simple story of the values of faith communities, however the Cantigas underscores the role sound plays in devotion, through the minstrel’s voice and performance with his music instrument:

“que mui ben cantar sabía / e mui mellor vïolar ( fol. 15r, line 10).

(“…as he knew how to sing very well / and to fiddle even better”)

Moreover, the disbelieving monk is described as having understood his error as “aqueste miragre viu” (by “seeing” this miracle) and “entendeu que muit errara,” which may be translated as “understanding that he was in error.” However, in Portuguese, the verb “entender” (to understand) is also associated with the notion of understanding through auditory perception.

Cantiga 89.

Another example of the role of sound in Alfonso’s project is found in Cantiga 89 (fols. 130r-131r). This cantiga is about a Jewish woman who experiences a difficult childbirth. In the middle of the delivery of her baby, she hears a voice asking her to pray to the Virgin. As she moans and cries, she finds the strength to pray aloud to request the Virgin’s help. The poem stresses the quality of the sound of the laboring woman in the description of her suffering:

“Ela assi jazendo / que era mais morta ca viva / braadand’e gemendo/ echamando / sse mui cativa, / con tan gran door esquiva” (fol. 130v, lines 20-25).

(As she lay in this condition/ for she was more dead than alive / screaming and moaning / calling herself unfortunate / with great pain).

The Virgin helps the Jewish woman, who decides to convert to Christianity at the end of the cantiga. The text underscores the role of voice in both the spiritual intervention of the Virgin, but also in the human experience of pain and prayer.

Lastly, Cantiga 103, is about a monk who listened to a bird’s song for three hundred years (fols. 147v-148v). The monk asks the Virgin to let him glimpse paradise before dying. After hearing his prayer, however, the Virgin grants him not a view of paradise, but the sensation of its sounds:

“Tan toste que acababa ouv’o o mong’ a oraçon, / oyu ha passarinna cantar log’ en tan bon son, / que sse escaeceu seendo e catando sempr/ alá” ( fol. 148r, lines 23-25).

(“As soon as he finished his prayer / he heard a small bird sing with such a nice song / that he forgot about everything else remaining in the place forever”)

Three hundred years pass, and suddenly the monk remembers to return to his monastery. He finds everything there transformed. After telling his story, everyone shares the wonder of the miracle praising the Virgin. This text suggests a different appreciation of “paradise” not through the notion of “vision” but through aurality, the description of the spiritual well being as a sonic experience.

Cantiga 103.

This small sampling from cantigas underscores the value of voice, noise, and music as part of human experience, as central in the experience of religious devotion, and as transformative for the communities represented in the codices. King Alfonso strove to create a library containing all the knowledge available to his world. Additionally, he strove to participate actively in—and innovate—contemporary forms of knowledge production. In many ways, the Cantigas, function as a music box, its folios documenting multiple forms of sonic information, making available the experiences, values, soundscapes, and medieval ways of hearing/listening, or the aurality of the Middle Ages.

—

Featured image “girl laugh #10” by danor sutrazman @Flickr CC BY.

—

Marla Pagán-Mattos earned her doctorate in Comparative Literature and Literary Theory at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research interests include medieval literature, Iberian medieval history and literature, literary theory, and sound culture. She has taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Haverford College, and is currently teaching in the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of Puerto Rico.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Introduction: Medieval Sound–Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

“Playing the Medieval Lyric”: Remixing, Sampling and Remediating “Head Like a Hole” and “Call Me Maybe”–Dorothy Kim

Mouthing the Passion: Richard Rolle’s Soundscapes–Christopher Roman

“Playing the Medieval Lyric”: Remixing, Sampling and Remediating “Head Like a Hole” and “Call Me Maybe”

Each of the essays in this month’s “Medieval Sound” forum focuses on sound as it, according to Steve Goodman’s essay “The Ontology of Vibrational Force,” in The Sound Studies Reader, “comes to the rescue of thought rather than the inverse, forcing it to vibrate, loosening up its organized or petrified body (70). These investigations into medieval sound lend themselves to a variety of presentation methods loosening up the “petrified body” of academic presentation. Each essay challenges concepts of how to hear the Middle Ages and how the sounds of the Middle Ages continue to echo in our own soundscapes.

