Benefit Concerts and the Sound of Self-Care in Pop Music

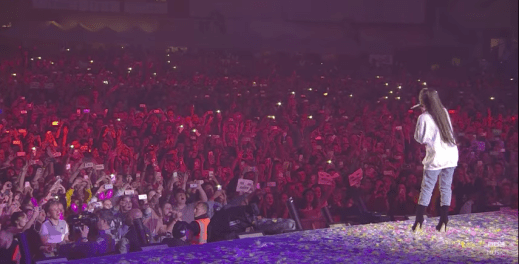

Less than two weeks after a suicide bombing killed 22 people at the Manchester Arena following an Ariana Grande concert, the singer was back on stage in the city. She capped her three-hour One Love Manchester benefit concert with the 2015 single, “One Last Time,” which had found its way back into the UK Singles chart in the days following the blast. It was technically a solo performance, but Grande was joined on stage by the many artists who had already held the mic that day. At one point she was too overwhelmed to sing, and the audience took over for her. Grande’s occasional loss of voice is moving to watch. Throughout the concert, she would frequently struggle to speak, mostly sticking to short introductions of singers and a variation of “Thanks for being here; I love you so much,” her voice often cracking or sounding uncharacteristically pinched, the tears barely held at bay. Until “One Last Time,” she could always find her full voice through song, but as dusk settled on the city and the concert drew to a close, Grande could no longer sing through the weight of the moment, so the community she’d called together so she could “see and hold and uplift” them lifted her.

Benefit concerts and the products surrounding them—as well as the critiques that target them—have become familiar fare since the 1984 Band Aid recording of “Do They Know It’s Christmas” spun off to form 1985’s Live Aid, a multi-site concert event complete with commemorative souvenirs and the performance of the USA For Africa single, “We Are the World.” Skeptical accounts of benefit concerts fall like crumbs from Marx’s beard: they’re capitalism deployed as band-aids on problems capitalism created; they’re opportunities for celebrities to enhance their brands; they’re colonial; they’re neo-colonial; they’re exaggerated performances of wokeness intended to absolve people of their complicity in systems of violence. As communal rituals in response to tragedy, though, benefit concerts also function as metaphorical keystones that hold the tension of competing emotions, politics, and sounds. Listening to music emerges as a form of self-care, but that act may not sound the same for different people. Looking at the case of Grande’s One Love Manchester, I will map self care in the context of this contemporary moment by filtering the Manchester concert through Cheryl Lousley’s feminist analysis of benefit concerts (2014). Specifically, in order to highlight what’s different about One Love Manchester, I’ll start with Lousley’s attention to the way feminized compassion is performed through benefit concerts as an outward-facing love. Here, Grande performs the same kind of feminized compassion but shifts the focus of the benefit to an inward self-care. But not all selves experience care or self-care the same way. I’ll end by listening to Grande’s “One Last Time” alongside Solange Knowles’s “Borderline” (2016) in an effort to situate those sounds in contemporary politics that shape who has access to what kind of care.

Cheryl Lousley, in “With Love from Band Aid: Sentimental Exchange, Affective Economies, and Popular Globalism,” grants that benefit concerts aren’t just about fake feeling, but she doesn’t lose sight of capitalist and imperialist critiques. For her, benefit concerts are events “where feeling is validated, where space is made for feeling.” For her, if we allow that participants (whether organizers, performers, audiences) can be aware of the capitalism-fueled problems of benefit concerts but choose to be involved with them anyway, then we can access further dimensions of cultural analysis. In Lousley’s case, that includes gender and emotion, as she keys in on how the performance of feminized compassion and love creates an “affective economy” of “feeling too much.” When confronted with tragedy enormous enough to press the limits of the social imaginary, society looks for somewhere to put their big feelings and turn them into some kind of action. Benefit concerts like Live Aid invoke a moral imperative to give of one’s own wealth to someone who needs it, a public moral activism Lousley grounds in feminized emotional labor, a gendered compassion that extends to the entire nation. She demonstrates that public Anglophone discourse surrounding the Ethiopian famine leading up to Live Aid revolved around domestic scenes of feminized affect performed across gender boundaries. The affect of Live Aid, then, included a gendered performance of love and compassion turned outward, and this has been the template for numerous benefit concerts since, including Farm Aid (1985), Concert for New York City (2001), and Hope for Haiti Now (2010), among others.

