SO! Amplifies: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome! We are excited that today’s post on Wu Tsang’s Anthem, currently on view at the Guggenheim through September 6, 2021, is written by Freddie Cruz Nowell, co-author of the exhibition texts! He is related to the curator of the exhibition and cares deeply about the collaborative, creative endeavors of Wu Tsang & Moved by the Motion.

—

The artist and filmmaker Wu Tsang (b. 1982) creates atmospheric performances, video installations, and films that envelop audiences into spaces where narratives become sensually ambiguous, collective experiences. Tsang’s new site-specific installation, Anthem (2021), was conceived in collaboration with the singer, composer, and transgender activist Beverly Glenn-Copeland (b. 1944, Philadelphia) and harnesses the Guggenheim Museum’s cathedral-like acoustics to construct what the artist calls a “sonic sculptural space.”

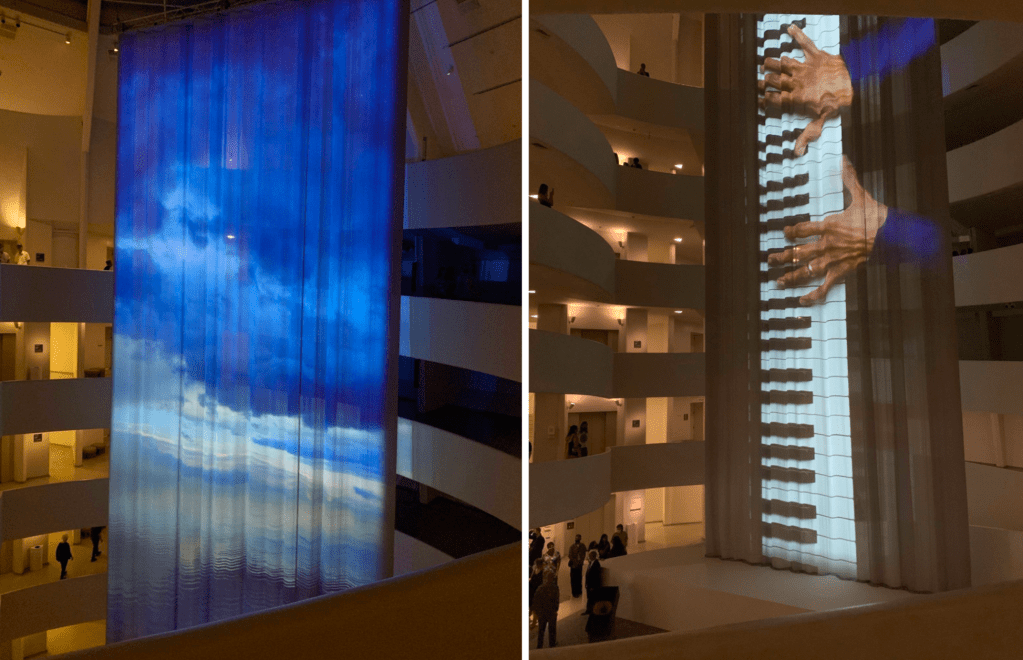

Occupying the entire rotunda, Anthem revolves around an immense, eighty-four-foot curtain sculpture that flows down from the building’s glass oculus. Projected onto this luminous textile is a “film-portrait” Tsang created of Glenn-Copeland improvising and singing passages of his music, including a cappella descants and his rendition of the spiritual “Deep River.” Filmed during the COVID-19 pandemic, near Glenn-Copeland’s home in rural Nova Scotia, this non-linear video alternates between scenes of the musician performing with various instruments and stunning landscape shots of the eastern seaboard sky.

Instrument and Landscape View of Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021), Images courtesy of The Guggenheim

Harnessing the generous sound-reflecting quality of the Guggenheim’s concrete walls, Anthem weaves Glenn-Copeland’s voice and body percussion into a larger tapestry of other voices and sounds placed along the museum’s circular ramp, building a soundscape that wraps around the space. When I asked the exhibition’s curator X Zhu-Nowell about the striking ethereal, translucent quality of the curtain sculpture, X remarked,

It was a collaboration with the textile company Kvadrat. Wu visited their showroom a few times to select textile from thousands of the samples. This particular textile called power is semi translucent (created almost a hologram feeling), but still able to capture the light from the projectors very well. Wu once said that ‘when there is a curtain in the space, it turns the space into a stage.’ Curtain is very important to Wu’s practice.