The posts in this series begins an ongoing conversation about medieval sound in Sounding Out!. Our opening gambit in April 2016, “Multimodality and Lyric Sound,” reframes how we consider the lyric from England to Spain, from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries, pushing ideas of openness, flexibility, and productive creativity. We will post several follow-ups throughout the rest of 2016 focusing on “Remediating Medieval Sound.” And, HEAR YE!, in April 2017, look for a second series on Aural Ecologies of noise! –Guest Editors Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

–

In 2013, a user named pomDeter posted a sound file on the social news and entertainment site Reddit that went viral in the form of YouTube videos, Facebook posts, and tweets: a mashup remediation of Nine Inch Nails’s “Head Like a Hole” with Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe.” Reactions ranged from outrage on the part of Nine Inch Nails’s drummer to declarations that it is a work of “genius” by the Los Angeles Times.

To understand the significance of this surprising piece of pop culture, we should recall that the iconic industrial rock anthem with sadomasochistic overtones “Head Like a Hole” is a track from NIN’s debut Pretty Hate Machine (1989), while “Call Me Maybe”–the title track to Jepsen’s eponymous first album—is a anthem about the exhilaration of a crush. Simply put, these two musical universes are not usually mentioned in the same breath, much less remixed into the same track. The result? “Call Me a Hole.”

The commentary about this musical clash of cultures has been vigorous and multi-sided. Listeners have unabashedly loved it, absolutely hated it, been very disturbed that they loved it, and been deeply distressed by what they see as the diluting of pure rock rage.

“Call Me a Hole” is a good example of both the theoretical underpinnings and the experimental possibilities of the issues at stake in my discussion of the medieval lyric. My post not only allows you to play the remix, but also to visualize the remixed song and read the second-by-second stream of commentary from a wide range of listeners. In this way, this remediated, multimodal, multimedia moment perfectly encapsulates the possibilities of experimentation, the participatory culture of multimodal productions, and the simultaneous discomfort and seduction these experimental remixings may engender. The commentary on Soundcloud is a perfect record of all these things: this cultural production is “awesome, creepy, bittersweet, disturbing, strange, brilliant, genius.”

“Playing the Medieval English Lyric” briefly examines the emergence of the lyric form in 13th-century miscellanies—an emergence that, in many ways, mirrors the development of mashups like “Call Me a Hole.” This work dovetails with larger critical issues apparent in deeply examining the material culture of miscellanies—medieval anthologies—how they were made, their quire formations, their marginalia, their scribes, their audiences. But I juxtapose this investigation with the insights of more recent theoretical ideas about multimodality, remediation, and mashup. Both recent digital rhetoric and medieval rhetorical theory can help us think through the place of music in the emergence of new literary genres and contextualize the creation of new technologies of sound.

Image by Richard Smith @Flickr CC BY.

The mashup as a new musical genre especially dependent on the affordances of a digital platform transforms the place of the audience from mere “consumer” to “producer,” according to Ragnhild Brøvig-Hanssen’s entry “Justin Bieber Featuring Slipknot: Consumption as Mode of Production,” in The Oxford Handbook of Music and Virtuality (268). Mashups also switch the relation of the producers/composers of music into the role of consumers/listeners. Brøvig-Hanssen goes on to argue that “it is often [mashup’s] experiential doubling of the music as simultaneously congruent (sonically, it sounds like a band performing together) and incongruent (it periodically subverts socially constructed conceptions of identities) that produces the richness in meaning and paradoxical effects of successful mashups (270).

These incongruent, yet congruent juxtapositions that produce rich meaning also form the pattern I see in the emergence of medieval English lyric. In essence, I hope to show how a discussion about digital mashups in today’s musical ecosystem can help us reframe the emergence of the medieval lyric in 13th-century medieval Britain. How do different media platforms—manuscript and digital—spur on certain parallel forms of sonic media play and creativity?

In particular, I am interested in how the sampling, mixing, and palimpsestic juxtaposition of mixed-language manuscripts (usually including Latin, Anglo-Norman French, and Middle English) have created a space for new linguistic and sonic remixes and new genres to play and form. In this article, I reconsider the (really) “old” media of the manuscript page as a recording and playing interface existing at a particularly dynamic juncture when new experimental forms abound for the emergence, revision, and recombination of literary oeuvres, genres, and technologies of sound.

Multilingualism and the Medieval English Lyric Scene

Image used for purposes of critique.

