SO! Reads: David Novak’s Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation

We are living in strange times. Our experiences, especially our musical experiences, have become fragmented and odd. The album has been declared dead, live concerts are now silent, listened to on headphones, and some of our favorite performers exist in a faux-holographic space between life and death. The fragmentation of our musical experiences is indicative of a larger set of changes that encourage sound studies to pay attention to fragmented, outlying, and diffuse sonic phenomenon. In his new book Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation, part of Jonathan Sterne and Lisa Gitelman’s “Sign, Storage, Transmission” series at Duke University Press, David Novak pays attention to one such fragmented and outlying realm, Noise music. Novak’s contribution to sound studies is to encourage us to deal with the fragmented complexity of sonic environments and contexts, especially those where noise plays a crucial part.

We are living in strange times. Our experiences, especially our musical experiences, have become fragmented and odd. The album has been declared dead, live concerts are now silent, listened to on headphones, and some of our favorite performers exist in a faux-holographic space between life and death. The fragmentation of our musical experiences is indicative of a larger set of changes that encourage sound studies to pay attention to fragmented, outlying, and diffuse sonic phenomenon. In his new book Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation, part of Jonathan Sterne and Lisa Gitelman’s “Sign, Storage, Transmission” series at Duke University Press, David Novak pays attention to one such fragmented and outlying realm, Noise music. Novak’s contribution to sound studies is to encourage us to deal with the fragmented complexity of sonic environments and contexts, especially those where noise plays a crucial part.

The past decade has seen growing public attention to noise as pollution, as problem, and as a poison. Examples of noise as a social issue needing immediate response abound, but one letter to the editor from the Wisconsin Rapid Tribune epitomizes the way that noise is sometimes read as a problem to be overcome. Novak’s book is one a few recent books, including Eldritch Priest’s Boring Formless Nonsense, Greg Hainge’s Noise Matters, and Joseph Nechvatal’s Immersion Into Noise, that complicate the idea of noise as problem. What sets Novak’s book apart from these is how his ethnographic approach allows him to approach Noise music from both the macro-perspective of its historical context and the micro-lens of his personal relationship to it.

For Novak, Noise music is a trans-cultural, transnational interaction that is both material and abstract. His analysis of it works to blur the boundary between both large-scale networks of exchange and the highly individuated experience. Novak relates the story of Noise music as originating in Japan in the 1980s. Noise musicians working separately caught the ears of American fans. Some of these fans were well-known musicians themselves, who brought Noise recordings and eventually the performers themselves to a wider U.S. audience. At the time, Noise was generally understood as taking one of two binary positions. Either Noise music was understood as a uniquely Japanese cultural expression, or it was instead theorized as a product of the Western imaginary motivated by the production of Japan as the anti-subject within modernity (24). Novak wisely recognizes the limited nature of these two positions, and seeks a more sophisticated method of understanding the circulation that creates Noise music, contributing, ultimately, a theory of feedback. Here the transnational circulation of materials, ideas, and expressions constitutes a culture itself, one that is not distinct from either the Japanese or the U.S. manifestations of Noise music (17). This a welcome contribution to compositional and intersectional perspectives on cultural exhange.

For Novak, Noise music is a trans-cultural, transnational interaction that is both material and abstract. His analysis of it works to blur the boundary between both large-scale networks of exchange and the highly individuated experience. Novak relates the story of Noise music as originating in Japan in the 1980s. Noise musicians working separately caught the ears of American fans. Some of these fans were well-known musicians themselves, who brought Noise recordings and eventually the performers themselves to a wider U.S. audience. At the time, Noise was generally understood as taking one of two binary positions. Either Noise music was understood as a uniquely Japanese cultural expression, or it was instead theorized as a product of the Western imaginary motivated by the production of Japan as the anti-subject within modernity (24). Novak wisely recognizes the limited nature of these two positions, and seeks a more sophisticated method of understanding the circulation that creates Noise music, contributing, ultimately, a theory of feedback. Here the transnational circulation of materials, ideas, and expressions constitutes a culture itself, one that is not distinct from either the Japanese or the U.S. manifestations of Noise music (17). This a welcome contribution to compositional and intersectional perspectives on cultural exhange.

