Finding My Voice While Listening to John Cage

Editor’s Note: Today I bring you installment #4 of Sounding Out!‘s blog forum on gender and voice! Last week Regina Bradley put the soundtrack of Scandal in conversation with race and gender. The week before I talked about what it meant to have people call me, a woman of color, “loud.” That post was preceded by Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book, on the gendered soundscape. We have two more left! In the next few weeks we’ll have A.O. Roberts with synthesized voices and gender, and lastly Robin James with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy.

This week guest writer and professor Art Blake shares with us a personal essay. He talks about how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage. So, lean in, close your eyes, and try not to jump to conclusions before you listen. –Liana M. Silva, Managing Editor

—

When I walked into the packed lecture theatre at the start of the Fall term 2012 I was hoping, more than any other year, to sound convincing. I had been teaching for 11 years by that time so I knew what I was doing. But I was walking into class as a man, for the first time. I was not sure if my newly thickening vocal chords would hold me at a convincing “male” pitch or if I would be able to project that developing voice to the back of the room. I thought I looked “manly” enough; but would I sound manly?

I had been researching and teaching about sound since 2003 but had not confronted myself as a potential object of study until I was preparing to return to teaching in 2012 following the early phase of my transition from female to male. My notions of “masculinity” have never been conventional: as a somewhat incompetent butch-ish lesbian I’d attempted but never “mastered” the appropriate vocal or bodily swagger. I abandoned those conventions to evolve my own more elfin, more queer swish. But on that first day back in the classroom, and for much of that term, I felt I needed to produce “normal guy”—a gender-identity category I didn’t believe in or want to become—so I might feel secure enough later to explore and tweak my newly gendered voice and body. I wanted a baseline from which I could re-build. I wasn’t ready to be out as trans* in the classroom. Yes, I was in a closet; but I needed it to serve as a dressing room, a place of private preparation, rather than as a long-term hiding place.

I started testosterone therapy in January 2011, on a low dose as is the standard of care. As my doctor increased my dose over the months, I noticed the beginning of the physical changes I’d been waiting for: more body hair, muscle development, and a hoarsening voice. I earnestly weighed and measured myself, worked out at the local YMCA, chose a new name and made it legal … and dealt with months of severe anxiety and depression. Puberty isn’t fun, and doing it again in my forties, as part of gender transition, was not the seamless story of celebration familiar from the YouTube videos I’d watched obsessively charting other guys’ transitions. Those videos were mostly about looking male, not sounding male, and rarely addressed transitioning at work, within a profession.

I spoke to a transman, also an academic, to discuss the challenges of transitioning in our profession. His version of masculinity was more conservative than I had expected, and a bit homophobic, but what really worried me was his concern about my voice: “I really hope for your sake your voice changes,” he said. What did he mean? Would I fail the test of public masculinity not only because I wasn’t wearing a jacket and tie but because I sounded feminine?

All those images of authoritative, sonorous, academic masculinity flooded me with panic. Testosterone wasn’t going to make me any taller, give me an Adam’s apple, or bigger hands and feet. I was going to be a small guy, standing at the front of the classroom with years of academic expertise, but a mismatched voice might undermine that basic authority. Female academics, like most female professionals, have to work harder for the respect of students as well as colleagues; we all have seen or know of evidence for this sexism. Men, just by being perceived as male, get more generous teaching evaluations from undergraduates. As I transitioned I found myself grasping for that authority in a way I hadn’t imagined before.

In search of help, I went to see Dr. Gwen Merrick, a therapist in the Speech Pathology section of Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital. Gwen is known in the trans* community and trans* health networks for her work with transwomen. To my surprise I was her first transmale patient. While admitting her lack of experience she also welcomed the challenge to help masculinize my voice and lessen my anxiety around my vocal-gender dysphoria.

So we began: she examined my vocal chords (properly “vocal folds”). We then moved on to discuss my goals and concerns, and began the process of recording my voice—measuring its volume and tone, listening to the digital recordings, and training me to hear and then adjust my vocal pitch and speech rhythms. She gave me vocal exercises for homework, and taught me how to relax and move my larynx lower in my throat to lengthen it and create a lower pitch. Gwen also encouraged me to imagine myself into the vocal change I sought. I tried taking up more space as I sat in her office, head up and chest out, adopting an attitude of greater confidence, channeling the burliest and butchest of my cismale friends.

My scholarly life took a nosedive during those months on medical leave. The first piece of scholarship I re-engaged with during this time was something I’d been thinking about for years: an article about the composer John Cage‘s voice. I wanted to write about the disconnect I had heard between Cage’s speaking voice and my assumptions about him based on his appearance. I sought to hear Cage’s voice in the context of the post-1945 period when he rose to great prominence as a composer. What I gradually came to hear as I returned to this research was how and why Cage’s voice, within the context of the 1950s in particular, spoke to me so profoundly as I emerged publically as trans*.