Just as a screen shot of the “Call Me a Hole” website would preserve in static form such external references as links to articles discussing the mashup (and would allow future readers to add new information), I similarly argue that a medieval manuscript page has creative, annotated possibilities that stop it from being a fixed, “literate” page. Readers throughout the centuries may add marginal notes, make annotations, cross out sections, or add new sections. More visually-oriented readers may include marginal drawings, even going so far as to animate narratives by drawing a series of connected images or to add interactive features like flaps, or rotae. If the manuscript page in question includes lyrics, notes, or both, it may have served as the inspiration for a wide variety of dramatic or musical performances, whether public or private. Finally, the physical book itself may have been broken apart, recombined with other books, or reused as endpapers for other books. In this way, I advocate for an understanding of the manuscript medium as a dynamic media zone like the digital screen. The manuscript page is thus, a mise-en-système: a dynamic reading/recording interface.

Much of the vernacular English literary production in the 13th and into the first half of the 14th century is preserved in multilingual manuscripts. I think Tim Machan said it best at 2008’s Multilingualism in the Middle Ages conference, particularly in situating Middle English in England, when he talks about “the ordinariness of multilingualism” and how much it is “the background noise” in the Middle Ages in Britain. The thirteenth-century multilingual matrix included verbal and written forms of the following languages: Old English, Middle English, Latin, Greek, Anglo-Norman French, Continental French, Irish, Welsh, Cornish, Hebrew, Flemish, and Arabic. If multilingualism is the background noise, then it’s a background concert in which all those linguistic sounds perform simultaneously. The medieval manuscript’s ocularcentrism has given readers visual cues, but the cues ask us to remix, reinterpret, and reinvent the materials. They do not ask us to just see these signs—whether music, art, text—as separate, hermetically sealed universes working as solo acts.

Intersecting this active ferment was the creative flux and reinvention of English musical notation and distinctly regional styles. These forces, I believe, helped create an experimental dynamism that may explain what the manuscript record reveals about the emergence of the Middle English lyric. The notation of Western music as we now understand it, which would begin to emerge in the 9th century, focused heavily on religious music, on chant. And Latin chant can be syllabically texted to any music. Likewise, Anglo-Norman French poetry focused on a form using syllable counts—octasyllabic couplets. This poetic form also was easily translated into Western musical notation. What, however, do you do with English poetry that is alliterative or uses another kind of stressed poetic meter? These problems are, in fact, probably why it took some time for Middle English to produce lyrics that were texted to music.

Image by Juanedc @Flickr CC BY.

Another reason for this phenomenon lies with the state of musical notation itself. In the entry on “musical notation” in the New Grove Dictionary of Music (http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/public/book/omo_gmo), an entire history of the creation of musical notation in the Middle Ages—and specifically its experimental and regional varieties—are mapped out. In addition, Carl Parrish’s classic text, The Notation of Medieval Music, a standard in all musical paleography classes, shows the minute shifts in the construction of medieval music from century to century and from region to region. And finally, the development of the stave line as “new technology” would spur further writing of music “without additional aural support.” What these histories of medieval musical notation have in common is their emphasis on the constantly shifting paradigms that this new technology of writing to record sound showed across different regions and different centuries.

From the second quarter of the 13th century to the mid-14th century, a number of multilingual miscellanies have survived, preserving an astonishing breadth of poetic work in Latin, Middle English, and Anglo-Norman French. These books circulated in relation to each other and in conversation with each other and were collected and compiled in miscellanies. There are a fair number of multilingual miscellanies that contain a range of lyrical poetry in Middle English and Anglo-Norman French. My list here is not exhaustive, but I would like to point to a few (pulled from Laing and Deeming’s work) that we will discuss: Oxford, Jesus College MS 29; Oxford, Bodleian library MS Digby 86; London, British Library MS Arundel 248; London, British Library MS Egerton 613; London, British Library MS Egerton 2253; London, British Library MS Harley 978; Kent, Maidstone Museum A. 13; Cambridge, St. John’s College MS E.8; London, British Library MS Royal 12 E.i; Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson G18.

With the exception of the criticism of Harley 978, the manuscript containing the famous “summer canon,” which only contains one piece of Middle English poetry, the scholarly discussion of the miscellanies’ lyrics rarely touches on music (with the notable exception of Helen Deeming’s assiduous work). This critical silence is particularly disconcerting because several of these manuscripts either have notes or signs of music in them, or their lyrical texts have music attached to them in other manuscripts. What I would like to propose, then, is a narrow sampling that will give us a wider picture of what the lyrical record may reveal.

