Y2K, Collective Ritual, and Sound in the New Millennium

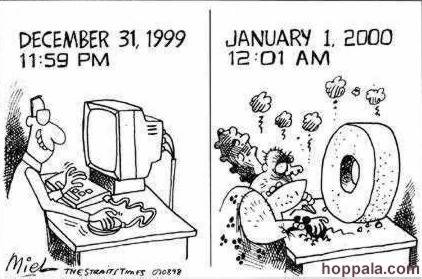

The recent New Year brought back some slightly embarrassing memories of past ball-droppings, 1999 in particular. That was the year, you’ll remember, when the world as we know it was to end due to all the clocks in all computers reading 0000 instead of 2000 – nuclear plants were to implode, bank accounts would be scrambled and a month later, the world would resemble some scene from The Road Warrior. I’ll fess up. I bought into the Y2K hype hook-line-and-sinker. I hunkered down in my living room with some old friends playing Risk that New Year’s Eve, I awaited an event of cataclysmic proportions. As the countdown droned on TV, it seemed every dice roll took me one step closer to the end . . . 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. Upon zero, nothing changed and anxiety slowly began to leak from my body. Sting appeared on TV and introduced the new millennium with his jazzy “Brand New Day.” With lyrics about time and second chances, I grew to associate the song with a sense of profound relief. No matter how hokey Stings lyrics were (he uses the term “fuddy-duddy” at one point), “Brand New Day” will forever remind me of second-chances and possibility. Part of a clever advertising coup designed to reinvigorate Sting’s flagging career, the gospel tropes used in “Brand New Day” fit as a discursive response to the apocryphal (and apocalyptic) conversations circulating about Y2K at the time.

The recent New Year brought back some slightly embarrassing memories of past ball-droppings, 1999 in particular. That was the year, you’ll remember, when the world as we know it was to end due to all the clocks in all computers reading 0000 instead of 2000 – nuclear plants were to implode, bank accounts would be scrambled and a month later, the world would resemble some scene from The Road Warrior. I’ll fess up. I bought into the Y2K hype hook-line-and-sinker. I hunkered down in my living room with some old friends playing Risk that New Year’s Eve, I awaited an event of cataclysmic proportions. As the countdown droned on TV, it seemed every dice roll took me one step closer to the end . . . 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. Upon zero, nothing changed and anxiety slowly began to leak from my body. Sting appeared on TV and introduced the new millennium with his jazzy “Brand New Day.” With lyrics about time and second chances, I grew to associate the song with a sense of profound relief. No matter how hokey Stings lyrics were (he uses the term “fuddy-duddy” at one point), “Brand New Day” will forever remind me of second-chances and possibility. Part of a clever advertising coup designed to reinvigorate Sting’s flagging career, the gospel tropes used in “Brand New Day” fit as a discursive response to the apocryphal (and apocalyptic) conversations circulating about Y2K at the time.

The history of technology is filled with utopian and dystopian visions of the future. Famously depicted in Apple’s “1984” commercial, the technocratic American narrative (Think Reaganomics) goes something like this: While developments in technology can allow for an increased sense of autonomy and individuality, they are unerringly used for evil. This evil strongly resembles a stereotypical Soviet culture where individuality is sacrificed for the good of the collective whole. Therefore, good technology promotes the individual while evil technology supports the collective.

If this seems a little heavy handed, it should be noted that the whole endeavor of mass computing has its roots in American Cold War history. After the atomic catastrophes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Vannevar Bush, then Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, predicted the Internet with the “memex machine” in his article to The Atlantic, “As We May Think.” Written to an unassuming audience, Bush suggests the destructive potential of atomic weaponry heralded a concrete limit to traditional methods of warfare, because of this the next battlefronts would be informatic. Y2K is a dystopic variation on this theme, atomic blow up by-way-of nuclear power had even become incorporated into some of its myths. These myths were a fantasy, to be sure, but they were rooted in the collective fears of a confused and dysphoric America, an America which had recently overcome Communism and lauded its rapidly developing technological sector as a new source of economic capital on the world stage. Y2K was scary because it played on a cultural fear of technology, which was paradoxically one of America’s key exports at the time.

If this seems a little heavy handed, it should be noted that the whole endeavor of mass computing has its roots in American Cold War history. After the atomic catastrophes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Vannevar Bush, then Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, predicted the Internet with the “memex machine” in his article to The Atlantic, “As We May Think.” Written to an unassuming audience, Bush suggests the destructive potential of atomic weaponry heralded a concrete limit to traditional methods of warfare, because of this the next battlefronts would be informatic. Y2K is a dystopic variation on this theme, atomic blow up by-way-of nuclear power had even become incorporated into some of its myths. These myths were a fantasy, to be sure, but they were rooted in the collective fears of a confused and dysphoric America, an America which had recently overcome Communism and lauded its rapidly developing technological sector as a new source of economic capital on the world stage. Y2K was scary because it played on a cultural fear of technology, which was paradoxically one of America’s key exports at the time.