The announcement of Ariana Grande’s One Love Manchester echoes Lousley’s idea of the benefit concert as a gendered performance of love and compassion. A skim of her Twitter post (which is a picture of a message longer than 140 characters) announcing the event reveals emotive terms and phrases throughout. Grande offers sympathy, compassion, admiration, solidarity, and, importantly, music, the latter in the form of a concert where she and her fans can feel too much together. What’s different about Grande’s benefit concert, though, is that it’s pitched not as an outward demonstration of compassion for others, but as an inward compassion for one’s self, what I call here “self-care”:

The announcement of Ariana Grande’s One Love Manchester echoes Lousley’s idea of the benefit concert as a gendered performance of love and compassion. A skim of her Twitter post (which is a picture of a message longer than 140 characters) announcing the event reveals emotive terms and phrases throughout. Grande offers sympathy, compassion, admiration, solidarity, and, importantly, music, the latter in the form of a concert where she and her fans can feel too much together. What’s different about Grande’s benefit concert, though, is that it’s pitched not as an outward demonstration of compassion for others, but as an inward compassion for one’s self, what I call here “self-care”:

From the day we started putting the Dangerous Woman tour together, I said that this show, more than anything else, was intended to be a safe space for my fans. A place for them to escape, to celebrate, to heal, to feel safe and to be themselves…[The bombing] will not change that.

At the concert we can hear Grande model self-care for her audience as she struggles to maintain her composure and then gathers it through song, performing for herself the same kind of care she wants concert attendees to extend to themselves and their city.

Analyses and critiques of self-care generally start with Audre Lorde’s A Burst of Light quote, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare,” then contextualize how this quote functions for Lorde, a queer woman of color, differently than it does for the white women who have become the faces and consumers of #selfcare. Caring for one’s self when the world wishes to marginalize and destroy you is, indeed, warfare. And while white women suffer at the hands of the patriarchy, the long history of feminist movements also reveals that white women not only have access to privilege and resources unavailable to women of color, but also that they have wielded that privilege in ways that further marginalize and harm women of color. In other words, self-care means something different based on who the self is and—and Sara Ahmed has outlined this in characteristically brilliant terms—who else will show up to care for you. Intersectionality shows us that queer people and women of color and people with disabilities often must perform self-care because the world is not organized to care for them. “For those who have to insist they matter to matter,” Ahmed writes, “self-care is warfare,” a necessity for survival. What I want to explore below is how self-care can sound different based on who the self is and whether that self must “insist they matter to matter.”

Ariana Grande’s performance of “One Last Time” at One Love Manchester presents self-care for a self who also receives support from others. Here, Grande mirrors the collaborative nature of Live Aid by performing alongside other pop stars whose presence—confirmed relatively last-minute, almost certainly with a degree of effort to rearrange busy schedules, and without the usual compensation for their performance—tells Manchester and those harmed by the bombing that they matter. For “One Last Time,” many voices join together to provide “a safe space for [Grande’s] fans” to take care of themselves, and they, in turn, are able to take care of Grande when her voice escapes her. The underlying theme of many critiques of white feminist self-care is that it is frivolous, a market-driven excuse to indulge, a selfish pursuit of happiness for happiness’s sake. And sure, as with benefit concerts, capitalism is a big problem here, and sometimes we call something self-care when it really is just self-indulgence. But I’d like to suggest we can make a finer distinction that doesn’t require the oversimplification that comes with divvying up some actions or products as care and others as indulgence (or: Schick’s self-care marketing of a razor may be exploitative at the very same time the razor actually functions as a form of self-care for some), and this is one reason I find the One Love Manchester concert compelling. Manchester and the survivors of the blast and Ariana Grande and her touring team could absolutely use the safe space the concert is trying to create. As Lousley reminds us, the performed compassion of benefits isn’t simply fake feeling; the trauma Grande and the city and her fans experienced was real, and it’s especially audible in the moments Grande’s voice is pinched off mid-lyric. Let’s consider others who could use the safe space One Love Manchester is trying to create: victims of bombings and terror throughout the world. The music industry isn’t as eager to remind them that they matter. Self-care, it turns out, is easier for some to perform because the world is literally willing to invest in the care of those selves.

Ariana Grande’s performance of “One Last Time” at One Love Manchester presents self-care for a self who also receives support from others. Here, Grande mirrors the collaborative nature of Live Aid by performing alongside other pop stars whose presence—confirmed relatively last-minute, almost certainly with a degree of effort to rearrange busy schedules, and without the usual compensation for their performance—tells Manchester and those harmed by the bombing that they matter. For “One Last Time,” many voices join together to provide “a safe space for [Grande’s] fans” to take care of themselves, and they, in turn, are able to take care of Grande when her voice escapes her. The underlying theme of many critiques of white feminist self-care is that it is frivolous, a market-driven excuse to indulge, a selfish pursuit of happiness for happiness’s sake. And sure, as with benefit concerts, capitalism is a big problem here, and sometimes we call something self-care when it really is just self-indulgence. But I’d like to suggest we can make a finer distinction that doesn’t require the oversimplification that comes with divvying up some actions or products as care and others as indulgence (or: Schick’s self-care marketing of a razor may be exploitative at the very same time the razor actually functions as a form of self-care for some), and this is one reason I find the One Love Manchester concert compelling. Manchester and the survivors of the blast and Ariana Grande and her touring team could absolutely use the safe space the concert is trying to create. As Lousley reminds us, the performed compassion of benefits isn’t simply fake feeling; the trauma Grande and the city and her fans experienced was real, and it’s especially audible in the moments Grande’s voice is pinched off mid-lyric. Let’s consider others who could use the safe space One Love Manchester is trying to create: victims of bombings and terror throughout the world. The music industry isn’t as eager to remind them that they matter. Self-care, it turns out, is easier for some to perform because the world is literally willing to invest in the care of those selves.

By contrast, Solange Knowles’s “Borderline (An Ode to Self-Care)” (from her 2016 album A Seat At The Table) is lyrically rooted in the black feminist work of community organizing and activism. The singer explains to her lover that she needs a night off so that she can have the resolve to go back out to the “borderline” and fight again. Self-care as warfare, indeed. The singer’s self-care has more than one purpose: it’s a time to remind herself that she matters, and it’s a time to restore the energy needed to go out and insist that her community matters. Instead of a bevy of pop stars lending their voices to create a safe space for her or an audience of adoring and grateful fans ready to take over if she can’t, Solange’s “Borderline” calls forth a more intimate setting. She multitracks her voice so that she collaborates and harmonizes with herself, with a faint doubling on the hook from Q-Tip, who is turned down in the mix and following Solange’s lead. “Borderline” is a mostly solo act of self-preservation that enables the singer to go out and create safe spaces for others.

This inward-to-outward focus of self-care is evident in the instrumentation. After a smooth piano-and-bass duet in the introduction, the kick drum enters at the 0:28 mark, overblown and rough around the edges. The effect sounds like oversaturation, where the signal’s gain is driven so that we lose some of the fidelity of its lower frequencies. This effect gives the kick a brighter timbre as the higher frequency overtones shine through and also muddies the lower frequencies so that they sound as if you’ve blown your car speakers and are getting noise in the mix that isn’t supposed to be there. The drum kit also includes a white noise sound (think “tsshhh”) that hits on the upbeat of the first, third, and fourth beats of each measure, joining the kick drum in creating a generally rough texture. This texture stands out because it sounds imperfectly mixed, like a sound engineer who messed something up. I hear in this a sonification of what Solange describes in her lyrics – a world that has frayed her edges, a world at war with her, a world disinterested at its best and hostile at its worst to the idea of her preservation. Hence, she pleas to retreat and preserve her own self.

