Listening to and as Contemporaries: W.E.B. Du Bois & Sigmund Freud

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter-Ényì, Austin Richey, Julie Beth Napolin, and Vanessa Valdés, move us toward a decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it. To start the series from the beginning, click here.

Readers, today’s post (the first of an interwoven trilogy of essays) by Julie Beth Napolin explores Du Bois and Freud as lived contemporaries exploring entangled notions of melancholic listening across the Veil.

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

When W.E.B. Du Bois began the first essay of The Souls of Black Folk (1903) with a bar of melody from “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See,” he paired it with an epigraph taken from a poem by Arthur Symons, “The Crying of Water”:

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea,

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.

A listener, the poem’s speaker can’t be sure of the source of the sound, whether it is inward or outward. Something of its sound is exiled and resonates with Symons’ biographical position as a Welshman writing in English, an imperial tongue. At the heart of the poem is a meditation on language, communication, and listening. Personified, the water longs to be understood and sounds out the listener’s own interiority that struggles to be communicated. The poem’s speaker hears himself in the water, but he is nonetheless divided from it. If he could understand the source of the sound in a suppressed or otherwise unavailable memory, the speaker might be put back together. But listening all night long, that understanding does not come.

Démontée, Image by Flickr User Alain Bachellier

Together, the poem and song serve as a circuitous opening to Du Bois’ “Of Our Spiritual Strivings,” an essay that grounds itself in Du Bois’ training as a sociologist to detail “the color line,” which Du Bois takes to be the defining problem of 20th century America. The color line is not simply a social and economic problem of the failed projects of Emancipation and Reconstruction, but a psychological problem playing out in what Du Bois is quick to name “consciousness.” As the first African American to receive a PhD from Harvard in 1895, Du Bois had studied with psychologist William James, famous for coining the phrase “the stream of thought” in his modernist opus, The Principles of Psychology (1890). In her study of pragmatism and politics in Du Bois, Mary Zamberlin describes how James encouraged his students to listen to lectures in the way that one “receives a song” (qtd. 81). In his techniques of writing, Du Bois adopts and reinforces the paramount place of intuition and receptivity in James’ thought to conjoin otherwise opposed concepts. Demonstrated by the opening epigraphs themselves, Du Bois’ techniques often trade in a lyricism that stimulates the reader’s multiple senses.

I argue that Du Bois surpasses James by thinking through listening consciousness in its relationship to what we now call trauma. While I will remark upon the specific place of the melody in Du Bois’ propositions, I want to focus on the more generalized opening of his book in the sounds of suffering, crying, and what Jeff T. Johnson might call “trouble.” The contemporary understanding of trauma, as a belated series of memories attached to experiences that could not be fully grasped in their first instance, comes to us not from the scientific discipline of psychology, but rather psychoanalysis.

Among the field’s first progenitors, Sigmund Freud, was a contemporary of Du Bois. Though trained as a medical doctor, Freud sought to free the concept of the psyche from its anatomical moorings, focusing in particular on what in the human subject is irrational, unconscious, and least available to intellectual mastery. His thinking of trauma became most pronounced in the years following WWI, when he observed the consequences of shell-shock. Freud discovered a more generalizable tendency in the subject to go over and repeat painful experiences in nightmares. Traumatic repetition, he noted, is a subject struggling to remember and to understand something incredibly difficult to put into words. At the heart of Freud’s methods, of course, was listening and the observations it afforded, grounding his famous notion of the “talking cure.” Because trauma is so often without clear expression, Freud listened to language beyond meaning, beyond what can be offered up for scientific understanding.

Image by Flicker User Khuroshvili Ilya

The beginning of Souls, along with its final chapter on “sorrow songs,” slave song or spirituals, tells us that Du Bois’ project shared that same auditory core. Du Bois was listening to consciousness, that is, developing a theory of a listening (to) consciousness in an attempt to understand the trauma of racism and the long, drawn-out historical repercussions of slavery. Importantly, however, Du Bois’ meditation on trauma precedes Freud’s. But Du Bois’ thinking also surpasses Freud in beginning from the premise that trauma is the sine qua non of theorizing racism, which makes itself felt not only outwardly in social and economic structures, but inwardly in consciousness and memory.

