“Let’s check in with Marabel May”: Audience Positioning, Nostalgia, and Format in Amanda Lund’s The Complete Woman? Podcast Series

In honor of International Podcast Day on 30 September, Sounding Out! brings you Pod-Tember (and Pod-Tober too, actually, now that we’re bi-weekly) a series of posts exploring different facets of the audio art of the podcast, which we have been putting into those earbuds since 2011. Enjoy! –JS

I’ve listened to an inordinate about of podcasts in the past year and half; the number of hours would be shocking. I’ve written about this previously: how audio, friendly voices in my ears, was a more comforting medium than television or film. In early 2021, Vulture’s Nicholas Quah published findings about the continuing rise of podcasts, suggesting that American audiences are intensifying their interest in the medium. He writes, “The case began to be made that podcasting, more so than many other new media infrastructures, was uniquely suited to meeting the moment,” suggesting that the pandemic has buoyed the medium extensively. His findings also show that podcast audiences are engaging more directly and are growing in diversity. The running joke about the medium is that everyone has a podcast. I certainly do. Comedians do. Talk show hosts do. Politicians do. In a recent episode of Bitch Sesh: A Real Housewives Breakdown Podcast, hosts Casey Wilson and Danielle Schneider joke that now every Real Housewife feels the need to start her own podcast, too.

In this 2021 moment, the series The Complete Woman? has become more relevant than ever, particularly in relation to the rise of conversations about the “Karen,” and a particular kind of white woman who attempts to wield social and racialized power. The podcast is marked as a “Baby Boomer” parody – or a fictional show directed at a fictional Baby Boomer audience. It’s eviscerating that culture, however, in its caricaturing of Marabel May and her friends, interrogating contemporary conversations about whiteness and middleclass-ness; its dark humor lies not in outdated gender roles, but in how incredibly close to home it all hits. It’s not a distant past, but a current reality.

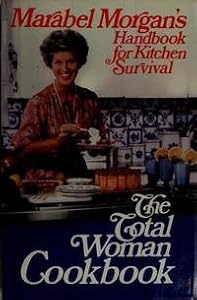

The Complete Woman podcast directly destabilizes nostalgia, even as it draws on older audio formats. In the series, comedian Amanda Lund parodies real-life mid 20th-century marriage self-help author Marabel Morgan, who promoted women’s deference to their husbands through evangelical Christianity – her book is titled The Total Woman, as mentioned by Vulture writer Nathan Rabin, a critical enthusiast of Lund’s series. The fictional Marabel May (voiced by Lund) is a housewife living in 1960s America with her husband, Freck (Matt Gourley). The Complete Woman series is set up as audio companions – diegetically understood as vinyl records – to Marabel’s book of the same name, which she penned after successfully saving her “disaster” of a marriage. She claims, “I believe it’s possible for any woman to manipulate her husband into adoring her in matter of weeks.” Each episode of the series focuses on a different aspect of womanhood or features a “checking-in” with Marabel and her “neighborhood gal” friends, aggressive Joanie (Maria Blasucci), muddled Barbara (Stephanie Allynne), and jovial divorcee Rita (Angela Trimbur).

The segments featuring Marabel chatting with her neighborhood girlfriends are particularly insightful, as each woman expresses her own warped version of the mid-century American marriage. They also combine the outdated instructional segments with more modern casual conversations, highlighting The Complete Woman’s addressing of women’s emotional labor, as well conventional housework. These segments also illuminate the distinctly female-driven nature of the series, as these voice actresses tend to improvise the discussions at hand. The back-and-forth between these women is both satirical and demonstrative of a sense of fun in their parody, and, at times, sincere friendship behind-the-scenes. Though a harsh satire of women’s positions in American culture, the show reveals a sense of community as Lund features her friends, all working comedians and actresses based in Los Angeles who find creative outlets in podcasting.

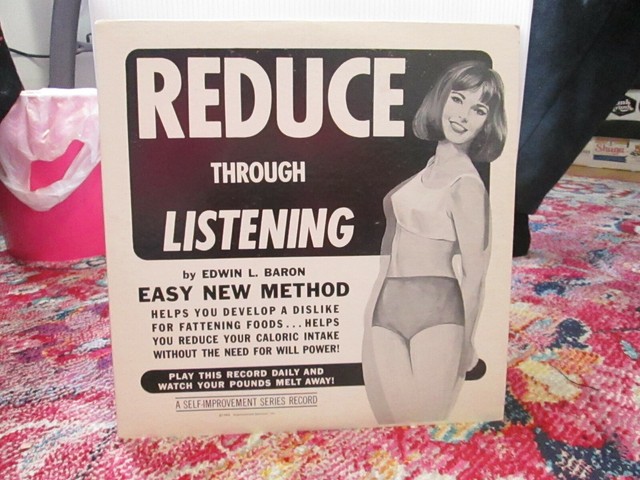

Format here, is significant too. The podcast directly satirizes an older format–self-help vinyl records–and its usage – questioning the ideologies of the past and present. The series conceptual set-up is nostalgic, but the content is not. The Complete Woman is unique in its use of format to draw on nostalgia for these pedantic vinyl recordings; the specificity of the audio and structure of the series suggests Lund has some fondness for these bygone formats. But the formatting is also used to critique and comment on the historical sexism and patriarchalism of marriage. While this is done with humor, the satire presented by the series sounds shockingly grounded in reality.