It is an interesting contrast between the cultural environment of post-Cold War America and the loose backup calls of “brand new day,” with its rhythmic pleas to “stand up!” increasing in frequency and intensity as the song continues. Though the song has nothing to do with Y2K, or even technology, its position as a televised event after the ball dropped December 31, 1999, had solidified it forever in my imagination as a spiritual reaction to the technological paranoia of the time. Sting conveys a baptism narrative; as a country we had mysteriously been absolved of our technocratic sins. I was (and am) a believer. As I sit writing this on my iMac, I consider the many marketing strategies Apple has used in the last decade to convince me of the ways their software and hardware could define me as an individual. Sting redeems the pursuit of individuality through the use of gospel tropes. Instead of an almighty passing the judgement of heaven or hell, a technocratic neoliberal economy threatened the wrath of Y2K to nonbelievers at the turn of the millennium. As the proverbial gates to a new era of prosperity opened, Sting climbed higher in falsetto, “Stand up and be counted every boy and girl/Stand up all you lovers in the world/We’re starting up a brand new day.”

This year, as I watched a web steam of the ball drop January 31, 2010, I was able to later navigate to the MTV website and enjoy a Flaming Lips concert in Oklahoma City live from my computer. In this transition, something struck me. The potentials of computing, particularly video and sound editing (iMovie, Garageband and their disseminatory middle-man YouTube) still rely on an earlier Cold-War rhetoric of individualism and creative innovation to express the potential strengths of technology. Meanwhile any sense of collective ritual is set to the whim of a mouse-click, from New York to Oklahoma in a heartbeat. These new rituals compete with the old in a new context of hyper-individuality; ironically “Brand New Day” has become stuck once more in my head, as it has been routinely on New Years for the past 10 years. From these changes in collective ritual, what will it mean to celebrate the new year in 2011?

Bob Seger, Champion of Misfits

Bob Seger and the sort of classic rock he performs, embodies and represents, for me (and apparently many others), the relentlessly uncool. Youth, drugs and nonconformity have long been my standards of “rock,” and within this triad, Bob Seger’s formal, cinematic songs, have always come across as a little tired. Osvaldo Oyola wrote specifically last week about these foibles: the stilted piano and canned Chuck Berry riffs sound more like parody than gospel, while the parade of effects on Seger’s voice, also quite derivative, could have also fit on a Bruce Springsteen album (although you could replace the influence of Chuck Berry with that of the quintessentially less cool Phil Spector). Problematically, even though I loathe Seger’s catalog, I love Springsteen’s, this of course has made for some very popular conversations at the bar. In fact, it was last July at a local New Brunswick haunt that I had this conversation last. My friend, who will remain nameless, completely disagreed: Seger was cool, I just couldn’t hear it, in fact I had to see it to believe it.

Bob Seger and the sort of classic rock he performs, embodies and represents, for me (and apparently many others), the relentlessly uncool. Youth, drugs and nonconformity have long been my standards of “rock,” and within this triad, Bob Seger’s formal, cinematic songs, have always come across as a little tired. Osvaldo Oyola wrote specifically last week about these foibles: the stilted piano and canned Chuck Berry riffs sound more like parody than gospel, while the parade of effects on Seger’s voice, also quite derivative, could have also fit on a Bruce Springsteen album (although you could replace the influence of Chuck Berry with that of the quintessentially less cool Phil Spector). Problematically, even though I loathe Seger’s catalog, I love Springsteen’s, this of course has made for some very popular conversations at the bar. In fact, it was last July at a local New Brunswick haunt that I had this conversation last. My friend, who will remain nameless, completely disagreed: Seger was cool, I just couldn’t hear it, in fact I had to see it to believe it.

In order to understand Bob Seger, I needed to watch Mask, a 1985 retelling of The Elephant Man starring Eric Stoltz as the deformed Rocky Dennis and Cher as his mother Rusty Dennis. Mask was released two years after Risky Business, and featured a number of Bob Seger songs predominantly in the soundtrack. These songs uniformly mixed to the foreground, often serving as Rocky’s theme, juxtaposed against an ambient soundtrack of songs by black musicians like Little Richard and Gary US Bonds. These black oldies, “Tutti Frutti” and “Quarter to Three,” are used thematically when Rusty’s friends, a bunch of guys in a motorcycle gang, are partying. Not only is Rocky othered from the kids at school because he is ugly, he is poor, raised by a single mother with a drug addiction. Although whiteness takes center stage in this film, it holds a complex relationship to blackness. Rocky and Rusty are atypically white, finding community only with each other and a super-masculine network of bikers; they are misfits, doing their best to pass in a mainstream and affluent white society.

