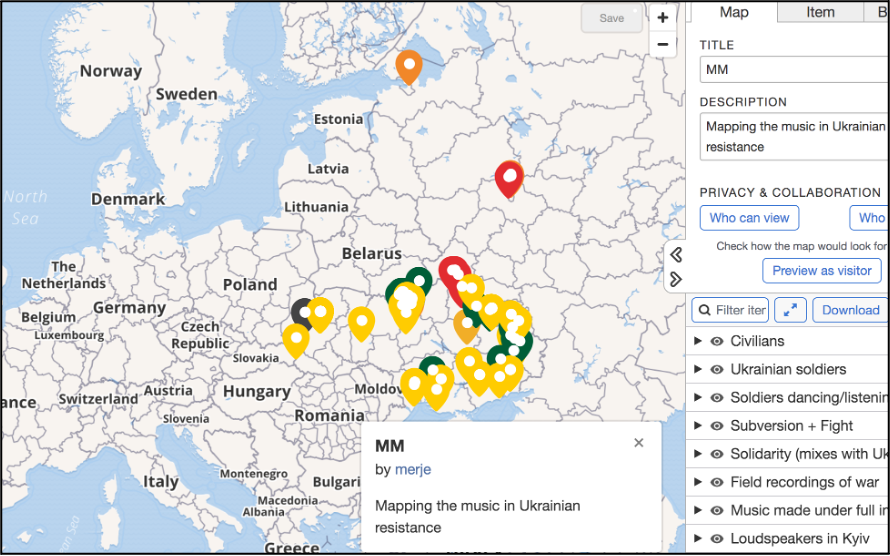

SO! Amplifies: An Interactive Map of Music as Ukrainian Resistance to the 2022 Russian Invasion

https://maphub.net/merje/mm

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

—

BONUS POST: Directly following Merje’s introduction to her music mapping project, SO! has also published is her analysis of the observational research she conducted during the first 55 days of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, drawing from the collection of videographic material from online sources she embedded on this public interactive map. To go directly to that post, click here.

As an Estonian national, I have a regional interest in the relationship between music and cultural identity in Eastern Europe. Popular music has been foundational in building and sustaining Estonian national identity, through the Song Festival tradition which started in 1869, and the Singing Revolution at the end of the 1980s. In the Baltic states, Poland and Ukraine, there are similarities in how music has facilitated resistance to an oppressive regime or invasion.

While other cultural forms can articulate and show off shared values, only music can offer the immediate experience of collective identity (Frith 2007, 264). Looking into the sensitive representation of music in conflict, therefore, is about exercising hapticity with the precarity and suffering in the videos, and ultimately a work of not only academic, but affective labour.

The map format helps visualise the video evidence as it continues to appear in different parts of Ukraine. For accurate analysis, understanding the context, region, and the phase of war in which a musical event originates, is vital. In different parts of the country on the same date, one city can embody a collective feeling of resistance, while the other grief. The map is useful in analysing regional differences in the types of songs performed, and in ‘placing’ the international cases of solidarity. I decided to map the solidarity mixes that directly engage with the musical footage from Ukraine, and to exclude the high number of global fundraising concerts. All map entries depict in some way the role of music in Ukrainian resistance.

The map function is made redundant in posts where the location should not be disclosed for safety reasons, such as this video of soldier Yuriy Gorodetsky performing ‘How Can’t I Love You, My Kyiv’ in a military camp. Additionally, I decided not to embed posts that could inform the Russian military of civilian and humanitarian targets, for example a video from Lviv showing the Philharmonic concert space being used for humanitarian storage.

The focus has been on mapping songs and music, rather than the wider soundscape of war, although sounds such as air raid sirens do appear in some videos. The map includes sections on recorded music, such as this wartime ska track by Mandry, field recordings, and ways in which music has been used in online warfare. Most map entries fall under the civilian resistance category, exploring the following questions:

- What kind of music appears in this resistance? In terms of genre, is it folk, rock, hip hop, or national patriotic song? Is it Ukrainian or ‘Western’? How do the different examples embody national feeling and safeguarding of a culture?

- What is the power of these musical moments, for the artists, for Ukrainians, and for the world? What can music achieve in a conflict environment, and how does it evoke moments of solidarity?

- How does the music reflect the different phases and emotions of the war, from mobilisation, resistance, support, contemplation, to grief?

Similar research questions have been posed by Arve Hansen et al. in A War of Songs (2019) about the 2013-14 Euromaidan protests, in which music carried much of the revolutionary feeling. Adriana Helbig wrote about the Orange Revolution of 2004-05 in Hip Hop Ukraine: Music, Race, and African Migration when the Internet played a huge role in circulating political messages through music, especially as Ukraine’s media was controlled by president Yanukovich (2014). Maria Sonevytsky’s Wild Music (2019) looks at both revolutions and the vernacular Ukrainian discourses of ‘wildness’ as they manifested in popular music during this politically volatile decade.

When looking at Ukraine, we are studying a repeatedly colonised region, where, as part of the former Russian Empire, serfdom was abolished in 1861. Ethnographic research and promotion of a national culture in the decades that followed led to a brief window of independence for Ukraine in 1917, only to be occupied and incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the same year. Unlike Poland and the Baltic states, Ukraine was not independent between the two world wars, which adds depth to Soviet propaganda that permeated the region throughout the 20th century – important context to consider when analysing its struggle for autonomy.

Drawing from Parkes, the relationships of domination and subordination are particularly marked and articulated through music in colonised groups (Parkes 1994). Often, Ukraine is portrayed as a country of two opposing regions: the pro-European West and the pro-Russian East. While there have been two sides opposed to each other since the 2014 Crimean occupation, the linguistic, ethnic, historical and religious divisions in Ukraine cannot neatly fit into this East-West dichotomy. In addition to complicated ethnic boundaries that define and maintain the region’s cultural identities, Ukraine is dealing with a post-colonial struggle to protect its independence from imperialist Russia.

The ‘places’ constructed through Ukrainian music embody these complex issues, notions of difference and social boundaries – the very reason why music is socially meaningful: it provides means by which people recognise identities, places and the boundaries which separate them (Stokes 1994). In a war situation, beyond political and social alliances, we are also looking at music as survival (Stokes 2020).

—

Merje Laiapea is a curator, artistic programmer and writer working across sound, music and film. She is completing her Master’s in Global Creative and Cultural Industries in the Music Department at SOAS, University of London. Within the broad realm of music and cultural identity, her research interests include the expressive power of the sound-image relationship, forms of frequency, and multimodal approaches to research itself. She assists with event production and community engagement at SOAS Concert Series and works as Submissions Advisor for the 2022 Film Africa festival. Merje also broadcasts the occasional radio show and DJ mix. To find out more about Merje’s motivation behind the project, click here to read an interview by the University of London.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig this:

Mapping the Music in Ukraine’s Resistance to the 2022 Russian Invasion–Merje Laiapea

SO! Amplifies: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)—Freddie Cruz Nowell

SO! Amplifies: Marginalized Sound—Radio for All–J. Diaz

SO! Amplifies: Die Jim Crow Record Label

SO! Amplifies: Cities and Memory–Stuart Fowkes

Trackbacks / Pingbacks