To understand the concept of The Complete Woman series, let’s examine the opening episode’s introductory narration. The first episode begins with the show’s recurring “groovy” 60s-style music, signaling a move to the past. While the show is about women for women, a male narrator is the first voice heard – an immediate indicator of Marabel May’s deference to men, and thus the imaginary audience’s, as well. The narrator states, “Welcome to The Complete Woman, the audio-companion to the number one bestselling book of the same name, written by Marabel May. It’s 1963, divorce is on the rise, the tides are changing, and marriages are drowning.”

The voices in the podcast sound echo-y and distant, reminiscent of listening to an old recording, which positions the listener as a participant – as if they are indeed in a struggle marriage and choosing to play this record and get advice from the fictional expert. Marabel then, in a deadpan manner, states, “Hi, I’m Marabel May, bestselling author, unaccredited marriage expert, and stay-at-home wife. Are you stuck in an unhappy marriage? Feel like there’s no hope in sight? You’re not alone. I receive millions of letters in the mail every day from sad people just like you. Here’s what they have to say.” Melancholic piano music starts playing as different voices – both male and female – express their unhappiness in their marriages: for example, “I mean how many nighttime headaches can one woman get?” Marabel comes back, after the sound of a record scratch, “But wait, there’s hope!” Again, the recording aspect pulls the audience into the fictional space of Marabel May and her dire need to save marriages.

The 60s-style music picks back up as the male narrator begins again, “Marabel May’s Complete Woman course is scientifically proven to improve your marriage – or your husband’s money back!” Marabel states, “But don’t take it from the faceless announcer guy. Take it from the countless, faceless, voices I’ve helped.” More voices of men and women are heard praising Marabel’s method: for example, “I used to get upset when dinner wasn’t on the table when I got home from work. Now, I know I’m right.” Marabel responds to these:

Thank you. Are you ready to take the next step toward marital bliss? You’ve read my bestselling book, now it’s time to jump into the audio companion. I suggest you listen to this record in a calm, quiet setting. Lock your children in their rooms and put your pets in a basket. Pour yourself an afternoon swizzle and settle in. You’re about to impart [sic] on a life-changing journey. Your husbands will thank you!

This exchange suggests both that the audience is enveloped into the diegesis of the podcast, but also the series’ dedication to a bygone format – though the dialog is humorous, the concept of The Complete Woman as a vinyl audio-companion never wavers.

The Complete Woman purposefully – and at times very uncomfortably – puts the listener in the position of someone who is genuinely interested in Marabel and her friends’ worldviews, who aligns with her outdated sexist and racist ideas: Marabel refers to “Oriental China,” and Barbara refers to “not being in Calcutta” when oral sex comes up in conversation. While lampooning these behaviors, the podcast is also forcing its listeners to reckon with them, to consider their own thinking as they are positioned as an audience who would agree with everything Marabel is saying.

What is additionally powerful about The Complete Woman is its reliance on authenticity in its sound. The doctrinaire voices of both the male announcer and Marabel May are so identifiable as typical affected self-help narration; their voices are upbeat but never hurry or seem too excitable – they maintain an evenness that is uncanny. Their tone and manners of speech undermine what the characters are actually saying, making this fictionalized companion album seem all the more legitimate, as if this series was found in a used record store – a kitschy yet forgotten audio self-help guide from the 60s. The intonation of the voices is overtly making fun of white voices assuming and exerting authority, no matter the absurdities that being spoken. The medium allows the audience to move in and out of positions: as genuine followers of Marabel May, as listeners of what might be a kitschy thrift store find, and as comedy fans. The sound maneuvers the audience constantly, suturing them to the aural space of the podcast in a myriad of ways.

