If You Can Hear My Voice: A Beginner’s Guide to Teaching

Here at Sounding Out! we like to celebrate World Listening Day (July 18) with a blog series. This year, we bring your attention to the role of listening when it comes to the sounds of the K-12 classroom, and by extension, the school.

Here at Sounding Out! we like to celebrate World Listening Day (July 18) with a blog series. This year, we bring your attention to the role of listening when it comes to the sounds of the K-12 classroom, and by extension, the school.

Any day in a K-12 school involves movement and sounds day in and day out: the shuffling of desks, the conversations among classmates, the fire drill alarm, the pencils on paper, the picking up of trays of food. However, in many conversations about schools, teaching, and learning, sound is absent.

This month’s series will have readers thinking about the sounds in classrooms in different ways. They will consider race, class, and gender, and how those aspects intersect how we listen to the classrooms of our past and our present. More importantly, the posts will all include assignments that educators at all stages can use in their classrooms.

Time’s up, pencils down, and if you can hear Caroline Pinkston‘s voice, you should clap once for this personal essay. –Liana Silva, Managing Editor

Editorial Note (7/17/2017, 11:55 am): After careful consideration, I have changed the last photo of the post, as it was from a NATO Flickr account, and it could be seen as supportive of military presence in Afghanistan. I have added a different photo that compliments better the original intention of the author and the editorial mission of SO!.–Liana Silva, Managing Editor

[C]ontrolling who has the floor is the mark of your authority and a necessity to your teaching.

Doug Lemov, Teach Like a Champion: 49 Techniques That Put Students on the Path to College

I am twenty two, new to New York City and new to teaching. In six weeks, I will be in charge of my own classroom, and like most new teachers, I am worried about classroom management. In my summer pedagogy classes I soak up the advice I am given, dutifully taking notes. Controlling my classroom, I learn, means controlling noise: my own and my students’. My words should be clear, carefully chosen, purposeful. I should eliminate words altogether when I can, using hand signals instead: students who need to use the bathroom, for example, can simply raise their hand with two fingers crossed. I should determine when and how students will answer my questions. I should memorize the names of different participation strategies: cold call, popcorn, call and response. Students should not speak out of turn, even if their responses are well intentioned or correct. Even nonverbal sound should be prevented. “Don’t let them suck their teeth at you,” a veteran teacher cautions me. Unsanctioned noise, I learn, can signal rebellion.

I should never, under any circumstances, talk over my students, or let them talk over me. I learn techniques to quiet large groups efficiently. “If you can hear my voice, clap once,” I learn to say. “If you can hear my voice, clap twice.”

On the first days of school, learn to begin many of your sentences with, “You will … “ An alternative would be, “The class procedure is…” The first few days are critical. This cannot be stressed enough.

Harry K. Wong & Rosemary Wong, The First Days of School: How To Be An Effective Teacher

For the first few weeks, I write my lessons in complete sentences, rehearsing them in advance like a play. In the lesson plans I write each night, I attempt to impose order on the noise of the classroom the next day with scripted responses. I plan for periods of speaking and silence. I write out the questions I will ask, giving thought to the most effective wording, and I try to anticipate every possible answer. I think through how I might address a misunderstanding, correct a behavior, dole out consequences. In my lesson plans I speak, students respond, and we go back and forth together.

But in the classroom, noise emerges in less predictable ways, bubbling up through the cracks in ways I haven’t planned for. I am listening for outbursts, students speaking out of turn, challenging my authority: the sorts of sounds I’ve been trained to respond to. But mostly, there are pencils tapping on desks. My tongue tripping over names that are at first unfamiliar to me. My voice, to my dismay, shaking. The door, swinging open and shut. Students arriving late, administrators stepping in: sorry to interrupt but could I borrow…? The fire alarm. The crackling loudspeaker.

My voice is tired and hoarse at the end of each day. The hand signal to use the bathroom does not go over well.