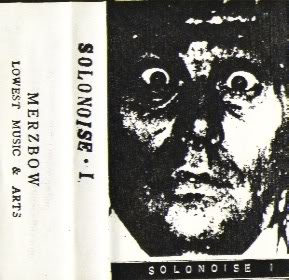

If Noise music is a circulation, a set of experiences and contexts, flows and scapes, ecologies and environments, then genre boundaries can not adequately describe the contextual and historical exchange of sound. Though genre must be considered, Japanoise does not find Novak searching particularly rigorously. He chooses two key Noise musicians, The Nihilist Spasm Band from Canada and Merzbow from Japan and describes their historical context, reception, and influence. But other than those descriptive basics, he is unsuccessful in finding anything new to say about Noise as genre. Concluding the chapter, he casually states that the existence of Noise threatens the boundaries of other musical genres. Though this fascinating statement would have been worthy of a chapter, and certainly foundational to his central idea (that Noise music is diffuse), Novak misses an opportunity to better support these connections in his chapter on genre.

Most interesting, however, is Novak’s focus on the material conditions of the production of Noise music. In describing the diffuse flows and scapes of Noise music, he addresses a plurality of experience: from the technological to the spatial to the private dimensions of listening. These concerns put him in conversation with Louise Meintjes’ Sound of Africa and Julian Henriques’ Sonic Bodies. Like these scholars, Novak refuses to locate the material conditions of production as solely economic, technological, or cultural. Instead, Noise music results from of an assemblage of conditions and possibilities. This is best exemplified by how Novak distinguishes the live music experience from the recorded. Here, Novak resists the neat distinction, long established in musicology, that hears the live experience as collective and interactive, and recorded music as individuated and passive. Instead, Novak suggests “liveness” and “deadness.” Liveness and deadness are not bounded to the dichotomy of the live performance with the recording, but rather two qualities that float through and with both experiences. “Liveness is about the connection between performance and embodiment… deadness, in turn, helps remote listeners recognize their affective experiences…” The experience of live Noise music, according to Novak, often challenges the boundaries of what is often expected when hearing live music. I have seen this in my own experiences standing in an audience surrounded by shrieking, booming, droning noises.

Truth be known, I’m as taken with Noise music as Novak. If his book confesses to being written by a critical but vehement fan, then I ought to confess the same of the music which I love so dearly. I had the chance to see Merzbow perform in Raleigh in August. He strummed obviously homemade instruments, turned fader pots, and concentrated intently on his laptop. A fan was crawling through the crowd on their hands and knees; occasionally they stood to sway, then returned to crawling. I thought that this behavior might seem odd, but in the context of Merzbow’s performance, it was as legitimate as any other. Through these odd behaviors, the fan demonstrated Novak’s conception of individuation within Noise music. The material conditions of the performance, the screeching Noise, made it impossible for me to ask the person what they were doing or feeling. I experienced the fan and the Noise in a tension from which there is no resolution. We were both uncomfortably located in a multiplicity of experiences. These experiences don’t resolve to a whole, but rather pulsate and echo and feed back into each other, intertwining with expectations of behavior, material conditions, and embodiment(s).

Japanoise raises many important questions. What social processes lead us to foreground the sonic experiences in our lives? And further, how does a critical understanding of these processes help to advance the work of understanding the power and politics of sound? But, for me, Novak’s work serves best to remind me of how much value is found in fragmented, diffuse, outlier experiences, like Noise music. Because sound occupies a crucial role in our social and political lives, Novak encourages us not to resolve tensions, rather to exist amongst them and hear them as lively and productive.

For those readers who might be unfamiliar with the music Novak describes, the book’s website has a fantastic collection of supplemental media for you to enjoy: http://www.japanoise.com/media/.

–

Seth Mulliken is a Ph.D. candidate in the Communication, Rhetoric, and Digital Media program at NC State. He does ethnographic research about the co-constitutive relationship between sound and race in public space. Concerned with ubiquitous forms of sonic control, he seeks to locate the variety of interactions, negotiations, and resistances through individual behavior, community, and technology that allow for a wide swath of racial identity productions. He is convinced ginger is an audible spice, but only above 15khz.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Tofu, Steak, and a Smoke Alarm: The Food Network’s Chopped & the Sonic Art of Cooking–Seth Mulliken

SO! Reads: Jonathan Sterne’s MP3: The Meaning of a Format–Aaron Trammell

The Noise of SB 1070: or Do I Sound Illegal to You?–Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman

Trackbacks / Pingbacks