“Playing the Medieval Lyric”: Remixing, Sampling and Remediating “Head Like a Hole” and “Call Me Maybe”

Each of the essays in this month’s “Medieval Sound” forum focuses on sound as it, according to Steve Goodman’s essay “The Ontology of Vibrational Force,” in The Sound Studies Reader, “comes to the rescue of thought rather than the inverse, forcing it to vibrate, loosening up its organized or petrified body (70). These investigations into medieval sound lend themselves to a variety of presentation methods loosening up the “petrified body” of academic presentation. Each essay challenges concepts of how to hear the Middle Ages and how the sounds of the Middle Ages continue to echo in our own soundscapes.

The posts in this series begins an ongoing conversation about medieval sound in Sounding Out!. Our opening gambit in April 2016, “Multimodality and Lyric Sound,” reframes how we consider the lyric from England to Spain, from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries, pushing ideas of openness, flexibility, and productive creativity. We will post several follow-ups throughout the rest of 2016 focusing on “Remediating Medieval Sound.” And, HEAR YE!, in April 2017, look for a second series on Aural Ecologies of noise! –Guest Editors Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

–

In 2013, a user named pomDeter posted a sound file on the social news and entertainment site Reddit that went viral in the form of YouTube videos, Facebook posts, and tweets: a mashup remediation of Nine Inch Nails’s “Head Like a Hole” with Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe.” Reactions ranged from outrage on the part of Nine Inch Nails’s drummer to declarations that it is a work of “genius” by the Los Angeles Times.

To understand the significance of this surprising piece of pop culture, we should recall that the iconic industrial rock anthem with sadomasochistic overtones “Head Like a Hole” is a track from NIN’s debut Pretty Hate Machine (1989), while “Call Me Maybe”–the title track to Jepsen’s eponymous first album—is a anthem about the exhilaration of a crush. Simply put, these two musical universes are not usually mentioned in the same breath, much less remixed into the same track. The result? “Call Me a Hole.”

The commentary about this musical clash of cultures has been vigorous and multi-sided. Listeners have unabashedly loved it, absolutely hated it, been very disturbed that they loved it, and been deeply distressed by what they see as the diluting of pure rock rage.

“Call Me a Hole” is a good example of both the theoretical underpinnings and the experimental possibilities of the issues at stake in my discussion of the medieval lyric. My post not only allows you to play the remix, but also to visualize the remixed song and read the second-by-second stream of commentary from a wide range of listeners. In this way, this remediated, multimodal, multimedia moment perfectly encapsulates the possibilities of experimentation, the participatory culture of multimodal productions, and the simultaneous discomfort and seduction these experimental remixings may engender. The commentary on Soundcloud is a perfect record of all these things: this cultural production is “awesome, creepy, bittersweet, disturbing, strange, brilliant, genius.”

“Playing the Medieval English Lyric” briefly examines the emergence of the lyric form in 13th-century miscellanies—an emergence that, in many ways, mirrors the development of mashups like “Call Me a Hole.” This work dovetails with larger critical issues apparent in deeply examining the material culture of miscellanies—medieval anthologies—how they were made, their quire formations, their marginalia, their scribes, their audiences. But I juxtapose this investigation with the insights of more recent theoretical ideas about multimodality, remediation, and mashup. Both recent digital rhetoric and medieval rhetorical theory can help us think through the place of music in the emergence of new literary genres and contextualize the creation of new technologies of sound.

Image by Richard Smith @Flickr CC BY.

The mashup as a new musical genre especially dependent on the affordances of a digital platform transforms the place of the audience from mere “consumer” to “producer,” according to Ragnhild Brøvig-Hanssen’s entry “Justin Bieber Featuring Slipknot: Consumption as Mode of Production,” in The Oxford Handbook of Music and Virtuality (268). Mashups also switch the relation of the producers/composers of music into the role of consumers/listeners. Brøvig-Hanssen goes on to argue that “it is often [mashup’s] experiential doubling of the music as simultaneously congruent (sonically, it sounds like a band performing together) and incongruent (it periodically subverts socially constructed conceptions of identities) that produces the richness in meaning and paradoxical effects of successful mashups (270).

These incongruent, yet congruent juxtapositions that produce rich meaning also form the pattern I see in the emergence of medieval English lyric. In essence, I hope to show how a discussion about digital mashups in today’s musical ecosystem can help us reframe the emergence of the medieval lyric in 13th-century medieval Britain. How do different media platforms—manuscript and digital—spur on certain parallel forms of sonic media play and creativity?