Quiet Power. When you get loud and talk fast, you show that you are nervous, scared, out of control. You make visible all the anxieties and send a message to students that they can control you and your emotions… Though it runs against all your instincts, get slower and quieter when you want control. Drop your voice, and make students strain to listen. Exude poise and calm. (Lemov, Teach Like a Champion)

In October of my first year, something strange happens at the beginning of B period. I’ve come into class a little late, flustered and overwhelmed and tired of pretending so hard that I know what I’m doing, to be calm and authoritative and in control. I open my mouth to say the right words to get class started, but instead I find myself laughing—I’m not sure why, really—and then I can’t stop laughing, and I laugh till I cry a little, and I have to step out into the hallway to compose myself.

Outside, I am sobered by the thought of what I’ve just done: whatever authority and professionalism I had gained, gone. I’ll have to start all over. But when I walk back in, my students are laughing, too, at me, and with me, and through that laughter something tiny but important shifts. It is one of the best days of teaching I’ve had all year.

The soundscape begins to shift. The less I try to extinguish every noise I hear, the more I begin to hear things I hadn’t noticed before: singing in the hallways, laughing. Students asking me about my day.

[K]eep in mind that all students – no matter what age – respond to authenticity. They crave teachers who see them as real people, and they do back flips for the ones whose interactions with them are based on sensitivity and respect. Remember to let them know – this is my single greatest pearl of wisdom, Caroline – let them know every single day that you like them. Laugh with them. Lift their spirits. Sing with them!

(Marsha Russell, personal email).

I observe a veteran teacher whose class of seniors is putty in her hands. At her request, they even burst into song, in unison. How do you get them to do that? I ask. And she tells me: You just have to believe that they will.

She writes me an email of classroom management tips. I print out my favorite part and keep it; I unfold it and I reread it and I put it in my pocket and I pass it along to other teachers.

Sing with them! It’s a revelation, that teaching could be conducting, that learning could be music.

Economy of Language. Fewer words are stronger than more. Demonstrating economy of language shows that you are prepared and know your purpose in speaking. Being chatty or verbose signals nervousness, indecision, and flippancy. It suggests that your words can be ignored. (Lemov, Teach Like a Champion)

My second teaching post is at a private, Episcopal school, where students transition between classes to the sound of music playing through the loudspeakers. In daily chapel, the whole community marks a moment of silence, signaled by a bell that reverberates through the rafters. We sit together patiently, four hundred people breathing. I wonder what combination of school culture and privilege and training creates a student body this quiet and calm, and what unseen tradeoffs might come with such silence. It’s peaceful, but I also find myself nostalgic for the stream of noise I’d grown accustomed to in New York, constant and lively and joyful.

I am finally confident in my ability to quiet a classroom, but the skill proves unhelpful in this new space, where on the first day my seniors sit quietly and wait for me to begin. I find this a little unnerving, like I’ve stepped into a game I thought I knew well, only to find that the rules have changed.

Ineffective teachers say things like:

“Where did we leave off yesterday?”

(Translation: I have no control.)

“Open your books so that we can take turns reading.”

(For what reason?)

“Sit quietly and do the worksheet.”

(To master what?)

“Let’s watch this movie.”

(To learn what?)

“You can have a free period.”

(Translation: I do not have an assignment for you. I am unprepared.)

(Wong & Wong, The First Days of School)

F period teaches me that silence can be deadening, too. They answer when I ask them to, but they wait to be asked, or for one of their classmates to resign themselves to raising their hands, again. And the moment of waiting, the stillness that follows the question, punctures the energy in the room as perfectly as a needle: we arrive at an answer, but something important has been lost along the way.

I’m learning that sometimes controlling noise is easier than producing it, creating sound where before there was silence. And sound is not enough: I must layer speech on top of speech to build a conversation, which is something altogether different and more precious. We have to create something, together. That’s the real challenge.