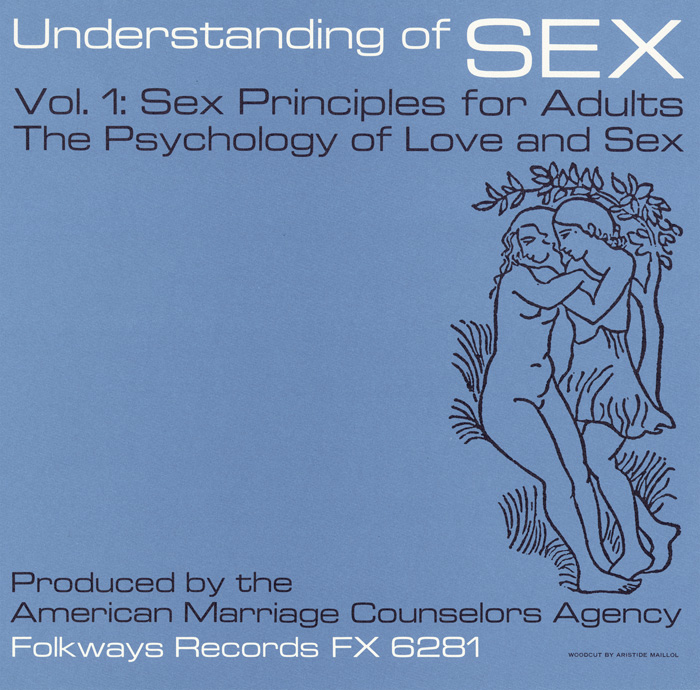

The Complete Woman parodies albums like Folkways Records produced in the mid-twentieth century, not just in its material, but also the length of the podcast episodes – a little over twenty minutes, just enough to fit perfectly on a vinyl side. The 1963 Folkways produced Understanding of Sex is a symptomatic example of precisely what the podcast is trying to mock, a pedantic authoritative voice, with liner notes boasting backing by doctors. Important, too, is the Folkways record’s completely white, heteronormative take on sex – which is here discussed solely in the context of maintaining a happy marriage. The Complete Woman’s devotion to the medium is humorous, but also in how it brandishes its critique of modern womanhood: its commitment to authenticity betrays how much Marabel’s teachings disturbingly relate to the modern moment.

The original The Complete Woman was followed up by four more series including the most recent, The Complete Christmas. I, however, want to dissect an example of scenes from The Complete Wedding’s second episode “Bridal Colors” in order to demonstrate how the series utilizes the podcasting format to position the audience as both in and out of the joke.

This episode uses sound to highlights the absurdist, yet bitingly relevant, commentary on wedding planning, both then and now. “Bridal Colors,” with women’s discussion of picking the perfect dress and color scheme for their weddings, especially underlines not only the parody of mid-century culture, but contemporary obsession with wedding planning. With the internet and influencer culture as an endless source of consumption, advice, and color palettes, modern wedding planning does not seem so different from Marabel’s suggestions – particularly in how both exude whiteness, middleclass-ness, and heteronormativity. Those resonances suggest that, despite The Complete Woman parodying a mid-century mindset and the use of older sound technologies, the analog and the digital are applied in very similar ways to maintain a status quo.

After giving the audience a quick quiz to help them figure out their “seasonal” colors, Marabel gives some specific suggestions for planning the perfect wedding. It is important to quote her entire speech on wedding scenarios in its entirety to fully understand how the series uses voice in concert with content to create its cutting yet absurd nature. Marabel speaks, as she always does, in a clear, enthusiastic, pedantic, very raced and gendered voice:

It’s science! – but for ladies. I’ll walk you through a few likely scenarios. I suggest taking notes with a pencil and paper. If you don’t have access to pencils or paper, chocolate syrup on a large cutting board is your best bet. If you’re a Winter having a city hall wedding, try a tea-length going away dress or a handsome woolen ensemble in French white with a veil-less headdress. Your flowers may be carried as a sheath or as an old-fashioned nosegay, pinned to a prayer book. Muffs are encouraged but not required. If worn, they must be flame-retarded [sic] or pre-burned. If you’re a Spring having a formal church wedding, try a long-trained brocade dress in true white and carry an impressive bouquet of American beauty roses, along with an ivory rosary. Jewelry may be delicate and preferably real. No feathers! – unless of course it’s a live canary, pinned to a broach borrowed by your mother-in-law’s estranged secretary. If you’re a Summer having a semi-formal wedding at home, try an ankle-length silk organza garden dress in bridal blush. Shoes are optional, but if worn must be made of glass blown by your tallest male relative on your maternal side. Sarah Bernhardt peonies are appropriate but no more than a half-dozen lest you come off looking braggadocio… is a word I learned!

Marabel’s voice is very candid, and she speaks quickly, as if this ridiculous list of arbitrary rules is a reminder for the audience of concepts of which they’re already aware. This monologue is exemplary of the series’ style – twisting banal aspects of material culture into absurdity to highlight the pressures put on women to perform and perfect things like weddings, marriage, and motherhood. “It’s science! – but for ladies” focuses on this fictional ideal that there is a formula that can lead to the perfect marriage, or that any aspect of idealized womanhood can be perfected if you just follow these easy steps. Woman’s work is implied here to be banal, because it is something expected, and if one fails, the consequences are dire.

While listening to Marabel go on is wildly absurd, it is also mocking a one-size-fits all mentality about weddings, and womanhood in general. The wedding comes to represent a particularly coded – white, middleclass, heteronormative – aspirational cultural practice that, in this midcentury moment of Marabel, is becoming solidified as something one is “supposed to do” and supposed to do in a certain way. It suggests to the audience, too, that these practices, while shifting, haven’t completely gone away. There are still expectations, traditions, and rituals that are widely expected to be performed by woman, relating not just to marriage, but work, sex, motherhood – the list goes on. This midcentury moment is still strongly felt in the contemporary moment, so as Marabel rattles off a list of what seem like insane rules – “Shoes are optional, but if worn must be made of glass blown by your tallest male relative on your maternal side” – they aren’t all that far off from today. These notions of perfected womanhood, too, are strongly structured by ideals held over from that time about race, class, and gender.