In particular, I am interested in how the sampling, mixing, and palimpsestic juxtaposition of mixed-language manuscripts (usually including Latin, Anglo-Norman French, and Middle English) have created a space for new linguistic and sonic remixes and new genres to play and form. In this article, I reconsider the (really) “old” media of the manuscript page as a recording and playing interface existing at a particularly dynamic juncture when new experimental forms abound for the emergence, revision, and recombination of literary oeuvres, genres, and technologies of sound.

Multilingualism and the Medieval English Lyric Scene

Image used for purposes of critique.

Just as a screen shot of the “Call Me a Hole” website would preserve in static form such external references as links to articles discussing the mashup (and would allow future readers to add new information), I similarly argue that a medieval manuscript page has creative, annotated possibilities that stop it from being a fixed, “literate” page. Readers throughout the centuries may add marginal notes, make annotations, cross out sections, or add new sections. More visually-oriented readers may include marginal drawings, even going so far as to animate narratives by drawing a series of connected images or to add interactive features like flaps, or rotae. If the manuscript page in question includes lyrics, notes, or both, it may have served as the inspiration for a wide variety of dramatic or musical performances, whether public or private. Finally, the physical book itself may have been broken apart, recombined with other books, or reused as endpapers for other books. In this way, I advocate for an understanding of the manuscript medium as a dynamic media zone like the digital screen. The manuscript page is thus, a mise-en-système: a dynamic reading/recording interface.

Much of the vernacular English literary production in the 13th and into the first half of the 14th century is preserved in multilingual manuscripts. I think Tim Machan said it best at 2008’s Multilingualism in the Middle Ages conference, particularly in situating Middle English in England, when he talks about “the ordinariness of multilingualism” and how much it is “the background noise” in the Middle Ages in Britain. The thirteenth-century multilingual matrix included verbal and written forms of the following languages: Old English, Middle English, Latin, Greek, Anglo-Norman French, Continental French, Irish, Welsh, Cornish, Hebrew, Flemish, and Arabic. If multilingualism is the background noise, then it’s a background concert in which all those linguistic sounds perform simultaneously. The medieval manuscript’s ocularcentrism has given readers visual cues, but the cues ask us to remix, reinterpret, and reinvent the materials. They do not ask us to just see these signs—whether music, art, text—as separate, hermetically sealed universes working as solo acts.

Intersecting this active ferment was the creative flux and reinvention of English musical notation and distinctly regional styles. These forces, I believe, helped create an experimental dynamism that may explain what the manuscript record reveals about the emergence of the Middle English lyric. The notation of Western music as we now understand it, which would begin to emerge in the 9th century, focused heavily on religious music, on chant. And Latin chant can be syllabically texted to any music. Likewise, Anglo-Norman French poetry focused on a form using syllable counts—octasyllabic couplets. This poetic form also was easily translated into Western musical notation. What, however, do you do with English poetry that is alliterative or uses another kind of stressed poetic meter? These problems are, in fact, probably why it took some time for Middle English to produce lyrics that were texted to music.

Image by Juanedc @Flickr CC BY.

Another reason for this phenomenon lies with the state of musical notation itself. In the entry on “musical notation” in the New Grove Dictionary of Music (http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/public/book/omo_gmo), an entire history of the creation of musical notation in the Middle Ages—and specifically its experimental and regional varieties—are mapped out. In addition, Carl Parrish’s classic text, The Notation of Medieval Music, a standard in all musical paleography classes, shows the minute shifts in the construction of medieval music from century to century and from region to region. And finally, the development of the stave line as “new technology” would spur further writing of music “without additional aural support.” What these histories of medieval musical notation have in common is their emphasis on the constantly shifting paradigms that this new technology of writing to record sound showed across different regions and different centuries.

From the second quarter of the 13th century to the mid-14th century, a number of multilingual miscellanies have survived, preserving an astonishing breadth of poetic work in Latin, Middle English, and Anglo-Norman French. These books circulated in relation to each other and in conversation with each other and were collected and compiled in miscellanies. There are a fair number of multilingual miscellanies that contain a range of lyrical poetry in Middle English and Anglo-Norman French. My list here is not exhaustive, but I would like to point to a few (pulled from Laing and Deeming’s work) that we will discuss: Oxford, Jesus College MS 29; Oxford, Bodleian library MS Digby 86; London, British Library MS Arundel 248; London, British Library MS Egerton 613; London, British Library MS Egerton 2253; London, British Library MS Harley 978; Kent, Maidstone Museum A. 13; Cambridge, St. John’s College MS E.8; London, British Library MS Royal 12 E.i; Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson G18.

With the exception of the criticism of Harley 978, the manuscript containing the famous “summer canon,” which only contains one piece of Middle English poetry, the scholarly discussion of the miscellanies’ lyrics rarely touches on music (with the notable exception of Helen Deeming’s assiduous work). This critical silence is particularly disconcerting because several of these manuscripts either have notes or signs of music in them, or their lyrical texts have music attached to them in other manuscripts. What I would like to propose, then, is a narrow sampling that will give us a wider picture of what the lyrical record may reveal.

Poetic and Musical Samplings of the Lyric Page

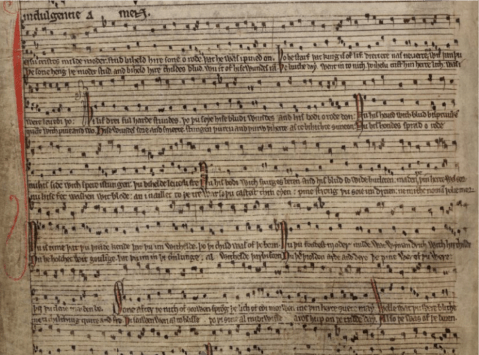

The manuscript layouts of a sample of these medieval multilingual musical miscellanies reveal how musical notes and letters were, at times, considered in the same category. The mise-en-système of these manuscripts also reveal the fluidity, creativity, and cues for audience/listener/reader’s (including the scribal compiler) ability to mashup the multilingual musical matrix. In the manuscript Arundel 248, music is attached to the lyrics, but it is laid out in quite an unusual way. Arundel 248 contains mostly Latin religious texts, including several tracts on sin. However, near the end, there are several lyrical texts that also appear in Digby 86; Jesus 29; and Rawlinson G. 18. On f. 154r, the entire page has Latin, Anglo-Norman, and English verse texted to music. What is interesting about this page, especially in comparison to other musical pages in the MS and the standard layout of thirteenth-century English music, is the folio’s mise-en-page. The scribe has literally laid out a series of lines (particularly in the top half) that then places English poetry, Anglo-Norman French poetry, and Latin poetry with English musical notation. The lack of specific stave lines (though they appear in other parts of this manuscript and at the bottom of this folio) means that the technology of this particular form of sound recording has allowed all these different things—English musical notes, English vernacular notation, Latin notation, and Anglo-Norman vernacular notation—equal space and play. They all have been squeezed onto these black ruled lines (at the top). The mise-en-page, then, allows linguistic differences to be on par with differences in sonic styles. What this manuscript ultimately creates is a miscellany of sound.

The page’s layout cues a sonic palimpsest—or, in contemporary terms, a sonic mash-up—and suggests potentially simultaneous performance. In fact, this vocal performance becomes even more complex in the next slide, f. 154v, because the texted English lyric is a polyphonic piece that also, in many of its manuscripts, has Latin lyrics. This is “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder,” (DIMEV 2831 http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=2831) which comes with English lyrics and texted music. It appears to be a version of “Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem,” though the standard version with music appears in St. John’s College, MS E.8 with the standard English lyrics underneath the melody (DIMEV 5030 http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=5030 ). The latter English lyric connected to “Stabat Iuxta” is “Stand wel moder” and there are several versions of the lyric without music—Digby 86, Harley 2253, Royal 8 F.ii, Trinity College, MS Dublin 301. Another manuscript, Royal MS 12 E.i, contains the same music for “Stand wel moder.” Deeming has noted that the lyrics of this version, “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” correspond closely to “Stabat Iuxta” and could be sung with the standard melody (as seen in Royal 8 F.ii) as a contrafactum. However, you can do a mashup of “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” and its accompanying music juxtaposed with the text and music of “Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem.” As an experiment, I had Camerata, the early Music Group at Vassar College, record this piece, “Jesu Cristes Milde Moder” from Arundel 248 with the musical version of “Stabat Iuxta” from St. John’s College MS E.8 (Found in Deeming’s Songs in British Sources (196, 201, 210-211). Other than direction on how to pronounce Middle English (as well as the accompanying contemporary editions of each lyric), I left the performance details to the group themselves to figure out. This is what they recorded – this is the medieval mashup.

The performance shows the creative possibilities of the page, and how music is a very distinct kind of sound player. What song—and particularly multi-part song—has done, is to generate sonic harmony out of linguistic babel. There is a pattern of circulation that intertwines music (both monophony and polyphony) with multilingual lyrics, and this manuscript especially demonstrates those sonic possibilities. These pages demonstrate a diverse soundscape that records and imagines an interesting multimedia and multilingual voice at play. In essence, Arundel 248 displays the different possibilities a reader could have in switching between or layering different modes of sound.

“Stabat Iuxta Christi Crucem.” London, British Library MS Arundel 248, f. 154v.

—

Featured image “staff” by Arko Sen @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND

—

Dorothy Kim is an Assistant Professor of English at Vassar College. She is a medievalist, digital humanist, and feminist. She has been a Fulbright Fellow, a Ford Foundation Fellow, a Frankel Fellow at the University of Michigan. She has been awarded grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Mellon Foundation. She is a Korean American who grew up in Los Angeles in and around Koreatown.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Blue Notes of Sampling–Primus Luta

Remixing Girl Talk: The Poetics and Aesthetics of Mashups–Aram Sinnreich

A Tribe Called Red Remixes Sonic Stereotypes–Christina Giacona

A Manifesto, or Sounding Out!’s 51st Podcast!!!

This week, Sounding Out! dropped its 51st podcast episode. As the curator and producer, I thought it necessary to commemorate the occasion with some fanfare. I want to shout from the hilltops about how proud I am that our little podcast has turned 51!

Erm…at least I’m posting about it.

Also, I want to clear the air a little about what it is that we do. I’ve received feedback here and there over the years about the sound of our podcasts, that we sound “different” and/or “inconsistent,” that we need to normalize the sound a bit: hello out there, audiophiles! Today, I want to say, once and for all, that our sound is intentional and that we are proud of it, hiss, distortion, and all! We think what some hear as “imperfections” are all part of what sets us apart from the ever-growing pack of podcasters. SO!’s podcast has sounded different since we MacGyvered our first episode from an epic talk, a few great ideas, and a rogue tape recorder at River Read Books in Binghamton, NY in April, 2011.

The Sounding Out! Podcast began as a series of conversations within the editorial team back in 2011. We knew that the blog was “talking the talk” in new, excellent, and often provocative ways, but that something was missing to keep pushing the form into the red, not just the content. We knew we needed something more—a little snap, crackle, and pop, if you will—a way to show how Sounding Out! was always listening, and a way for thinkers, artists, provocateurs, and more to engage with sound more directly. In 2011, podcasts were accumulating in the shadows waiting to lunge forth to center stage. They seemed really cool, but there were relatively few, and fewer still (if any at all) on the topic of sound studies. Even though we knew that podcasts were going to be a big thing eventually, we had no idea that they would blow up so quickly.

Image by Sandor Weisz @Flickr CC BY-NC.

While we flipped around many ideas, we decided to put our energies behind what was then an occasional series of podcasts that allowed us to capture important yet fleeting moments—too quick and dirty to really transcribe. While our our initial vision for the podcast was to capture these rare and powerful moments, over the past 5 years we have kept this mission consistent while evolving to better accommodate artists and theorists alike. During that time we have hosted mystics and librarians, shared fieldwork from São Paolo, Brazil to Lodi, Ohio, interviewed theremin players and visionaries. See the full list of episodes here. Even though our content has been wide ranging and eclectic, we’ve made it a point to privilege access and immediacy in all of our episodes.

As I listen back to the past five years, I realize that our contribution to the fields of sound studies and podcasting has not just been in terms of who we broadcast and what we amplify, but through the sound of our podcasts themselves. Our podcasts don’t sound perfect. They’re spiritually aligned by the raw production ethic of bands like The Minutemen, who always privileged the emotive qualities of immediacy, access, and intimacy over the brooding qualities of studio production. Particularly because we founded the podcast upon these same principles, I have strived to prioritize radical visions and ideas and to amplify new voices above all else. I want each podcast to arrive in your queue like a wrapped gift—topic, content, production, and sound all equally mysterious. Some of our podcasts were recorded on cellphones and others were recorded in high-end studios and recording booths. Our 51st anniversary isn’t the perfect occasion, either. But, hey, we’re proud of these audible distortions.

