Learning to Listen Beyond Our Ears: Reflecting Upon World Listening Day

World Listening Day took place last week, and as I understand it, it is all about not taking sound for granted – an admirable goal indeed! But it is worth taking a moment to consider what sorts of things we might be taking for granted about sound as a concept when we decide that listening should have its own holiday.

took place last week, and as I understand it, it is all about not taking sound for granted – an admirable goal indeed! But it is worth taking a moment to consider what sorts of things we might be taking for granted about sound as a concept when we decide that listening should have its own holiday.

One gets the idea that soundscapes are like giant pandas on Endangered Species Day – precious and beautiful and in need of protection. Or perhaps they are more like office workers on Administrative Professionals’ Day – crucial and commonplace, but underappreciated. Does an annual day of listening imply an interruption of the regularly scheduled three hundred and sixty four days of “looking”? I don’t want to undermine the valuable work of the folks at the World Listening Project, but I’d argue it’s equally important to consider the hazards of taking sound and listening for granted as premises of sensory experience in the first place. As WLD has passed, let us reflect upon ways we can listen beyond our ears.

At least since R. Murray Schafer coined the term, people have been living in a world of soundscapes. Emily Thompson provides a good definition of the central concept of the soundscape as “an aural landscape… simultaneously a physical environment and a way of perceiving that environment; it is both a world and a culture constructed to make sense of that world.”(117) As an historian, Thompson was interested in using the concept of soundscape as a way of describing a particular epoch: the modern “machine age” of the turn of the 20th century.

Anthropologist Tim Ingold has argued that, though the concept that listening is primarily something that we do within, towards, or to “soundscapes” usefully counterbalanced the conceptual hegemony of sight, it problematically reified sound, focusing on “fixities of surface conformation rather than the flows of the medium” and simplifying our perceptual faculties as “playback devices” that are neatly divided between our eyes, ears, nose, skin, tongue, etc.

Stephan Helmreich took Ingold’s critique a step further, suggesting that soundscape-listening presumes a a particular kind of listener: “emplaced in space, [and] possessed of interior subjectivities that process outside objectivities.” Or, in less concise but hopefully clearer words: When you look at the huge range of ways we experience the world, perhaps we’re limiting ourselves if we confine the way we account for listening experiences with assumptions (however self-evident they might seem to some of us) that we are ‘things in space’ with ‘thinking insides’ that interact with ‘un-thinking outsides.’ Jonathan Sterne and Mitchell Akiyama, in their chapter for the Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies, put it the most bluntly, arguing that

Recent decades of sensory history, anthropology, and cultural studies have rendered banal the argument that the senses are constructed. However, as yet, sound scholars have only begun to reckon with the implications for the dissolution of our object of study as a given prior to our work of analysis.(546)

Here they are referring to the problem of the technological plasticity of the senses suggested by “audification” technologies that make visible things audible and vice-versa. SO!’s Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman has also weighed in on the social contingency of the “listening ear,” invoking Judith Butler to describe it as “a socially-constructed filter that produces but also regulates specific cultural ideas about sound.” In various ways, here, we get the sense that not only is listening a good way to gain new perspectives, but that there are many perspectives one can have concerning the question of what listening itself entails.

But interrogating the act of listening and the sounds towards which it is directed is not just about good scholarship and thinking about sound in a properly relational and antiessentialist way. It’s even less about tsk-tsking those who find “sound topics” intrinsically interesting (and thus spend inordinate amounts of time thinking about things like, say, Auto-Tune.) Rather, it’s about taking advantage of listening’s potential as a prying bar for opening up some of those black boxes to which we’ve grown accustomed to consigning our senses. Rather than just celebrating listening practices and acoustic ecologies year after year, we should take the opportunity to consider listening beyond our current conceptions of “listening” and its Western paradigms.