In “Bridal Colors,” the ladies of The Complete Woman also sit down to reminisce about their wedding themes – though Marabel is initially keen on having the ladies recall their roles in her own special day. When Marabel uncouthly mentions how much salve she used to clear up the many bug bites she received at Barbara’s backyard wedding, Rita sunnily jumps in with, “You know a little trick is you put toothpaste on ‘em.” Marabel, comically deadpan, replies (you can hear the massive eyeroll just from her voice), “Oh, Rita.” Heard on the recording, the voice actresses all burst out laughing at what sounds like an improvised moment. The absurdity of their conversation is brought to a halt by an honest suggestion, and it is quickly incorporated into the scene.

Voices shaking with a bit of laughter are heard throughout the series, but this stands out as particularly noticeable. It highlights the improvised nature of some of these group scenes by audibly breaking both the ‘60s narrative and the aesthetics of many contemporary hyper-edited studio podcasts. It would not be unheard in either moment to cut out the laughter or re-record the scene, but it is kept in, obvious to the audience. This laughter breaks the authenticity to the medium and works to successfully suture the podcast space to that of contemporary listeners. There is no frame to restrict, not only what can be heard, but what can be said. The diegesis spills into the space of the audience – they, too, are in the joke, for a moment no longer positioned as the fictional audience of Marabel May, but a comedy podcast audience. This builds a sense of community between listener and creator, as seemingly intimate moments of gaffes become integral to the both the diegesis of the podcast, but also the listening experience. In the case of The Complete Woman the format welcomes mistakes and improvisation as voices break out of characterization to comment on the reality behind the format – which is itself an important part of podcasting.

The comedy of The Complete Woman series is dark at times, as Lund notes both the limitations of women’s roles throughout the 20th century and highlights the ways in which things have not changed. While The Complete Woman is not directly calling on its audience to act, it is addressing the complexities of nostalgia for a previous moment by noting how, in some ways, it closely resembles the contemporary one. There is nostalgia found in the audio-companion concept of the series, but the content – while humorous – can be quite deep and painful. The Complete Woman does not succeed because it draws fondly on former sound technologies, but rather because it – often harshly – points out the pitfalls of nostalgia; Marabel May’s twisted world of the idealized straight white 1960s middle class housewife is often a direct commentary on the current position of women. The show suggests both that this kind of thinking hasn’t shifted much, but also, and more significantly in this moment, the conversation surrounding middle class white women’s complicity in upholding systemic racism. While the original The Complete Woman was released years before these conversations became widely prevalent, it holds up a satirical, yet bitingly revelatory mirror to the contemporary moment.

The podcast also amplifies the voices of the community of women behind it, who are looking critically at this moment in history by reframing and reengaging. It is worth noting Lund is a cofounder of the women-run Earios podcast network, that “strives to elevate the podcasting market with intelligent, diverse, subversive content BY WOMEN, FOR EVERYONE.” It is through comedy – ironically and inaccurately territorialized as a very “masculine domain” in the U.S. entertainment industry – and the genuineness of these scenes which break open the diegetic sound space of the podcast, that the audience can hear – and connect to – the very real women behind-the-scenes of the parody. Ultimately, through looking at series like The Complete Woman, it becomes clear that podcasting is more than a return to familiar formats (radio) – it is creating something new. Improvisation and comedy are particularly significant: the moments of improv and mistakes can create genuine connection.

—

Megan Fariello is a Chicago-based writer with a background in cultural studies. She is currently a contributor with Cine-File, and has recently published work in Film Cred and Dismantle. Megan is also a PhD graduate from the Cultural Studies program at George Mason University. This article draws and expands on work from her dissertation, titled The Techno-Historical Acoustic: The Reappearance of Older Sound Technologies in the Contemporary Media Landscape, which intervenes in the disciplines of cinema and media studies and sound studies, examining how the rise of aurally-focused narratives in contemporary media – including television and podcasting – are recasting processes of nostalgia.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies–Christine Ehrick

Gendered Voices and Social Harmony–Robin James

A Manifesto, or Sounding Out!’s 51st Podcast!!! – Aaron Trammell

This Is How You Listen: Reading Critically Junot Diaz’s Audiobook-Liana Silva

Surf, Sun, and Smog: Audio-Visual Imagery + Performance in Mexico City’s Neo-Surf Music Scene

Riding the Surf Wave in a City Without a Seashore

On April 24, 2005, at Zócalo square in downtown Mexico City, the Surf y Arena music festival gathered around 100,000 people and nine bands, ranging from local, barely known groups to big names in the new-wave surf music scene: Fenómeno Fuzz, Los Magníficos, Perversos Cetáceos, Espectroplasma, Los Elásticos, Yucatán A Go-Go, Sr. Bikini, Lost Acapulco, and Los Straitjackets, the latter being the only U.S. band in the festival. One year before, hardly more than a thousand people attended the event, organized in a smaller venue at Alameda del Sur, a few hundred yards south of Zócalo square. Perhaps not even the bands were prepared for the huge response in 2005. Interviewed by local newspaper La Jornada, Fenómeno Fuzz lead guitarist stated, “It’s the first time we see something like this, with so many people. Surf is an instrumental rock genre that was played in the 50s and 60s. There is no sand or sun here as in Acapulco, but we’ve brought downtown a bit of the beach vibe. In Mexico City there must be some 40 bands playing to this rhythm.” In the same interview piece, Lost Acapulco lead guitarist El Reverendo considered, “this festival is a success, for you realize this music is going up. People are on the same pitch. This is not a movement, but a style with many followers. […] It doesn’t matter if there is no beach here—you have to imagine it.”