The installation’s dimmed light ambiance also veils the fourteen speakers that Tsang positioned along this darkened path, each of which plays a uniquely composed track that accompanies Glenn-Copeland’s music.

Working in collaboration with musician Kelsey Lu and the DJ, producer, and composer duo of Asma Maroof and Daniel Pineda, Tsang conceived this arrangement of sounds as a series of improvisatory responses inspired by the call of Glenn-Copeland’s voice. The musical responses created by this diverse group of musicians include ethereal string tremolos, dreamy whisper sequences, and impromptu drum patterns, among other ambient sounds that help cultivate an alluring and reverberant listening environment.

Harnessing the generous sound-reflecting quality of the Guggenheim’s concrete walls, Anthem weaves Glenn-Copeland’s voice and body percussion into a larger tapestry of other voices and sounds placed along the museum’s circular ramp, building a soundscape that wraps around the space. X Zhu-Nowell described the process for the exhibit’s speaker placement:

We had a few mock-up to test the speaker placement. The two loudspeakers are placed on the rotunda floor because it’s unique capacity to fill the entire rotunda. The 12 additional Bose speakers were placed throughout ramp 3 – 6. We evenly distributed them, 3 speakers for each ramp. Ultimately, the goal is to work with the unique acoustics of the building, and working with the decay, allowing the time and space for the sound to bound on the concrete walls. The piece is 18 mins long, and in a continuous loop. It was not designed to cultivate a single prime viewing location. Instead, the piece was built to be experienced as one move through the space, and 18 mins is around the pace of one walk from the bottom of the rotunda floor to the top of ramp 6.

Visitors are encouraged to traverse upward from the bottom of the museum to the top of the building, and vice versa, and explore how Anthem ascends and descends along the spiral path.

Alternative View of Ramp: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)

The title of this exhibition, Anthem, draws from lesser-known histories of the word meaning antiphon, a style of call-and-response singing associated with music as a spiritual practice. Unlike a conventional anthem, which amplifies the power of a song through loudness and uniform sound, this installation enhances the call of Glenn-Copeland’s voice by combining it with ambiguous vocal timbres, changing tints of ambient sound, and other heterogeneous sonic and visual textures. Within this lush yet complicated auditory environment, Tsang’s Anthem also cultivates moments of quiet, rest, and reflection, reimagining the rotunda as a compassionate atmosphere for collective listening and looking.