Teaching isn’t magic, says every classroom management book I’ve ever read. And it isn’t, if you’re talking about technique, about participation strategies, about getting everyone quiet or deciding who speaks. But at the center of all that structure is something elusive and harder to describe or replicate — a moment all those management books try to help you approach, when you and your students arrive at something powerful and important together. I’m not sure that moment requires a lively classroom or a silent one, and I don’t think you can conjure it. It comes unbidden. It might be chance. It might happen like this.

You’ll be in second period English, reading King Lear, at the part when Kent tells Lear to see better. You’ll be telling a story about the very first days of your teaching, when you were too concerned about controlling your classroom to really notice the students in front of you, to see them as real, whole people. You use the story to talk about sight, about what it might mean to see better, how what we pay attention to shapes what we think we know. This story matters to you. You believe in it.

And on this afternoon, for whatever reason, the intensity of your students’ attention will be so sharp and clear it will raise goosebumps on your arms. You’ll feel it and look up, and they will be listening exactly the way you’re talking about seeing, and the room will be so quiet that it almost hums. It’s the kind of quiet you can’t get from silencing noise, just like you can’t create a conversation by making students speak. It grows from the ground up, a momentary enchantment brought on through some alchemy of their interest and your story and the book and the weather that day.

You’ll yield to it, listening, holding your breath in case it disappears.

—

Featured image: “Inside My Classroom” by Flickr user Marie, CC BY-SA 2.0

—

Caroline Pinkston is a PhD candidate in American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Her work brings education into conversation with childhood studies and cultural memory. She holds a B.A. in American Studies and English from Northwestern University (2008), an M.S. in English Education from Lehman College (2010), and an M.A. in American Studies from the University of Texas (2014). A former high school English teacher, she has taught and worked in public, private, and nonprofit settings in New York City and Austin, Texas.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

A Listening Mind: Sound Learning in a Literature Classroom–Nicole Furlonge

Audio Culture Studies: Scaffolding a Sequence of Assignments–Jentery Sayers

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom–Carter Mathes

Technological Interventions, or Between AUMI and Afrocuban Timba

Editors’ note: As an interdisciplinary field, sound studies is unique in its scope—under its purview we find the science of acoustics, cultural representation through the auditory, and, to perhaps mis-paraphrase Donna Haraway, emergent ontologies. Not only are we able to see how sound impacts the physical world, but how that impact plays out in bodies and cultural tropes. Most importantly, we are able to imagine new ways of describing, adapting, and revising the aural into aspirant, liberatory ontologies. The essays in this series all aim to push what we know a bit, to question our own knowledges and see where we might be headed. In this series, co-edited by Airek Beauchamp and Jennifer Stoever you will find new takes on sound and embodiment, cultural expression, and what it means to hear. –AB

Editors’ note: As an interdisciplinary field, sound studies is unique in its scope—under its purview we find the science of acoustics, cultural representation through the auditory, and, to perhaps mis-paraphrase Donna Haraway, emergent ontologies. Not only are we able to see how sound impacts the physical world, but how that impact plays out in bodies and cultural tropes. Most importantly, we are able to imagine new ways of describing, adapting, and revising the aural into aspirant, liberatory ontologies. The essays in this series all aim to push what we know a bit, to question our own knowledges and see where we might be headed. In this series, co-edited by Airek Beauchamp and Jennifer Stoever you will find new takes on sound and embodiment, cultural expression, and what it means to hear. –AB