Du Bois claimed that he hadn’t been sufficiently Freudian in diagnosing white racism as a problem of irrationality. He didn’t mean by this that Freud himself made such a diagnosis, but rather that Freud was correct in refusing to underestimate what is least understandable about people. Freud’s thinking, however, remained mired in racist thinking of Africa. Though he claimed to discover a universal subject in the structure of the psyche—no one is free from the unconscious—racist thinking provided the language for the so-called “primitive” part of the human being in drives. This primitivism shaped Freud’s myopic thinking of female sexuality, famously remarking that female sexuality is the “Dark Continent,” i.e. unavailable to theory. Freud drew the phrase from the imperialist travelogues of Henry Morton Stanley in the same moment that Du Bois was turning to Africa to find what he called, both with and against Hegel, a “world-historical people.” As I argue, Du Bois found in the music descended from the slave trade not only a “gift” and “message” to the world, but the ur-site for theorizing trauma.

Ranjana Khanna has shown how colonial thinking was the precondition for Freudian psychoanalysis. Anti-colonial psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, for example, both took up and resisted Freud when he elaborated the effects of racism as the origin of black psychopathology, i.e. feelings of being split or divided. Du Bois, like Fanon after him, was hearing trauma politically as a structural event. The complex intellectual biography of Du Bois, which includes a time of studying (in German) at Berlin’s Humboldt University, mandated that he took from European philosophical interlocutors what he needed, creating a hybrid yet decidedly new theory of listening consciousness. That hybridity is exemplified by the opening of his book, an antiphony between two disparate sources bound to each other across the Atlantic through what I will call hearing without understanding. In this post, I ask what Du Bois can tell us about psychoanalytic listening and its ongoing potential for sound studies and why Freud had difficultly listening for race.

***

“Before the Storm,” Image by Flickr User Marina S.

“Psychoanalysis . . . , more than any twentieth-century movement,” writes Eli Zaretsky in Political Freud, “placed memory at the center of all human strivings toward freedom” (41). He continues, “By memory I mean no so much objective knowledge of the past or history but rather the subjective process of mastering the past so that it becomes part of one’s identity.” In 1919, Freud gave a name to the experience resounding for Du Bois in Symons’ poem “The Crying of Water:” “melancholia.” Unlike mourning after the death of a loved one, whose aching and cries pass with time, melancholia is an ongoing, integral part of subjects who have lost more inchoate things, such as nation or an ideal. This loss, Freud contended, could in fact be constitutive of identity, or the “ego,” Latin for “I” (“is it I? Is it I?” Symons asks). In mourning, one knows what has been lost; in melancholia, one can’t totally circumscribe its contours.

Zaretsky details the way that Freudianism, particularly after its rapid expansion in the US after WWI, became a resource for the transformation of African American political and cultural consciousness, playing a pronounced role in the Harlem Renaissance, the Popular Front, and anti-imperialist struggles. Zaretsky rightly positions Du Bois and his 1903 text as the beginning of a political and cultural transformation, but it is an anachronism to suggest that Freudianism contributed to Du Bois’ early work. Not only does Du Bois’ analysis of “The Crying of Water” predate Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” by nearly two decades, the two thinkers were contemporaries. In the years that Freud was writing his letters to Wilhelm Fliess, which became the body of his first book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Du Bois was compiling his previous publications for The Souls of Black Folk, along with writing a new essay to conclude it, “The Sorrow Songs,” a sustained reflection on melancholia and its cultural reverberations in song. 1903 is the year of Souls compilation, not composition.

Du Bois’ thinking of a racialized listening consciousness is not only contemporary to Freud, but also fulfills and outstrips him. To approach Du Bois and Freud as contemporaries involves positioning them as listeners on different, but not opposing sides of what Du Bois calls the “Veil.” It is the psychological barrier traumatically instantiated by racialization, which Du Bois famously describes in the first chapter of Souls. The Veil, Jennifer Stoever describes, is both a visual and auditory figure, the barrier through which one both sees and hears others.

To better define the Veil, Du Bois—like Frederick Douglass before him—returns to a painful childhood scene that inscribed in his memory the violence of racial difference and social hierarchy. Early works of African American literature often turn to memoir, writing their elided subjectivity into history. But we miss something if we don’t recognize there a proto-psychoanalytic gesture. In the middle of a sociological, political essay, Du Bois writes of the painful memory of a little white girl rejecting his card, a gift. In this, we can recognize the essential psychoanalytic gesture of returning to the traumatic past of the individual as a forge for self-actualization in the present.

“Storm Coming Our Way” by Flickr User John

As Paul Gilroy has described, Du Bois’ absorption of Hegel’s thought while at Humboldt cannot be underestimated, particularly in terms of the famous master-slave dialectic. In this dialectic, the slave-consciousness emerges as victorious because the master depends on him for his own identity, a struggle that Hegel described as taking place within consciousness. Like Hegel, Zaretsky notes, Du Bois understood outward political struggle to be bound to “internal struggle against . . . psychic masters” (39). I would state this point differently to note that Du Bois’ traumatic experience as a raced being had already taught him the Hegelian maxim: the smallest unit of being is not one, but two. For Hegel, the slave knows something the master doesn’t: I am only complete to the extent that I recognize the other in myself and that the other recognizes me in herself. That is the essential lesson that an adult Du Bois gleans from the memory of the little girl who will not listen to him. He recognizes that she, too, is incomplete.

The essential difference between psychoanalysis and the Hegelian thrust of Du Bois’ essay, however, is that while a traditional analysand seeks individual re-making of the past—not only childhood, but a historical past that shapes an ongoing political present– Du Bois emphasizes the collective and in ways that cannot be reduced to what Freud later calls the “group ego.” If we restore the place of Du Bois at the beginnings of psychoanalysis and its ways of listening to ego formation, then we find that race, rather than being an addendum to its project, is at its core.

We can begin by turning to a paradigmatic scene for psychoanalytic listening, the one that has most often been taken up by sound studies: the so-called “primal scene.” In among the most famous dreams analyzed by Freud, Sergei Pankejeff (a.k.a. the “Wolf Man”) recalls once dreaming that he was lying in bed at night near a window that slowly opened to reveal a tree of white wolves. Silent and staring, they sat with ears “pricked” (aufgestellt). Pricked towards what? The young boy couldn’t hear, but he sensed the wolves must have been responding to some sound in the distance, perhaps a cry.

“The Wolf Man’s Dream” by Sergei Pankejeff, Freud Museum, London

In “The Dream and the Primal Scene” section of “From the History of An Infantile Neurosis” (1914/1918), Freud concluded that the dream was grounded in the young boy’s traumatic experience of witnessing his parents having sex. Calling this the “primal scene,” Freud conjectured that there must have been an event of overhearing sounds the young boy could not understand. In the letters he exchanged with Fliess, Freud had begun to attend to the strange things heard in childhood as the basis for fantasy life and with it, sexuality.

The primal scene is therefore crucial for Mladen Dolar’s theory in A Voice and Nothing More when he pursues the implications of an unclosed gap between hearing and understanding. In the Wolf Man’s case, it is impossible, Freud writes, for “a deferred revision of the impressions…to penetrate the understanding.” In Dolar’s estimation, the deferred relation between hearing and understanding defines sexuality and is the origin of all fantasy life. This gap in impressions cannot be closed or healed, and, for Jacques Lacan it also orients the failure of the symbolic order to bring the imaginary order to language. From this moment forward, psychoanalytic theory argues the subject is “split,” listening in a dual posture for the threat of danger and the promise of pleasure. Following Lacan, Dolar, Michel Chion, and Slavoj Žižek return to the domain of infantile listening—listening that occurs before a person has fully entered into speech and language—to explain the effects of the “acousmatic,” or hearing without seeing.

After Freud, the phrase “primal scene” has taken on larger significance as a traumatic event that, while difficult to compass, nonetheless originates a new subject position that makes itself available to a collective identity and identification. The original meaning of hearing sexual and libidinal signals without understanding them, I would suggest, holds sway. Psychoanalytic modes of listening, particularly if restored to its political origins in racism, offer resources for what it means to listen beyond understanding, but such thinking of race immediately folds into intersectional thinking of gender and sexuality. Consider the place of the traumatic memory of the little girl who rejects the card. In The Sovereignty of Quiet, Kevin Quashie returns to Du Bois’ primal scene to note how the scene takes place in silence, for she rejects it, in Du Bois’ terms, “with a glance.” I want to expand upon this point to note that where there is silence, there is nonetheless listening. Du Bois is listening for someone who will not speak to him; he desires to be listened to and the card—a calling card—figures a kind of address.

Vintage Calling Card, Image by Flickr User Suzanne Duda

It has gone largely unnoticed that, to the extent that the scene is structured by the master-slave dialectic, it is also structured by desire. This scene of trauma is shattering for both boy and girl. The desire coursing through the scene is suppressed in Du Bois’ adult memory in favor of its meaning for him as a political subject. What would it mean to recollect, on both sides, the trace of sexual (and interracial) desire? In “Resounding Souls: Du Bois and the African American Literary Tradition,” Cheryl Wall notes the scant place for black women in the political imaginary of this text. This suppression, I would argue, already begins in the memory of the girl who appears under the sign of the feminine more generally. The fact that she is white, however, casts a greater taboo over the scene and therefore allows more for a suppression of sexuality in his memory. Du Bois emerges as a political agent disentangled from black women—with one notable exception, the maternal, and this exception demands that we listen with ears pricked to “The Sorrow Songs,” as Du Bois’ early contribution to the psychoanalytic theory of melancholia.

Next week, part two will further explore The Souls of Black Folk as a “displaced beginning of psychoanalytic modes of listening,” emphasizing the African melodies once sung by his grandfather’s grandmother that Du Bois’s hears as a child, as “a partial memory and a mode of overhearing.”

—

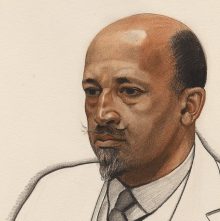

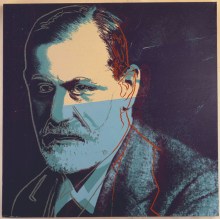

Featured Images: “Nobody Knowns the Trouble I See” from The Souls of Black Folk, Chapter 1, “W.E.B. Du Bois” by Winold Reiss (1925), “Sigmund Freud” by Andy Warhol (1962)

—

Julie Beth Napolin is Assistant Professor of Literary Studies at The New School, a musician, and radio producer. She received a PhD in Rhetoric from the University of California, Berkeley. Her work participates in the fields of sound studies, literary modernism and aesthetic philosophy, asking what practices and philosophies of listening can tell us about the novel as form. She served as Associate Editor of Digital Yoknapatawpha and is writing a book manuscript on listening, race, and memory in the works of Conrad, Du Bois, and Faulkner titled The Fact of Resonance. Her work has appeared in qui parle, Fifty Years After Faulkner (ed. Jay Watson and Ann Abadie), and Vibratory Modernism (ed. Shelley Trower and Anthony Enns).

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“A Sinister Resonance”: Joseph Conrad’s Malay Ear and Auditory Cultural Studies–Julie Beth Napolin

“Scenes of Subjection: Women’s Voices Narrating Black Death“–Julie Beth Napolin

Unsettled Listening: Integrating Film and Place — Randolph Jordan

Look Away and Listen: The Audiovisual Litany in Philosophy

This is an excerpt from a paper I delivered at the 2017 meeting of the Society for Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy.

—

“Compressed and rarefied air particles of sound waves” from Popular Science Monthly, Volume 13. In the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

According to sound studies scholar Jonathan Sterne in The Audible Past, many philosophers practice an “audiovisual litany,” which is a conceptual gesture that favorably opposes sound and sonic phenomena to a supposedly occularcentric status quo. He states, “the audiovisual litany…idealizes hearing (and, by extension, speech) as manifesting a kind of pure interiority. It alternately denigrates and elevates vision: as a fallen sense, vision takes us out of the world. But it also bathes us in the clear light of reason” (15). In other words, Western culture is occularcentric, but the gaze is bad, so luckily sound and listening fix all that’s bad about it. It can seem like the audiovisual litany is everywhere these days: from Adriana Cavarero’s politics of vocal resonance, to Karen Barad’s diffraction, to, well, a ton of Deleuze-inspired scholarship from thinkers as diverse as Elizabeth Grosz and Steve Goodman, philosophers use some variation on the idea of acoustic resonance (as in, oscillatory patterns of variable pressure that interact via phase relationships) to mark their departure from European philosophy’s traditional models of abstraction, which are visual and verbal, and to overcome the skeptical melancholy that results from them. The field of philosophy seems to argue that we need to replace traditional models of philosophical abstraction, which are usually based on words or images, with sound-based models, but this argument reproduces hegemonic ideas about sight and sound.

