Sounding Out! Podcast X!: Blog-o-Versary 10.0

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD: X!

SUBSCRIBE TO THE SERIES VIA ITUNES

ADD OUR PODCASTS TO YOUR STITCHER FAVORITES PLAYLIST

X!

Priests, “Texas Instruments”—THE EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE

Government Cheese, “Fish Stick Day”—Kevin Archer

Princess Nokia, “Brujas”—Reina Prado

Sammus, “Mighty Morphing”—Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo

Lucreccia Quintanilla, “Como Mujer (Ivy Queen+General Feelings+NaRemix)—Lucreccia Quintanilla

LSD, feat. Sia, Diplo, and Labrinth, “Genius”—Kaitlyn Liu

The Beths, “Future Me Hates Me”—James Tlsty

Fever Ray, “To The Moon and Back”—Airek Beauchamp

Solange, “Binz”—Liana Silva

Ghostface Killah, “9 Milli”—Rob Ryan

Sly & the Family Stone, “Thankful & Thoughtful”—Walter Gershon

Conan Osiris, “Telemoveis”—Carlo Patrão

Beyoncé, feat. Kendrick Lamar, “Freedom”—Jenna Perez

Lizzo, “Tempo”—Jennifer Lynn Stoever

Brother Ali, “Own Light (What Hearts Are For)”—Phillip Sintiere

Holly Herndon, “Frontier”—John Melillo

X-Ray Spex, “Identity”—Aaron Trammell

Mitski, “Washing Machine Heart”—Kelly Hiser

Meridian, “A Fire in the City”—Julie Beth Napolin

D-Lite, “Groove Is In The Heart”—Eddy Alvarez

Drake, “Started from the Bottom”—Kristin Leigh Moriah

—

***Click here to read our Blog-o-versary year-in-review by Ed. in Chief JS

Share this:

In Search of Politics Itself, or What We Mean When We Say Music (and Music Writing) is “Too Political”

Music has become too political—this is what some observers said about the recent Grammy Awards. Following the broadcast last week, some argued that musicians and celebrities used the event as a platform for their own purposes, detracting from the occasion: celebration of music itself. Nikki Haley, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, tweeted:

I have always loved the Grammys but to have artists read the Fire and Fury book killed it. Don’t ruin great music with trash. Some of us love music without the politics thrown in it.— Nikki Haley (@nikkihaley) January 29, 2018

I don’t know for sure, but I imagine that the daily grind of a U.N. ambassador is filled with routine realities we refer to as “politics”: bureaucracy, budget planning, hectic meetings, and all kinds of disagreements. It makes some sense to me, then, that Haley would demand a realm of life that is untouched by politics—but why music in particular?

The fantasy of a space free from politics resembles other patterns of utopian thought, which often take the form of nostalgia. “There was a time when only a handful of people seemed to write politically about music,” said Chuck Klosterman, a novelist and critic of pop culture, in an interview in June 2017. He continued:

Now everybody does, so it’s never interesting. Now, to see someone only write about the music itself is refreshing. It’s not that I don’t think music writing should have a political aspect to it, but when it just becomes a way that everyone does something, you see a lot of people forcing ideas upon art that actually detracts [sic] from the appreciation of that art. It’s never been worse than it is now.

He closed his interview by saying: “I do wonder if in 15 years people are going to look back at the art from this specific period and almost discover it in a completely new way because they’ll actually be consuming the content as opposed to figuring out how it could be made into a political idea.” Klosterman almost said it: make criticism great again.

Reminiscing about a time when music writing was free from politics, Klosterman suggests that critics can distinguish between pure content and mere politics—which is to say, whatever is incidental to the music, rather than central to it. He offers an example, saying, “My appreciation of [Merle Haggard’s] ‘Workin’ Man Blues’ is not really any kind of extension of my life, or my experience, or even my values. […] I can’t describe why I like this song, I just like it.” If Klosterman, an accomplished critic, tried to describe the experiences that lead him to like this particular song, he probably could—but the point is that he doesn’t make explicit the relationship between personal identity and musical taste.