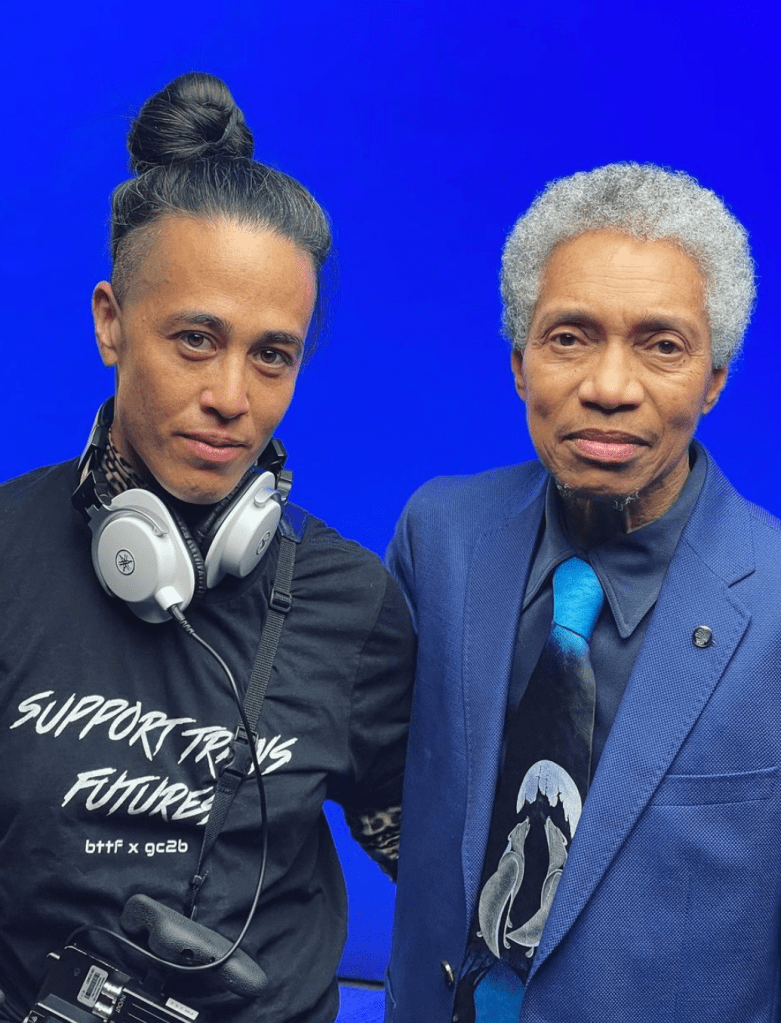

In addition to the immersive video installation on view in the rotunda, this exhibition also includes a touching companion film, titled “∞,” which visitors can access behind a luxe pleated curtain that divides the first floor side gallery from the main space. This video is a short interview that Tsang shot during the filming of Anthem of Glenn-Copeland and his partner, Elizabeth Glenn-Copeland, a theater artist, storyteller, and arts educator.

This dialogue captures autobiographical aspects of the couple’s intertwined creative process and artistic development, reflecting on myriad meanings of love in relation to their lives and work. Within the context of the oppressive and exploitive conditions of transgender “visibility” in contemporary culture, Tsang’s seemingly conventional yet uncommon record of this elderly and interracial couple exists in tension with the normative frame of transgender representation. It also extends the conversation within Tsang’s artistic practice around the centrality of collaboration, specifically long-term and intimate collaboration.

Photo of Wu and Glenn on set in Nova Scotia, from Wu Tsang’s IG feed

Since 2016, Tsang has frequently worked with a “roving band” of interdisciplinary artists called Moved by the Motion, cofounded with the artist Tosh Basco. Core members of this revolving cast include Maroof, Pineda, the dancer Josh Johnson, the cellist Patrick Belaga, and the poet and scholar Fred Moten. Anthem exemplifies how she uses collaboration as an aesthetic strategy for undoing conventional modes of authorship and to make space for marginalized narratives. For Tsang, “making art is an excuse to collaborate.”

On View at the Guggenheim, New York City, July 23-September 6, 2021

—

Featured Image: Still of banner/ installation View of Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021) at the Guggenheim, courtesy of curator X Zhu-Nowell

—

Frederick Cruz Nowell is a Ph.D. Candidate in Musicology at Cornell University. He is a scholar with a specialty in historical avant-gardes, and cross-disciplinary research into the history of music theory, contemporary art, and popular music. His dissertation research (Supervisor, Prof. Andrew Hicks) lies at the occult intersection of artistic experimentalism, Euro-American counterculture, and the history of music theory in the early twentieth century. It traces how speculative music-theoretical concepts (i.e., cosmic harmony, biological rhythms, color-harmony, and ontologies of sympathetic vibration) fused into the practices of European avant-garde artists via fashionable occult religious movements (i.e., Theosophy and Anthroposophy) and various cults of health and beauty (i.e., harmonic gymnastics, Eurythmics, free body culture (Freikörperkultur)). Intimately intertwined with one another, these social developments were integral to the larger infrastructure of the unwieldy “back to nature” Lebensreform (the reform of life) movement, which laid the foundations for progressive counterculture in the twentieth century.

Before pursuing graduate studies in musicology, Frederick was a University Fellow at Northwestern University in the Department of Art, Theory, & Practice, where he received an MFA. He also holds a BFA from SAIC (the School of the Art Institute of Chicago). Since 2018, he has co-curated exhibitions with X Zhu-Nowell under the moniker Passing Fancy.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig this:

Instrumental: Power, Voice, and Labor at the Airport--Asa Mendelsohn

SO! Amplifies: Anne Le Troter’s “Bulleted List”

“Finding My Voice While Listening to John Cage“–Art Blake

SO! Amplifies: Shizu Saldamando’s OUROBOROS

SO! Amplifies: Mendi+Keith Obadike and Sounding Race in America

Sound and Curation; or, Cruisin’ through the galleries, posing as an audiophiliac–reina alejandra prado