Sr. Bikini at Rock and Road on 30 de Marzo 2013, Image by Flickr User José Miguel Rosas (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The bands who played at the 2005 Surf y Arena Festival wondered whether the success was transitory or would endure. More than a decade later, some are still active, most notably Lost Acapulco, whose singles and compilations have been released in countries like Spain, Italy, and Japan; they have toured around the world, and have released a new EP, Coral Riffs (2015). Los Straitjackets lead guitarist Danny Amis has collaborated with local surf bands like Lost Acapulco and Twin Tones; after surviving a hard battle against cancer, he moved to Mexico City’s Chinatown. Los Elásticos also released a new album, Death Calavera 2.2, the Espectroplasma members formed Twin Tones and have played, toured and participated in the short film inspired by their first record, Nación Apache. In 2016, the Wild’O Fest brought together old and new surf stars, starring The Fleshtones (U.S.) and Wau y los Arrrghs! (Spain), as well as local legends Los Esquizitos and Lost Acapulco. In February 2017, the Russian band Messer Chups toured across Mexico, playing with local bands in several cities. So it seems the scene is alive and kicking.

Lost Acapulco’s LP Acapulco Golden cover art by Dr. Alderete (2004). Masks became a famous trait of Mexican surf music. Danny Amys from Los Straitjackets and some Lost Acapulco members wear them on stage, as well as many other surf bands. This cover echoes films from the 50s and 60s featuring wrestlers like Santo and Blue Demon.

Today we can listen to how surf music shaped part of Mexico City’s underground music scene in the last decade of the 20th century and the early 21st. Being 235 miles away from Acapulco, one might wonder how wearing sandals, short pants, floral print shirts, plastic flower necklaces, and dark sunglasses became trendy in the country’s capital city. To this beach imagery, surf bands and fans added references to classic Mexican media icons, like wrestler Santo, comedian Mauricio Garcés, and black and white sci-fi movies. The work by visual artists like Dr. Alderete—who has designed covers and posters for many surf bands, such as Lost Acapulco, Fenómeno Fuzz, Telekrimen, The Cavernarios, Los Corona, among others—has been crucial for this imagery cross-reference process.

Lima-based visual art magazine Carboncito cover art by Dr. Alderete (2012). The cover features Kalimán, main character of an old Mexican comic strip, as well as other characters associated both with surf imagery (the Rapa Nui statue, oddly resembling a bamboo Tiki figure) and spy films like James Bond.

In this article I portray the neo-surf music scene in Mexico as a cultural-musical set of audiovisual and performative traits shared, modified, and transmitted by the scene’s partakers. It cannot be said there is a surf music “urban tribe” (a trendy concept for several years in Mexican youth studies), but rather shared “aesthetic” expressions of cultural syncretism, responding to the increase of atomization and alienation in Mexico City.

Just as in ska, punk, or hardcore rock, a number of surf concert attendees participate in typical genre-related rituals like moshing. Surf fans, however, are more “performatic” in the way Diana Taylor understands this term in The Archive and the Repertoire as “the adjectival form of the nondiscursive realm of performance” (6). Several surf concert goers wear masks, originally worn by notorious Mexican wrestlers like Santo, Blue Demon, and Rey Misterio (whose son would later become a WWE star). At the concert, when a song’s tempo suddenly stops or changes, masked dancers pose as if weightlifting, jump and crowd surf, stage fights, and mimic swimming movements. Surf music is the lyric-less soundtrack for the intertwined performance of different cultural traits, portraying a prolific tension between a hedonistic attitude associated with an invented nostalgia for West Coast surf culture, and the halo of exoticness surrounding Mexican culture in the U.S. imaginary, as portrayed by surf bands and artists (just to name a few, Herb Albert’s “Tijuana Taxi,” Link Wray’s “Tijuana,” and Los Straitjackets’ “Tijuana Boots”).

Mosh pit with masked participants. On stage, Lost Acapulco plays “Frenesick.” Multiforo Alicia, Mexico City, March 20 2009.