Bob Seger’s “Katmandu,” is the song which introduces Rocky in the opening credits. It is guilty of the trademark Bob Seger whiteness: more refurbished Chuck Berry and piano so droll it could have been played by a metronome. In the context of Rocky and his struggle to identify with white society however, it paints Seger in a different light. Bob Seger’s uncoolness can be read as a failed attempt to pay homage to black musicians like the aforementioned Little Richard and Gary US Bonds. Instead of suggesting a totalizing narrative of white appropriation, I argue that Bob Seger can be understood as a musician who would never be completely accepted by his heroes or critics. Reflected in the posters on Rocky’s wall and Universal’s contract negotiations with Columbia Records (Bruce Springsteen had been first choice for the soundtrack), Seger was not even cool to the director of the film, Peter Bogdanovich, who refered to his music as “inappropriate.”

Toward the end of the movie, Rocky holds his blind girlfriend for the last time. Her parents, disgusted by his face (but probably also by his shabby clothing), keep the two separate. Contradicting the escape narrative of Springsteen’s “Born to Run,” Rocky evinces the power of fantasy toward coping with discrimination: “We can’t run away Diana. But we can sort of run away in our minds. We can remember camp, the mountains and the Ocean…especially New Year’s Eve” (Mask Part 11 4:40). Like Rocky, Seger can’t run away from his whiteness, even though he may not relate to it, or fully embrace it, it is ever present in his recordings. Songs like “Old Time Rock and Roll,” “Katmandu,” and even “Night Moves” are celebrations of music as a forum of imagination – one where identity, be it black or white, can be reimagined as something else. Though “Old Time Rock and Roll,” will sound forever white, it relates the experience of otherness. Try as he might, Seger has no idea how to sound authentically black, and this is evident through both its celebratory lyrics and contrived arrangement.

Growing up in a bi-racial household, where, depending on the holiday, my Jewishness could be as visible as my blackness, I feel a strong kinship to figures like Rocky, not completely belonging to any ethnic community. Perhaps this led to a juvenile obsession with Springsteen, who, according to my father, everyone could relate to, regardless of color (he worked at an all-night Jersey Shore diner, the Inkwell, in the early 1970s). Bruce though, was never really misfit, mulatto or poor; whether discussing his working class freehold roots, or his first guitar, his music epitomizes white privilege. Even his stage shows feature Clarence Clemons, The Big (Black) Man, notably subordinate to Bruce, or “The Boss.” Although now, my Bruce phase seems laughable, I wonder if it was also a fantasy of fitting in, of recovering a fantastic and invisible whiteness deep within myself. When he wrote “Old Time Rock and Roll,” was Bob Seger trying to do the same and recover a font of blackness deep within himself? I now see a complex web of identity politics informed by an economic and social history of Rock and Roll, but this holds an uneasy and complex relationship with the part of me that still believes in rock and roll. I was, am, and forever will be the misfit who found an identity in the church of rock and roll. Though the sermons have changed, in high school, Springsteen was the pastor, and I suspect that for my friend at the bar, Seger also conducted service. Even though I could never completely fit in to the rich white world of these artists, I wonder if this speaks to a fundamental affinity. Did Springsteen and Seger ever feel like outcasts, later to find solace in the black cool of Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino? In the context of these figures and their music, how could whiteness seem anything but contrived, misfit and ugly – or in truth, is this dialectic really the beat which pushes rock and roll forward?

Growing up in a bi-racial household, where, depending on the holiday, my Jewishness could be as visible as my blackness, I feel a strong kinship to figures like Rocky, not completely belonging to any ethnic community. Perhaps this led to a juvenile obsession with Springsteen, who, according to my father, everyone could relate to, regardless of color (he worked at an all-night Jersey Shore diner, the Inkwell, in the early 1970s). Bruce though, was never really misfit, mulatto or poor; whether discussing his working class freehold roots, or his first guitar, his music epitomizes white privilege. Even his stage shows feature Clarence Clemons, The Big (Black) Man, notably subordinate to Bruce, or “The Boss.” Although now, my Bruce phase seems laughable, I wonder if it was also a fantasy of fitting in, of recovering a fantastic and invisible whiteness deep within myself. When he wrote “Old Time Rock and Roll,” was Bob Seger trying to do the same and recover a font of blackness deep within himself? I now see a complex web of identity politics informed by an economic and social history of Rock and Roll, but this holds an uneasy and complex relationship with the part of me that still believes in rock and roll. I was, am, and forever will be the misfit who found an identity in the church of rock and roll. Though the sermons have changed, in high school, Springsteen was the pastor, and I suspect that for my friend at the bar, Seger also conducted service. Even though I could never completely fit in to the rich white world of these artists, I wonder if this speaks to a fundamental affinity. Did Springsteen and Seger ever feel like outcasts, later to find solace in the black cool of Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino? In the context of these figures and their music, how could whiteness seem anything but contrived, misfit and ugly – or in truth, is this dialectic really the beat which pushes rock and roll forward?

AT

Recent Comments