Playin’ Native and Other Iterations of Sonic Brownface in Hollywood Representations of Dolores Del Río

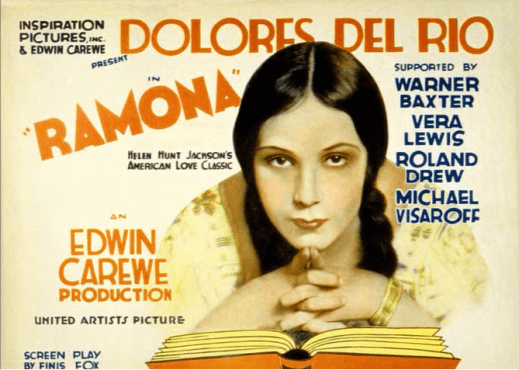

Mexican actress Dolores Del Río is admired for her ability to break ground; her dance skills allowed her to portray roles not offered to many women of color early in the 20th Century. One of her most popular roles was in the movie Ramona (1928), directed by Edwin Carewe. Her presence in the movie made me think about sonic representations of mestizaje and indigeneity through the characters portrayed by Del Río. According to Priscilla Ovalle, in Dance and the Hollywood Latina: Race, Sex and Stardom (2010), Dolores del Río was representative of Mexican nationhood while she was a rising star in Hollywood. Did her portrayals reinforce ways of hearing and viewing mestizos and First Nation people in the American imaginary? Is it sacrilegious to examine the Mexican starlet through sonic brownface? I explore these questions through two films, Ramona and Bird of Paradise (1932, directed by King Vidor), where Dolores del Río plays a mestiza and a Polynesian princess, respectively, to understand the deeper impact she had in Hollywood through expressions of sonic brownface.

Before I delve into analysis of these films and the importance of Ramona the novel and film adaptions, I wish to revisit the concept of sonic brownface I introduced here in SO! in 2013. Back then, I argued that the movie Nacho Libre and Jack Black’s characterization of “Nacho” is sonic brownface: an aural performativity of Mexicanness as imagined by non-Mexicans. Jennifer Stoever, in The Sonic Color Line (2017), postulates that how we listen to particular body(ies) are influenced by how we see them. The notion of sonic brownface facilitates a deeper examination of how ethnic and racialized bodies are not just seen but heard.

Through my class lectures this past year, I realized there is more happening in the case of Dolores del Río, in that sonic brownface can also be heard in the impersonation of ethnic roles she portrayed. In the case of Dolores del Río, though Mexicana, her whiteness helps Hollywood directors to continue portraying mestizos and native people in ways that they already hear them while asserting that her portrayal helps lend authenticity due to her nationality. In the two films I discuss here, Dolores del Río helps facilitate these sonic imaginings by non-Mexicans, in this case the directors and agent who encouraged her to take on such roles. Although a case can be made that she had no choice, I imagine that she was quite astute and savvy to promote her Spanish heritage, which she credits for her alabaster skin. This also opens up other discussions about colorism prevalent within Latin America.

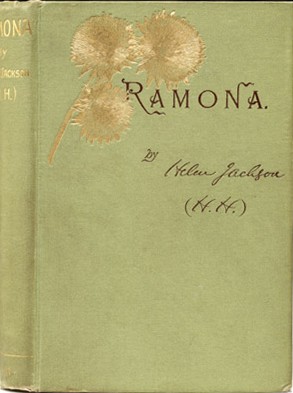

First, let us focus on the appeal of Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona (1884), as it is here that the cohabitation of Scots, Spanish, Mestizos, and Native people are first introduced to the American public in the late 19th century. According to Evelyn I. Banning, in 1973’s Helen Hunt Jackson, the author wanted to write a novel that brought attention to the plight of Native Americans. The novel highlights the new frontier of California shortly after the Mexican American War. Though the novel was critically acclaimed, many folks were more intrigued with “… the charm of the southern California setting and the romance between a half-breed girl raised by an aristocratic Spanish family and an Indian forced off his tribal lands by white encroachers.” A year after Ramona was published, Jackson died and a variety of Ramona inspired projects that further romanticized Southern California history and its “Spanish” past surged. For example, currently in Hemet, California there is the longest running outdoor “Ramona” play performed since 1923. Hollywood was not far behind as it produced two silent-era films, starring Mary Pickford and Dolores del Río.