Tracing the Origins of Mexican Neo-Surf Music Scene

1960s Mexican rock and garage bands do not usually have instrumental songs in their repertoire, as is the case with Los Sleepers, or Los Rockin’ Devils. However, there are some examples of incursions in surf-related instrumentals, such as Los Teen Tops’ “Rock del diablo rojo,” or Los Locos del Ritmo’s  “Morelia.” It was not until Toño Quirazco (1935-2008) formed Quirazco y sus Hawaian Boys, though, that we find a Mexican instrumental song, “Surf hawaiiano,” explicitly using the noun “surf” as an identity marker, just like “Traveling Riverside Blues,” or “Jailhouse Rock”. The use of a pedal steel guitar (portrayed in their 1965 eponymous album cover photo), and its association to Hawaiian music through the slide guitar method, makes exotism an early sonic feature of Mexican surf. Born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Quirazco was not as famous as Los Teen Tops or Los Locos del Ritmo, but he is a key forerunner not only of surf music, as he is also known for having introduced ska to Mexican audiences, with songs like “Jamaica Ska” and “Ska hawaiano,” both off his album Jamaica Ska, also from 1965.

“Morelia.” It was not until Toño Quirazco (1935-2008) formed Quirazco y sus Hawaian Boys, though, that we find a Mexican instrumental song, “Surf hawaiiano,” explicitly using the noun “surf” as an identity marker, just like “Traveling Riverside Blues,” or “Jailhouse Rock”. The use of a pedal steel guitar (portrayed in their 1965 eponymous album cover photo), and its association to Hawaiian music through the slide guitar method, makes exotism an early sonic feature of Mexican surf. Born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Quirazco was not as famous as Los Teen Tops or Los Locos del Ritmo, but he is a key forerunner not only of surf music, as he is also known for having introduced ska to Mexican audiences, with songs like “Jamaica Ska” and “Ska hawaiano,” both off his album Jamaica Ska, also from 1965.

Although surf music bands suffered heavily with the arrival of the British Wave, not all of them disappeared. Bands such as The Ventures became famous for covering surf standards. Others, like The Beach Boys, eventually migrated to different music styles. Later in the 1970s and 80s, bands like The Cramps, The Stray Cats, and The Go-Go’s kept alive surf-related styles, so that by the time Pulp Fiction appeared, in 1994, there were some interesting bands we already can consider “neo-surf,” such as Man Or Astroman? and The Tantra Monsters; Los Straitjackets re-formed and Dick Dale began touring again. Quentin Tarantino’s soundtrack to Pulp Fiction (including songs by Southern California surf rockers Dale, The Tornadoes, The Revels, The Centurians, and The Lively Ones) contributed to bringing surf music back to mainstream attention, now as a vintage sound commodity (Norandi, 2002).

We might call this “the Pulp Fiction effect,” a phenomenon recognized by stakeholders in the scene, like Los Esquizitos guitar and theremin player Güili:

One day Nacho came up with the idea that we should play surf, because it was the moment in which […] in Satélite [a northern Mexico City neighborhood ] all bands wanted to play funk like Red Hot Chili Peppers or Primus. It became a virtuoso slap competition, and precisely no one was playing surf […]. Shortly afterwards, Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction was released and surf exploded impressively with the movie’s theme. But we were already riding the surf wave.

Multiforo Alicia has been an important venue for the consolidation not only of a surf scene, but also of other emerging movements at the time. Founder and owner Ignacio Pineda remembers,

When we started Multiforo Alicia [in 1995], there was a generational shift. There were a lot of new bands that didn’t fit into what had been going on in the last 10 or 11 years, and they were the punk rock, ska, hip-hop, transmetal, emo, and nu metal movements, which nowadays are quite normal. […] Luckily for us, [Alicia] was like home for all of them.

Interview with Multiforo Alicia owner Ignacio Pineda, 2011

It is a common venue for surf bands (Norandi, 2002, Caballero, 2012), and through their recording label, Grabaxiones Alicia, they have produced albums for some of the most interesting instrumental rock projects in Mexico, among them Twin Tones/Espectroplasma/Sonido Gallo Negro (three groundbreaking bands with the same members), Los Esquizitos, Los Magníficos, Telekrimen, The Cavernarios, and Austin TV. Massive festivals and concerts, like Vive Latino or Surf y Arena, have also contributed to positioning neo-surf as an ongoing trend in alternative rock.

Masking Identity, Performing Difference

While the emergence of Mexican neo-surf was contingent upon local and international music trends in the mid-90s, its permanence has been due to processes of cultural syncretism and appropriation. Wrestler masks are a good example. Worn first by Danny Amis, and later on by Los Esquizitos and Lost Acapulco, masks quickly spread out as a neo-surf visual icon. Los Esquizitos drum player, Brisa, doesn’t remember there being an aesthetic justification behind the masked man using a chainsaw portrayed in their first album cover. Nacho complains, “Argh! We created a monster unawares! Ah, I sometimes regret that. I really regret having worn masks at a concert.”

Los Esquizitos greatly contributed to blend a Mexican surf flavor through their imagery on stage, as well as with their most emblematic song, “Santo y Lunave.” One of the few songs with lyrics in the scene (and with spoken word rather than singing), it tells story of how Santo got lost in space, turning him into an important figure of Mexican neo-surf imagery. As Güili recognizes, “I think it was after the ‘Santo’ song when all the Tetris pieces fit perfectly into place—wrestling, masks, floral print shirts, surf— everything in the same box.”

