Your Voice is (Not) Your Passport

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It kicked off with Amina Abbas-Nazari’s post, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice. Last week, Golden Owens took a deep historical dive into the racialized sound of servitude in America and how this impacts Intelligent Virtual Assistants. Today, Michelle Pfeifer explores how some nations are attempting to draw sonic borders, despite the fact that voices are not passports.–JS

—

In the 1992 Hollywood film Sneakers, depicting a group of hackers led by Robert Redford performing a heist, one of the central security architectures the group needs to get around is a voice verification system. A computer screen asks for verification by voice and Robert Redford uses a “faked” tape recording that says “Hi, my name is Werner Brandes. My voice is my passport. Verify me.” The hack is successful and Redford can pass through the securely locked door to continue the heist. Looking back at the scene today it is a striking early representation of the phenomenon we now call a “deep fake” but also, to get directly at the topic of this post, the utter ubiquity of voice ID for security purposes in this 30-year-old imagined future.

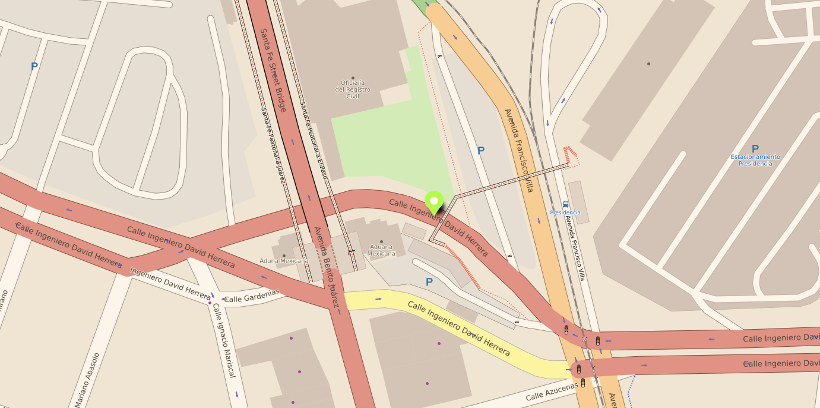

In 2018, The Intercept reported that Amazon filed a patent to analyze and recognize user’s accents to determine their ethnic origin, raising suspicion that this data could be accessed and used by police and immigration enforcement. While Amazon seemed most interested in using voice data for targeting users for discriminatory advertising, the jump to increasing surveillance seemed frighteningly close, especially because people’s affective and emotional states are already being used for the development of voice profiling and voice prints that expand surveillance and discrimination. For example, voice prints of incarcerated people are collected and extracted to build databases of calls that include the voices of people on the other end of the line.

“Collect Calls From Prison” by Flickr User Cobalt123 (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What strikes me most about these vocal identification and recognition technologies is how their appeal seems to lie, for advertisers, surveillers, and policers alike that voice is an attractive method to access someone’s identity. Supposedly there are less possibilities to evade or obfuscate identification when it is performed via the voice. It “is seen as a solution that makes it nearly impossible for people to hide their feelings or evade their identities.” The voice here works as an identification document, as a passport. While passports can be lost or forged, accent supposedly gives access to the identity of a person that is innate, unchanging, and tied to the body. But passports are not only identification documents. They are also media of mobility, globally unequally distributed, that allow or inhibit movement across borders. States want to know who crosses their borders, who enters and leaves their territory, increasingly so in the name of security.

What, then, when the voice becomes a passport? Voice recognition systems used in asylum administration in the Global North show what is at stake when the voice, and more specifically language and dialect, come to stand in for a person’s official national identity. Several states including Denmark, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Sweden, as well as Australia and Canada have been experimenting with establishing the voice, or more precisely language and dialect, to take on the passport’s role of identifying and excluding people.

In the 1990s—not too far from the time of Sneakers release—they started to use a crude form of linguistic analysis, later termed Language Analysis for the Determination of Origin (LADO), as part of the administration of claims to asylum. In cases where people could not provide a form of identity documentation or when those documents would be considered fraudulent or inauthentic, caseworkers would look for this national identity in the languages and dialects of people. LADO analyzes acoustic and phonetic features of recorded speech samples in relation to phonetics, morphology, syntax, and lexicon, as well as intonation and pronunciation.

The problems and assumptions of this linguistic analysis are multiple as pointed out and critiqued by linguists. 1) it falsely ties language to territorial and geopolitical boundaries and assumes that language is intimately tied to a place of origin according to a language ideology that maps linguistic boundaries onto geographical boundaries. Nation-state borders on the African continent and in the Middle East were drawn by colonial powers without considerations of linguistic communities. 2) LADO thinks of language and dialect as static, monoglossic and a stable index of identity. These assumptions produce the idea of a linguistic passport in which language is supposed to function as a form of official state identification that distributes possibilities and impossibilities of movement and mobility. As a result, the voice becomes a passport and it simultaneously functions as a border, by inscribing language into territoriality. As Lawrence Abu Hamdan has written and shown through his sound art work The Freedom of Speech itself, LADO functions to control territory, produce national space, and attempts to establish a correlation between voice and citizenship.