—

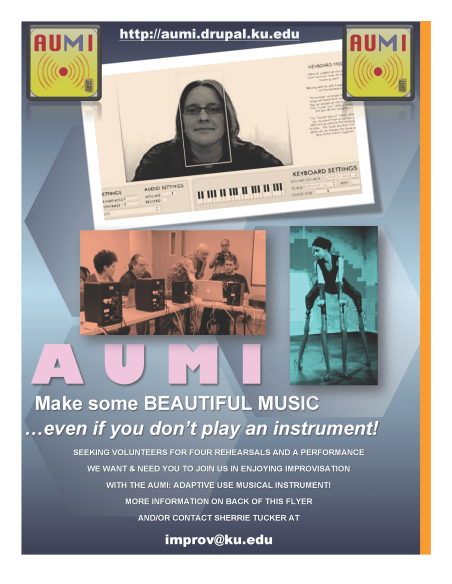

In November 2016, my colleague Imani Wadud and I were invited by professor Sherrie Tucker to judge a battle of the bands at the Lawrence Public Library in Kansas. The battle revolved around manipulation of one specific musical technology: the Adaptive Use Musical Instruments (AUMI). Developed by Pauline Oliveros in collaboration with Leaf Miller and released in 2007, the AUMI is a camera-based software that enables various forms of instrumentation. It was first created in work with (and through the labor of) children with physical disabilities in the Abilities First School (Poughkeepsie, New York) and designed with the intention of researching its potential as a model for social change.

AUMI Program Logo, University of Kansas

Our local AUMI initiative KU-AUMI InterArts forms part of the international research network known as the AUMI Consortium. KU-AUMI InterArts has been tasked by the Consortium to focus specifically on interdisciplinary arts and improvisation, which led to the organization’s commitment to community-building “across abilities through creativity.” As KU-AUMI InterArts member and KU professor Nicole Hodges Persley expressed in conversation:

KU-AUMI InterArts seeks to decentralize hierarchies of ability by facilitating events that reveal the limitations of able-bodiedness as a concept altogether. An approach that does not challenge the able-bodied/disabled binary could dangerously contribute to the infantilizing and marginalization of certain bodies over others. Therefore, we must remain invested in understanding that there are scales of mobility that transcend our binary renditions of embodiment and we must continue to question how it is that we account for equality across abilities in our Lawrence community.

Local and international attempts to interpret the AUMI as a technology for the development of radical, improvisational methods are by no means a departure from its creators’ motivations. In line with KU-AUMI InterArts and the AUMI Consortium, my work here is that of naming how communal, mixed-ability interactions in Lawrence have come to disrupt the otherwise ableist communication methods that dominate musical production and performance.

The AUMI is designed to be accessed by those with profound physical disabilities. The AUMI software works using a visual tracking system, represented on-screen with a tiny red dot that begins at the very center. Performers can move the dot’s placement to determine which part of their body and its movement the AUMI should translate into sound. As one moves, so does the dot, and, in effect, the selected sound is produced through the performer’s movement.

Could this curious technology help build radical new coalitions between researchers and disabled populations? Mara Mills’s research examines how the history of communication technology in the United States has advanced through experimentation with disabled populations that have often been positioned as an exemplary pretext for funding, but then they are unable to access the final product, and sometimes even entirely erased from the history of a product’s development in the name of universal communication and capitalist accumulation. Therefore, the AUMI’s usage beyond the disabled populations first involved in its invention always stands on dubious historical, political, and philosophical ground. Yet, there is no doubt that the AUMI’s challenge to ableist musical production and performance has unexpectedly affected and reshaped communication for performers of different abilities in the Lawrence jam sessions, which speaks to its impressive coalitional potential. Institutional (especially academic) research invested in the AUMI’s potential then ought to, as its perpetual point of departure, loop back its energies in the service of disabled populations marginalized by ableist musical production and communication.

Facilitators of the library jam sessions, including myself, deliberately avoid exoticizing the AUMI and separating its initial developers and users from its present incarnations. To market the AUMI primarily as a peculiar or fringe musical experience would unnecessarily “Other” both the technology and its users. Instead, we have emphasized the communal practices that, for us, have made the AUMI work as a radically accessible, inclusionary, and democratic social technology. We are mainly invested in how the AUMI invites us to reframe the improvisational aspects of human communication upon a technology that always disorients and reorients what is being shared, how it is being shared, and the relationships between everyone performing. Disorientations reorient when it comes to our Lawrence AUMI community, because a tradition is being co-created around the transformative potential of the AUMI’s response-rate latency and its sporadic visual mode of recognition.