First, let us focus on the appeal of Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona (1884), as it is here that the cohabitation of Scots, Spanish, Mestizos, and Native people are first introduced to the American public in the late 19th century. According to Evelyn I. Banning, in 1973’s Helen Hunt Jackson, the author wanted to write a novel that brought attention to the plight of Native Americans. The novel highlights the new frontier of California shortly after the Mexican American War. Though the novel was critically acclaimed, many folks were more intrigued with “… the charm of the southern California setting and the romance between a half-breed girl raised by an aristocratic Spanish family and an Indian forced off his tribal lands by white encroachers.” A year after Ramona was published, Jackson died and a variety of Ramona inspired projects that further romanticized Southern California history and its “Spanish” past surged. For example, currently in Hemet, California there is the longest running outdoor “Ramona” play performed since 1923. Hollywood was not far behind as it produced two silent-era films, starring Mary Pickford and Dolores del Río.

The charm of the novel Ramona is that it reinforces a familiar narrative of conquest with the possibility of all people co-existing together. As Philip Deloria reminds us in Playing Indian (1999), “The nineteenth-century quest for a self-identifying national literature … [spoke] the simultaneous languages of cultural fusion and violent appropriation” (5). The nation’s westward expansion and Jackson’s own life reflected the mobility and encounters settlers experienced in these territories. Though Helen Hunt Jackson had intended to bring more attention to the mistreatment of native people in the West, particularly the abuse of indigenous people by the California Missions, the fascination of the Spanish speaking people also predominated the American imaginary. To this day we still see in Southern California the preference of celebrating the regions Spanish past and subduing the native presence of the Chumash and Tongva. Underlying Jackson’s novel and other works like Maria Amparo Ruiz De Burton The Squatter and the Don (1885) is their critique of the U.S. and their involvement with the Mexican American War. An outcome of that war is that people of Mexican descent were classified as white due to the signing of Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and were treated as a class apart. (See Michael Olivas’ anthology, Colored Men and Hombres Aqui from 2006 and Ignacio M. García, White but not Equal from 2008). These novels and films reflect the larger dominant narrative of whiteness and its relationship to nation building. Through Pickford’s and del Río’s portrayals of Ramona they reinforce the whiteness of mestizaje.

Screenshot from RAMONA (1910). Here, Ramona (played by Mary Pickford) finds out that she has “Indian blood.”

In 1910, Mary Pickford starred in D.W. Griffith’s short film adaptation of Ramona as the titular orphan of Spanish heritage. Henry B. Walthall played Alessandro, the Native American, in brownface to mimic physical attributes of the native Chumash of Southern California. Griffith also wanted to add authenticity by filming in Camulas, Ventura County, the land of the Chumash and where Jackson based her novel. The short is a sixteen-minute film that takes viewers through the encounter between Alessandro and Ramona and their forbidden love, as she was to be wedded to Felipe, a Californio. There is a moment in the movie when Ramona is told she has “Indian blood”. Exalted, Mary Pickford says “I’m so happy” (6:44-6:58). Their short union celebrates love of self and indigeneity that reiterates Jackson’s compassionate plea of the plight of native people. In the end, Alessandro dies fighting for his homeland, and Ramona ends up with Felipe. Alessandro, Ramona, and Felipe represent the archetypes in the Westward expansion. None had truly the power but if mestizaje is to survive best it serve whiteness.

Edwin Carewe’s rendition of Ramona in 1928 was United Artists’ first film release with synchronized sound and score. Similar to the Jazz Singer in 1927, are pivotal in our understanding of sonic brownface. Through the use of synchronized scored music, Hollywood’s foray into sound allowed itself creative license to people of color and sonically match it to their imaginary of whiteness. As I mentioned in my 2013 post, the era of silent cinema allowed Mexicans in particular, to be “desirable and allowed audiences to fantasize about the man or woman on the screen because they could not hear them speak.” Ramona was also the first feature film for a 23-year-old Dolores del Río, whose beauty captivated audiences. There was much as stake for her and Carewe. Curiously, both are mestizos, and yet the Press Releases do not make mention of this, inadvertently reinforcing the whiteness of mestizaje: Del Río was lauded for her Spanish heritage (not for being Mexican), and Carewe’s Chickasaw ancestry was not highlighted. Nevertheless, the film was critically acclaimed with favorable reviews such as Mordaunt Hall’s piece in the New York Times published May 15, 1928. He writes, “This current offering is an extraordinarily beautiful production, intelligently directed and, with the exception of a few instances, splendidly acted.” The film had been lost and was found in Prague in 2005. The Library of Congress has restored it and is now celebrated as a historic film, which is celebrating its 90th anniversary on May 20th.

In Ramona, Dolores del Río shows her versatility as an actor, which garners her critical acclaim as the first Mexicana to play a starring role in Hollywood. Though Ramona is not considered a talkie, the synchronized sound comes through in the music. Carewe commissioned a song written by L. Wolfe Gillbert with music by Mabel Wayne, that was also produced as an album. The song itself was recorded as an instrumental ballad by two other musicians, topping the charts in 1928.

In the movie, Ramona sings to Allessandro. As you will read in the lyrics, it is odd that it is not her co-star Warner Baxter who sings, as the song calls out to Ramona. Del Río sounds angelic as the music creates high falsettos. The lyrics emphasize English vernacular with the use of “o’er” and “yonder” in the opening verse. There are moments in the song where it is audible that Del Río is not yet fluent speaking, let alone singing in English. This is due to the high notes, particularly in the third verse, which is repeated again after the instrumental interlude.

I dread the dawn

When I awake to find you gone

Ramona, I need you, my own

Each time she sings “Ramona” and other areas of the song where there is an “r”, she adds emphasis with a rolling “r,” as would be the case when speaking Spanish. Through the song it reinforces aspects of sonic brownface with the inaudible English words, and emphasis on the rolling “rrrr.” In some ways, the song attempts to highlight the mestiza aspects of the character. The new language of English spoken now in the region that was once a Spanish territory lends authenticity through Dolores del Río’s portrayal. Though Ramona is to be Scottish and Native, she was raised by a Spanish family named Moreno, which translates to brown or darker skin. Yes, you see the irony too.

United Artists Studio Film Still, under Fair Use

Following Del Río’s career, she plays characters from different parts of the world, usually native or Latin American. As Dolores del Río gained more popularity in Hollywood she co-starred in several movies such as Bird of Paradise (1932), directed by King Vidor, in which she plays a Polynesian Princess. Bird of Paradise focuses on the love affair between the sailor, played by Joel McCrea, and herself. The movie was controversial as it was the first time we see a kiss between a white male protagonist with a non-Anglo female, and some more skin, which caught the eye of The Motion Picture Code commission. Though I believe the writers attempted to write in Samoan, or some other language of the Polynesian islands, I find that her speech may be another articulation of sonic brownface. Beginning with the “talkies,” Hollywood continued to reiterate stereotypical representations though inaccurate music or spoken languages.

In the first encounter between the protagonists, Johnny and Luana, she greets him as if inviting him to dance. He understands her. He is so taken by her beauty that he “rescues” her to live a life together on a remote island. Though they do not speak the same language at first it does not matter because their love is enough. This begins with the first kiss. When she points to her lips emphasizing kisses, which he gives her more of. The movie follows their journey to create a life together but cannot be fully realized as she knows the sacrifice she must pay to Pele.

I do not negate the ground breaking work that Dolores del Río accomplished while in Hollywood. It led her to be an even greater star when she returned to Mexico. However, even her star role as Maria Candelaria bares some examination through sonic brownface. It is vital to examine how the media reinforces the imaginary of native people as not well spoken or inarticulate, and call out the whiteness of mestizaje as it inadvertently eliminates the presence of indigeneity and leaves us listening to sonic brownface.

—

reina alejandra prado saldivar is an art historian, curator, and adjunct lecturer in the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program and Liberal Studies Department at CSULA and in the Critical Studies Program at CALArts. As a cultural activist, she focused her earlier research on Chicano cultural production and the visual arts. Prado is also a poet and performance artist known for her interactive durational work Take a Piece of my Heart as the character Santa Perversa (www.santaperversa.com) and is currently working on her first solo performance entitled Whipped!

—

Featured image: Screenshot from “Ramona (1928) – Brunswick Hour Orchestra”

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Afecto Caribeño / Caribbean Affect in Desi Arnaz’s “Babalú Aye” – reina alejandra prado saldivar

SO! Amplifies: Shizu Saldamando’s OUROBOROS–Jennifer Stoever

SO! Reads: Dolores Inés Casillas’s ¡Sounds of Belonging! – Monica de la Torre

Speaking “Mexican” and the use of “Mock Spanish” in Children’s Books (or Do Not Read Skippyjon Jones)

Cinco de Mayo. ‘Tis the season when many Americans don sombreros, order their frozen margaritas, and, God help us, speak “Spanish.” We are well used to hyper Anglicized renditions of “amigo,” “adios,” and happy hour specials brought on by the commercialization of Cinco de Mayo. The holiday celebrates a significant event in Mexico’s history – the battle of Puebla and victory over France in 1862 – through narrowing ideas about language, culture, and tequila. That said, let’s not just blame Cinco de Mayo for the disconcerting use of Spanish. Unfortunately, the incessant use of phrases such as “ay caramba” and “no problemo” are heard much, much earlier in contemporary children’s books.

The New York Times recently published the startling figure that just 93 of the 3,200 children’s books published in 2013 were about African American children. Within these few 93 texts, African American children all-too-often read about themselves within the past tense, in reference to slavery and civil rights legacies. Children of color are left to identify with the adventures and imaginative stories of white characters amid white settings. Aptly characterized as an, “apartheid of children’s literature,” two moving first-person accounts from Walter Dean Myers and Christopher Myers detail the significance of incorporating more characters of color for all readers. One major effect of this dearth of representation, according to Christopher Myers,

…is a gap in the much-written-about sense of self-love that comes from recognizing oneself in a text, from the understanding that your life and lives of people like you are worthy of being told, thought about, discussed and even celebrated.

Just as significant, is the number of children’s books about Latino children from the 2013’s trove of 3,200 books: 53. That’s 5-3. As a reminder, the United States Census tallied 53 million Latinos in the United States, representing the nation’s youngest demographic (children!).

However, perhaps worse than the actual lack is the rise of stereotypic in-your-face representations of race within children’s books – award-winning ones, actually – and their role in teaching children troubling ideas about race, language, and “difference.”

My name is Skippito Friskito. (clap-clap)

I fear not a single bandito. (clap-clap)

My manners are mellow,

I’m sweet like the Jell-O,

I get the job done, yes indeed-o.

Case in point: Skippyjon Jones, a Siamese cat that pretends to be a Chihuahua superhero. Skippyjon speaks English, but his super hero alter ego speaks in Mock Spanish in his recurring and imaginative quests. Speaking “Spanish” in hyperanglized fashion recasts Skippyjon from an English-speaking (white) cat to a Spanish-accented (brown) dog. His auditory performance of Mexicanness, what Reina Prado considers “sonic brownface,” reeks of white privilege as he code-switches from cat/white/English to dog/brown/”Spanish.” What’s worse, as a children’s book, directed at those between the impressionable ages of 4-8, Skippyjon encourages both adult readers and young readers to read out loud and perform sonic brownface. Listening to the book’s trite word choice (amigos, adios, frijoles), fake Spanish (indeed-o, mask-ito) and embellished accents (“ees” for is) trains the ear on how to speak “Mexican,” presumably, of course, for the listening amusement of non-Mexicans.

Image by Flickr user Howard Lewis Ship

“I am El Skippito, the great sword fighter,” said Skippyjon Jones.

Apparently, these tried and true tactics sell quite well. This award-winning children’s book character, by Judy Schachner, has spawned into a lucrative empire that includes fourteen books, a coordinating plush toy figure, online webisodes of the books’ stories, CDs of Schachner reading out loud, the obligatory Ipad app, a starring role in the department store Kohl’s “We Care” charity campaign in 2012, and get this, a children’s musical. Of course, Skippyjon is not really recognized as a book series about Latinos (like fellow television darlings, Dora the Explorer, Handy Manny, or Dragon Tales) yet it taps into every flinching stereotype we know of, and should avoid, about Mexicans. Equating Mexicans and Mexican tales to the canine of a Chihuahua is hardly new but it does not make it less problematic.

For instance, in the inaugural self-titled Skippyjon Jones book, the cat’s adventures take place “far, far away in old Mexico.” Much like the perpetual placement of African Americans in the past tense within children’s books, situating Mexico in the imaginative past reinforces perceptions of all-things-Mexican as distant, foreign, and old. Skippyjon and his chimichangos – his sidekicks (good guys) –set out to save their rice and beans from Alfredo Buzzito and Bumblebeeto Bandito (bad guys). Zorro-esque masks, swords, fiestas followed by siestas, fellow Chihuahuas, piñatas, plenty of cacti, and lots of clap-clap cues frame the rice-and-bean rescue. His adventures, book after book, via a Skippito brown identity sends a disquieting message about power and privilege. Skippito, even when masked, still plays the role of Great White Hero to the masses of “Mexican” dogs.

Image by Flickr user Tomas Quinones

Then all of the Chimichangos went crazy loco.

Several of Schachner’s Skippyjon books have received notable accolades including, for instance, the 2004 E.B. White Read Aloud Award and a spot on the coveted “Teachers’ Top 100 Books for Children” by the National Education Association in 2007. The former comes with an adorning gold seal on future editions of honored books. A sampling of the series’ laudatory press, from the E.B White Read Aloud press release, “Peppered with Spanish expressions and full of energized fun, SkippyJon Jones is not only entertaining for the listener, it’s also enjoyable for the reader.” And from the author’s webpage: “Each of my adventures are ay caramba, mucho fun but they’re educational too!” The insinuation that the Skippyjon Empire teaches Spanish not only ignores the richness of Spanish but it also feeds popular ideals that Spanish is an “easy” and “fun” language to learn.

Schachner’s recurrent use of “Spanish,” in particular, not only structures the silly narrative adventures of Skippyjon as he imagines himself to be Skippito but the racialized language play has also become the hallmark element of Skippyjon. Written and read out loud by parents and teachers, some of Skippyjon’s signature phrases include “Holy Guacamole!” and “Holy Frijoles!” – textbook examples of Jane Hill’s renowned writings on Mock Spanish (or fake, incoherent Spanish uttered and deemed “funny” by non-native Spanish speakers). Because we already hold native Spanish-speakers (U.S. Latinos) with such little regard in the first place, Mock Spanish done for laughs, as argued by Hill, comes quite easily. Carmen Martínez-Roldán takes the Skippyjon Jones series to task in necessary detail; see her analysis of Mock Spanish in the equally troubling, Skippyjon Jones in the Doghouse. Her emphasis on the cultural representations of Mexicans vis-a-vis language in children’s books supports my tirade against this cat/dog. Martínez-Roldán found that several teachers, particularly those from the Southwest, expressed a sense of inexplicable uneasiness to these books. Amazon ratings are (painfully) positive for Skippyjon, yet, according to Martínez-Roldán, those who expressed low ratings were “accompanied by lengthy explanations, mostly related to misrepresentations of Mexicans and the poor use of Spanish.” Her research calls for more diversity within children’s literature but, central to this essay, reminds us that U.S. Latinos hold both a personal and political relationship to Spanish.

Image by Flickr User John Graham

Anthropologist Bonnie Urciuoli explains how Spanish, when overheard in designated public spaces (think: Cinco de Mayo or Mexican restaurants) is safely “ethnified,” yet Spanish is regarded as out of place or “racialized” when heard as bilingual announcements at local grocery stores or school sites. When heard by monolingual English speakers outside of its designated spaces in the U.S., Spanish carries “racialized” connotations such as “impoliteness” and “danger.” The insistence many American employers place on speaking English and prohibiting non-English language conversations at workplaces, for instance, speaks to the public boundaries imposed on Spanish and Spanish-speakers. (Yes, Whole Foods. I am looking at you.)