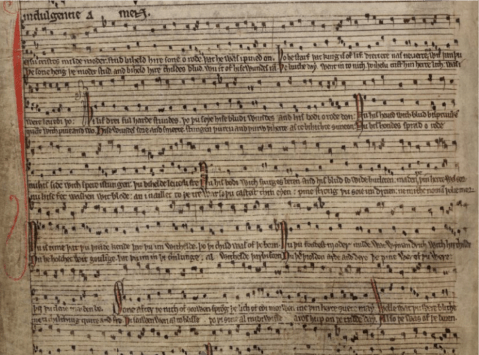

Poetic and Musical Samplings of the Lyric Page

The manuscript layouts of a sample of these medieval multilingual musical miscellanies reveal how musical notes and letters were, at times, considered in the same category. The mise-en-système of these manuscripts also reveal the fluidity, creativity, and cues for audience/listener/reader’s (including the scribal compiler) ability to mashup the multilingual musical matrix. In the manuscript Arundel 248, music is attached to the lyrics, but it is laid out in quite an unusual way. Arundel 248 contains mostly Latin religious texts, including several tracts on sin. However, near the end, there are several lyrical texts that also appear in Digby 86; Jesus 29; and Rawlinson G. 18. On f. 154r, the entire page has Latin, Anglo-Norman, and English verse texted to music. What is interesting about this page, especially in comparison to other musical pages in the MS and the standard layout of thirteenth-century English music, is the folio’s mise-en-page. The scribe has literally laid out a series of lines (particularly in the top half) that then places English poetry, Anglo-Norman French poetry, and Latin poetry with English musical notation. The lack of specific stave lines (though they appear in other parts of this manuscript and at the bottom of this folio) means that the technology of this particular form of sound recording has allowed all these different things—English musical notes, English vernacular notation, Latin notation, and Anglo-Norman vernacular notation—equal space and play. They all have been squeezed onto these black ruled lines (at the top). The mise-en-page, then, allows linguistic differences to be on par with differences in sonic styles. What this manuscript ultimately creates is a miscellany of sound.

The page’s layout cues a sonic palimpsest—or, in contemporary terms, a sonic mash-up—and suggests potentially simultaneous performance. In fact, this vocal performance becomes even more complex in the next slide, f. 154v, because the texted English lyric is a polyphonic piece that also, in many of its manuscripts, has Latin lyrics. This is “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder,” (DIMEV 2831 http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=2831) which comes with English lyrics and texted music. It appears to be a version of “Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem,” though the standard version with music appears in St. John’s College, MS E.8 with the standard English lyrics underneath the melody (DIMEV 5030 http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=5030 ). The latter English lyric connected to “Stabat Iuxta” is “Stand wel moder” and there are several versions of the lyric without music—Digby 86, Harley 2253, Royal 8 F.ii, Trinity College, MS Dublin 301. Another manuscript, Royal MS 12 E.i, contains the same music for “Stand wel moder.” Deeming has noted that the lyrics of this version, “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” correspond closely to “Stabat Iuxta” and could be sung with the standard melody (as seen in Royal 8 F.ii) as a contrafactum. However, you can do a mashup of “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” and its accompanying music juxtaposed with the text and music of “Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem.” As an experiment, I had Camerata, the early Music Group at Vassar College, record this piece, “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” from Arundel 248 with the musical version of “Stabat Iuxta” from St. John’s College MS E.8 (Found in Deeming’s Songs in British Sources (196, 201, 210-211). Other than direction on how to pronounce Middle English (as well as the accompanying contemporary editions of each lyric), I left the performance details to the group themselves to figure out. This is what they recorded – this is the medieval mashup.

The performance shows the creative possibilities of the page, and how music is a very distinct kind of sound player. What song—and particularly multi-part song—has done, is to generate sonic harmony out of linguistic babel. There is a pattern of circulation that intertwines music (both monophony and polyphony) with multilingual lyrics, and this manuscript especially demonstrates those sonic possibilities. These pages demonstrate a diverse soundscape that records and imagines an interesting multimedia and multilingual voice at play. In essence, Arundel 248 displays the different possibilities a reader could have in switching between or layering different modes of sound.

“Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem.” London, British Library MS Arundel 248, f. 154v.

—

Featured image “staff” by Arko Sen @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND

—

Dorothy Kim is an Assistant Professor of English at Vassar College. She is a medievalist, digital humanist, and feminist. She has been a Fulbright Fellow, a Ford Foundation Fellow, a Frankel Fellow at the University of Michigan. She has been awarded grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Mellon Foundation. She is a Korean American who grew up in Los Angeles in and around Koreatown.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Blue Notes of Sampling–Primus Luta

Remixing Girl Talk: The Poetics and Aesthetics of Mashups–Aram Sinnreich

A Tribe Called Red Remixes Sonic Stereotypes–Christina Giacona

Recent Comments