“Playing the Medieval Lyric”: Remixing, Sampling and Remediating “Head Like a Hole” and “Call Me Maybe”

Each of the essays in this month’s “Medieval Sound” forum focuses on sound as it, according to Steve Goodman’s essay “The Ontology of Vibrational Force,” in The Sound Studies Reader, “comes to the rescue of thought rather than the inverse, forcing it to vibrate, loosening up its organized or petrified body (70). These investigations into medieval sound lend themselves to a variety of presentation methods loosening up the “petrified body” of academic presentation. Each essay challenges concepts of how to hear the Middle Ages and how the sounds of the Middle Ages continue to echo in our own soundscapes.

The posts in this series begins an ongoing conversation about medieval sound in Sounding Out!. Our opening gambit in April 2016, “Multimodality and Lyric Sound,” reframes how we consider the lyric from England to Spain, from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries, pushing ideas of openness, flexibility, and productive creativity. We will post several follow-ups throughout the rest of 2016 focusing on “Remediating Medieval Sound.” And, HEAR YE!, in April 2017, look for a second series on Aural Ecologies of noise! –Guest Editors Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

–

In 2013, a user named pomDeter posted a sound file on the social news and entertainment site Reddit that went viral in the form of YouTube videos, Facebook posts, and tweets: a mashup remediation of Nine Inch Nails’s “Head Like a Hole” with Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe.” Reactions ranged from outrage on the part of Nine Inch Nails’s drummer to declarations that it is a work of “genius” by the Los Angeles Times.

To understand the significance of this surprising piece of pop culture, we should recall that the iconic industrial rock anthem with sadomasochistic overtones “Head Like a Hole” is a track from NIN’s debut Pretty Hate Machine (1989), while “Call Me Maybe”–the title track to Jepsen’s eponymous first album—is a anthem about the exhilaration of a crush. Simply put, these two musical universes are not usually mentioned in the same breath, much less remixed into the same track. The result? “Call Me a Hole.”

The commentary about this musical clash of cultures has been vigorous and multi-sided. Listeners have unabashedly loved it, absolutely hated it, been very disturbed that they loved it, and been deeply distressed by what they see as the diluting of pure rock rage.

“Call Me a Hole” is a good example of both the theoretical underpinnings and the experimental possibilities of the issues at stake in my discussion of the medieval lyric. My post not only allows you to play the remix, but also to visualize the remixed song and read the second-by-second stream of commentary from a wide range of listeners. In this way, this remediated, multimodal, multimedia moment perfectly encapsulates the possibilities of experimentation, the participatory culture of multimodal productions, and the simultaneous discomfort and seduction these experimental remixings may engender. The commentary on Soundcloud is a perfect record of all these things: this cultural production is “awesome, creepy, bittersweet, disturbing, strange, brilliant, genius.”

“Playing the Medieval English Lyric” briefly examines the emergence of the lyric form in 13th-century miscellanies—an emergence that, in many ways, mirrors the development of mashups like “Call Me a Hole.” This work dovetails with larger critical issues apparent in deeply examining the material culture of miscellanies—medieval anthologies—how they were made, their quire formations, their marginalia, their scribes, their audiences. But I juxtapose this investigation with the insights of more recent theoretical ideas about multimodality, remediation, and mashup. Both recent digital rhetoric and medieval rhetorical theory can help us think through the place of music in the emergence of new literary genres and contextualize the creation of new technologies of sound.

Image by Richard Smith @Flickr CC BY.

The mashup as a new musical genre especially dependent on the affordances of a digital platform transforms the place of the audience from mere “consumer” to “producer,” according to Ragnhild Brøvig-Hanssen’s entry “Justin Bieber Featuring Slipknot: Consumption as Mode of Production,” in The Oxford Handbook of Music and Virtuality (268). Mashups also switch the relation of the producers/composers of music into the role of consumers/listeners. Brøvig-Hanssen goes on to argue that “it is often [mashup’s] experiential doubling of the music as simultaneously congruent (sonically, it sounds like a band performing together) and incongruent (it periodically subverts socially constructed conceptions of identities) that produces the richness in meaning and paradoxical effects of successful mashups (270).