Screen Capture of Merle Haggard singing “Workin’ Man Blues,” Live from Austin, Texas, 1978

The heart of Klosterman’s concern is that critics project too many of their own problems and interests onto musicians. Musician and music writer Greg Tate recently made a similar suggestion: when reviewing Jay-Z’s album 4:44, Tate focuses on how celebrities become attached to public affects. In his July 2017 review, “The Politicization of Jay-Z,” he writes:

In the rudderless free fall of this post-Obama void […] all eyes being on Bey-Z, Kendrick, and Solange makes perfect agitpop sense. All four have become our default stand-ins until the next grassroots groundswell […] Bey-Z in particular have become the ready-made meme targets of everything our online punditry considers positive or abhorrent about Blackfolk in the 21st century.

Jay and Bey perform live in 2013, by Flickr user sashimomura,(CC BY 2.0)

He suggests that critics politicize musicians, turning them into repositories of various projections about the culture-at-large. Although writing from a very different place than Klosterman, Tate shares the sense that most music criticism is not really about music at all. But whereas Klosterman implies that criticism resembles ideological propaganda too much, Tate implies that criticism is a mere “stand-in” for actual politics, written at the expense of actual political organizing. In other words, music criticism is not political enough.

In 1926, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about this problem, the status of art as politics. In his essay “Criteria of Negro Art,” he dissects what he perceives to be the hypocrisy of any demand for pure art, abstracted from politics; he defends art that many others would dismiss as propagandistic—a dismissal revealed to be highly racialized. He writes:

Thus all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda. But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.

Du Bois’s ideas would be engaged extensively by later authors, including Amiri Baraka. In his 1963 essay “Jazz and the White Critic,” he addresses politics in terms of “attitude.” Then-contemporary white critics misunderstood black styles, he argued, because they failed to fully apprehend the attitudes that produced them. They were busy trying, and failing, to appreciate the sound of bebop “itself,” but without considering why bebop was made in the first place.

Dizzy Gillespie, one of BeBop’s key players, in Paris, 1952, Image courtesy of Flickr User Kristen, (CC BY 2.0)

As Baraka presents it, white critics were only able to ignore black musicians’ politics and focus on the music because the white critics’ own attitudes had already been assumed to be superior, and therefore rendered irrelevant. Only because their middle-brow identities had been so thoroughly elevated in history could these middle-brow critics get away with defining the object of their appreciation as “pure” music. Interestingly, as Baraka concludes, it was their ignorance of context that ultimately served to “obfuscate what has been happening with the music itself.” It’s not that the music itself doesn’t matter; it’s that music’s context makes it matter.

In response to morerecent concerns about the politicization of popular music, Robin James has analyzed the case of Beyoncé’s Lemonade. She performs a close reading of two reviews, by Carl Wilson and by Kevin Fallon, both of whom expressly seek the album’s “music itself,” writing against the many critical approaches that politicize it. James suggests that these critics can appeal to “music itself” only because their own identities have been falsely universalized and made invisible. They try to divorce music from politics precisely because this approach, in her words, “lets white men pop critics have authority over black feminist music,” a quest for authority that James considers a form of epistemic violence.

That said, James goes on to conclude that the question these critics ask—“what about the music?”—can also be a helpful starting point, from which we can start to make explicit some types of knowledge that have previously remained latent. The mere presence of the desire for a space free from politics and identity, however problematic, tells us something important.

Our contemporary curiosity about identity—identity being our metonym for “politics” more broadly—extends back at least to the 1990s, when music’s political status was widely debated in terms of it. For example, in a 1991 issue of the queercore zine Outpunk, editor Matt Wobensmith describes what he perceived to be limitations of thinking about music within his scene. He laments what he calls “musical purism,” a simplistic mindset by which “you are what you listen to.” Here, he capitalizes his points of tension:

Our contemporary curiosity about identity—identity being our metonym for “politics” more broadly—extends back at least to the 1990s, when music’s political status was widely debated in terms of it. For example, in a 1991 issue of the queercore zine Outpunk, editor Matt Wobensmith describes what he perceived to be limitations of thinking about music within his scene. He laments what he calls “musical purism,” a simplistic mindset by which “you are what you listen to.” Here, he capitalizes his points of tension:

Suddenly, your taste in music equates you with working class politics and a movement of the disenfranchised. Your IDENTITY is based on how music SOUNDS. How odd that people equate musical chops with how tough or revolutionary you may be! Music is a powerful language of its own. But the music-as-identity idea is a complete fiction. It makes no sense and it defies logic. Will someone please debunk this myth?

Wobensmith suggests that a person’s “musical chops,” their technical skills, have little to do with their personal identity. Working from the intersection of Klosterman and Tate, Wobensmith imagines a scenario in which the abstract language of music transcends the identities of the people who make it. Like them, Wobensmith seems worried that musical judgments too often unfold as critiques of a musician’s personality or character, rather than their work. Critics project themselves onto music, and listeners also get defined by the music they like, which he finds unsettling.

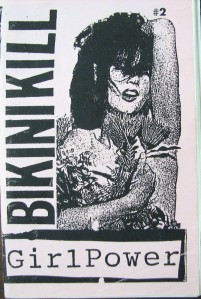

That same year, in an interview published in the 1991 issue of the zine Bikini Kill, musicians Kathleen Hanna and Jean Smith addressed a similar binary as Wobensmith, that of content and technique. But they take a different view: in fact, they emphasize the fallacy of this dualism in the first place. “You just can’t separate it out,” said Hanna, questioning the possibility of distinguishing between content—the “music itself”—and technique on audio recordings.

That same year, in an interview published in the 1991 issue of the zine Bikini Kill, musicians Kathleen Hanna and Jean Smith addressed a similar binary as Wobensmith, that of content and technique. But they take a different view: in fact, they emphasize the fallacy of this dualism in the first place. “You just can’t separate it out,” said Hanna, questioning the possibility of distinguishing between content—the “music itself”—and technique on audio recordings.

Female-fronted bands of this era were sometimes criticized for their lack of technique, even as terrible male punk bands were widely admired for their cavalier disregard of musical rules. Further still, disparagement of women’s poor technique often overlooked the reasons why it suffered: many women had been systematically discouraged from musical participation in these scenes. Either way, as Tamra Lucid has argued, it is the enforcement of “specific canons of theory and technique,” inevitably along the lines of identity, that cause harm if left unexamined.

All of these thinkers show that various binaries in circulation—sound and identity, personality and technique, music and politics—are gendered in insidious ways, an observation arrived at by the same logic that led Du Bois to reveal the moniker of “propaganda” to be racialized. As Hanna puts it, too many people assumed that “male artists are gonna place more importance on technique and female artists’ll place more on content.” She insists that these two concepts can’t be separated in order to elevate aspects of experience that had been implicitly degraded as feminine: the expression of righteous anger, or recollection of awkward intimacy.

Bikini Kill at Gilman Street, Berkeley, CA, 1990s, Image by Flickr User John Eikleberry, CC BY-NC 2.0

Punk had never pretended not to be political, making it a powerful site for internal critique. Since the 1970s, punk had been a form in which grievances about systemic problems and social inequality could be openly, overtly aired. The riot grrrls, by politicizing confessional, femme, and deeply private forms of expression within punk, demonstrated that even the purest musical politics resemble art more than is sometimes thought: “politics itself” is necessarily performative, personal, and highly expressive, involving artifice.

Even the act of playing music can be considered a form of political action, regardless of how critics interpret it. In another punk zine from c. 1990, for example, an anonymous author asks:

What impact can music have? You could say that it’s always political, because a really good pop song, even when it hasn’t got political words, is always about how much human beings can do with the little bag of resources, the limited set of playing pieces and moves and words, available […] Greil Marcus calls it ‘the vanity of believing that cheap music is potent enough to take on nothingness,’ and it may be cool in some places to mock him but here he’s dead-on right.

But music is never only political—that is, not in the elections-and-petitions sense of the word. And music is always an action, always something done to listeners, by musicians (singers, songwriters, producers, hissy stereo systems)—but it’s never only that, when it’s any good: no more than you, reader, are the social roles you play.

The author persuades us that music is political, even as they insist that it’s something more. Music as “pure sound,” as a “universal language” seems to have the most potential to be political, but also to transcend politics’ limitations—the trash, the propaganda. Given this potential, some listeners find themselves frustrated with music’s consistent failure to rise to their occasion, to give them what they desire: to be apolitical.

Kelly Clarkson performed at The Chelsea on July 27, 2012, image by Flickr User The Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas, CC BY-NC 2.0

In an interview during the recent Grammys broadcast, pop singer Kelly Clarkson said, “I’m political when I feel like I need to be.” It’s refreshing to imagine politics this way, like a light we turn on and off–and it’s a sign of political privilege to be able to do so. But politics are, unfortunately, inextricable from our lives and therefore inescapable: the places we go, the exchanges we pursue, the relationships we develop, the ways we can be in the world. Thinking with Robin James, it seems that our collective desire for a world free from all this reveals a deeper knowledge, which music helps make explicit: we wish things were different.

I wonder if those who lament the “contamination” of the Grammys with politics might be concerned that their own politics are unfounded or irrelevant, requiring revision, just as many white people who are allergic to identity politics are, in fact, aware that our own identity has been, and continues to be, unduly elevated. When Chuck Klosterman refuses to describe the reason why he likes “Workin’ Man Blues,” claiming that he “just does,” does he fear, as I sometimes do, not that there is no reason, but that this reason isn’t good enough?

Fortunately, there are many critics today who do the difficult work of examining music’s politics. Take Liz Pelly, for example, whose research about the backend of streaming playlists reminds us of music’s material basis. Or what about the astute criticism of Tim Barker, Judy Berman, Shuja Haider, Max Nelson, and others for whom musical thought and action are so thoroughly intertwined? Finally, I think of many music writers at Tiny Mix Tapes, such as Frank Falisi, Hydroyoga, C Monster, or Cookcook, for whom creation is a way of life—and whose creative practices themselves are potent enough to “take on nothingness.”

“Music is never only political,” as the anonymous ‘zine article author argues above, but it is always political, at least a little bit. As musicians and critics, our endeavor should not be to transcend this fact, but to affirm it with increasing nuance and care. During a recent lecture, Alexander Weheliye challenged us in a lecture given in January 2018 at New York University, when listening, “To really think: what does this art reflect?” Call it music or call it politics: the best of both will change somebody’s mind for real, and for the better.

—

Featured Image: Screen Capture from Kendrick Lamar’s video for “HUMBLE,” winner of the 2018 Grammy for “Best Music Video.”

—

Elizabeth Newton is a doctoral candidate in musicology. She has written for The New Inquiry, Tiny Mix Tapes, Real Life Magazine, the Quietus, and Leonardo Music Journal. Her research interests include musico-poetics, fidelity and reproduction, and affective histories of musical media. Her dissertation, in progress, is about “affective fidelity” in audio and print culture of the 1990s.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Reads: Jace Clayton’s Uproot–Elizabeth Newton

Re: Chuck Klosterman – “Tomorrow Rarely Knows”–Aaron Trammell

This is What It Sounds Like . . . . . . . . On Prince (1958-2016) and Interpretive Freedom–Ben Tausig

Share this:

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Rhetoric After Sound: Stories of Encountering “The Hum” Phenomenon

- Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions

- Wingsong: Restricting Sound Access to Spotted Owl Recordings

- Listening Together/Apart: Intimacy and Affective World-Building in Pandemic Digital Archival Sound Projects

- The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments