Into the Woods: A Brief History of Wood Paneling on Synthesizers*

*a companion piece of this research, on electronic sounds as lively individuals, is forthcoming in the American Quarterly special issue on sound, September 2011.

Not long ago, while researching the history of synthesized sound—or taking a break to troll for interesting synthesizers for sale online (activities that, for me, inevitably blend together)—I came across a thriving industry of small companies that offer custom-made wood panels to adorn the sides of old and new synths, like Synthwood, Custom Synths, Analogics, and MPCStuff.

As Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco note in Analog Days, their history of Moog synthesizers, an “analog revival” is underway: “Today in the digital world, there is a longing to get back to what was lost” (9). The music technology magazine Sound on Sound concurs, documenting a renewed interest among electronic music-makers in modular synthesizers like those popularized by Moog and others in the late-1960s. Yet there seems to be more at play with this proliferation of wood customizations than merely nostalgia for analog synths, Hammond organs, and hi-fi cabinetry. How might we interpret this desire to adorn—lovingly, even obsessively—steel-encased machines that produce sound by electronic means, with various species of wood? What does this realm of audio esoterica reveal about material and social aspects of musical instruments, and the workings of contemporary media cultures more broadly?

On Contingency and Faith: Walnut, Purple Felt, and the True Cross

Pinch and Trocco describe the Minimoog as the first synthesizer to become a “classic,” due to its relative ease of use, widespread availability, portability and compact design (214). In the retrospective imaginations of historians and musicians, a significant feature that established its classic design was the walnut wood case on an early generation of Minimoog models.

However, Bill Hemsath, an engineer who assembled the first Minimoog prototypes in 1969-70, told Pinch and Trocco that these instruments were assembled from “junk I found in the attic” and an assortment of affordable materials cobbled together in the moment (214). Jim Scott, another engineer who worked on developing the Minimoogs, explained in a 1997 interview: “the reason we made it walnut [was] because Moog had gotten a deal someplace and had a whole barnful.” He noted that “the musicians certainly appreciated the fact that it was made out of walnut,” but eventually the designers “ran out of walnut and started buying something else and slapping paint on it to make it look like walnut.” The various kinds of wood used on models from different years, and the exact start and end dates of the coveted walnut models, remain contested matters among Moog enthusiasts.

Hemsath elaborated on this history in a 1998 interview by making an analogy to “classic” piano design: “There’s a similar story from Steinway. Back when they first got started in the U.S. they used to buy their felts from a feltmaker in Paris… And they got a lot of purple felt because [the supplier] used to be the felt maker for Napoleon’s army, and had a lot left over. So the colored cores in the hammers of those old Steinways were purple because of Napoleon’s army. Well, [the supplier] ran out, and [Steinway] said, red’s fine. They started making pianos with red felt, which is what they have today, and people started complaining, saying, it’s not a real Steinway, it’s not purple.” Like the proverbial purple felt on original Steinway pianos, walnut panels on synthesizers became “classic” because of their association with an originary moment, however happenstance, in the history of a particular instrument, and a limited supply and production run that rendered the material in question relatively rare.

So, a contemporary synthesizer enthusiast’s desire to acquire a “classic” walnut Minimoog, or to commemorate its aesthetic with customized wood panels, is in part an effort to establish a material connection to history. Synthesizer history unfolds in the deep time of technoscience which, as Donna Haraway has argued, often “barely secularize[s]” Judeo-Christian narratives of first and last things, of figural anticipation and fulfillment (9-10). The concern among some synthesizer enthusiasts to possess either the actual wood of an early-model Minimoog, or a faithful substitute for it, indeed resonates with Christian material cultures around relics of the True Cross and next-best artifacts with suitable provenance. A historical conjuncture that is contingent on otherwise unremarkable circumstances (e.g., Bob Moog’s good deal on a barnful of walnut in upstate New York) is marked as an originary or otherwise defining moment (the “invention” of a “classic” synthesizer) for a culture that defines itself as proceeding from it; the former is made to anticipate the latter, and the latter comes to fulfill the former.