“The Minutemen: #1 Hit Song”

So what do I mean that our podcast sounds different? Well, I mean two things: First, we sound different than what episodic radio sounds like. Our DIY—or, more accurately, we will help you “Do It Yourself”—ethics deliberately dial back radio’s genre conventions: smooth identifiable hosts, heavy compression, sound-proof rooms with the latest in equipment. We encourage and construct our podcast with a deliberate sonic diversity, providing little sonic consistency from episode to episode in order to challenge regimes of production that threaten to make all recordings sound the same. We have many many different announcers and hosts; for this podcast to be the space of radical discourse that we intend, it’s important to cast our net wide. This isn’t to say that we don’t care about “quality,” but rather that we define quality differently. Rather than an audiophilic emphasis on the sorts of tone found most frequently in microphone technique, sound booths, and—when all else fails—postproduction, we believe that a “quality” podcast—particularly one about sound—should explore sounds that we rarely hear and allow its artists freedom over how they present their work.

I curate our podcast as a sonic refuge from the invisible regime of auditory production that has slowly constricted and strangled radio this past century. And I’m proud to share podcasts that have been recorded on in impromptu circumstances, Episode XXXIX: Soundwalking Davis, CA and New Brunswick, NJ, for example. We want artists to show more than they tell; Episode XII: Animal Transcriptions, Listening to the Lab of Ornathology is a perfect example of this. Here Jonathan Skinner’s brilliant exploration of animal sounds perfectly balances sound and interview and invites listeners to compare sounds to speech, and vice versa. Another example of this ethic is film professor Monteith Mccollum’s remix of the original War of the Worlds broadcast. Although Mccollum offers some commentary at the start of the recording, what follows is a unique and dazzling sonic experience. Giving radical ideas both the space and platform to be heard is this podcast’s mission. So far, so good!

The second way our podcast sounds different has to do with our deliberate curatorial resistance to consistency between our episodes. When programs bend to the whims of genre conventions, creativity is all but snuffed out. For our podcast to excel as a form for sharing visions, ideas, and experiments, we must allow our composers, authors, and auditors the freedom to explore sonic space. We celebrate Sounding Out!’s anniversary annually with a series of mixes hand-picked by our stable of authors (Listen to years 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 here!), we’ve entertained interviews, panels, and sound art alike. You may have missed it, but we even have an episode diving into the work of ambient sound in a Dungeons and Dragons game.

Behind the scenes, we look NOTHING like this. Image borrowed from fr4dd @Flickr CC BY.

While I do think about the sound of our podcast aesthetically—I used to run a music production studio out from the trunk of my car—we do not cultivate a DIY anything-goes ethic strictly for a “cool factor” or just for its own sake. Rather, we have calibrated our different sonic approach in deliberate defiance of styles of production which are all too frequently celebrated within the cultures of straight white men. (Check out SO! Editor-in-Chief Jennifer Lynn Stoever’s epic three-part treatise on the tape recorder in popular film to glean some sense of the tape-recorder’s role as an instrument of masculine control. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3). The standards of taste which have long governed the domain of radio production (and audio production, as a whole) are historically connected to the communities of practice which have occupied invisible yet powerful roles as audio producers, engineers, critics, and marketers.

As Jonathan Sterne explains in MP3, the science of audio fidelity has historical roots within a corporate logic that privileges sounds that are easily shared through telephone cables. “AT&T encountered hearing as an economic problem once its options for extracting additional profit through price were limited,” Sterne says, “Among other strategies, it sought to learn which frequencies could be excluded from the market for telephone signals” (14). In other words, the entire craft of audio engineering has historical roots in privileging sounds that make money above all else. Not only this, but the standards of fidelity cultivated by engineers allow them to gatekeep and demand money at the outset, blocking access to the means of production. These standards are more often than not embedded within the cultures of listening and sales fostered by the radio industry. Fortunately, podcasts have been able to challenge many of these genre tropes, We’re proud to contribute to this momentum and to propel it forward as we continue our series. And we’re not stopping! Up on deck in 2016 we have some amazing compositional sound art, more from Marcella Ernest’s trek to uncover lost sounds, and some notes on a forthcoming project in archiving one city’s local music scene.

BOOM!!!!! Image by Jamie McCaffrey CC @Flickr BY-NC.

So, in the spirit of Sounding Out!’s annual blog-o-versary we’re popping the cork for our podcast’s 50th episode with a few of the milestones we hit this past five years.

We found a theme song. This was a small but important step in our development. What would a podcast about sound be without some kind of awesome anthem representing it? (Nothing, that’s what!) We need to officially thank the members of Hunchback (Miranda, Mike, Jay, and Craig) for donating their song “Feeling Blind” to our podcast. Hunchback was a legendary horror-surf band from the NJ basement scene who endeavored to produce highly visceral sonic experiences of the highest caliber in their songwriting. You can still find a ton of their recordings on the internet. Thanks, crew!