In his work on the AUMI, KU alumni and sound studies scholar Pete Williams explains how the wide range of mobility typically encouraged in what he calls “standard practice” across theatre, music, and dance is challenged by the AUMI’s tendency to inspire “smaller” movements from performers. While he sees in this affective/physical shift the opportunity for able-bodied performers to encounter “…an embodied understanding of the experience of someone with limited mobility,” my work here focuses less on the software’s potential for able-bodied performers to empathize with “limited” mobility and more on the atypical forms of social interaction and communication the AUMI seems to evoke in mixed-ability settings. An attempt to frame this technology as a disability simulator not only demarcates a troubling departure from its original, intended use by children with severe physical disabilities, but also constitutes a prioritization of able-bodied curiosity that contradicts what I’ve witnessed during mixed-ability AUMI jam sessions in Lawrence.

Sure, some able-bodied performers may come to describe such an experience of simulated “limited” mobility as meaningful, but how we integrate this dynamic into our analyses of the AUMI matters, through and through. What I aim to imply in my read of this technology is that there is no “limited” mobility to experientially empathize with in the first place. If we hold the AUMI’s early history close, then the AUMI is, first and foremost, designed to facilitate musical access for performers with severe physical disabilities. Its structural schematic and even its response-rate latency and sporadic visual mode of recognition ought to be treated as enabling functions rather than limiting ones. From this position, nothing about the AUMI exists for the recreation of disability for able-bodied performers. It is only from this specific position that the collectively disorienting/reorienting modes of communication enabled by the AUMI among mixed-ability groups may be read as resisting the violent history of labor exploitation, erasure, and appropriation Mills warns us about: that is, when AUMI initiatives, no matter how benevolently universal in their reach, act fundamentally as a strategy for the efficacious and responsible unsettling of ableist binaries.

The way the AUMI latches on to unexpected parts of a performer’s body and the “discrepancies” of its body-to-sound response rate are at the core of what sets this technology apart from many other instruments, but it is not the mechanical features alone that accomplish this. Sure, we can find similar dynamics in electronics of all sorts that are “failing,” in one way or another, to respond with accuracies intended during regular use, or we can emulate similar latencies within most recording software available today. But what I contend sets the AUMI apart goes beyond its clever camera-based visual tracking system and the sheer presence of said “incoherencies” in visual recognition and response rate.

Image by Ray Mizumura-Pence at The Commons, Spooner Hall, KU, at rehearsals for “(Un)Rolling the Boulder: Improvising New Communities” performance in October 2013.

What makes the AUMI a unique improvisational instrument is the tradition currently being co-created around its mechanisms in the Lawrence area, and the way these practices disrupt the borders between able-bodied and disabled musical production, participation, and communication. The most important component of our Lawrence-area AUMI culture is how facilitators engage the instrument’s “discrepancies” as regular functions of the technology and as mechanical dynamics worthy of celebration. At every AUMI library jam session I have participated in, not once have I heard Tucker or other facilitators make announcements about a future “fix” for these functions. Rather, I have witnessed an embrace of these features as intentionally integrated aspects of the AUMI. It comes as no surprise, then, that a “Battle of the Bands” event was organized as a way of leaning even further into what makes the AUMI more than a radically accessible musical instrument––that is, its relationship to orientation.

Perhaps it was the competitive framing of the event––we offered small prizes to every participating band––or the diversity among that day’s participants, or even the numerous times some of the performers had previously used this technology, but our event evoked a deliberate and collaborative improvisational method unfold in preparation for the performances. An ensemble mentality began to congeal even before performers entered the studio space, when Tucker first encouraged performers to choose their own fellow band members and come up with a working band name. The two newly-formed bands––Jayhawk Band and The Human Pianos––took turns, laying down collaboratively premeditated improvisations with composition (and perhaps even prizes) in mind. iPad AUMIs were installed in a circle on stands, with studio monitor headphones available for each performer.