Taking Stock: Materialities of Instruments, Sounds, Ecosystems

What kind of wood panels live in my studio? The manual to my Jomox XBase 09 drum machine, from 1999, details that its “steel sheet body” is bookended by “varnished side panels made of alder wood.” Wikipedia‘s pop-anthropological roundup of alder’s “use by humans” includes smoking various foods, treating skin inflammations and tumors, and building electric guitars. Fender Stratocasters have been built with alder since the 1950s. Guitar enthusiasts are notoriously fussy about which type of wood comprises the instrument’s body because of its effect on tone. Scientists, meanwhile, have taken to applying medical imaging techniques to Stradivarius violins, trying to “crack the mystery” of its prized tone. (Some say it’s due to the particular density of slow-growing trees in the Little Ice Age; others conclude it must be the varnish.)

Given these interconnected concerns with instrument materials and the composition of tone, one might venture an etymological connection between timbre—which the Oxford English Dictionary describes as the character or quality of a musical sound depending upon the instrument producing it—and timber, which references “the matter or substance of which anything is built up or composed.” Music scholars often characterize timbre as the materiality of sound. Despite longstanding knowledge of the relationships of timber and timbre among instrument builders and musicians, and possible overlaps in historical applications of these words, placing wood panels on the sides of synthesizers surely has no effect on the resulting tone. Or does it? Audiophiles are prone toward occult-like habits, such as placing a single coin on top of a speaker to absorb vibration; and wood panels may well have subtle effects on the overall stability of an electronic instrument, resulting in barely perceptible sonic artifacts.

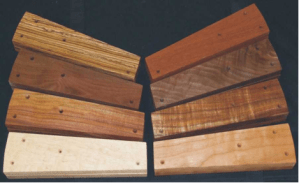

My Virus B synthesizer from the late-1990s has darker wood side panels than the Jomox, sort of a faux mahogany. Recently I wrote to Access Music, explaining my research on synthesizer history and inquiring what kind of wood they used. They replied that the B series featured stained beech wood (also commonly used and appreciated for producing smoked German beers and cheeses). Virus volunteered that they “in general do not use any kind of tropical wood for our devices.” Using sustainable wood has become a mandate and marketing concern at the Moog company as well; Moog’s wood “comes primarily from Tennessee. Hardwoods in Tennessee are growing faster than they are being harvested… US hardwoods are a world-wide model of sustained forest management.” Among contemporary synthesizer companies, there is often a selective eco-consciousness; as synthesizer designer Jessica Rylan suggested in our interview for Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound (Duke: 2010), it is arguably impossible to build a synthesizer that does not incorporate at least some materials that are toxic in stages of manufacturing and/or disposal.

The paradox of dressing up an electronic machine made partly of toxic materials and processes with a sustainable-wood exterior is a fitting metaphor—like a contemporary fig leaf—for how we outwardly express environmentalist concern, despite plenty of contradictions in practice. Wood-adorned electronic devices, in all their glorious contradictions, are especially resonant in this cultural moment; see Asus’s EcoBook, Karvt’s lineup of custom wood skins for MacBooks, and, my favorite, Flashsticks: handmade wood USB “sticks” that combine “the high tech world of computing with the simplicity of the world of nature.” The story of Flashsticks’ handmade creation is a case study in eco-contradiction: the website implies that no trees were harmed in the making of their USB sticks—the company uses locally-sourced, “fallen wood from the previous winter’s storms”—yet we do not hear of the toxic materials that may comprise the drive itself.

Wood panels indeed work to conceal inconvenient truths. As Ruth Schwartz Cowan pointed out, the midcentury aesthetic of hiding household appliances behind wood paneling typified a culture that concealed gendered divisions of domestic labor (205). Lisa Parks has documented the similar recent phenomenon of dressing up cell towers as trees, which obscures the politics of media infrastructure behind a cloak of “nature.”

This is also a story about the mirage of a space between nature and artifice. Retro-culture enthusiasts celebrate that “real cars have fake wood paneling.” Meanwhile, a company called iBackwoods has engineered a “real wood” iPhone case that pays tribute to “timeless style of a wood panel station wagon.” Moog’s new Filtatron application for iPad, a software emulation of the company’s Moogerfooger filter pedal, is rendered authentic by its virtual wood panels. All of these examples reveal the “nature” of wood paneling to be cultural all the way down.

Washington DC - National Museum of American History: America on the Move - Park Forest, Illinois 1950s by Wallyg (via Flickr)

Ultimately, wood paneling might prompt us to recognize the interconnectedness among seemingly divergent materials, environments, and social practices. Consider, as a useful comparison to the climate-forged Stradivarius, the ash baseball bat: cherished by players for its “magical” effects on hitting, and now threatened by a warming climate and killer beetle in its source forests in Pennsylvania. Every synthesizer likewise holds and explodes into an ecosystem, and sometimes sounds like one too. The composer Mira Calix has suggested that analog synthesizers, with their individual quirks that increase with age, are much like wooden instruments; both seem to breathe like “little creatures” and take on a unique character, like a human voice. Our synthesizers, our kin.

Bob Seger, Champion of Misfits

Bob Seger and the sort of classic rock he performs, embodies and represents, for me (and apparently many others), the relentlessly uncool. Youth, drugs and nonconformity have long been my standards of “rock,” and within this triad, Bob Seger’s formal, cinematic songs, have always come across as a little tired. Osvaldo Oyola wrote specifically last week about these foibles: the stilted piano and canned Chuck Berry riffs sound more like parody than gospel, while the parade of effects on Seger’s voice, also quite derivative, could have also fit on a Bruce Springsteen album (although you could replace the influence of Chuck Berry with that of the quintessentially less cool Phil Spector). Problematically, even though I loathe Seger’s catalog, I love Springsteen’s, this of course has made for some very popular conversations at the bar. In fact, it was last July at a local New Brunswick haunt that I had this conversation last. My friend, who will remain nameless, completely disagreed: Seger was cool, I just couldn’t hear it, in fact I had to see it to believe it.

Bob Seger and the sort of classic rock he performs, embodies and represents, for me (and apparently many others), the relentlessly uncool. Youth, drugs and nonconformity have long been my standards of “rock,” and within this triad, Bob Seger’s formal, cinematic songs, have always come across as a little tired. Osvaldo Oyola wrote specifically last week about these foibles: the stilted piano and canned Chuck Berry riffs sound more like parody than gospel, while the parade of effects on Seger’s voice, also quite derivative, could have also fit on a Bruce Springsteen album (although you could replace the influence of Chuck Berry with that of the quintessentially less cool Phil Spector). Problematically, even though I loathe Seger’s catalog, I love Springsteen’s, this of course has made for some very popular conversations at the bar. In fact, it was last July at a local New Brunswick haunt that I had this conversation last. My friend, who will remain nameless, completely disagreed: Seger was cool, I just couldn’t hear it, in fact I had to see it to believe it.

In order to understand Bob Seger, I needed to watch Mask, a 1985 retelling of The Elephant Man starring Eric Stoltz as the deformed Rocky Dennis and Cher as his mother Rusty Dennis. Mask was released two years after Risky Business, and featured a number of Bob Seger songs predominantly in the soundtrack. These songs uniformly mixed to the foreground, often serving as Rocky’s theme, juxtaposed against an ambient soundtrack of songs by black musicians like Little Richard and Gary US Bonds. These black oldies, “Tutti Frutti” and “Quarter to Three,” are used thematically when Rusty’s friends, a bunch of guys in a motorcycle gang, are partying. Not only is Rocky othered from the kids at school because he is ugly, he is poor, raised by a single mother with a drug addiction. Although whiteness takes center stage in this film, it holds a complex relationship to blackness. Rocky and Rusty are atypically white, finding community only with each other and a super-masculine network of bikers; they are misfits, doing their best to pass in a mainstream and affluent white society.

Bob Seger’s “Katmandu,” is the song which introduces Rocky in the opening credits. It is guilty of the trademark Bob Seger whiteness: more refurbished Chuck Berry and piano so droll it could have been played by a metronome. In the context of Rocky and his struggle to identify with white society however, it paints Seger in a different light. Bob Seger’s uncoolness can be read as a failed attempt to pay homage to black musicians like the aforementioned Little Richard and Gary US Bonds. Instead of suggesting a totalizing narrative of white appropriation, I argue that Bob Seger can be understood as a musician who would never be completely accepted by his heroes or critics. Reflected in the posters on Rocky’s wall and Universal’s contract negotiations with Columbia Records (Bruce Springsteen had been first choice for the soundtrack), Seger was not even cool to the director of the film, Peter Bogdanovich, who refered to his music as “inappropriate.”

Toward the end of the movie, Rocky holds his blind girlfriend for the last time. Her parents, disgusted by his face (but probably also by his shabby clothing), keep the two separate. Contradicting the escape narrative of Springsteen’s “Born to Run,” Rocky evinces the power of fantasy toward coping with discrimination: “We can’t run away Diana. But we can sort of run away in our minds. We can remember camp, the mountains and the Ocean…especially New Year’s Eve” (Mask Part 11 4:40). Like Rocky, Seger can’t run away from his whiteness, even though he may not relate to it, or fully embrace it, it is ever present in his recordings. Songs like “Old Time Rock and Roll,” “Katmandu,” and even “Night Moves” are celebrations of music as a forum of imagination – one where identity, be it black or white, can be reimagined as something else. Though “Old Time Rock and Roll,” will sound forever white, it relates the experience of otherness. Try as he might, Seger has no idea how to sound authentically black, and this is evident through both its celebratory lyrics and contrived arrangement.

Growing up in a bi-racial household, where, depending on the holiday, my Jewishness could be as visible as my blackness, I feel a strong kinship to figures like Rocky, not completely belonging to any ethnic community. Perhaps this led to a juvenile obsession with Springsteen, who, according to my father, everyone could relate to, regardless of color (he worked at an all-night Jersey Shore diner, the Inkwell, in the early 1970s). Bruce though, was never really misfit, mulatto or poor; whether discussing his working class freehold roots, or his first guitar, his music epitomizes white privilege. Even his stage shows feature Clarence Clemons, The Big (Black) Man, notably subordinate to Bruce, or “The Boss.” Although now, my Bruce phase seems laughable, I wonder if it was also a fantasy of fitting in, of recovering a fantastic and invisible whiteness deep within myself. When he wrote “Old Time Rock and Roll,” was Bob Seger trying to do the same and recover a font of blackness deep within himself? I now see a complex web of identity politics informed by an economic and social history of Rock and Roll, but this holds an uneasy and complex relationship with the part of me that still believes in rock and roll. I was, am, and forever will be the misfit who found an identity in the church of rock and roll. Though the sermons have changed, in high school, Springsteen was the pastor, and I suspect that for my friend at the bar, Seger also conducted service. Even though I could never completely fit in to the rich white world of these artists, I wonder if this speaks to a fundamental affinity. Did Springsteen and Seger ever feel like outcasts, later to find solace in the black cool of Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino? In the context of these figures and their music, how could whiteness seem anything but contrived, misfit and ugly – or in truth, is this dialectic really the beat which pushes rock and roll forward?

Growing up in a bi-racial household, where, depending on the holiday, my Jewishness could be as visible as my blackness, I feel a strong kinship to figures like Rocky, not completely belonging to any ethnic community. Perhaps this led to a juvenile obsession with Springsteen, who, according to my father, everyone could relate to, regardless of color (he worked at an all-night Jersey Shore diner, the Inkwell, in the early 1970s). Bruce though, was never really misfit, mulatto or poor; whether discussing his working class freehold roots, or his first guitar, his music epitomizes white privilege. Even his stage shows feature Clarence Clemons, The Big (Black) Man, notably subordinate to Bruce, or “The Boss.” Although now, my Bruce phase seems laughable, I wonder if it was also a fantasy of fitting in, of recovering a fantastic and invisible whiteness deep within myself. When he wrote “Old Time Rock and Roll,” was Bob Seger trying to do the same and recover a font of blackness deep within himself? I now see a complex web of identity politics informed by an economic and social history of Rock and Roll, but this holds an uneasy and complex relationship with the part of me that still believes in rock and roll. I was, am, and forever will be the misfit who found an identity in the church of rock and roll. Though the sermons have changed, in high school, Springsteen was the pastor, and I suspect that for my friend at the bar, Seger also conducted service. Even though I could never completely fit in to the rich white world of these artists, I wonder if this speaks to a fundamental affinity. Did Springsteen and Seger ever feel like outcasts, later to find solace in the black cool of Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino? In the context of these figures and their music, how could whiteness seem anything but contrived, misfit and ugly – or in truth, is this dialectic really the beat which pushes rock and roll forward?

AT

Recent Comments