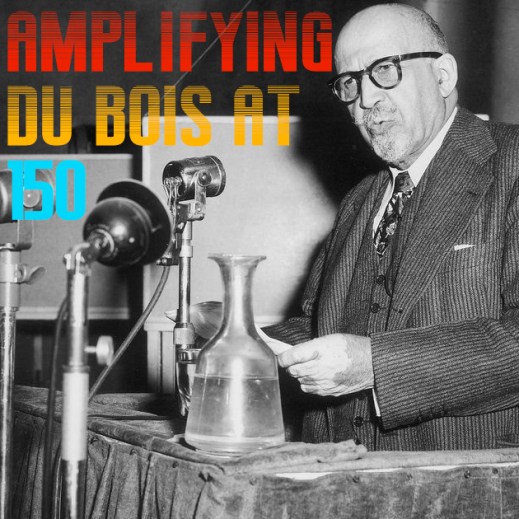

“Photograph of John Cage talking to another guest at a drinks reception at the Cage/Cunningham Residency at the Laban Centre, Laurie Grove, London, July 1980” by Flickr user Laban Archive,

I first heard his recorded speaking voice while teaching some of his work in an early iteration of my sound studies seminar. I’d seen photographs of Cage as a middle-aged and older man; from those images of a tall, craggy-faced guy in a sports jacket or woolly sweater, I had expected to hear a baritone, chest-resonant, rich “masculine” voice. Instead, Cage’s voice was light, with very little chest register, almost breathy sometimes, and inflected with the rhythm and occasional sibilance of what I “recognized” as a gay male (American) voice.

How had Cage navigated the homophobia of the 1950s with a voice like that? Was what I heard as his audible difference perceived that way in the postwar period as he rose to prominence as a modernist composer? According to some older gay men I’d interviewed for my 2004 radio documentary on the early gay leather scene in the 1950s, they had consciously altered their voices in everyday situations where they didn’t want (or couldn’t risk) being heard as gay. As one guy mentioned, for such circumstances he adopted his “gas station voice”—a vocal pitch and style to get him through such commonplace moments of public masculinity as talking to the gas station attendant. I wondered if Cage also kept one voice in the closet and adopted another one he needed based on circumstance.

As I sought my own “gas station voice” in the fall of 2012, returning to Cage and listening to his voice in his 1956 composition Indeterminacy helped gradually lessen my anxiety about audibly “passing.” Listening to Indeterminacy, a series of stories occasionally interwoven with a piano, allowed me to not only hear but also admire Cage’s voice and the political resonance it may have held in McCarthy-era America.

I looked for examples of Cage speaking outside of his own compositions, someplace more public—someplace where I might hear him put his voice in the closet and butch himself up for the public ear. I looked for ways to contextualize Cage’s voice in the era of determinacy — mainstream 1950s America, high modernist, planned, and in love with postwar military-industrial efficiency and the performance of expertise.

My urban history self focused on New York in the 1950s, listening for other voices resonant with the era’s “structure of feeling.” If heard by a 1958 resident of New York City, Indeterminacy might have sounded somewhat familiar. The experience of listening to all or parts of Indeterminacy resonated with the interruptions, the drowned-out words, the overlapping and oppositional sounds, the proximity of people and machinery, which characterized Manhattan (in particular) in the late 1950s. Cage spent periods of time in New York City as well as upstate in the 1950s, moving between different art scenes. What did New York sound like in the 1950s? The Puerto Rican migration and urban renewal re-shaped the city’s soundscape on the west side, as documented by sound recordist Tony Schwartz and re-presented through the musical West Side Story. I had written about those encounters with audible difference but now wanted to listen more closely. What did the city’s infamous urban planner, master of urban renewal, Robert Moses sound like? What did his outspoken critic Jane Jacobs sound like? And how might I hear their contemporary John Cage in this context with reference to the notion of “indeterminacy”?

Within a Cold War-McCarthyist context, voices represented an aspect of the suspect-self available for investigation, interrogation, and pathologizing. I identified, to an extent, with such a predicament, such a fear of exposure and of the negative consequences I presumed would follow. While I listened to John Cage’s and others’ voices from this period, I listened for how Cold War authorities may have heard them. John Cage’s voice offers indeterminacy itself, hovering in the margins of the tonal, rhythmic, and pitch ranges of conventionally “masculine” and “feminine” voices at mid-century. Despite our contemporary resistance to stereotyping, one hears in Cage’s gendered oscillation, mixing minor chest resonance with the higher, softer, breathier sounds, a definitive type of “gay” male voice: the sissy voice. As Craig Loftin has argued in “Unacceptable Mannerisms: Gender Anxieties, Homosexual Activism, and Swish in the United States, 1945-1965,” during the 1950s gay men as well as the heteronormative majority, produced intense hostility to the archetype of the “sissy,” whose voice and body movements marked him as politically problematic in the context of both homophile activism and Cold War homophobia.