The interlude that follows “Borderline” is the immediate payoff of this, as Solange sings with Kelly Rowland and Nia Andrews that she has “so much [magic], y’all, you can have it.” Then comes “Junie,” a fresh and energetic funk track that finds the singer back out on the activist grind after the night off that made it possible for her to return to the borderline.

As self-care proliferates in so many different practices performed by different selves, and as the term is emptied of meaning one hashtag at a time, one way we might track how power circulates through self-care is to listen to sonic representations of self-care. In Grande’s “One Last Time” performance at One Love Manchester we hear self-care staged and protected by cultural icons and government officials who assure attendees that their selves matter, while in Solange’s “Borderline” we hear self-care as an intimate, closed act that makes self- and community-preservation possible even when cultural icons and government officials refuse to participate in that preservation. In “One Last Time” we hear a community who shows up to help a singer when the world is hard, while in “Borderline,” we hear a singer having to reassure her own self that it’s okay to step away for a moment when the world is hard. By listening carefully in these moments, we can hear which selves are more readily recognizable as worthy of care—a chorus of voices surrounded and kept safe by heightened police presence—and which selves are more likely to have to perform care for themselves quietly or privately, for fear of retribution. Sound, in this instance, calls our attention to details that can let us more firmly hold onto a concept like self-care—a concept and series of practices that have been fundamental to the survival of black and queer women in a hostile world—that otherwise threatens to slip from our grasp. But hold on tight, and we just might make it back out to the borderline.

—

Featured image: Screenshot from Youtube video “Ariana Grande – One Last Time (One Love Manchester)” by user BBC Music

—

Justin Adams Burton is Assistant Professor of Music at Rider University. His research revolves around critical race and gender theory in hip hop and pop, and his book, Posthuman Rap, is available for pre-order (it drops October 2). He is also co-editing the forthcoming (2018) Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Music Studies. You can catch him at justindburton.com and on Twitter @j_adams_burton. His favorite rapper is one or two of the Fat Boys.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Unlearning Black Sound in Black Artistry: Examining the Quiet in Solange’s A Seat At the Table-Kimberly Williams

Trap Irony: Where Aesthetics Become Politics-Justin Burton

Listening to Sounds in Post-Feminist Pop Music-Robin James

You Got Me Feelin’ Emotions: Singing Like Mariah

Mariah Carey’s New Year’s Eve 2016 didn’t go so well. The pop diva graced a stage in the middle of Times Square as the clock ticked down to 2017 on Dick Clark’s Rockin New Year’s Eve, hosted by Ryan Seacrest. After Carey’s melismatic rendition of “Auld Lang Syne,” the instrumental for “Emotions” kicked in and Carey, instead of singing, informed viewers that she couldn’t hear anything. What followed was five minutes of heartburn. Carey strutted across the stage, hitting all her marks along with her dancers but barely singing. She took a stab at a phrase here and there, mostly on pitch, unable to be sure. And she narrated the whole thing, clearly perturbed to be hung out to dry on such a cold night with millions watching. I imagine if we asked Carey about her producer after the show, we’d get a “I don’t know her.”

These things happen. Ashlee Simpson’s singing career, such as it was, screeched to a halt in 2004 on the stage of Saturday Night Live when the wrong backing track cued. Even Queen Bey herself had to deal with lip syncing outrage after using a backing track at former President Barack Obama’s second inauguration. So the reaction to Carey, replete with schadenfreude and metaphorical pearl-clutching, was unsurprising, if also entirely inane. (The New York Times suggested that Carey forgot the lyrics to “Emotions,” an occurrence that would be slightly more outlandish than if she forgot how to breathe, considering it’s one of her most popular tracks). But yeah, this happens: singers—especially singers in the cold—use backing tracks. I’m not filming a “leave Mariah alone!!” video, but there’s really nothing salacious in this performance. The reason I’m circling around Mariah Carey’s frosty New Year’s Eve performance is because it highlights an idea I’m thinking about—what I’m calling the “produced voice” —as well as some of the details that are a subset of that idea; namely, all voices are produced.

