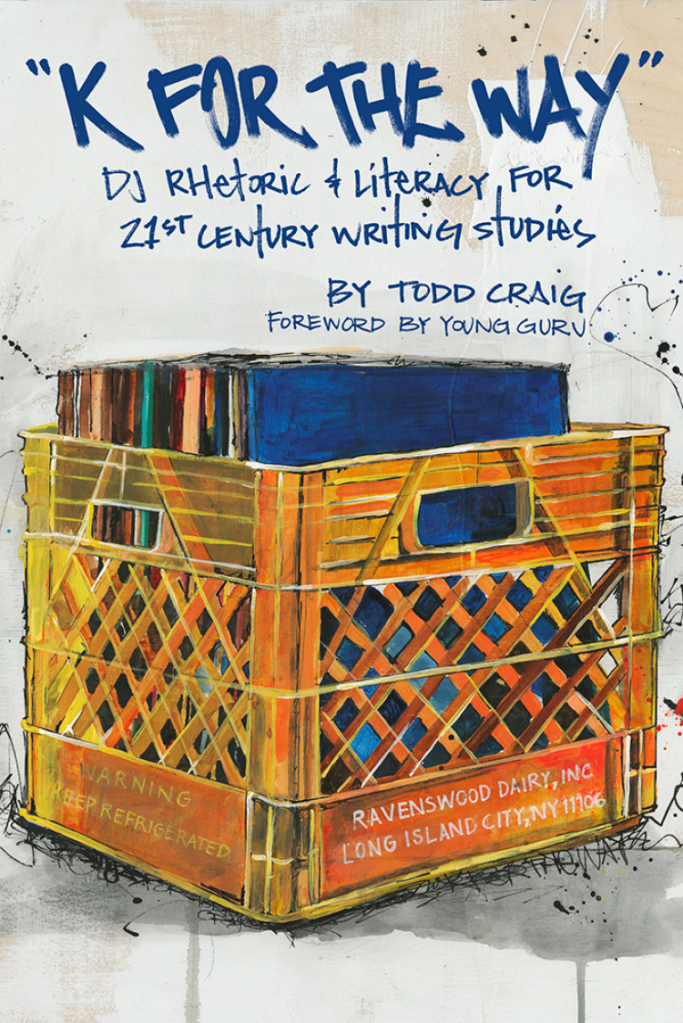

SO! Reads: “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies

or, Last Summer a DJ Saved My Life

“Hip Hop does work that a lot of other things don’t do” Young Guru (viii).

The way that we imagine English Studies, specifically Composition and Rhetoric (Comp/Rhet), today needs a radical shift. Specifically, we need new techniques for Writing Studies pedagogy to reach students in a more meaningful and contemporary fashion. Todd Craig’s “K for the Way:” DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies (Utah State University Press, 2023) both documents the need for this shift and enacts it. Craig’s work enables us to recognize the pedagogical impact on writing that Hip Hop has had over the last 50 years—specifically how the DJ/deejay as twenty-first century new media reader and writer teaches students not just to think about sound, but to compose with it, too.

An Associate Professor of English at CUNY Graduate Center, Craig has little desire to shake the foundations of English Studies, but instead do what Hip Hop has always done—make a way where there is none. The point is to (re)imagine new ways of doing old things; in this case, of teaching and reaching students who arrive in First-Year Writing courses. “K for the Way” does more than demonstrate the ways in which the DJ is a twenty-first century pedagogical savant; it also teaches readers, using DJ Rhetoric and DJ Literacy, about the culture that makes them possible.

This summer, a DJ really did save my life: as someone who feels consistently overwhelmed by the vast nature of scholarly discourse, “K for the Way” gave me a chance to breathe, to identify with something that has been a part of me for the better part of my life, and to see myself in a conversation about a topic I am more than passionate about. For Craig, community, history, and culture are the core of his mission as a scholar, educator, and DJ.