These incongruent, yet congruent juxtapositions that produce rich meaning also form the pattern I see in the emergence of medieval English lyric. In essence, I hope to show how a discussion about digital mashups in today’s musical ecosystem can help us reframe the emergence of the medieval lyric in 13th-century medieval Britain. How do different media platforms—manuscript and digital—spur on certain parallel forms of sonic media play and creativity?

In particular, I am interested in how the sampling, mixing, and palimpsestic juxtaposition of mixed-language manuscripts (usually including Latin, Anglo-Norman French, and Middle English) have created a space for new linguistic and sonic remixes and new genres to play and form. In this article, I reconsider the (really) “old” media of the manuscript page as a recording and playing interface existing at a particularly dynamic juncture when new experimental forms abound for the emergence, revision, and recombination of literary oeuvres, genres, and technologies of sound.

Multilingualism and the Medieval English Lyric Scene

Image used for purposes of critique.

Just as a screen shot of the “Call Me a Hole” website would preserve in static form such external references as links to articles discussing the mashup (and would allow future readers to add new information), I similarly argue that a medieval manuscript page has creative, annotated possibilities that stop it from being a fixed, “literate” page. Readers throughout the centuries may add marginal notes, make annotations, cross out sections, or add new sections. More visually-oriented readers may include marginal drawings, even going so far as to animate narratives by drawing a series of connected images or to add interactive features like flaps, or rotae. If the manuscript page in question includes lyrics, notes, or both, it may have served as the inspiration for a wide variety of dramatic or musical performances, whether public or private. Finally, the physical book itself may have been broken apart, recombined with other books, or reused as endpapers for other books. In this way, I advocate for an understanding of the manuscript medium as a dynamic media zone like the digital screen. The manuscript page is thus, a mise-en-système: a dynamic reading/recording interface.

Much of the vernacular English literary production in the 13th and into the first half of the 14th century is preserved in multilingual manuscripts. I think Tim Machan said it best at 2008’s Multilingualism in the Middle Ages conference, particularly in situating Middle English in England, when he talks about “the ordinariness of multilingualism” and how much it is “the background noise” in the Middle Ages in Britain. The thirteenth-century multilingual matrix included verbal and written forms of the following languages: Old English, Middle English, Latin, Greek, Anglo-Norman French, Continental French, Irish, Welsh, Cornish, Hebrew, Flemish, and Arabic. If multilingualism is the background noise, then it’s a background concert in which all those linguistic sounds perform simultaneously. The medieval manuscript’s ocularcentrism has given readers visual cues, but the cues ask us to remix, reinterpret, and reinvent the materials. They do not ask us to just see these signs—whether music, art, text—as separate, hermetically sealed universes working as solo acts.

Intersecting this active ferment was the creative flux and reinvention of English musical notation and distinctly regional styles. These forces, I believe, helped create an experimental dynamism that may explain what the manuscript record reveals about the emergence of the Middle English lyric. The notation of Western music as we now understand it, which would begin to emerge in the 9th century, focused heavily on religious music, on chant. And Latin chant can be syllabically texted to any music. Likewise, Anglo-Norman French poetry focused on a form using syllable counts—octasyllabic couplets. This poetic form also was easily translated into Western musical notation. What, however, do you do with English poetry that is alliterative or uses another kind of stressed poetic meter? These problems are, in fact, probably why it took some time for Middle English to produce lyrics that were texted to music.

Image by Juanedc @Flickr CC BY.

Another reason for this phenomenon lies with the state of musical notation itself. In the entry on “musical notation” in the New Grove Dictionary of Music (http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/public/book/omo_gmo), an entire history of the creation of musical notation in the Middle Ages—and specifically its experimental and regional varieties—are mapped out. In addition, Carl Parrish’s classic text, The Notation of Medieval Music, a standard in all musical paleography classes, shows the minute shifts in the construction of medieval music from century to century and from region to region. And finally, the development of the stave line as “new technology” would spur further writing of music “without additional aural support.” What these histories of medieval musical notation have in common is their emphasis on the constantly shifting paradigms that this new technology of writing to record sound showed across different regions and different centuries.