Paul J. Moses aimed to analyze in his 1954 book, The Voice of Neurosis (one of the many works in the field of “personality studies” popular in the 1950s) the personality from the speaking voices of his subjects with a method he called “creative hearing.” Moses’s work suggested that the voice revealed the “true” personality, belying a person’s efforts to disguise themselves through dress, work or relationships. Such secrets could be heard, or listened for, through Moses’ “creative hearing.” Of course, when he published his work in 1954, the Cold War made aural surveillance, the use of listening devices, as well as the “creative hearing” of expert listeners, a crucial weapon in a war of secrets.

In January 1960 John Cage appeared as a contestant on the popular television game show I’ve Got a Secret (CBS, 1952-1967), a show that perfectly channeled concerns about hidden identities at the heart of public and Congressional anti-Communism within Cold War politics in the United States. Derived from the radio show What’s My Line in which a celebrity panel tried to discover a person’s job, in I’ve Got a Secret the panel tried to uncover the contestant’s “secret,” normally something unusual or perhaps embarrassing. The I’ve Got a Secret format played with the tension between who knew and who did not know the contestant’s “secret.” After being introduced by name and hometown, the show’s host asked each contestant to whisper their secret in his ear. During the on-camera intimacy of mouth-to-ear divulgence, text of the revelation scrolled up over the TV screen for the viewers at home and was visible to the studio audience. The panel of celebrity inquisitors could only observe the studio audience’s responses of laughter, shock, or titillation.

John Cage’s appearance on the show was devoted to the performance of his “secret.” Cage whispered to host Garry Moore that he had made a musical composition using a bathtub, jugs, a blender, radios, a piano, a tape recorder, a watering can, and other common household objects. In an absurdist version of a laboratory experiment, Cage darted from one to the other object, pressing buttons, pouring liquids, hitting radios, putting flowers in a bathtub, all the while holding and responding to the stopwatch in his hand. Cage performed inefficiency and absurdity, inviting laughter, the opposite of industrial modernism’s demand for logic, order, and compliance to norms. Cage’s non-compliant, queer performance and composition satirized the efficiency experiments of twentieth century time-management experts; the “Water Walk” “instruments”, all objects from everyday life, bear no productive relation to each other and are not arranged in a manner producing efficiency. Cage thus queered the modern, as typified in mid-20th century American industry, corporate capitalism, and national infrastructure projects such as urban renewal.

Cage’s voice provides an added and unexpected queer flourish to his TV appearance on I’ve Got a Secret. The sound of Cage’s voice (soft, higher-pitched, lilting, slightly sibilant) contrasts with his formal attire and hetero-normative environment. Cage’s voice reveals a “secret”—his homosexuality—different from the “secret” featured on the show. Like most Cold War secrets, it was not a secret to him or his close friends but was supposed to function as a secret in that historical context. Cage resisted, consciously or not, the vocal closet; he made no attempt, as far as I can hear, to alter his voice in the very public context of a live television show. John Cage appears happy, playful, and delighted to perform for the audience. His antic performance of “Water Walk” endeared him to a mid-century audience who came ready to enjoy the show’s pleasurable revelation of secrets.

Other “hearings” of Cage’s non-normative self might well have produced a less relaxed response from those same audience members: his voice at a Congressional HUAC hearing; his voice overheard on the street or in a cafe. The gay or gender non-conformist audience members may have thrilled to Cage’s double-edged performance of his “secrets,” or they may have cringed at such possible revelations, in fear of their also being heard as different but lacking the protection of Cage’s (albeit limited) celebrity.

Standing at the front of the lecture theatre in September 2012, I felt I too had a secret, and my heart pounded, my stomach jittered for fear of its revelation. But, as I continued to listen to Cage’s voice on a recording of Indeterminacy, and to think through his TV performance on I’ve Got a Secret, I grew more able to let go of my fear of being heard as trans*. I heard and saw Cage as a man who resisted convention and a culture of fear and judgment.

Four years on, I no longer worry whether or not my voice signals my transmasculinity. I can’t control how my students or anyone else hears me, or the joy, confusion, curiosity, or disgust their hearing me may produce in them. My last term’s teaching evaluations, from Fall 2014, for that same large lecture class I first taught in Fall 2012, included many positive comments about my teaching; they also included a student’s written comment describing my voice as “gentle” and thus sometimes harder to hear. I will wear a microphone for volume, if needs be, to increase my audibility. But I feel no need to alter what that student heard as “gentle.” I can live with gentle, for which I thank John Cage.

—

Featured image: from Issue Project Room

—

Art Blake is an Associate Professor in the Department of History at Ryerson University, Toronto, where he also teaches and supervises grad students in the Communication and Culture program. He is completing his second book, Talk To Me: Mediated Voices in 20th Century America. His new research concerns contemporary international urban “maker” cultures.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Music to Grieve and Music to Celebrate: A Dirge for Muñoz—Johannes Brandis

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice—Yvon Bonefant

Sound as Art as Anti-environment—

Recent Comments