We got listed on iTunes and Stitcher. It bears mentioning that quite a bit of technical muscle is involved in establishing a podcast. We would have gotten nowhere without Andreas Duus Pape’s help and guidance during our earliest moments. Andreas was instrumental in opening up the hood of the podcast and making it purr. Not only did he donate his time to plug us into iTunes’ network of podcasts, but he also shared some excellent philosophical thoughts on the topic. You can listen here and read them here.

We got listed on iTunes and Stitcher. It bears mentioning that quite a bit of technical muscle is involved in establishing a podcast. We would have gotten nowhere without Andreas Duus Pape’s help and guidance during our earliest moments. Andreas was instrumental in opening up the hood of the podcast and making it purr. Not only did he donate his time to plug us into iTunes’ network of podcasts, but he also shared some excellent philosophical thoughts on the topic. You can listen here and read them here.

We went monthly. Originally we had conceived the podcast as more a haphazard, occasional treat for our readers. Slowly but surely as demand and interest grew, we began to carve out a more regular calendar space for our podcast. First we switched to a bi-monthly format, and then we started with monthly broadcasts. Can’t slow this beat down.

We are the sonic archive of a sound art conference. That’s right, we featured sonic mixdowns of the entire Tuned City of Brussels sound art festival. Over the course of the festivals three days, we featured daily mixdowns of the prior day’s key sounds and moments. Each mixdown is brilliant and a testiment to the raw passion of our podcast contributors. They worked round the clock to produce such an amazing series. Check out the night before, and days 1, 2, and 3.

We produced a LOT of soundwalks. If you’re a listener you know that we love our soundwalks. We’re proud to be host to play host to a variety of soundwalks from cities around the world. Last month’s Yoshiwara soundwalk by Gretchen Ju challenged listeners to critically engage with the city’s fraught history of sex work. Other contributors in our soundwalk series like James Hodges have considered how the ambient music of big box stores and shopping malls are part of the architecture of commerce. Finally others like Frank Bridges have taken us to the edge of history and soundwalked the grounds of Thomas Edison’s workshop in Edison, NJ. No matter what the locale, our soundwalks are part of our podcast’s signature.

We produced a LOT of soundwalks. If you’re a listener you know that we love our soundwalks. We’re proud to be host to play host to a variety of soundwalks from cities around the world. Last month’s Yoshiwara soundwalk by Gretchen Ju challenged listeners to critically engage with the city’s fraught history of sex work. Other contributors in our soundwalk series like James Hodges have considered how the ambient music of big box stores and shopping malls are part of the architecture of commerce. Finally others like Frank Bridges have taken us to the edge of history and soundwalked the grounds of Thomas Edison’s workshop in Edison, NJ. No matter what the locale, our soundwalks are part of our podcast’s signature.

We found a regular contributor. Regular contributors are the heart and soul of Sounding Out! They lead the conversation on sound and work to bring you the best, most interesting content. For these reasons we’re proud to announce that Marcella Ernest will be joining our podcast as a regular contributor with her series “Searching for Lost Sounds.” Marcella will be interviewing a variety of sonic practitioners in an effort to give voice to the voiceless. Her most recent entry in the series was posted last Thursday. You can listen here.

We’re going to keep it coming. That’s our promise to you! We’ll be producing great content as long as you’re listening. Take a moment to subscribe to our iTunes or Stitcher accounts and also explore our Episode Guide to see if you missed anything this past 5 years. It’s been a rewarding adventure so far and we guarantee that we’ve already got some great content lined up in the coming months.

Image by Sandor Weisz @Flickr CC BY-NC.

–

Aaron Trammell is a Provost’s Postdoctoral Scholar for Faculty Diversity in Informatics and Digital Knowledge at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. He earned his doctorate from the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information in 2015. Aaron’s research is focused on revealing historical connections between games, play, and the United States military-industrial complex. He is interested in how military ideologies become integrated into game design and how these perspectives are negotiated within the imaginations of players. He is the Co-Editor-in-Chief of the journal Analog Game Studies and the Multimedia Editor of Sounding Out!

–

Featured image is “Roscoe Considers Recording a Podcast” by zoomar @Flickr CC BY-NC.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #1: Peter DiCola at River Read Books – Peter DiCola

It’s Our Blog-O-Versary — Jennifer Lynn Stoever

Sounding Out! Podcast #51: Creating New Words from Old Sounds – Marcella Ernest

Recent Comments