For Sterne, the audiovisual litany is traditionally part of the “metaphysics of presence” that we get from Plato and Christianity: sound and speech offer the fullness and immediacy that vision and words deny. However, contemporary versions of the litany appeal to a different metaphysics. For example, Cavarero in For More Than One Voice argues that the privileging of vision over sound is the foundation of the metaphysics of presence. “The visual metaphor,” she argues, “is not simply an illustration; rather, it constitutes the entire metaphysical system” (38). The problem with this videocentric metaphysics is that it “legitimates the reduction of whatever is seen to an object” (Cavarero 176) and it cannot “anticipate” or “confirm the uniqueness” of each individual (4). In other words, it objectifies and abstracts, and that’s bad. If vision is the foundation of the metaphysics of presence, one way to fix its problems is to replace the foundation with something else. Cavarero thinks vocal resonance avoids the objectifying and abstracting tendencies that images and text supposedly lend to philosophy.

For Sterne, the audiovisual litany is traditionally part of the “metaphysics of presence” that we get from Plato and Christianity: sound and speech offer the fullness and immediacy that vision and words deny. However, contemporary versions of the litany appeal to a different metaphysics. For example, Cavarero in For More Than One Voice argues that the privileging of vision over sound is the foundation of the metaphysics of presence. “The visual metaphor,” she argues, “is not simply an illustration; rather, it constitutes the entire metaphysical system” (38). The problem with this videocentric metaphysics is that it “legitimates the reduction of whatever is seen to an object” (Cavarero 176) and it cannot “anticipate” or “confirm the uniqueness” of each individual (4). In other words, it objectifies and abstracts, and that’s bad. If vision is the foundation of the metaphysics of presence, one way to fix its problems is to replace the foundation with something else. Cavarero thinks vocal resonance avoids the objectifying and abstracting tendencies that images and text supposedly lend to philosophy.

Similarly, in the same way that the traditional audiovisual litany “assume[s] that sound draws us into the world while vision separates us from it” (Sterne 18), Barad’s argument for agential realism in Meeting the Universe Halfway assumes that diffraction draws theorists into actual contact with matter while “reflection still holds the world at a distance” (87). Agential realism looks is the view that even the most basic units of reality, like the basic particles of matter, exercise agency as they interact to form more complex units; diffraction is Barad’s theory about how these particles interact. This litany of distance-versus-relationality and external objectivity versus immersive materiality structures Barad’s counterpoint between reflection and diffraction. For example, she contrasts traditional investment in reflective surfaces—“the belief that words, concepts, ideas, and the like accurately reflect or mirror the things to which they refer-makes a finely polished surface of this whole affair” (86)–with diffractive interiorities, which get down to “the real consequences, interventions, creative possibilities, and responsibilities of intra-acting within and as part of the world” (37). But how do we know Barad is appealing to an audiovisual litany? We know because her fundamental concept–diffraction–describes the behavior of waveforms as they encounter other things, and 21st century Western scientists and music scholars think sound is a waveform. When two or more waves interact, they produce “alternating pattern[s] of wave intensity” or “increasing and decreasing intensities” (Barad 77), like ripples in water or alternating light frequencies.