Craig defines several new terms that bridge the worlds of Hip Hop and Composition and Rhetoric. First, we have DJ Rhetoric, which can be understood as the modes, methodologies, and discursive elements of the DJ. For Craig, it “encompasses the quality of oral, written, and sonic language that displays and expresses sociocultural, historical, and musical meanings, attitudes, and sentiments” (23). Next, there is DJ Literacy, which is the “sonic and auditory practices of reading, writing, critically thinking, speaking, and communicating through and with the rhetoric of Hip Hop DJ culture” (23). These two definitions, operating in conjunction, situate the DJ as a kind of griot, a figure that Adam Banks invokes as a carrier of tradition, stories, and histories in Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age (Studies in Writing and Rhetoric) (2011). The mission of the griot is to carry stories and translate them to various audiences while adhering to the rhetorical conventions and modes of whichever audience they find themselves before; similarly, the DJ is responsible for “communicating the pulse and the evolution of a culture that once sat as ‘underground’ but now has dramatically evolved to ‘mainstream’” (25). These definitions serve as guides for the reader as they are tethered to all of the concepts and (re)imagining happening throughout the book.

Craig is intimately close to the work he is doing. He lives and breathes Hip Hop; and what should a book about the Hip Hop DJ be if not written by someone who embodies the role, culture, and practice of DJing? Craig uses a a research methodology known as hiphopography in which Hip Hop ways of being are central to studying it. Coined by James G. Spady, this term is defined as “a shared discourse with equanimity, not the usual hierarchical distancing techniques usually found in published and non-published (visual-TV) interviewers with rappers” (27). Craig states that hiphopography “allowed me to engage a variety of Hip Hop DJs while also maintaining my own shared values and sentiments around my love of Hip Hop culture and DJ practices” (28). Hiphopography constructs a conversational, intimate space—touched by history, culture, and music—wherein the interviewer and interviewee can engage and produce meaningful data. This methodology—and Craig’s many interviews with DJs about their craft—becomes part of the text’s core as we begin to see how Craig’s two-pronged argument connects DJ Rhetoric and DJ Literacy to bring both life throughout the book.

If one understands the DJ as a twenty-first century rhetorician and compositionist and considers the ways in which the DJ is a cultural meaning-maker, sponsor, and master sampler, then one can clearly see the connections between the DJ, DJ culture, and Writing Studies in the contemporary moment. In the first part of his argument supporting the significance of DJ Rhetoric and Literacy in writing pedagogy Craig asserts that, “it is essential that the academy at large works to strengthen students’ undergraduate experiences by reinforcing their racial, ethnic, and cultural ties” (14). This perspective provides the foundation for the second part of his argument that “the DJ (and thus, Hip Hop DJ culture) is the epicenter of Hip Hop culture’s creation” (23). Taken together, these dynamic arguments make the claim that the DJ offers a powerful model of a new media reader, writer, and critic. Today, our students come to writing classrooms with a “vast array of cultural capital. . .in their philosophical and cultural backpacks” (107). If we, as writing teachers, want to honor that cultural capital and build with it, we should follow Craig’s lead and look toward the DJ for some pointers on how to expand students’ access to a language that represents them.

Readers will also see a developing research agenda in “K for the Way” that thinks toward changing the culture beyond the present, while acknowledging the groundwork laid for the current moment and building genealogically upon that foundation, just as DJs do with sampling. Craig best exemplifies this when he writes, “in order to fully engage in a conversation—whether intellectual, pedestrian or otherwise—that discusses what DJ Rhetoric might look like, one has to think about the cultural and textual lineage of sponsors and mentors” (51). This notion of textual lineage is borrowed from Alfred W. Tatum who explains the term as “Similar to lineages in genealogical studies” and continues to note that textual lineage is “made up of texts (both literary and nonliterary) that are instrumental in one’s human development because of the meaning and significance one has garnered from them” (Tatum, qtd. in Craig, 51). Craig builds upon Tatum’s idea by introducing sonic lineage, which follows the same logic as Tatum’s term, but through sound (51). What becomes apparent, is that the DJ, as a cultural sponsor, can deploy sonic lineage as a way of communicating history and culture to members within and outside of the Hip Hop community and, more specifically, DJ culture.

Chapter three, especially, works at the interdisciplinary junction of Sound Studies, Writing Studies, and Hip Hop studies to convey a clear critique of the dominant discourse surrounding plagiarism. Craig is unsatisfied with the black-and-white conception of plagiarism as it presents itself in the academy. As a result, he moves to inquire “how we as practitioners [of teaching composition] approach citation methods and strategies within a twenty-first century landscape” (75). Craig promptly turns us toward the DJ’s conceptualization of sampling as a citation practice. Sampling in Hip Hop, as defined by Andrew Bartlett, “is not collaboration in any familiar sense of the term. It is a high-tech and highly selective archiving, bringing into dialogue by virtue of even the most slight representation” (77). The highly selective archiving, a.k.a crate diggin’, builds upon the idea of sonic lineage.

For the DJ, the process of diggin’ through crates to find that right sound, that one joint that going to get the party jumpin’, is a key element in the practice of “text constructing” (79). The Hip Hop sample functions alongside an understanding, offered by Alasdair Pennycook, of “transgressive-versus-nontransgressive intertextuality,” which, for an academic audience, complicates the idea of plagiarism.. The DJ becomes a figure through which we can understand intertextuality, sampling becomes the practice through which we can see parallels to citation through text construction, and the mix is where we begin, with the help of Pennycook, to complicate notions of plagiarism. In this chapter, readers are able to understand through sound.

Subsequently, Craig explores the concept of revision as it relates to the DJ’s ability to engage with an emcee on the point of “remix as revision” (107). Building from on Nancy Sommers’ article, “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers,” Craig lifts and examines four strategies of revision through the lens of the Hip Hop DJ: deletion, substitution, addition, and reordering (Sommers, qtd. in Craig, 107). These practices not only identify the Hip Hop DJ as a master of revision but also center the DJ, in the context of the writing classroom, as a key figure for understanding editorial practice. As teachers of writing—and especially for those of us who are deeply connected to Hip Hop culture—we have traditional scholars, such as Sommers, but we also have the DJ as cultural scholar, which offer new models with communicating and practicing the craft of writing in the twenty-first century.

Chapter Five, which is co-written by Craig and Carmen Kynard, centers on six women DJs: DJs Spinderella, Pam the Funkstress, Kuttin Kandi, Shorty Wop, Reborn, and Natasha Diggs to work toward developing a “Hip Hop Feminist Deejay Methodology” that positions women in Hip Hop culture as a key source of key knowledge production–as meaning-makers, theoreticians, storytellers–and as tastemakers in twenty-first century discourse about education, technologies, race, and gender. This chapter is also apt representation of hiphopography at work, as both Craig and Kynard ground their position in the interviews of these six women deejays, “deliberately situating their stories first… as opposed to the usual academic expectation that a tedious delineation of methods and an extant literature review come before a discussion of the actual subjects” (123).

In part, this chapter focuses on the affordances and limitations—political, social, and economic—present in DJ culture, and the effects it has on these women DJs to make it do what it does. For example, the introduction of the digital software Serato has simultaneously made access to music easier, and complicated access to the cultural archive that made the music possible in the first place. Natasha Diggs, states, “While she values the ability to access mp3 files so readily, she argues a deejay’s research and craft suffer, because many times the mp3 files do not include information about an artist’s name, history, or band” (129). Pam the Funkstress ties this sentiment up nicely when she argues, “There’s nothing like vinyl” (129).

The final chapter is fashioned like a Hip-Hop outro, with Craig leaving with a few parting ideas. Most important among them is his vision of “Comp 3.0,” a version of Comp/Rhet wherein “we have to push the scope of writing and rhetoric—with or without the field’s permission or acknowledgement” (171). For scholars of composition and rhetoric and writing teachers who ground part of their understanding of the field in Black Studies, Hip Hop, and the DJ, we gotta make it do what it do, regardless of who says what! Comp 3.0 does not seek approval or recognition from the powers that be; instead, it focuses on the new ways of thinking and writing, and of teaching, that we are able to conjure—with history, culture, and practice propelling us—when we invoke that which got us to the academy in the first place.

What is at stake, for those of us who engage Black Studies, Sonic Studies, Comp/Rhet, and Hip Hop Studies as critical points of departure for the teaching of writing, is that our presence—our being, methods, and our teaching—is crucial for developing a genealogy of scholars and world citizens who are aware of the myriad possibilities present in the twenty-first century.