I’ll add that the very idea of a passport has a history rooted in forms of colonial governance and population control and the modern nation-state and territorial borders. The body is intimately tied to the history of passports and biometrics. For example, German colonial administrators in South-West Africa, present day Namibia, and German overseas colony from 1884 to 1919 instituted a pass batch system to control the mobility of Indigenous people, create an exploitable labor force, and institute and reinforce white supremacy and colonial exploitation. Media and Black Studies scholar Simone Browne describes biometrics as “digital epidermalization,” to describe how surveillance becomes inscribed and encoded on the skin. Now, it’s coming for the voice too.

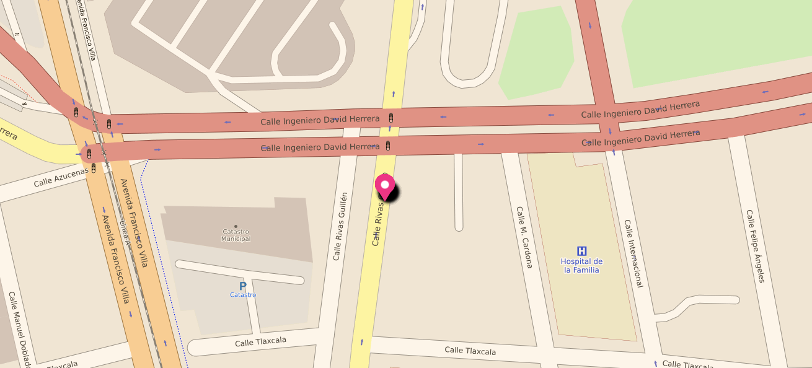

In 2016 the German government took LADO a step further and started to use what they call a voice biometric software that supposedly identifies the place of origin of people who are seeking asylum. Someone’s spoken dialect is supposedly recognized and verified on the basis of speech recordings with an average lengths of 25,7 seconds by a software employed by the German Ministry for Migration and Refugees (in German abbreviated as BAMF). The now used dialect recognition software used by German asylum administrators distinguishes between 4 large Arabic dialect groups: Levantine, Maghreb, Iraqi, Egyptian, and Gulf dialect. Just recently this was expanded with language models for Farsi, Dari and Pashto. There are plans to expand this software usage to other European countries, evidenced by BAMF traveling to other countries to demonstrate their software.

This “branding” of BAMF’s software stands in stark contradiction to its functionality. The software’s error rate is 20 percent. It is based on a speech sample as short as 26 seconds. People are asked to describe pictures while their speech is recorded, the software then indicates a percentage of probability of the spoken dialect and produces a score sheet that could indicate the following: 74% Egyptian, 13% Levantine, 8% Gulf Arabic, 5 % Other. The interpretation of results is left to the caseworkers without clear instructions on how to weigh those percentages against each other. The discretion left to caseworkers makes it more difficult to appeal asylum decisions. According to the Ministry, the results are supposed to give indications and clues about someone’s origin and are not a decision-making tool. However, as I have argued elsewhere, algorithmic or so-called “intelligent” bordering practices assume neutrality and objectivity and thereby conceal forms of discrimination embedded in technologies. In the case of dialect recognition the score sheet’s indicated probabilities produce a seeming objectivity that might sway case-workers in one direction or another. Moreover, the software encodes distinctions between who is deserving of protection and who is not; a feature of asylum and refugee protection regimes critiqued by many working in the field.

The functionality and operations of the software are also intentionally obscured. Research and sound artist Pedro Oliveira addresses the many black-boxed assumptions entering the dialect recognition technology. For instance, in his work Das hätte nicht passieren dürfen he engages with the labor involved in producing sound archives and speech corpora and challenges “ the idea that it might be feasible, for the purposes of biometric assessment, to divorce a sound’s materiality from its constitution as a cultural phenomenon.” Oliveira’s work counters the lack of transparency and accountability of the BAMF software. Information about its functionality is scarce. Freedom of information requests and parliamentary inquiries about the technical and algorithmic properties and training data of the software were denied as the information was classified because “the information can be used to prepare conscious acts of deception in the asylum proceeding and misuse language recognition for manipulation,” the German government argued. While it is not necessarily deepfakes like the one Brandes produced to forego a security system that the German authorities are worried about, the specter of manipulation of the software looms large.

The consequences of the software’s poor functionality can have drastic consequences for asylum decisions. Vice reported in 2018 the story of Hajar, whose name was changed to protect his identity. Hajar’s asylum application in Germany was denied on the basis of a dialect recognition software that supposedly indicated that he was a Turkish speaker and, thus, could not be from the Autonomous Region Kurdistan as he claimed. Hajar who speaks the Kurdish dialect Sorani had been instructed by BAMF to speak into a telephone receiver and describe an image in his first language. The software’s results indicated a 63% probability that Hajar speaks Turkish and the caseworker concluded that Hajar had lied in his asylum hearings about his origin and his reasons to seek asylum in Germany who continued to appeal the asylum decision. The software is not equipped to verify Sorani and should not have been used on Hajar in the first place.

Why the voice? It seems that bureaucrats and caseworkers saw it as a way to identify people with ease and scale language analysis more easily. It is also important to consider the context in which this so-called voice biometry is used. Many people who seek asylum in Germany cannot provide identity documents like passports, birth certificates, or identification cards. This is the case because people cannot take them with them as they flee, they are lost or stolen on people’s journeys, or they are confiscated by traffickers. Many forms of documentation are also not accepted as legitimate by state authorities. Generally, language analysis is used in a hostile political context in which claims to asylum are increasingly treated with suspicion.

The voice as a part of the body was supposed to provide an answer to this administrative problem of states. In response to the long summer of migration in 2015 Germany hired McKinsey to overhaul their administrative processes, save money, accelerate asylum procedures, and make them more “efficient.” In July 2017, the head of the Department for Infrastructure and Information Technology of the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees hailed the office’s new voice and dialect recognition software as “unrivaled world-wide” in its capacity to determine the region of origin of asylum seekers and to “detect inconsistencies” in narratives about their need for protection. More than identification documents, personal narratives, or other features of the body, the voice, the BAMF expert suggests is the medium that allows for the indisputable verification of migrants’ claims to asylum, ostensibly pinpointing their place of origin.

Voice and dialect recognition technology are established by policy makers and security industries as particularly successful tools to produce authentic evidence about the origin of asylum seekers. Asylum seekers have to sound like being from a region that warrants their claims to asylum: requiring the translation of voices into geographical locations. As a result, automated dialect recognition becomes more valuable than someone’s testimony. In other words, the voice, abstracted into a percentage, becomes the testimony. Here, the software, similarly to other biometric security systems, is framed as more objective, neutral, and efficient way of identifying the country of origin of people as compared to human decision-makers. As the German Migration agency argued in 2017: “The IT supported, automated voice biometric analysis provides an independent, objective and large-scale method for the verification of the indicated origin.”

The use of dialect recognition puts forth an understanding of the voice and language that pinpoints someone’s origin to a certain place, without a doubt and without considering how someone’s movement or history. In this sense, the software inscribes a vision of a sedentary, ahistorical, static, fixed, and abstracted human into its operations. As a result, geographical borders become reinforced and policed as fixed boundaries of territorial sovereignty. This vision of the voice ignores multiple mobilities and (post)colonial histories and reinscribes the borders of nation-states that reproduce racial violence globally. Dialect recognition reproduces precarity for people seeking asylum. As I have shown elsewhere, in the absence of other forms of identification and the presence of generalized suspicion of asylum claims, accent accumulates value while the content of testimony becomes devalued. Asylum applicants are placed in a double bind, simultaneously being incited to speak during asylum procedures and having their testimony scrutinized and placed under general suspicion.

Similar to conventional passports, the linguistic passport also represents a structurally unequal and discriminatory regime that needs to be abolished. The software was framed as providing a technical solution to a political problem that intensifies the violence of borders. We need to shift to pose other questions as well. What do we want to listen to? How could we listen differently? How could we build a world in which nation-states and passports are abolished and the voice is not a passport but can be appreciated in its multiplicity, heteroglossia, and malleability? How do we want to live together on a planet increasingly becoming uninhabitable?

—

Featured Image: Voice Print Sample–Image from US NIST

—

Michelle Pfeifer is postdoctoral fellow in Artificial Intelligence, Emerging Technologies, and Social Change at Technische Universität Dresden in the Chair of Digital Cultures and Societal Change. Their research is located at the intersections of (digital) media technology, migration and border studies, and gender and sexuality studies and explores the role of media technology in the production of legal and political knowledge amidst struggles over mobility and movement(s) in postcolonial Europe. Michelle is writing a book titled Data on the Move Voice, Algorithms, and Asylum in Digital Borderlands that analyses how state classifications of race, origin, and population are reformulated through the digital policing of constant global displacement.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Hey Google, Talk Like Issa”: Black Voiced Digital Assistants and the Reshaping of Racial Labor–Golden Owens

Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication –Amina Abbas-Nazari

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–Steph Ceraso

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

The Sonic Roots of Surveillance Society: Intimacy, Mobility, and Radio–Kathleen Battles

Acousmatic Surveillance and Big Data–Robin James

Recent Comments