From the second quarter of the 13th century to the mid-14th century, a number of multilingual miscellanies have survived, preserving an astonishing breadth of poetic work in Latin, Middle English, and Anglo-Norman French. These books circulated in relation to each other and in conversation with each other and were collected and compiled in miscellanies. There are a fair number of multilingual miscellanies that contain a range of lyrical poetry in Middle English and Anglo-Norman French. My list here is not exhaustive, but I would like to point to a few (pulled from Laing and Deeming’s work) that we will discuss: Oxford, Jesus College MS 29; Oxford, Bodleian library MS Digby 86; London, British Library MS Arundel 248; London, British Library MS Egerton 613; London, British Library MS Egerton 2253; London, British Library MS Harley 978; Kent, Maidstone Museum A. 13; Cambridge, St. John’s College MS E.8; London, British Library MS Royal 12 E.i; Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson G18.

With the exception of the criticism of Harley 978, the manuscript containing the famous “summer canon,” which only contains one piece of Middle English poetry, the scholarly discussion of the miscellanies’ lyrics rarely touches on music (with the notable exception of Helen Deeming’s assiduous work). This critical silence is particularly disconcerting because several of these manuscripts either have notes or signs of music in them, or their lyrical texts have music attached to them in other manuscripts. What I would like to propose, then, is a narrow sampling that will give us a wider picture of what the lyrical record may reveal.

Poetic and Musical Samplings of the Lyric Page

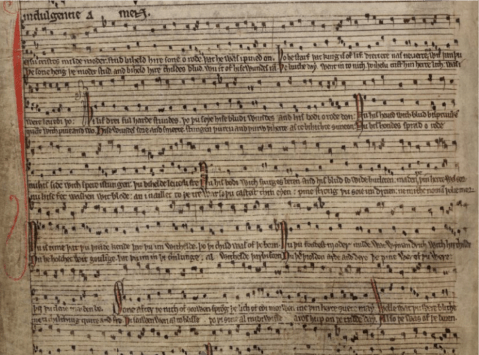

The manuscript layouts of a sample of these medieval multilingual musical miscellanies reveal how musical notes and letters were, at times, considered in the same category. The mise-en-système of these manuscripts also reveal the fluidity, creativity, and cues for audience/listener/reader’s (including the scribal compiler) ability to mashup the multilingual musical matrix. In the manuscript Arundel 248, music is attached to the lyrics, but it is laid out in quite an unusual way. Arundel 248 contains mostly Latin religious texts, including several tracts on sin. However, near the end, there are several lyrical texts that also appear in Digby 86; Jesus 29; and Rawlinson G. 18. On f. 154r, the entire page has Latin, Anglo-Norman, and English verse texted to music. What is interesting about this page, especially in comparison to other musical pages in the MS and the standard layout of thirteenth-century English music, is the folio’s mise-en-page. The scribe has literally laid out a series of lines (particularly in the top half) that then places English poetry, Anglo-Norman French poetry, and Latin poetry with English musical notation. The lack of specific stave lines (though they appear in other parts of this manuscript and at the bottom of this folio) means that the technology of this particular form of sound recording has allowed all these different things—English musical notes, English vernacular notation, Latin notation, and Anglo-Norman vernacular notation—equal space and play. They all have been squeezed onto these black ruled lines (at the top). The mise-en-page, then, allows linguistic differences to be on par with differences in sonic styles. What this manuscript ultimately creates is a miscellany of sound.

The page’s layout cues a sonic palimpsest—or, in contemporary terms, a sonic mash-up—and suggests potentially simultaneous performance. In fact, this vocal performance becomes even more complex in the next slide, f. 154v, because the texted English lyric is a polyphonic piece that also, in many of its manuscripts, has Latin lyrics. This is “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder,” (DIMEV 2831 http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=2831) which comes with English lyrics and texted music. It appears to be a version of “Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem,” though the standard version with music appears in St. John’s College, MS E.8 with the standard English lyrics underneath the melody (DIMEV 5030 http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=5030 ). The latter English lyric connected to “Stabat Iuxta” is “Stand wel moder” and there are several versions of the lyric without music—Digby 86, Harley 2253, Royal 8 F.ii, Trinity College, MS Dublin 301. Another manuscript, Royal MS 12 E.i, contains the same music for “Stand wel moder.” Deeming has noted that the lyrics of this version, “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” correspond closely to “Stabat Iuxta” and could be sung with the standard melody (as seen in Royal 8 F.ii) as a contrafactum. However, you can do a mashup of “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” and its accompanying music juxtaposed with the text and music of “Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem.” As an experiment, I had Camerata, the early Music Group at Vassar College, record this piece, “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” from Arundel 248 with the musical version of “Stabat Iuxta” from St. John’s College MS E.8 (Found in Deeming’s Songs in British Sources (196, 201, 210-211). Other than direction on how to pronounce Middle English (as well as the accompanying contemporary editions of each lyric), I left the performance details to the group themselves to figure out. This is what they recorded – this is the medieval mashup.

The performance shows the creative possibilities of the page, and how music is a very distinct kind of sound player. What song—and particularly multi-part song—has done, is to generate sonic harmony out of linguistic babel. There is a pattern of circulation that intertwines music (both monophony and polyphony) with multilingual lyrics, and this manuscript especially demonstrates those sonic possibilities. These pages demonstrate a diverse soundscape that records and imagines an interesting multimedia and multilingual voice at play. In essence, Arundel 248 displays the different possibilities a reader could have in switching between or layering different modes of sound.

“Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem.” London, British Library MS Arundel 248, f. 154v.

—

Featured image “staff” by Arko Sen @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND

—

Dorothy Kim is an Assistant Professor of English at Vassar College. She is a medievalist, digital humanist, and feminist. She has been a Fulbright Fellow, a Ford Foundation Fellow, a Frankel Fellow at the University of Michigan. She has been awarded grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Mellon Foundation. She is a Korean American who grew up in Los Angeles in and around Koreatown.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Blue Notes of Sampling–Primus Luta

Remixing Girl Talk: The Poetics and Aesthetics of Mashups–Aram Sinnreich

A Tribe Called Red Remixes Sonic Stereotypes–Christina Giacona

Mouthing the Passion: Richard Rolle’s Soundscapes

Each of the essays in this month’s “Medieval Sound” forum focuses on sound as it, according to Steve Goodman’s essay “The Ontology of Vibrational Force,” in The Sound Studies Reader, “comes to the rescue of thought rather than the inverse, forcing it to vibrate, loosening up its organized or petrified body (70). These investigations into medieval sound lend themselves to a variety of presentation methods loosening up the “petrified body” of academic presentation. Each essay challenges concepts of how to hear the Middle Ages and how the sounds of the Middle Ages continue to echo in our own soundscapes.

The posts in this series begins an ongoing conversation about medieval sound in Sounding Out!. Our opening gambit in April 2016, “Multimodality and Lyric Sound,” reframes how we consider the lyric from England to Spain, from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries, pushing ideas of openness, flexibility, and productive creativity. We will post several follow-ups throughout the rest of 2016 focusing on “Remediating Medieval Sound.” And, HEAR YE!, in April 2017, look for a second series on Aural Ecologies of noise! –Guest Editors Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

—

A soundscape is an aural-based landscape, an auditory environment that surrounds a listener and constructs space. In 2009 the composer, John Luther Adams, created a music installation in Alaska that experiments with the boundaries of soundscape. Utilizing geological, meteorological, and magnetic data, Adams tuned and transformed the sounds of the landscape into electronic sound.

In his “Forward” to John Luther Adams’s composer journals compiled as The Place Where You Go to Listen, New Yorker music critic, Alex Ross comments that Adams’s work with composing with the atmospheric, geological, and ecological sounds of Alaska reveals a forbiddingly complex creation that contains a probably irresolvable philosophical contradiction. On the one hand, it lacks a will of its own; it is at the mercy of its data streams, the humors of the earth. On the other hand, it is a deeply personal work, whose material reflects Adams’s long-standing preoccupation with multiple systems of tuning, his fascination with slow-motion formal-processes, his love of foggy masses of sound in which many events unfold at independent tempos (x).