—

Featured Image: Cover Art for “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies by Cathey White

—

DeVaughn (Dev) Harris is a PhD student studying composition and rhetoric in NYC. His academic interests are mainly in writing studies and pedagogy, but those are often supported by other sub-interests in music, creative writing, African American studies, and philosophy. When not reading or writing, Dev enjoys making music wherever and however possible. He has published music before under the collective AbstraktFlowz.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: Classroom Sonic Consciousness in the Playlist Project—Todd Craig

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening--Airek Beauchamp

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom- Carter Mathes

Contra La Pared: Reggaetón and Dissonance in Naarm, Melbourne–Lucreccia Quintanilla

Ill Communication: Hip Hop and Sound Studies–Jennifer Stoever

SO! Amplifies: Regina Bradley’s Outkasted Conversations

A Listening Mind: Sound Learning in a Literature Classroom–Nicole Brittingham Furlonge

Ronca Realness: Voices that Sound the Sucia Body

This series listens to the political, gendered, queer(ed), racial engagements and class entanglements involved in proclaiming out loud: La-TIN-x. ChI-ca-NA. La-TI-ne. ChI-ca-n-@. Xi-can-x. Funded by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation as part of the Crossing Latinidades Humanities Research Initiative, the Latinx Sound Cultures Studies Working Group critically considers the role of sound and listening in our formation as political subjects. Through both a comparative and cross-regional lens, we invite Latinx Sound Scholars to join us as we dialogue about our place within the larger fields of Chicanx/Latinx Studies and Sound Studies. We are delighted to publish our initial musings with Sounding Out!, a forum that has long prioritized sound from a queered, racial, working-class and “always-from-below” epistemological standpoint. —Ed. Dolores Inés Casillas

—

My Puerto Rican grandmother used to sing Pedro Infante’s “Las mañanitas” to all the women in the family on their birthdays, so naturally I grew up thinking this was a Puerto Rican song. Not quite – it’s Mexican. When my family came to New York City from Puerto Rico in the 1950s, they were starved of warm waters, mountains, and family members, but they were not starved of Spanish-language music and media thanks in large part to Mexico’s Golden Age of Cinema. In the Bronx, Puerto Ricans would go the theaters to watch movies like Nosotros los Pobres (1948),which popularized boleros like “Las Mañanitas.” This movie-going ritual in the wake of relocation and diaspora has provided the birthday soundtrack to my life.

My mother grew up listening to her father sing boleros, and she would later sing with the Florida Grand Opera Chorus when I was a child. My early knowledge of opera came from her. Growing up in Miami Beach, I would also listen to reggaetón and hip-hop in afterschool programs. The Parks & Recreation department would host dances for us, and that was where I first learned to dance perreo. My early musical surroundings represent what it means to be a colonial subject, to hear the Italianate vocal legacies of opera mixed with the Afro-Diasporic and Indigenous rhythms of reggaetón. This post contextualizes my experience within bolero’s colonial history and legacy particularly its operatic disciplining of brown and Black bodies and voices. Reggaetóneras provide models for sonic subversion by being ronca, raspy, or breathy, and thus overriding internalized Eurocentric dichotomies of feminine and masculine vocal timbres.

When I began my own operatic training in college, I was constantly told to “purify” my voice, to resist vocal “fry,” and to handle my acid reflux by avoiding spicy foods. I was steered away from singing the pop songs I had grown up with, and kept many musical activities secret, like when I soloed for the tango ensemble and my a cappella group. In graduate school, thanks to my Latina roommates, I began listening to reggaetón again. I reunited with the voices that raised me and was reassured that their teachings of resistance would always present themselves when I needed them.

After 20 years of listening to Ivy, I have located the descriptor that most closely encapsulates the way her voice sounds to me: ronca. This is Spanish for hoarse, and in my experience, it’s been used colloquially, mostly by women, to describe moments when their throats might feel sore, and their voices sound raspy, or masculine, even. Ronca has been articulated as an epistemology of vocal sounding in the artistry of lower-class Black reggaetón creators like Don Omar and more recently, Ozuna. Sounding ronca is a signifier of realness, of truly knowing the struggle of race and class oppression. It is a vocalization of full-body rage fueled by poverty and colonization.

Ivy’s voice is so special to me because she sounds like my aunt when she’s had a long day, my mom when she’s yelling, and my grandma after years of having long days and yelling at people. She sounds like the raw, unfiltered power that comes from exhaustion. She sounds like inner will and justified fury. She sounds like yelling at landlords and ex-husbands for hot water and child support. She sounds like age. And she always has, even when she was “young.” And this sound is even more beautiful and life-giving to me after 4+ years in a classical voice program that told me it was bad to sound hoarse or raspy, surveilled my eating, and perpetuated the colonization of Native and Black peoples through musical subjugation.