Barad appeals to notions of consonance and dissonance to explain how these patterns interact. For example, when diffracting light waves around a razor blade, “bright spots appear in places where the waves enhance one another-that is, where there is ‘constructive interference’-and dark spots appear where the waves cancel one another-that is, where there is ‘destructive interference’” (Barad 77). This “constructive” and “destructive” interference is like audio amplification and masking: when frequencies are perfectly in sync (peaks align with peaks, valleys with valleys), they amplify; when frequencies are perfectly out of sync (peaks align with valleys), they cancel each other out (this is how noise-cancelling headphones work). Constructive interference is consonance: the synced patterns amplify one another; destructive interference is dissonance: the out-of-sync patterns mask each other. Both types of interference are varieties of resonance, a rational or irrational phase relationship among frequencies. Rational phase relationships are ones where the shorter phases or periods of higher frequencies are evenly divisible into the longer phases/periods; irrational phase relationships happen when the shorter phases can’t be evenly divided into the longer wavelengths. Abstracting from waveforms to philosophical analysis, Barad often uses resonance as a metaphor to translate wave behavior into materialist philosophical methods. However, even though most of Barad’s examples throughout Meeting the Universe Halfway are visual, she’s describing what scientists call acoustic relationships.

For example, Barad argues that “diffractively read[ing]” philosophical texts means processing “insights through one another for the patterns of resonance and dissonance they coproduce” (195; emphasis mine). Similarly, she advises her readers to tune into the “dissonant and harmonic resonances” (43) that emerge when they try “diffracting these insights [from an early chapter in her book] through the grating of the entire set of book chapters” (30). As patterns of higher and lower intensity that interact via ir/rational phase relationships, diffraction patterns are a type of acoustic resonance. Appealing to acoustics against representationalism, Barad practices a version of the audiovisual litany. And she’s not the only new materialist to do so—Jane Bennett’s concept of vibration and Elizabeth Grosz’s notion of “music” also ontologize a similar idea of resonance and claim it overcomes the distancing and skeptical melancholy produced by traditional methods of philosophical abstraction.

There are also instances of the audiovisual litany in phenomenology. For example, Alia Al-Saji develops in the article “A Phenomenology of Critical-Ethical Vision” a notion of “critical-ethical vision” against “objectifying vision,” and, via a reading of Merleau-Ponty, grounds the former, better notion of sight (and thought) in his analogy between painting and listening. According to Al-Saji, “objectifying vision” is the model of sight that has dominated much of European philosophy since the Enlightenment. “Objectifying vision” takes seeing as “merely a matter of re-cognition, the objectivation and categorization of the visible into clear-cut solids, into objects with definite contours and uses” (375). Because it operates in a two-dimensional metaphysical plane it can only see in binary terms (same/other): “Objectifying vision is thus reductive of lateral difference as relationality” (390). According to Al-Saji, Merleau-Ponty’s theory of painting develops an account of vision that is “non-objectifying” (388) and relational. We cannot see paintings as already-constituted objects, but as visualizations, the emergence of vision from a particular set of conditions. Such seeing allows us “to glimpse the intercorporeal, social and historical institution of my own vision, to remember my affective dependence on an alterity whose invisibility my [objectifying] vision takes for granted” (Al-Saji 391). Al-Saji turns to sonic language to describe such relational seeing: “more than mere looking, this is seeing that listens (391; emphasis mine).

This Merleau-Pontian vision not only departs from traditional European Enlightenment accounts of vision, it gestures toward traditional European accounts of hearing. Similarly, Fred Evans, in The Multivoiced Body uses voice as a metaphor for the Deleuzo-Guattarian metaphysics that he calls “chaosmos” or “composed chaos” (86); he then contrasts chaosmos to “homophonic” (67) Enlightenment metaphysics. According to Evans, if “‘voices,’ not individuals, the State, or social structures, are the primary participants in society” (256), then “reciprocity” and “mutual intersection” (59) appear as fundamental social values (rather than, say, autonomy). This analysis exemplifies what is at the crux of the audiovisual litany: voices put us back in touch with what European modernity and postmodernity abstract away.

“Image from page 401 of “Surgical anatomy : a treatise on human anatomy in its application to the practice of medicine and surgery” (1901)” by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images

The audiovisual litany is hot right now: as I’ve just shown, it’s commonly marshaled in the various attempts to move past or go beyond stale old Western modernist and postmodernist philosophy, with all their anthropocentrism and correlationism and classical liberalism. To play with Marie Thompson’s words a bit, just as there is an “ontological turn in sound studies,” there’s a “sound turn in ontological studies.” But why? What does sound DO for this specific philosophical project? And what kind of sound are we appealing to anyway?