Live version of “Santo y Lunave” by Los Esquizitos, Vive Latino Music Festival, Mexico City, May 17, 2009. The song was originally released in their first LP (1998)

“Performatic” moshing is another example of cultural appropriation. The apparently random movements of moshers in heavy metal concerts have been compared to the kinetics of gaseous particles (as in Silverberg, Bierbaum, Sethna & Cohen’s “Collective Motion of Moshers”) but in surf concerts their movements cannot be reduced to the categories of “self-propulsion,” “flocking” and “collision.” Here moshers interact in more complex ways, mimicking wrestling movements to the rhythm of the song in turn, enacting fights between masked and unmasked opponents, and helping other moshers to jump over the audience and crowd surf. They consciously perform the icons they associate with surf culture. They are aware of the differential traits existing between this and other rock sub-genres, and they externalize them through ritualized behaviors. In other words, Mexican surf concert goers adopt moshing to participate in simulacra about stereotyped representations of Mexican culture and subjects.

Dancing Desires

In his book Popular Music: The Key Concepts (2nd ed), Roy Shuker describes surf as “Californian good time music, with references to sun, sand and (obliquely) sex” (2005, 262). This sexual suggestiveness is still present in Mexican neo-surf, as can be noticed in songs like Fenómeno Fuzz’s “El bikini de la chica popof” [“The Snob Girl’s Bikini”]:

Ella viene caminando en su bikini de color,

ella viene caminando y a todos nos da calor,

y sus piernas bien bronceadas me hacen suspirar.

Ella viene caminando y no ve a nadie más.

[She’s walking by, wearing her colorful bikini,

she’s walking by and everyone gets hot,

and her well-tanned legs make me sigh.

She’s walking by and doesn’t look at anyone else]

Other bands seem to reinforce this fetishization. Sr. Bikini have sometimes hired women dancers wearing masks and bikinis for their shows, and Los Elásticos have a permanent member, La Chica Elástica, who dances in every live show.

[Final part of a Los Elásticos concert in 2012, featuring La Chica Elástica. All-men and all-women mosh pits can be seen at 0:40 and 3:36.]

However, even though sometimes subject to hedonistic and stereotyped representations, women participate in every level of the scene, expressing agency as band members, scenemakers, and/or fans. Women play in the most representative bands, such as Fenómeno Fuzz’s former singer and bass player, Biani, or Los Esquizitos drummer, Brisa. There are also all-woman bands, such as Las Agresivas Hawaianas (whose brief existence is scarely documented on the internet), rockabilly trio Los Leopardos, and garage-oriented Ultrasónicas, whose members have continued playing solo, most notably Jessy Bulbo.

Offstage, both genders wear masks and enter the pit. Sometimes, when there are many moshers, men and women gather in separate pits. Dancing is much more prominent in the surf scene than in punk; participants appropriate a go-go, swing, rock ‘n’ roll, and ska dancing moves, mixing them with wrestling and weightlifting positions. The attendees accomplish their middle-class expectations of leisure and entertainment by showing off their outfits, feeling desire, desired and/or admired (even if ironically) through dancing and moshing—literally by performing such expectations in situ.

The scene overall, has been critiqued for being too retro and insulated from political critique. As La Jornada‘s Mariela Norandi points out, “an element that the Mexican movement has inherited from the origins of surf is the lack of ideology. Curiously, surf is reborn in Mexico in a moment of political and social unrest [in the mid-90s], with the Zapatista uprising, the peso devaluation, Colosio’s murder, and Salinas’ escape” (2002, 6a). The fact that this scene has survived for over two decades, despite the many economic and political crises Mexico has faced ever since, suggests it works as an ideological outlet for scene partakers to elude their social reality. Just as it happened in the 60s with the Vietnam War, once again surfers stay away from social and political problems, and reclaim their right to have fun and dance. They wear their floral print shirts and dance a go-go style, remembering those wonderful 60s (6a). For Norandi, the lack of lyrics in surf music may be partly responsible for most surf bands seemingly uncritical position.

Into the Surf Sound

Although half of Mexico’s states have a seashore, surf music in the capital is related to everything but actual surfing. The imagery built around it, considered “surrealistic” by Norandi (6a), is the most visible novelty in the new scene, since melodically and rhythmically speaking surf remains fairly simple, like garage or punk. However constrained, like other genres, to the 12-bar blues progression, it is in timbre where we appreciate how surf sound has been defined by several generations of music bands and players. A triple-level approach to surf music (timbral, melodic, and stylistic) can account for the creation and development of several genres or scenes associated to the rise of Mexican neo-surf, like chili western (Twin Tones, Los Twangers, The Sonoras), space surf (Espectroplasma, Telekrimen, Megatones), garage (Ultrasónicas, Las Pipas de la Paz) and rockabilly (Los Gatos, Eddie y Los Grasosos, Los Leopardos, among many others).