Operatic training utilizes mechanisms that are opposite of what is “natural” for me as a poor Latina from the barrio. It asks me to lift my voice, clarify it, and feminize it. This, to me, is antithetical to the girl who laughs really loudly, gets raspy often from yelling and eating too many Takis, and loves to sing from her chest. Ivy’s voice empowers my place as the antithesis. Even as I sang classically in college, my voice was still often described as “soulful,” “hoarse,” “raspy,” “throaty.” My voice, although in a moment of attempted cleanup in college, was read as having previously engaged in genres that disrupt colonial dichotomies of “art” and “noise.” The sonic Blackness– in particular the exoticized and tropicalized Blackness of Latinidad in the U.S.- of my timbre was legible, and perhaps even hyper-audible, in moments when I was trying to adapt to European art forms. Raquel Z. Rivera asserts in New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone (2003) that Latinidad doesn’t take away from Blackness but adds an element of exoticism to the Blackness. Thus, I have come to understand ronca voices as representative of a Latina/e liberatory sonic and embodied praxis that resists the derogatory discourse around racialized voices predicated on European ideals of cleanliness.

The ronca voice is negotiating suciedad, Deborah Vargas’ analytic for how queers of color may reclaim their abject bodies and social spaces. Readings of my voice in predominantly white spaces were contextualized by my queer ambiguously-brown body, which in direct opposition to whitening regimes, was sounding suciedad. This is what ronca voices do, and what I conceptualize as “ronca realness”: the tendency of Latinas/es to not hide behind the voice but rather keep it real with the audience via their vocal timbre. Ronca voices sound another option to Barthes’ hegemonic article “The Grain of the Voice,” which has been applied to Ivy Queen and Don Omar in Jennifer Domino Rudolph’s “‘Roncamos Porque Podemos,’” and Dara Goldman’s “Walk like a Woman, Talk like a Man: Ivy Queen’s Troubling of Gender.” I intend ronca realness to be understood as a queer of color vocal analytic born from community and lived experience.

Ronca voices reflect emotional states, flip colonial gendered vocal scripts, reveal if the singer had coffee that morning and Hot Cheetos the night before, and navigate tough musical contours with strain and stress; most importantly, they refuse to be white(ned). In college, my ronca realness was not always a choice. Keeping it real, in general, is sometimes undecided upon prior to the act of realness; it is an additional and deeply engrained responsibility that queer people of color have in white spaces to sound their dissent, or else face the continued exploitation of their communities. Further, these acts of realness may not even be legible as such but are often coded as bad behavior or an attitude problem.

Within communities of color and (im)migrant communities, it’s important to recognize that Ivy Queen’s ronca timbre was permissible because she was light-skinned, thin, and usually took on the masculine role of the rapper, rather than the feminine role of the dancer, in several of her videos. These privileges have left Afro-Latina ronca reggaetóneras like La Sista in the shadows.

La Sista has veered away from sounding ronca in recent years, but in her debut album, Majestad Negroide (2006), she praised Yoruba goddess Yemaya and Taino cacique Anacaona with a hoarse, raspy, bold sound. She is the Afro-Indigenous Latina many of us needed growing up, and her absence speaks to the ways in which Black ronca voices are policed and erased within Latinx culture and elsewhere. Let us praise her now.

—

Featured Image: Still image by SO! from RaiNao’s “Tentretiene”

—

Cloe Gentile Reyes (she/her) is a queer Boricua scholar, poet, and performer from Miami Beach. She is a soon-to-be Faculty Fellow in NYU’s Department of Music and earned her PhD in Musicology from UC Santa Barbara. Her writing explores how Caribbean femmes navigate intergenerational trauma and healing through decolonial sound, fashion, and dance. Cloe’s poems have been featured in the womanist magazine, Brown Sugar Lit, and she has presented and performed at PopCon, Society for American Music, International Association for the Study of Popular Music-US Branch, among several others.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Contra La Pared: Reggaetón and Dissonance in Naarm, Melbourne—Lucreccia Quintanilla

“How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?”: DJ Irene, Sonic Interpellations of Dissent and Queer Latinidad in ’90s Los Angeles—Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr.

Unapologetic Paisa Chingona-ness: Listening to Fans’ Sonic Identities–Yessica Garcia Hernandez

SO! Podcast #74: Bonus Track for Spanish Rap & Sound Studies Forum

Cardi B: Bringing the Cold and Sexy to Hip Hop—Ashley Luthers

Recent Comments