Jane Hill’s provocative argument, built from Uricuolli’s writings, examines Whites’ use of Spanish (Mock Spanish). Unlike Latinos, who learn early on to self-monitor where and how they speak English and Spanish, non-native speakers of Spanish do not carry this same burden, according to Hill. In fact, they have the privilege of speaking grammatically incorrect Spanish, in hyper Anglicized Spanish, or mockingly (by adding a stupid “o” or prefacing a phrasing with “el”) without surveillance.

Then, using his very best Spanish accent, he said, “My ears are too beeg for my head.

My head ees too beeg for my body. I am not a Siamese cat… I AM A CHIHUAHUA!”

In addition to overplayed colloquial expressions, Schachner demarcates a racial line with “visual accents” (“beeg” for big) (see Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman, Priscilla Peña Ovalle and Sara V. Hinojos). In line with Uricuolli’s ideas, even Skippito’s English is accented and marked while in “Mexican” character. Readers stammer through “ees” and “beeg” in an effort, as prepped, to use their “very best Spanish accent.” The practice teaches children that accents are performative and easy to take on and off rather than hear accents as indicative of someone’s larger family histories of migration and culture.

The Frito Bandito, Image by Flickr user Bill Futreal

For children unfamiliar with Mexicans and Latinos, these books cast Spanish with archaic imageries of Mexican bandits and modern-day Frito Banditos. Spanish is not used as a language to communicate given its incoherence. Instead, Schachner uses Spanish to laugh at Skippito and by extension, Mexicans and Latinos in the U.S.; its runaway success is indicative of how “funny” Spanish and Mexicans continue to be to White and/or monolingual English speakers.

For Latinos, these books plant early attitudes about their own language differences. For children positioned as the family translator or struggling to maintain a bilingual, bicultural existence, these books teach children to shun their accent and those of their families. These books are clearly not for my two kids, whose young ears are already familiar with their grandmother’s Spanish-accented English and their own mother’s English-accented Spanish.

“Vamos, Skippito- or it is you the Bandito will eato!”

Reading children’s books out loud and listening to race through scripted accents sends troubling messages about “difference” at an early age. Educators have long argued that children’s books serve as both mirrors and maps to affirm and inspire readers’ identities, experiences, and future motivations. True. But I would also argue that the woeful absence of more diverse children’s tales mirrors a number of campaigns directed at working-class, communities of color; namely, our nation’s shaky commitment to universal preschool, lack of public support for Women Infant and Children (WIC) and Food Stamp programs, and outdated approaches to parental leaves (six measly weeks). In particular, Skippyjon Jones is a kid’s rendition of grownup racial and language politics, a pint-size version of NAFTA and English-only propositions presented for five-year old audiences. These policies, like the woeful crop of contemporary books, do little to provide a map for the livelihoods of children of color. Instead, Skippyjon’s use of language, a reincarnation of Speedy Gonzalez normalizes English, white characters (even in brown drag), and helps keep Cinco de Mayo antics alive.

Image by Flickr user Manchester City Library

—

NOTE: On 5-8-14, the author added a passage to this article to reflect the relationship of her work to Carmen M. Martínez-Roldán’s “The Representation of Latinos and the Use of Spanish: A Critical Content Analysis of Skippyjon Jones” published in The Journal of Children’s Literature (2013).

Featured Image by Flickr user The Long Beach Public Library, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

—

Dolores Inés Casillas is an assistant professor in the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies and a faculty affiliate of Film & Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She writes and teaches courses on Latina/o sound practices, popular culture, and the politics of language. Her book, Sounds of Belonging: U.S. Spanish-language Radio and Public Advocacy will be published this fall by New York University Press as part of their Critical Cultural Communication series.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

This Is How You Listen: Reading Critically Junot Díaz’s Audiobook-Liana Silva

Óyeme Voz: U.S. Latin@ & Immigrant Communities Re-Sound Citizenship and Belonging -Nancy Morales

Sonic Brownface: Representations of Mexicanness in an Era of Discontent–reina alejandra prado saldivar

Recent Comments