Appropriation, practiced through covering standards and imitating riffs and melodies, has been always crucial for shaping the surf sound, just as it was in preceding genres that influenced rock ‘n’ roll, like blues, twist, and jazz. Although not exactly referred to as “surf standards,” there are some foundational songs that shaped the surf sound. Three pieces nowadays still debated as the first surf song—Duane Eddy’s “Rebel Rouser,”Link Wray’s “Slinky,” and Dick Dale’s “Miserlou”—influenced not only contemporary bands and their immediate successors, but also musicians in the ’90s wave.

These and other composers contributed collectively to establishing surf music’s standard traits: the 4/4 drum beat (whose earliest template may be Dale’s “Surf Beat”), the “wavy guitar” riff (perfectly illustrated in the beginning of The Chantay’s “Pipeline”), an extensive use of reverb, and the appropriation of “exotic” tunes (such as the Lebanese melody that inspired Dale’s tremolo style in “Miserlou”). Many surf songs contain, in particular, traits from “Slinky’s” guitar and “Surf Beat’s” drums. Both are simple and repetitive, but can be combined with other arrangements at will. This formula has been used in countless surf songs ever since.

Covering is a way of making connections with specific songs, and paying homage to (or deflating) admired bands and musicians. Links between a band and certain collaboration networks are thus established. Sr. Bikini covered Alpert’s instrumental version of The Beatles’ “A Taste of Honey,” setting up a dialogue with a musician that played a lot with Mexican stereotyped imagery and sounds (like the trumpets, substituted by electric guitars in Sr. Bikini’s version).

Covering is a way of making connections with specific songs, and paying homage to (or deflating) admired bands and musicians. Links between a band and certain collaboration networks are thus established. Sr. Bikini covered Alpert’s instrumental version of The Beatles’ “A Taste of Honey,” setting up a dialogue with a musician that played a lot with Mexican stereotyped imagery and sounds (like the trumpets, substituted by electric guitars in Sr. Bikini’s version).

Lost Acapulco renamed The Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird” as “Surfin’ Band,” participating in a long chain of covers (including The Cramps and The Ramones) of a song that in turn was the result of mixing two pieces by The Rivingtons, “Bird’s The Word” and “Papa Oom Mow Mow.” Los Esquizitos have their own covers of The Cramps’ “Human Fly” (“El moscardón”) and Rory Erickson’s “I Walked With A Zombie.”

Los Magníficos’ “Píntalo de negro,” after The Rolling Stone’s “Paint It Black,” shows that, just as in punk, any piece can be turned into a surf song.

Sometimes it is just a trait (a riff, or a beat) that is referenced. Fenómeno Fuzz’s initial riff in “Tiki Twist” resembles Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” whereas two chili western songs (“Transgenic Surfers” by Los Twangers and “Skawboy” by The Bich Boys) echo The Ramrods’ harmonic and timbral arrangements for “Riders In The Sky,” another song with a long cover history, including Dale, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley. A surf version of this song was familiar to Mexican TV viewers in the 90s, since it was a regular soundtrack of furniture store Hermanos Vázquez spots.

Surf was born at a time when stand-alone effects units were just about to change the way music was made, taking audio manipulation off the studio and bringing it to the stage. For example, The Shadows are known for having used the tape-based Watkins Copicat, “the first repeat-echo machine manufactured as one compact unit” according to Steve Russell, responsible for the guitar delay effect in their 1960 rendition of Jerry Lordan’s “Apache,” since then a surf standard. In his book Echo and Reverb, for example, Peter Doyle examines how effects like echo/delay and reverb shaped sonic spatiality in 20th century popular music recording in the U.S., from hillbilly, country, blues, and jazz to rock ‘n’ roll.

Although Doyle only dedicates a few paragraphs to Dale, Wray, and surf instrumentals, acoustic effects greatly contributed to characterize their styles as well. Some traits are intricately related to genre specific manifestations, like the double bass in rockabilly, or the twang effect in chili western. Timbre, then, is the aural counterpart to the scene’s visual aspect, “invoking the rich semiotic traditions that wove through southern and West Coast popular music recording” (Doyle, 2005, 226). It has become a way both to continually define the genre and, in the Mexical neo-surf scene in particular, to overcome melodic and harmonic limitations. Thanks to timbral play, what used to be a blind alley in rock history became in the 1990s a mirror for young generations of Mexicanos to create and feel aligned with fashionable trends, and a sonic filter enabling them to examine their social situations and, sometimes, to willfully sidestep them.

—

Featured Image: Lost Acapulco in Estadio Azteca 2009, Image by Flickr User Stephany Garcia (CC BY-ND 2.0).

—

Aurelio Meza (Mexico City, 1985) is a PhD student in Humanities at Concordia University, Montreal. Co-organizer of the PoéticaSonora research group at UNAM, Mexico City, where he is in charge of designing and developing a digital audio repository for sound art and poetry in Mexico since 1960. Author of the books of essays Shuffle: poesía sonora (2011) and Sobre Vivir Tijuana (2015). Blog: http://aureliomexa.wordpress.com/

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Recent Comments