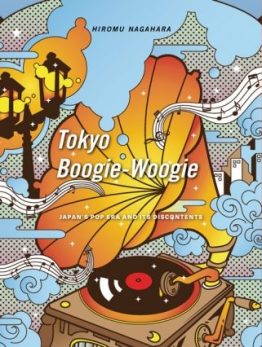

SO! Reads: Hiromu Nagahara’s Tokyo Boogie-Woogie: Japan’s Pop Era and Its Discontents

When times are tough and people are feeling sad, they might need space to be calm, to reflect, and to heal. For example, in the United States following September 11, 2001, Clear Channel (now iHeartMedia) suggested keeping a number of “aggressive” artists, such as Rage Against the Machine and AC/DC, off the airwaves for a while to provide the nation with one group’s version of a calming sonic space. However, this suppression couldn’t hold; at a certain point, the pilot light re-ignited, and Americans wanted to turn the gas up high, to feel the heat, to extravagantly combust themselves out of the Clear Channel rut. Explosive tracks followed those tragic times in 2002–from Missy Elliott’s “Lose Control” to DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s “Turn Down for What” to Miley Cyrus’ “We Can’t Stop” to Daft Punk’s “Lose Yourself to Dance”–resonating over the airwaves and web browsers and dance floors. So whose idea of a healing sonic space prevails? For how long? Who decided what healing looks and sound like? And who decides the time for healing is finished?

When times are tough and people are feeling sad, they might need space to be calm, to reflect, and to heal. For example, in the United States following September 11, 2001, Clear Channel (now iHeartMedia) suggested keeping a number of “aggressive” artists, such as Rage Against the Machine and AC/DC, off the airwaves for a while to provide the nation with one group’s version of a calming sonic space. However, this suppression couldn’t hold; at a certain point, the pilot light re-ignited, and Americans wanted to turn the gas up high, to feel the heat, to extravagantly combust themselves out of the Clear Channel rut. Explosive tracks followed those tragic times in 2002–from Missy Elliott’s “Lose Control” to DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s “Turn Down for What” to Miley Cyrus’ “We Can’t Stop” to Daft Punk’s “Lose Yourself to Dance”–resonating over the airwaves and web browsers and dance floors. So whose idea of a healing sonic space prevails? For how long? Who decided what healing looks and sound like? And who decides the time for healing is finished?

Hiromu Nagahara is a historian who has examined how music was used during a transformative era in Japanese history. Nagahara’s book, Tokyo Boogie-Woogie: Japan’s Pop Era and Its Discontents (Harvard UP, 2017), focuses on the ryūkōka popular music produced “primarily between the 1920s and the 1950s” (3), which is different from the hayariuta music of the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taishō (1912-1926) periods or the kayōkyoku ballad songs post-1970. One of Nagahara’s central concerns with popular music is how it furthered the nation-building endeavor of the 1920s and 1930s. Another concern is how censorship was implemented and policed through the wartime era and beyond. Nagahara’s stance on censorship in Japan is that state powers such as the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (Nihon Hōsō Kyōkai, NHK), public powers such as music critics, and self-censorship are responsible for the limitations put on artistic productions. This stance is in concert with scholars such as Jonathan Abel and Noriko Manabe, although unfortunately Nagahara’s book doesn’t discuss Manabe’s work on the censorship of music addressing the Daiichi Fukushima disaster.

Hiromu Nagahara is a historian who has examined how music was used during a transformative era in Japanese history. Nagahara’s book, Tokyo Boogie-Woogie: Japan’s Pop Era and Its Discontents (Harvard UP, 2017), focuses on the ryūkōka popular music produced “primarily between the 1920s and the 1950s” (3), which is different from the hayariuta music of the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taishō (1912-1926) periods or the kayōkyoku ballad songs post-1970. One of Nagahara’s central concerns with popular music is how it furthered the nation-building endeavor of the 1920s and 1930s. Another concern is how censorship was implemented and policed through the wartime era and beyond. Nagahara’s stance on censorship in Japan is that state powers such as the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (Nihon Hōsō Kyōkai, NHK), public powers such as music critics, and self-censorship are responsible for the limitations put on artistic productions. This stance is in concert with scholars such as Jonathan Abel and Noriko Manabe, although unfortunately Nagahara’s book doesn’t discuss Manabe’s work on the censorship of music addressing the Daiichi Fukushima disaster.

Nagahara greatly contributes to the English-language scholarship on Japanese music critics; those interested in how Theodor Adorno similarly addressed German sociopolitical issues through music criticism will find both the parallels and the divergences mapped in Nagahara’s work fascinating. The biggest takeaway for this reader, however, was the book’s tracing of Japan’s shifting class formations through these decades. Nagahara shows that Japan evolved from an infamously strict class-caste system into a middle-class society into a society that “increasingly saw itself to be classless” (212) all in the span of a century, and that music and the nation’s burgeoning media industry played pivotal roles in this transformation.

Movie Poster for Tokyo March, 1929, wikimedia commons

Specifically, Nagahara argues that the commercialization and industrialization of music in Japan were natural outcomes of the nation’s shift toward capitalism in the Meiji period. While the “gradual transformation of music, and art in general, into ‘consumer goods’” (64) in Germany signaled the “long-term decline of German middle-class culture” for Theodor Adorno, it actually signaled the opposite for Japan. Nagahara notes that, prior to the Meiji period, the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868) “idealized and mandated the separation of different status groups – in particular the division between members of the ruling samurai class and those who were deemed to be ‘commoners’” (21). Therefore, when the Japanese public bought an unprecedented 150,000 copies of “Tokyo March” (“Tokyo kōshinkyoku”) in 1929 and when records produced in 1937 were selling half a million, it became clear that “luxury goods” (18) such as phonographs and records were no longer simply for the ruling elites of Tokugawa-era wealth. Instead, Japan’s former commoners were marching toward capitalism with a middle-class cultural dream on the horizon.

As a period study, Nagahara doesn’t try to tie things up nicely – that’s not often how history works. As such, Nagahara concerns himself with the politicization of media in Japan, and he extends his discussion of pre-war popular music up through the 2000s with quick references to Pokémon and AKB48. However, there is a missed opportunity here in that Nagahara never references the Daiichi Fukushima disaster and the subsequent outpouring of popular music that responded to the public and private-sector management of the catastrophe.

This would have fit perfectly in the “The Television Regime” subsection of the book’s conclusion, and it would have added greatly to what Nagahara recognizes is a “significant dearth of scholarly analysis of the inner workings of popular song censorship in the last decades of the twentieth century” (218) and beyond. This reader would be excited to read more by Nagahara if he were to take up this task. I learned so much about the context and reception of pop music in Japan from Tokyo Boogie-Woogie, and this book would help any reader better understand one of the largest and most influential music and media scenes in the world today.

—

Featured Image: “Vintage Hi-Lite Transistor Radio, Model YTR-601, AM Band, 6 Transistors, Made In Japan, Circa 1960s” by Flickr User Seah Haupt, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Shawn Higgins is the Academic Coordinator of the Undergraduate Bridge Program at Temple University’s Japan campus. His latest publication is “Orientalist Soundscapes, Barred Zones, and Irving Berlin’s China,” coming out in the 2018 volume of Chinese America: History and Perspectives.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Reads: Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder’s Designed For Hi Fi Living–Gina Arnold

SO! Reads: Susan Schmidt Horning’s Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP— Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo

SO! Reads: Jonathan Sterne’s MP3: The Meaning of a Format–Aaron Trammell

Trackbacks / Pingbacks