I mean “produced” in a couple of ways. One is the Judith Butler way: voices, like gender (and, importantly, in tandem with gender), are performed and constructed. What does my natural voice sound like? I dunno. AO Roberts underlines this in a 2015 Sounding Out! post: “we’ll never really know how we sound,” but we’ll know that social constructions of gender helped shape that sound. Race, too. And class. Cultural norms make physical impacts on us, perhaps in the particular curve of our spines as we learn to show raced or gendered deference or dominance, perhaps in the texture of our hands as we perform classed labor, or perhaps in the stress we apply to our vocal cords as we learn to sound in appropriately gendered frequency ranges or at appropriately raced volumes. That cultural norms literally shape our bodies is an important assumption that informs my approach to the “produced voice.” In this sense, the passive construction of my statement “all voices are produced” matters; we may play an active role in vibrating our vocal cords, but there are social and cultural forces that we don’t control acting on the sounds from those vocal cords at the same moment.

Another way I mean that all voices are produced is that all recorded singing voices are shaped by studio production. This can take a few different forms, ranging from obvious to subtle. In the Migos song “T-Shirt,” Quavo’s voice is run through pitch-correction software so that the last word of each line of his verse (ie, the rhyming words: “five,” “five,” “eyes,” “alive”) takes on an obvious robotic quality colloquially known as the AutoTune effect. Quavo (and T-Pain and Kanye and Future and all the other rappers and crooners who have employed this effect over the years) isn’t trying to hide the production of his voice; it’s a behind-the-glass technique, but that glass is transparent. Less obvious is the way a voice like Adele’s is processed. Because Adele’s entire persona is built around the natural power of her voice, any studio production applied to it—like, say, the cavernous reverb and delay on “Hello” —must land in a sweet spot that enhances the perceived naturalness of her voice.

Vocal production can also hinge on how other instruments in a mix are processed. Take Remy Ma’s recent diss of Nicki Minaj, “ShETHER.” “ShETHER”’s instrumental, which is a re-performance of Nas’s “Ether,” draws attention to the lower end of Remy’s voice. “Ether” and “ShETHER” are pitched in identical keys and Nas’s vocals fall in the same range as Remy’s. But the synth that bangs out the looping chord progression in “ShETHER” is slightly brighter than the one on “Ether,” with a metallic, digital high end the original lacks. At the same time, the bass that marks the downbeat of each measure is quieter in “ShETHER” than it is in “Ether.” The overall effect, with less instrumental occupying “ShETHER”’s low frequency range and more digital overtones hanging in the high frequency range, causes Remy Ma’s voice to seem lower, manlier, than Nas’s voice because of the space cleared for her vocals in the mix. The perceived depth of Remy’s produced voice toys with the hypermasculine nature of hip hop beefs, and queers perhaps the most famous diss track in the genre. While engineers apply production effects directly to the vocal tracks of Quavo and Adele to make them sound like a robot or a power diva, the Remy Ma example demonstrates how gender play can be produced through a voice by processing what happens around the vocals.

Let’s return to Times Square last New Year’s Eve to consider the produced voice in a hybrid live/recorded setting. Carey’s first and third songs “Auld Lang Syne” and “We Belong Together”) were entirely back-tracked—meaning the audience could hear a recorded Mariah Carey even if the Mariah Carey moving around on our screen wasn’t producing any (sung) vocals. The second, “Emotions,” had only some background vocals and the ridiculously high notes that young Mariah Carey was known for. So, had the show gone to plan, the audience would’ve heard on-stage Mariah Carey singing along with pre-recorded studio Mariah Carey on the first and third songs, while on-stage Mariah Carey would’ve sung the second song entirely, only passing the mic to a much younger studio version of herself when she needed to hit some notes that her body can’t always, well, produce anymore. And had the show gone to plan, most members of the audience wouldn’t have known the difference between on-stage and pre-recorded Mariah Carey. It would’ve been a seamless production. Since nothing really went to plan (unless, you know, you’re into some level of conspiracy theory that involves self-sabotage for the purpose of trending on Twitter for a while), we were all privy to a component of vocal production—the backing track that aids a live singer—that is often meant to go undetected.