Jayhawk Band’s eponymous improvisation “Jayhawks,” which brings together stylized steel drums, synthesizers, an 80’s-sounding floor tom, and a plucked woodblock sound, exemplifies this collaborative sensory ethos, unique in the seemingly discontinuous melding of its various sections and the play between its mercurial tessellations and amalgamations:

In “Jayhawks,” the floor tom riffs are set along a rhythmic trajectory defiant of any recognizable time signature, and the player switches suddenly to a wood block/plucking instrument mid-song (00:49). The composition’s lower-pitched instrument, sounding a bit like an electronic bass clarinet, opens the piece and, starting at 00:11, repeats a melodically ascending progression also uninhibited by the temporal strictures of time signature. In fact, all the melodic layers in “Jayhawk,” demonstrate a kind of temporally “unhinged” ensemble dynamic present in most of the library jam sessions that I’ve witnessed. Yet unexpected moves and elements ultimately cohere for jam session performers, such as Jayhawk Band’s members, because certain general directions were agreed upon prior to hitting “record,” whether this entails sound bank selections or compositional structure. All that to say that collective formalities are certainly at play here, despite the song’s fluid temporal/melodic nuances suggesting otherwise.

Five months after the battle of the bands, The Human Pianos and Jayhawk Band reunited at the library for a jam session. This time, performers were given the opportunity to prepare their individual iPad setup prior to entering the studio space. These customized setup selections were then transferred to the iPads inside the studio, where the new supergroup recorded their notoriously polyrhythmic, interspecies, sax-riddled composition “Animal Parade”:

As heard throughout the fascinating and unexpected moments of “Animal Parade,” the AUMI’s sensitivity can be adjusted for even the most minimal physical exertion and its sound bank variety spans from orchestral instruments, animal sounds, synthesizers, to various percussive instruments, dynamic adjustments, and even prefabricated loops. Yet, no matter how familiar a traditionally trained (and often able-bodied) musician may be with their sound selection, the concepts of rhythmic precision and musical proficiency––as they are understood within dominant understandings of time and consistency––are thoroughly scrambled by the visual tracking system’s sporadic mode of recognition and its inherent latency. As described above, it is structurally guaranteed that the AUMI’s red dot will not remain in its original place during a performance, but instead, latch onto unexpected parts of the body.

Simultaneously, the dot-to-movement response rate is not immediate. My own involvement with “the unexpected” in communal musical production and performance moulds my interpretation of what is socially (and politically) at work in both “Jayhawks” and “Animal Parade.” While participating in AUMI jam sessions I could not help but reminisce on similar experiences with the collective management of orientations/disorientations that, while depending on quite different technological structures, produced similar effects regarding performer communication.

Being a researcher steeped in the L.A. area Salsa, Latin Jazz, and Black Gospel scenes meant that I was immediately drawn to the AUMI’s most disorienting-yet-reorienting qualities. In Timba, the form of contemporary Afrocuban music that I most closely studied back in Los Angeles, disorientations and reorientations are the most prized structural moments in any composition. For example, Issac Delgado’s ensemble 1997 performance of “No Me Mires a Los Ojos” (“Don’t Look at Me In the Eyes”)– featuring now-legendary performances by Ivan “Melon” Lewis (keyboard), Alain Pérez (bass), and Andrés Cuayo (timbales)—sonically reveals the tradition’s call to disorient and reorient performers and dancers alike through collaborative improvisations:

Video Filmed by Michael Croy.

“No Me Mires a los Ojos” is riddled with moments of improvisational coalition formed rather immediately and then resolved in a return to the song’s basic structure. For listeners disciplined by Western musical training, the piece may seem to traverse several time signatures, even though it is written entirely in 4/4 time signature. Timba accomplishes an intense, percussively demanding, melodically multifaceted set of improvisations that happen all at once, with the end goal of making people dance, nodding at the principle tradition it draws its elements from: Afrocuban Rumba. Every performer that is not a horn player or a vocalist is articulating patterns specific to their instrument, played in the form of basic rhythms expected at certain sections. These patterns and their variations evolved from similar Rumba drum and bell formats and the improvisational contributions each musician is expected to integrate into their basic pattern too comes from Rumba’s long-standing tradition of formalized improvisation. The formal and the improvisational function as single communicative practice in Timba. Performers recall format from their embodied knowledge of Rumba and other pertinent influences while disrupting, animating, and transforming pre-written compositions with constant layers of improvisation.