The audiovisual litany naturalizes hegemonic concepts of sound and sight and uses these as metaphors for philosophical positions. This lets philosophical assumptions pass by unnoticed because they appear as “natural” features of various sensory modalities. Though he doesn’t use this term, Sterne’s analysis implies that the audiovisual litany is what Mary Beth Mader calls a sleight. “Sleights” are, according to Mader in Sleights of Reason,“conceptual collaborations that function as switches or ruses important to the continuing centrality and pertinence of the social category of a political system like “sex” (3). Sleights, in other words, are conceptual slippages that render underlying hegemonic structures like cisheteropatriarchy coherent. More specifically, sleights are “conceptual jacquemarts” (Mader 5). Jacquemarts are effectively the Milli Vanilli of clocks: sounds appear to come from one overtly visible, aesthetically appealing source action (figures ringing a bell) but they actually come from a hidden, less aesthetically appealing source action (hammers hitting gongs). The clock is constructed in a way to “misdirect or misindicate” (Mader 8) both who is making the sound and how they are making it. A sound exists, but its source is misattributed. This is exactly what happens in the uses of the audiovisual litany I discuss above: philosophers misdirect or misindicate the source of the distinction they use the audiovisual litany to mark. The litany doesn’t track the difference between sensory media or perceptual faculties, but between two different methods of abstraction.

Screenshot from Milli Vanilli’s video “Don’t Forget My Number”

This slippage between perceptual medium and philosophical method facilitates the continued centrality of Philosophy-capital-P: philosophy appears to reform its methods and fix its problems, while actually re-investing in its traditional boundaries, values, and commitments. For example, both new materialists and sound studies scholars have been widely critiqued for actively ignoring work on sound and resonance in black studies (e.g., by Zakiyyah Jackson, Diana Leong, Maire Thompson). As Zakiyyah Jackson argues in “Outer Worlds: The Persistence of Race in Movement “Beyond the Human,” new materialism’s “gestures toward the ‘post’ or the ‘beyond’ effectively ignore praxes of humanity and critiques produced by black people” (215), and in so doing ironically reinstitute the very thing new materialism claims to supercede. Stratifying theory into “new” and not-new, new materialist “appeals to move ‘beyond’…may actually reintroduce the Eurocentric transcendentalism this movement purports to disrupt” (Jackson 215) by exclusively focusing on European philosophers’ accounts of sound and sight. Similarly, these uses of the litany often appeal only to other philosophers’ accounts of sound or music, not actual works or practices or performances. They don’t even attend to the sonic dimensions of literary texts, a method that scholars such as Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Alexander Weheliye develop in their work. Philosophers use the audiovisual litany to disguise philosophy’s ugly politics—white supremacy and Eurocentrism—behind an outwardly pleasing conceptual gesture: the turn from sight or text to sound. With this variation of the audiovisual litany, Philosophy appears to cross beyond its conventional boundaries while actually doubling-down on them.

—

Featured image: “soundwaves” from Flickr user istolethetv

—

Robin James is Associate Professor of Philosophy at UNC Charlotte. She is author of two books: Resilience & Melancholy: pop music, feminism, and neoliberalism, published by Zer0 books last year, and The Conjectural Body: gender, race and the philosophy of music was published by Lexington Books in 2010. Her work on feminism, race, contemporary continental philosophy, pop music, and sound studies has appeared in The New Inquiry, Hypatia, differences, Contemporary Aesthetics, and the Journal of Popular Music Studies. She is also a digital sound artist and musician. She blogs at its-her-factory.com and is a regular contributor to Cyborgology.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

From “listening” to “filling in”: where “La Soeur Écoute” Teaches Us to Listen-Emmanuelle Sontag

The Listening Body in Death –Denise Gill

Re-orienting Sound Studies’ Aural Fixation: Christine Sun Kim’s “Subjective Loudness”-Sarah Mayberry Scott

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

- Press Play and Lean Back: Passive Listening and Platform Power on Nintendo’s Music Streaming Service

- “A Long, Strange Trip”: An Engineer’s Journey Through FM College Radio

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments