What is a Voice?

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? In today’s post, Alexis Deighton MacIntyre explores society’s interpretations of voicing, sounding and listening. Inspired by Christine Sun Kim and Evelyn Glennie, Alexis advocates for understanding voicing as movement and rhythm instead of strictly articulated sound. – SO! Intern Kaitlyn Liu

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? In today’s post, Alexis Deighton MacIntyre explores society’s interpretations of voicing, sounding and listening. Inspired by Christine Sun Kim and Evelyn Glennie, Alexis advocates for understanding voicing as movement and rhythm instead of strictly articulated sound. – SO! Intern Kaitlyn Liu

The following post is a companion to Alexis’ voicings essay published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies 3.2.

What is a voice, and what does it mean to voice?

Definitions of the voice may be pragmatic: working titles that depend in part on their institutional basis within ethnomusicology, literature, or psychoacoustics, for example.

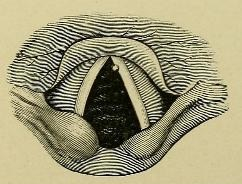

“Autoscopy of the larynx and trachea” by Flickr user Medical Heritage Library Inc.

Or, to take another strategy, voice is given by an impartial biological framework, a respiratory-laryngeal-oral assembly line. Its product, an acoustic signal, is transmitted via material vibration to an ear, and then a brain. The mind of a listener is this system’s endpoint. Although this functional description may smack of scientific reductionism, the otolaryngeal voice often stands in for embodiment in humanist discourse.

For Adriana Cavarero, the voice means “sonorous articulation[s] that emit from the mouth” (Caverero 2005, 14), involving “breath” and “[w]et membranes and taste buds” (134). Quoting Italo Calvino, she affirms that “a voice involves the throat, saliva.” According to Brandon Labelle, the mouth is “wrapped up in the voice, and the voice in the mouth, so much so that to theorize the performativity of the spoken is to confront the tongue, the teeth, the lips, and the throat” (Labelle 2014, 1). In Labelle’s view, orality is in fact overlooked, “disappearing under the looming notions of vocality” (8), such that his contribution to voice studies is to “remind the voice of its oral chamber” (4). Conclusions such as these inform our subsequent theoretical, methodological, and political theories of both voicing and listening.

Cavarero and Labelle are right to address the erasure of speaking and listening in Western intellectual history. However, to take for granted that voice is always audible sound, always sounded by a certain system, is to make the case for a fragmented brand of vocal embodiment. Rosi Braidotti terms this “organs without bodies”, and her critique of “instrumental denaturalisation,” whereby biotechnology transforms the body “into a factory of detachable pieces,” could also apply to the implicit processes by which discourse delineates the voice (Braidotti 1994, 59).

“Intersectional Souls” by Flickr user Makoto Sasaki

Yet, a priori constructs like “voice is sound” or “sound is [audibly] heard” have not gone unchallenged. For instance, scholars, artists, and musicians who engage with disability or Deafness resist or redefine taxonomies that ignore or distance other ways of voicing, sounding, and listening. Sarah Mayberry Scott blogs in SO! about the work of Christine Sun Kim, for example, whose performative practice reimagines Western musical norms through a Deaf lens. Kim’s uses of subsonic frequencies and face markers are two of many interventions by which she “reclaims sound” from an aural-centric worldview—not just for herself and other Deaf people, but for all bodies. Indeed, Kim invites hearing people to see and feel familiar social and environmental sounds, to rediscover inaudible channels for themselves, a praxis Jeannette DiBernardo Jones calls the “multimodality of hearing deafly” (DiBernardo Jones 2016, 65)

To hear deafly is thus to enter an expanded field of sound. The same is true of voicing deafly. Kim negotiates her audible voice by “trying on” interpreters, “guiding people to become [her] voice”, and by “leasing” out her own or “borrowing” another’s. But there are also features common to both spoken and signed voices that risk being lost to the spotlight of audition.

Face Opera with Christine Sun Kim as part of the Calder Foundation’s “They May As Well Have Been Remnants of the Boat”

For instance, spontaneous speech occurs with concurrent face, torso, arm, and hand movements. These voicing actions unfold in tight synchrony with words, sighs, and facial expressions. In the case of beat gestures, the “meaningless” strokes made with the hands, they are in fact temporally precedent to stressed syllables; that is, manual prosody is perceptually paired with vocal prosody, but materialises a fraction of a second earlier. When psychologists subtly perturb gestures in the hand, they record analogous effects in oral production. This hand-mouth network is even more evident in some non-Western hearing cultures that also use sign language, where distinguishing between spoken and gestured dialogue is both impractical and nonsensical. Taken together, it seems that the body distributes the voice, neither knowing nor caring for its own discursive fencings.