What ultimately interests me the most about the formal registers within the improvisational tradition that is Timba, is that these seem to function, on at least one level, as premeditated terms for communal engagement. This kind of communication enables a social set of interactions that, like Jazz, grants every performer the opportunity to improvise at will, insofar as the terms of engagement are seriously considered. As with the AUMI library jam sessions, timba’s disorientations, too, seem to reorient. What is different, though, is how the AUMI’s sound bank acts in tandem with a performer’s own embodied musical knowledge as an extension of the archive available for improvisation. In Timba, the sound bank and knowledge of form are both entirely embodied, with synthesizers being the only exception.

Timba ensembles and their interpretations of traditional and non-Cuban forms, like the AUMI and its sound bank, use reliable and predictable knowledge bases to break with dominant notions of time and its coherence, only to wrangle performers back to whatever terms of communal engagement were previously decided upon. In this sense, I read the AUMI not as a solitary instrument but as a partial orchestration of sorts, with functions that enable not only an accessible musical experience but also social arrangements that rely deeply on a more responsible management of the unexpected. While the Timba ensemble is required to collaboratively instantiate the potential for disorientations, the AUMI provides an effective and generative incorporation of said potential as a default mechanism of instrumentation itself.

Image from “How do you AUMI?” at the Lawrence Public Library

As the AUMI continues on its early trajectory as a free, downloadable software designed to be accessed by performers of mixed abilities, it behooves us to listen deeply to the lessons learned by orchestral traditions older than our own. Timba does not come without its own problems of social inequity––it is often a “boy’s club,” for one––but there is much to learn about how the traditions built around its instruments have managed to centralize the value of unexpected, multilayered, and even complexly simultaneous patterns of communication. There is also something to be said about the necessity of studying the improvisational communication patterns of musical traditions that have not yet been institutionalized or misappropriated within “first world” societies. Timba teaches us that the conga alone will not speak without the support of a community that celebrates difference, the nuances of its organization, and the call to return to difference. It teaches us, in other words, to see the constant need for difference and its reorganization as a singular practice.

The work started with the AUMI’s earliest users in Poughkeepsie, New York and that involving mixed-ability ensembles in Lawrence, Kansas today is connected through the AUMI Consortium’s commitment to a kind of research aimed at listening closely and deeply to the AUMI’s improvisational potential interdisciplinarily and undisciplinarily across various sites. A tech innovation alone will not sustain the work of disrupting the longstanding, rooted forms of ableism ever-present in dominant musical production, performance, and communication, but mixed-ability performer coalitions organized around a radical interrogation of coherence and expectation may have a fighting chance. I hope the technology team never succeeds at working out all of the “discrepancies,” as these are helping us to build traditions that frame the AUMI’s mechanical propensity towards disorientation as the raw core of its democratic potential.

—

Featured Image: by Ray Mizumura-Pence at The Commons, Spooner Hall, KU, at rehearsals for “(Un)Rolling the Boulder: Improvising New Communities” performance in October 2013.

—

Caleb Lázaro Moreno is a doctoral student in the Department of American Studies at the University of Kansas. He was born in Trujillo, Peru and grew up in the Los Angeles area. Lázaro Moreno is currently writing about methodological designs for “the unexpected,” contributing thought and praxis that redistributes agency, narrative development, and social relations within academic research. He is also a multi-instrumentalist, composer, and producer, check out his Soundcloud.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Introduction to Sound, Ability, and Emergence Forum –Airek Beauchamp

Unlearning Black Sound in Black Artistry: Examining the Quiet in Solange’s A Seat At the Table — Kimberly Williams

Experiments in Agent-based Sonic Composition — Andreas Duus Pape

Recent Comments