The produced-ness of Mariah Carey’s voice is compelling precisely because of her tremendous singing talent, and this is where we circle back around to Butler. If I were to start in a different place–if I were, in fact, to write something like, “Y’all, you’ll never believe this, but Britney Spears’s singing voice is the result of a good deal of studio intervention”–well, we wouldn’t be dealing with many blown minds from that one, would we? Spears’s career isn’t built around vocal prowess, and she often explores robotic effects that, as with Quavo and other rappers, make the technological intervention on her voice easy to hear. But Mariah Carey belongs to a class of singers—along with Adele, Christina Aguilera, Beyoncé, Ariana Grande—who are perceived to have naturally impressive voices, voices that aren’t produced so much as just sung. The Butler comparison would be to a person who seems to fit quite naturally into a gender category, the constructed nature of that gender performance passing nearly undetected. By focusing on Mariah Carey, I want to highlight that even the most impressive sung voices are produced, and that means that we can not only ask questions about the social and cultural impact of gender, race, class, ability, sexuality, and other norms may have on those voices, but also how any sung voice (from Mariah Carey’s to Quavo’s) is collaboratively produced—by singer, technician, producer, listener—in relation to those same norms.

Being able to ask those questions can get us to some pretty intriguing details. At the end of the third song, “We Belong Together,” she commented “It just don’t get any better” before abandoning the giant white feathers that were framing her onstage. After an awkward pause (during which I imagine Chris Tucker’s “Don’t cut to me!” face), the unflappable Ryan Seacrest noted, “No matter what Mariah does, the crowd absolutely loves it. You can’t go wrong with Ms. Carey, and those hits, those songs, everybody knows.” Everybody knows. We didn’t need to hear Mariah Carey sing “Emotions” that night because we could fill it all in–everybody knows that song. Wayne Marshall has written about listeners’ ability to fill in the low frequencies of songs even when we’re listening on lousy systems—like earbuds or cell phone speakers—that can’t really carry it to our ears. In the moment of technological failure, whether because a listener’s speakers are terrible or a performer’s monitors are, listeners become performers. We heard what was supposed to be there, and we supplied the missing content.

Sound is intimate, a meeting of bodies vibrating in time with one another. Yvon Bonenfant, citing Stephen Connor’s idea of the “vocalic body,” notes this physicality of sound as a “vibratory field” that leaves a vocalizer and “voyages through space. Other people hear it. Other people feel it.” But in the case of “Emotions” on New Year’s Eve, I heard a voice that wasn’t there. It was Mariah Carey’s, her vocalic body sympathetically vibrated into being. The question that catches me here is this: what happens in these moments when a listener takes over as performer? In my case, I played the role of Mariah Carey for a moment. I was on my couch, surrounded by my family, but I felt a little colder, like I was maybe wearing a swimsuit in the middle of Times Square in December, and my heart rate ticked up a bit, like maybe I was kinda panicked about something going wrong, and I heard Mariah Carey’s voice—not, crucially, my voice singing Mariah Carey’s lyrics—singing in my head. I could feel my vocal cords compressing and stretching along with Carey’s voice in my head, as if her voice were coming from my body. Which, in fact it was—just not my throat—as this was a collaborative and intimate production, my body saying, “Hey, Mariah, I got this,” and performing “Emotions” when her body wasn’t.

By stressing the collaborative nature of the produced voice, I don’t intend to arrive at some “I am Mariah” moment that I could poignantly underline by changing my profile picture on Facebook. Rather, I’m thinking of ways someone else’s voice is could lodge itself in other bodies, turning listeners into collaborators too. The produced voice, ultimately, is a way to theorize unlikely combinations of voices and bodies.

—

Featured image: By all-systems-go at Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

—

Justin Adams Burton is Assistant Professor of Music at Rider University, and a regular writer at Sounding Out! You can catch him at justindburton.com.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Gendered Sonic Violence, from the Waiting Room to the Locker Room-Rebecca Lentjes

I Can’t Hear You Now, I’m Too Busy Listening: Social Conventions and Isolated Listening–Osvaldo Oyola

One Nation Under a Groove?: Music, Sonic Borders, and the Politics of Vibration-Marcus Boon

Recent Comments