Thinking with Adam’s project and considering how sound surrounds us and can be tuned and transformed, as well as brought to the forefront of our sense perception, I turn to the medieval hermit, Richard Rolle, and his work with canor in his lyrics. In what follows, I consider the enmeshed ecology divine lyrics may invoke, and how the body—as an instrument—may experiment with, mimic, and contemplate divine sounds.

If hills could sing. Photo of Juneau Alaska by Ian D. Keating @Flickr CC BY.

In Rolle’s work, the experience of song, or canor, is one of the highest mystical gifts. As with John Luther Adams, sound unfolds in ways both translatable and ineffable. Canor creates a kind of being, one that creates place and, then, surpasses it. As he writes in the Incendium Amoris at the moment of his receiving the gifts of God:

I heard, above my head it seemed, the joyful ring of psalmody, or perhaps I should say, the singing […] I became aware of a symphony of song, and in myself I sense a corresponding harmony at one wholly delectable and heavenly (93).

In this initial receipt of canor, Rolle is made aware of aural space and the way that it is mimicked in his own biology. The space of the sacred church is transformed into an eternal space that resonates harmonically with God. In this, his first mystical experience, the musical song he hears above him transforms him internally: “my thinking turned into melodious song and my meditations became a poem, and my very prayers and psalms took up the same sound” (93). This transformation erases the boundaries between hearing external song and the translation of the internal song, and tunes Rolle into the ecology of sound, as Adams phrases it in The Place Where You Go to Listen, a “totality of the sound, the larger wholeness of the music” (1). Rolle’s body becomes a musical instrument beyond its initial sound capabilities and it resonates with the chapel space itself to become a larger harmonious work. Harmony in the form of these mystically experienced, enmeshed vibrations suggests both a local and cosmic allusion to complex systems of divine transcendence and immanence.

Detail of an angel with a musical instrument at All Saints’ Church on North Street in York. Image by Lawrence OP @Flickr CC BY-NC-SA.

By invoking the sounds of the Passion, conflating time and sound, and experimenting with the mouth of the lyricist to perform divine sounds, Rolle attempts to capture the panoply of emotion, action, and object surrounding his mystical experience and devotion by singing it. Invoking a queer temporality, Rolle weaves past and present, sound and sight, Jesus and singer, into an immersive, divine soundscape. The song reveals that there is no outside in the connection between the body as instrument and the God-sound.

The making of the divine into song for Rolle is a praxis, an active way to reconsider the relationship between God and man beyond visualization. Rolle’s use of the lyric is an ecological thought, what Tomothy Morton dubs a “reading practice” in The Ecological Thought that

makes you aware of the shape and size of the space around you (some forms, such as yodeling, do this deliberately). The poem organizes space […]. We will soon be accustomed to wondering what any text says about the environment even if no animals or trees or mountains appear in it (11).

In contemplating a lasting Love in , Rolle considers the gap between love and life, or, more specifically a love that is a lasting life and a love that quickly fades. This becoming-love must be separated out from other kinds of love that separate the singer from the community. Can love manifest itself in sound? Rolle exemplifies love’s abundance in the fire that “sloken may na thing” in “A Song of the Love of Jesus” (6). Love is represented as an excessive fire, one that nothing can put out and, therefore, everything is subsumed in it.

Stained glass depicting burning forests from a Richard Rolle poem at All Saints’ Church on North Street in York. Image by dvdbramhall CC BY-NC-SA.

But it is the sound of fire that Rolle connects with Love’s embrace. Rolle suggests an ecological moment, not in an apocalyptic way, but as a fire that creeps into all crevices. Nothing can “sloken” it—the sibilance of the consonant blend ‘sl’ gestures toward crepitation. It is the sound of fire touching the object as it prepares to consume—to take it into itself—as well as reveal Love’s movement in space. Rolle considers that love is created through the sound of fire (which, in his other works is an emotion he struggles with and not a visual fire).

In the lyric “Song of Love-longing to Jesus,” Rolle addresses the relationship between love and Jesus but rather than meditate on the nature of that love, as in the previous lyric, Rolle meditates on the event that causes that love: the Crucifixion. The lyric is bookended by violent acts. At the beginning, Rolle asks Christ to “take my heart intil þy hand, sett me in stabylte” (4) and “thyrl my sawule with þi spere, þat mykel luf in men has wroght” (6). In both these cases Christ’s hand and spear enter into Rolle in order to affect change. In the first line, it is to settle his heart—a theme that Rolle repeats in many of his writings. The stability of the heart allows it to open so that Christ can take up residence and, in that “indwelling,” the soul and Christ become one.