For example, when anthropologist Kathryn Lynn Guerts first tried to understand the sensory language of the West African Anlo-Ewe people, she found a rough but ready-enough translation for “hear” in the verb se or sese. The more she spoke with people about it, however, the more she felt the limitations of her own assumptions about hearing being, simply, the way we sense sounds through our ears. As one of her informants put it, “Sese is hearing – not hearing by the ear but a feeling type of hearing”(185). As it turns out, according to many Anlo-ewe speakers, our ability to hear the sounds of the world around us is by no means an obviously discrete element of some five-part sensorium, but rather a sub-category of a feeling-in-the-body, or seselelame. Geurts traces the ways in which the prefix se combines with other sensory modes, opening up the act of hearing as it goes along: sesetonume, for example, is a category that brings together sensations of “eating, drinking, breathing, regulation of saliva, sexual exchanges, and also speech.” Whereas English speakers are more inclined to contrast speech with listening as an act of expression rather than perception, for the Anlo-Ewe they can be joined together into a single sensory experience.

“Listening, Regent Street, London, 17 December 2011” by Flickr user John Perivolaris, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The ways of experiencing the world intimated by Geurts’ Anlo-Ewe interlocutors play havoc with conventionally “transitive,” western understandings of what it means to “sense” something (that is, to be a subject sensing an object) let alone what it means to listen. When you listen to something you like, Geurts might suggest to us that liking is part of the listening. Similarly, when you listen to yourself speak, who’s to say the feeling of your tongue against the inside of your mouth isn’t part of that listening? When a scream raises the hairs on the back of your neck, are you listening with your follicles? Are you listening to a song when it is stuck in your head? The force within us that makes us automatically answer “no” to questions of this sort is not a force of our bodies (they felt these things together after all), but a force of social convention. What if we tried to protest our centuries-old sensory sequestration? Give me synaesthesia or give me death!

Indeed, synaesthesia, or the bleeding-together of sensory modes in our everyday phenomenological experience, shows that we should loosen the ear’s hold on the listening act (both in a conceptual and a literal sense – see some of the great work at the intersections of disability studies and sound studies). In The Phenomenology of Perception, Maurice Merleau-Ponty put forth a bold thesis about the basic promiscuity of sensory experience:

Synaesthetic perception is the rule, and we are unaware of it only because scientific knowledge shifts the centre of gravity of experience, so that we have unlearned how to see, hear, and generally speaking, feel, in order to deduce, from our bodily organization and the world as the physicist conceives it, what we are to see, hear and feel. (266)

Merleau-Ponty, it should be said, is not anti-science so much as he’s interested in understanding the separation of the senses as an historical accomplishment. This allows us to think about and carry out the listening act in even more radical ways.

Of course all of this synaesthetic exuberance requires a note to slow down and check our privilege. As Stoever-Ackerman pointed out:

For women and people of color who are just beginning to decolonize the act of listening that casts their alternatives as wrong/aberrant/incorrect—and working on understanding their listening, owning their sensory orientations and communicating them to others, suddenly casting away sound/listening seems a little like moving the ball, no?

To this I would reply: yes, absolutely. It is good to remember that gleefully dismantling categories is by no means always the best way to achieve wider conceptual and social openness in sound studies. There is no reason to think that a synaesthetic agenda couldn’t, in principle, turn fascistic. The point, I think, is to question the tools we use just as rigorously as the work we do with them.

—

Owen Marshall is a PhD candidate in Science and Technology Studies at Cornell University. His dissertation research focuses on the articulation of embodied perceptual skills, technological systems, and economies of affect in the recording studio. He is particularly interested in the history and politics of pitch-time correction, cybernetics, and ideas and practices about sensory-technological attunement in general.

—

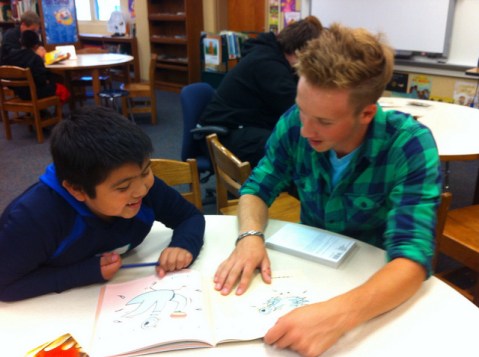

Featured image: “” by Flickr user woodleywonderworks, CC-BY-2.0

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Snap, Crackle, Pop: The Sonic Pleasures of Food–Steph Ceraso

“HOW YOU SOUND??”: The Poet’s Voice, Aura, and the Challenge of Listening to Poetry–James Hyland

SO! Amplifies: Eric Leonardson and World Listening Day 18 July 2014–Eric Leonardson

This April forum,

This April forum,

Recent Comments