If gesture is a proprioception, or action-form, of vocality, haptic sensation is another way to hear. In her vibrational theory of music, Nina Sun Eidsheim argues that sound is not a static noun, but a process, such that the so-called musical object—or, indeed, any sonic figure—resists stable definition, but is rather contingent on the myriad ways of experiencing material pulsation. Via air, water, architecture, or people, the oscillatory basis of Eidsheim’s framework disrupts not only the divisions of labour amongst the Cartesian senses, but also those between sound, sound producer, and listener—unity from propagation. Such vibrations can be all-consuming, rendering the body, in Evelyn Glennie’s words, as “one huge ear.” They can also lurk, near the bass-end of traffic, or remain as a trace, as in dubstep, whose shuddering basslines connote tactility. Alluding to the scene’s origins in Jamaican sound system, the “wub” effect is the auditory fetishization of equipment failure, the resounding noise of a speaker pushed to uncontrolled, uncontainable movement.

In her TED Talk, Kim explains that “in Deaf culture, movement is equivalent to sound.” A feature common to most human movement is rhythm, the temporal patterns that emerge in speaking, walking, chewing, typing, weaving, hammering. As the banality of these actions suggests, rhythm permeates throughout everyday life. We join our rhythms in a process known to cognitive sciences as entrainment. Sunflowers entrain their circadian cycles to anticipate the path of the sun, fireflies entrain their flashes at a rate determined by species membership, and grebes, dolphins, and humans (among other animals) entrain their social actions. Neuroscientists theorize that even our neurons entrain to another’s speech, either spoken or signed. Simply put, entrainment is being together in time with someone, or some entity, sharing in a temporal perspective. So quotidian is the state of being entrained that we may not notice when we fall into step with a friend or anticipate our turn in a conversation. But it would not be possible without rhythm, which is both a shared construct through which we time our gestures sympathetically, and a sign of subjectivity, an identifier, a distinctive feature by which we can recognise ourselves or another.

Christine Sun Kim’s musical interpretation of the sign for the words “all night”

Rhythm could therefore form yet another (in)audible nexus within a relational definition of the voice, whose sites could include the larynx, face, hands, cochlea, and on and under the skin, in addition to various inorganic materials. In conversation with John Cage, the hearing composer Robert Ashley considered “time being uppermost as a definition of music,” music that “wouldn’t necessarily involve anything but the presence of people” (Reynolds, 1961). Although Ashley’s “radical redefinition” is stated in temporal terms, the concepts of time, rhythm, and movement are not easily disentangled. Plato explains rhythm as “an order of movement”, while for Jean Luc Nancy, rhythm is the “time of time, the vibration of time itself” (Nancy 2009, 17). As a cycle that is propagated through the medium of entrained bodies, rhythm may well be just another vibration, one suited to Eidsheim’s multisensory groundwork of tactile sound. As with music, the voice need not be “stable, knowable, and defined a priori” (Eidsheim 2015, 22), but dynamic, chimerical, and emergent. Speaking, slinking, signing, swaying—indeed, all our actions, gestures, and locomotions constitute us. Crucially, it is not what we move, but how we move, that is vocal.

_

Featured Image: “Vocal” by Flickr user ArrrRRT eDUarD

_

Alexis Deighton MacIntyre is a musician and PhD candidate in cognitive neuroscience at University College London, where she’s currently researching the control of respiration during rhythmic motor activities, like speech or music. Formerly, she studied cognitive science and music at University of Cambridge and Vancouver Island University. You can follow her on Twitter at @alexisdeighton or read her science blog at https://alexisdmacintyre.wordpress.com/

_

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Plasticity of Listening: Deafness and Sound Studies – Steph Ceraso

Re-Orienting Sound Studies’ Aural Fixation: Christine Sun Kim’s “Subjective Loudness” – Sarah Mayberry Scott

Mr. and Mrs. Talking Machine: The Euphonia, the Phonograph, and the Gendering of Nineteenth Century Mechanical Speech – J. Martin Vest

On “The Dream Life of Voice:” A Rerecording of Bernadette Mayer Reading from The Ethics of Sleep – John Melillo

This is not new to me. Both my artistic work and a number of my scholarly works have been purposely ignored or undermined in previous occasions, perhaps due to my non-white, non-European background and epistemology. During the assessment of my doctoral dissertation in a well-known Scandinavian University, for example, the three-member committee harshly attacked the very foundations of my project because of my claim that case studies in Indian cinema could produce important new knowledge in the field of sound studies, media art and film history. However, Indian cinema, the largest producer of films in the global industry, is equally a part of world cinema as European and American cinemas, and studying its sound production would indeed add dimensions to the field of sound studies. Their resistance towards my object of study implied that choosing European cinema would immediately make my hypotheses acceptable.

This is not new to me. Both my artistic work and a number of my scholarly works have been purposely ignored or undermined in previous occasions, perhaps due to my non-white, non-European background and epistemology. During the assessment of my doctoral dissertation in a well-known Scandinavian University, for example, the three-member committee harshly attacked the very foundations of my project because of my claim that case studies in Indian cinema could produce important new knowledge in the field of sound studies, media art and film history. However, Indian cinema, the largest producer of films in the global industry, is equally a part of world cinema as European and American cinemas, and studying its sound production would indeed add dimensions to the field of sound studies. Their resistance towards my object of study implied that choosing European cinema would immediately make my hypotheses acceptable. In his essay “

In his essay “

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Recent Comments