In the second piercing, the spear pierces the soul and Rolle seems to be implying that this piercing has already been done; the second piercing itself is the action that has opened the human to love. As Jesus was pierced by the lance of the Roman soldier, the soul is pierced by Jesus and in that act, love is made or “wroght.” In the second piercing, the ‘thyrl” becomes an important word because of its relationship between sonic resonance and mouth articulation. The spear pierces the soul and Rolle plays with the mouthing of the word as a kind of reverse piercing. The interdental fricative configuration of the voiced “th” in the word “thyrl” made by scraping the tongue between the teeth to form the word is like the removal of the spear from the wound itself. The lips make a wound shape and the tonguing of wounds reveals the intimacy inimical to the movement of the mouth, to sound out this pain and curl the lips to connect the lyricist with Christ.

The latter event of the poem is the scene of the Crucifixion itself. As Jesus has first pierced Rolle and in that event awoken or caused Love, we can imagine the spear as a brief linking object, something that erases the boundaries between Christ and Rolle. However, the middle third of the poem relates how Rolle lives a life of longing—and the love of Jesus will resolve this longing: “I sytt and syng of lufe-langyng, þat in my hert is bred” (29). The song is a result of the piercing; it is as if the removal of the spear has opened up a new song: that of love-longing. Rolle is lamenting the loss of the spear. The love-longing song, then, fills the hole left by the spear.

Image by .sanden. @Flickr CC BY-NC-SA.

The lyric further explores the soundscape of the Crucifixion. The meditation on the Crucifixion begins with Christ bursting forth. If the first image of the lyric is of Rolle being pierced inwardly, Christ ends the poem with a flowing out: “His bak was in betyng, and spylt hys blessed blode; þe thorn corond þe kyng, þat nailed was on þe rode” (35-36). Notice the repetition of “b” and the “th” consonant blend. The “b”’s recreate the lashes, the “th”’s repeat the piercings (the crown, the hands, the legs). The Passion is captured in two lines of sounds, but Rolle underscores the piercing of Christ as a way to show his overabundance—the flowing out of Christ in the lyric is another way to remove the boundary between singer and Christ—Christ also becomes the song as He is bound with the flowing rhyming words: fode/stode/blode/rode mimic the promise of the Passion.

Let us look closely at this stanza’s rhyme. The first and third, fode and blode, refer to the Eucharist and wine. It is out of the second and forth words: stode and rode from which we get that Eucharistic event. Jesus is beaten and Crucified; the Eucharistic feast of body and blood (or “aungel fode”) are a reminder of that event. In other words, Rolle has contained the temporal connection between Eucharist and Crucifixion in four rhyming words and the lyric becomes a witness to the sound of this event.

Rolle’s experiments with the mouthing of sound and the queer temporality of sound in his lyrics reveal Rolle’s attempt to capture canor textually. To sing God is an attempt at harmony with the divine.

—

Featured image from a mural in the Dominican friars’ chapel in the Angelicum, Rome. Photo by Lawrence OP @Flickr CC BY-NC-SA.

—

Christopher Roman is Associate Professor of English at Kent State University His first book Domestic Mysticism in Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe deals with the creation of queer families within mystical theology. His forthcoming book Queering Richard Rolle deals with the intersection of queer theory and theology in the work of the hermit, Richard Rolle. His research also deal with quantum theory and Bede, ecocritical theory, and medieval soundscapes. He has published on medieval anchorites, ethics in Games of Thrones, and death and the animal in the works of Geoffrey Chaucer.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Introduction: Medieval Sound–Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

SO! Reads: Isaac Weiner’s Religion Out Loud: Religious Sound, Public Space, and American Pluralism–Jordan Musser

“I Love to Praise His Name”: Shouting as Feminine Disruption, Public Ecstasy, and Audio-Visual Pleasure–Shakira Holt

Recent Comments