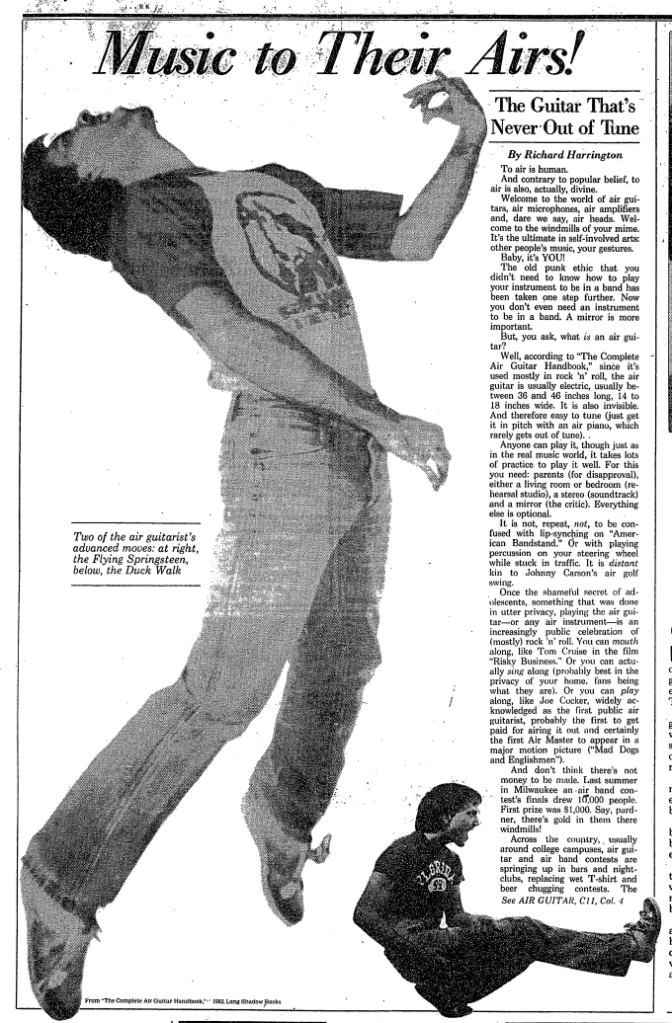

Listening in Plain Sight: The Enduring Influence of U.S. Air Guitar

The mention of “air guitar” might conjure images of the Bill and Ted series. Or Risky Business. Or maybe even Joe Cocker at Woodstock. You might think of air guitar as an embarrassing fan gesture. So when you hear there’s an annual U.S. Air Guitar competition, you might imagine an entirely superficial practice without any artistic merit. Maybe you just think of it as gimmicky. Or a celebration of the worst aspects of classic rock fandom and the white male guitar heroes that often populate its pantheon. In all honesty, I thought all of these things at first, until I began to take the competition seriously.

I did not realize, for example, that air guitar competitions have an enduring history since the late 1970s, existing as an incredibly influential popular music pantomime practice that informs platforms like TikTok. I did not realize how invested contemporary competitors could be—dedicating years to learning the craft. And I did not realize how these reconstructions of guitar solos could creatively rupture the relationship between guitar virtuosity and privileged identities in popular music’s past.

The U.S. Air Guitar Championships began in 2003 as the national branch of the Air Guitar World Championships, which began in 1996 in Oulu, Finland. The competition emerged as a bit of a joke alongside the Oulu Music Video Festival. Eventually, two people—Cedric Devitt and Kriston Rucker—founded U.S. Air Guitar, which expanded across the country (thanks, in part, to the influential documentary Air Guitar Nation). Today, folks compete in order to advance from local to regional to the national competition, ultimately hoping to be crowned the best air guitarist in the nation and sent to Finland to represent the United States (think: Eurovision but air guitar). United States air guitarists do incredibly well in the international competition, although they face formidable air guitarists from Japan, France, Canada, Australia, Russia, and Germany (as well as less-formidable air guitarists from elsewhere).

In each competition, competitors perform as personas, such as Rockness Monster, AIRistotle, Agnes Young, and Mom Jeans Jeanie. They don elaborate costumes. They painstakingly practice elaborate choreographies and compete in some of the most famous musical venues in the country—from Bowery Ballroom to the Black Cat. Competitors stage routines that bring a particular 60-second rock solo to life, using their bodies to simulate playing the real guitar (what air guitarists call “there guitar”). Think of these as gestural interpretations of the affective power of guitar solos, rather than a mechanical reproduction of particular chords, frets, and licks. They use their bodies to draw out timbre, rhythm, and pitch, and they also play with the juxtaposition of their own identities and those of the original artists. Judges evaluate performances based on three criteria:

· Technical merit (does the pantomime more or less correspond to the guitar playing in the music?)

· Stage presence (is it entertaining?)

· ‘Airness’ (does the performance transcend the imitation of the real guitar to become an art form in and of itself?)

Scores are given on a figure skating scale, from 4 to 6. So a perfect score is 666 from the three judges. Winners in the first round advance to the second round, where they must improvise an air guitar routine to a surprise song selection.

As part of my ethnographic work on air guitar, I competed in a local competition, where I was crowned third best air guitarist in Boston in the year 2017 (a distinction that will likely never appear on my CV). I have also conducted fieldwork in Finland twice and attended countless competitions in the U.S. I judged the 2019 U.S. Air Guitar Championships in Nashville alongside Edward Snowden’s lawyer, which resulted in a three-way air off to crown a winner.

Competitions depend on recruiting new competitors, celebrity judges, and large crowds, all of which can be at odds with creating an inclusive community. Organizers have worked hard to eliminate racist, sexist, ableist, and other forms of discriminatory language from judges’ comments. Women within U.S. air guitar have formed advocacy groups. The proceeds of the most recent competitions have been donated to Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice, which took up the case of a disabled Black veteran named Sean Worsley who was incarcerated for playing air guitar to music at a gas station. Both organizing bodies at the national and international level emphasize world peace as central to their mission.

Air guitar routines are themselves political statements too. These acts of musical interpretation enable women, BIPOC, and disabled performers to author sounds credited to guitar idols, like Eddie Van Halen or Slash. Performers make arguments about their access to popular music, using only their bodies. Sydney Hutchinson’s work examines how air guitar can challenge Asian American stereotypes and gendered conceptions of dance.

My current work revolves around disabled air guitarists. Andres SevogiAIR drew me in, as a result of his expressive flamenco-inspired seated style he called “chair guitar.” He passed away but left me with an enduring appreciation for air guitar’s ability to challenge conventional virtuosity, a term that can often reproduce an ableist link between physical ability and musical virtue. I came to appreciate how air guitarists could invent imaginary instruments that serve their particular bodies. I witnessed competitors coupling chronic illness and impairments with air guitar routines, as well as competitors using air guitar to fully amplify their struggles with cancer.

I also came to appreciate how air guitarists embrace stigma (e.g., madness, craziness, and gendered forms of listening), turning taboo into a source of creativity. This led to academic writing that traces the history of madness in relation to air guitar, showing how imaginary instrument playing has often been pathologized, and yet contemporary disabled air guitarists reclaim these accusations of insanity as a source of power.

* * *

A few weeks ago, I received a request from Lieutenant Facemelter to judge the Midwestern Online Regional U.S. Air Guitar Competition. I accepted. As with many things these days, the contemporary competition has morphed into a Twitch-hosted online spectacle, featuring combinations of live and pre-recorded elements. One woman gave birth between first- and second-round performances (made possible by a multi-day filming period for an asynchronous part of the online competition). One man’s air guitar performance evoked an exorcism in his basement. Another middle-aged competitor competed while suffering the side effects of his second shot of coronavirus vaccine, ultimately winning the competition with a pro-vaccination message. His parents appeared in the livestream when he accepted the award, and the host of the show–the Master of Airimonies–jokingly said to them: “You two must be so proud.”

I think of U.S. Air Guitar as a stained-glass window, through which prisms of popular music history shine through. The competition can bring troubling facets of that history to light, but the competition can also revise that history (or, at least, reimagine how that history can influence the future). Either way, performers celebrate the idea that rock solos live most powerfully in the embodied listening practices of everyday people. Listening becomes the subject of these performances–the source material for these persuasive displays of music reception. Indeed, air guitar can be one of the strangest things you’ll never see.

The competition continues this summer.

—

Featured Image: US Air Guitar National Finals, The Midland Theater, Kansas City, MO, August 9, 2014, by Flickr user Amber, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Byrd McDaniel | Byrd is a scholar who researches disability, digital cultures, and popular music. He currently works as a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry at Emory University. His forthcoming book–Spectacular Listening— traces the rise of contemporary practices that treat listening as a performance, including air guitar, podcasts, reaction videos, and lip syncing apps. Byrd is enthusiastic about work that addresses any facet of air guitar, including global and historical approaches. He welcomes outreach from those who want to research these topics.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening–Airek Beauchamp

Digital Analogies: Techniques of Sonic Play–Roger Moseley

Experiments in Aural Resistance: Nordic Role-Playing, Community, and Sound—Aaron Trammell

Recent Comments