On “The Dream Life of Voice:” A Rerecording of Bernadette Mayer Reading from The Ethics of Sleep

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? Today John Melillo offers us a multi-track rerecording of Bernadette Mayer reading from The Ethics of Sleep. He urges us to “value illegibility over legibility and the abstract over the figured. If we deemphasize voice, we acknowledge the ways in which voices can undo themselves in their production.” –SO! Ed. Jennifer Stoever

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? Today John Melillo offers us a multi-track rerecording of Bernadette Mayer reading from The Ethics of Sleep. He urges us to “value illegibility over legibility and the abstract over the figured. If we deemphasize voice, we acknowledge the ways in which voices can undo themselves in their production.” –SO! Ed. Jennifer Stoever

What separates voice from noise? At what point does a voice dissipate into the sounds that surround and, at times, threaten to overwhelm it? In “The Dream Life of Voice,” I draw special attention to the ways in which attending to voice—and its precarity—entails a heightened sensation of noise. Through my manipulation of recorded audio in this project, I argue that noise is not merely an unwanted or surprising sound: it is the material sonic trace of an unconscious listening that continues to work beneath, around, and within a conscious listening to voice.

In this audio recording, I have taken a selection from a reading by the poet Bernadette Mayer that I recorded for the Tucson-based poetry and arts organization, POG, on February 6, 2016. I used a standard SM58 microphone, a digital audio recording interface, and the software program Logic. Mayer is known as a poet who has tested the boundaries of poetic statement through poems that engage with the conscious and unconscious uses of language. In this selection, she reads a long poem from her book The Ethics of Sleep (Trembling Pillow Press, 2011) on the power of dreams and dream language. In the performance, the poem and her voice create a sense of continuous movement, with quick and unpredictable turns of phrase sutured together by a syntactic and rhythmic familiarity. In this audio project, I flatten the sonic space in this recording of Mayer in order to abstract the voice and place it within a wider frequency spectrum of noise. Just as Mayer’s words engage her book’s title, my audio project argues for the possibility of an unconscious but engaged listening to noise.

“Bernadette Mayer’s 1971 performance piece, Memory, for which she shot a roll of 35 mm film and composed a journal entry every day for a month, addresses issues of time, narrative, nostalgia, narcissism, and documentation, along with the possibilities of art and poetry in relation to perception and remembrance.” – Marcella Durand, Hyperallergic

Roland Barthes famously defined listening as “a psychological act” and hearing as a mere “physiological phenomenon” (Barthes 246). In a kind of doubling of listening’s action, the work of formulating or understanding a voice involves a selecting for sounds as a significant figure—the mark of a person or persona. Yopie Prins calls the recorded, mediated voice of 19th century poetry a “voice inverse,” a prosthetic figure composed out of its imprint by mechanical means, whether those means be metrical, print-based, or phonographic (48). Of such mechanical means—in particular, audio recording—Charles Bernstein argues, “the mechanical semblance of voice has become the signal in a medium whose material base is sonic, not vocal. In such a phonic economy, noise is sound that can’t be recuperated as voice” (110). In taking up this binary phonic economy, however, I want to hear how voice and noise interweave and interpenetrate, with the sonic figuration of voice as a threshold that opens out to other sounds not ostensibly included in its composition.

Press Play to hear “The Dream Life of Voice” by John Melillo, a rerecording of Bernadette Mayer reading from The Ethics of Sleep.

In this 12’43” audio recording, I have devised an analytic and synthetic method that allows listeners to reframe and refocus their hearing toward the trace of noise in voice, as well as the voice’s trace in noise. The final recording is composed of three simultaneous tracks, each of which represents a different “noise regime” in relation to the poet’s voice.

The first, original, track contains the “straight” recording of Mayer’s voice and speech: one hears her performance of the poem loud and clear. This is the imprint of voice on the recording mechanism in a phonic economy of voice and noise, in which voice seems to counteract and silence its opposite.

The second track contains a manipulated version of the original track, in which I have removed all the audio of Mayer’s voice and constructed a “background noise” track from what remains. In this method, I simply cut out Mayer’s voice from the audio file, keeping only the “silent” moments of the reading. I then combined and looped these fragments to create an amplified track of the background sounds—sounds of the people in the room, cars outside, a train passing, and the recording medium itself (hiss). In this way, I flip the binary toward that which is explicitly unheard in the recording.

For the third track, I manipulated the original recording by applying a Fast Fourier Transform with the software program Spear. This method breaks down the sounds into a collection of sine wave frequencies that can be graphically manipulated in the software program. I then removed the loudest frequencies (present mostly as Mayer’s voice) in order to emphasize the upper partials and continuous non-vocal frequencies masked by the force of the voice. This track marks a synthesis in which voice blends with and disappears into the frequency spectrum.

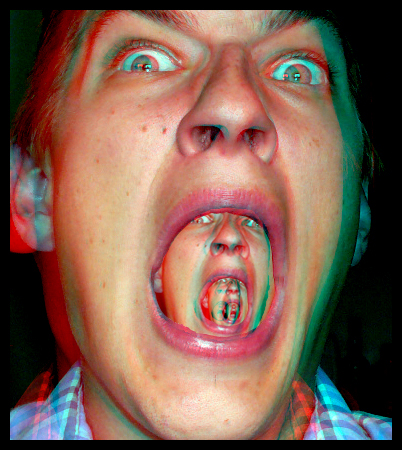

“Unsmoothed” by Flickr user Felix Morgner, CC BY-SA 2.0

I combined these three tracks and slowly adjusted the volume for each one. The track with Mayer’s voice starts off as the loudest of the three. Her comments on the noise from a train that has just passed begin the montage. This track then undergoes a long, slow diminuendo, and by the end of the piece, it is silenced. At the same time, the background noise track becomes louder and peaks in the middle, interfering with and working alongside the voice. The track of synthesized frequencies slowly crescendos so that it is loudest at the end of the piece.

By distributing the volumes in this chiasmatic way, I want to call attention to the layered listenings happening within the situation of Mayer’s reading. Just as the figure of voice arises out of the ground of noise, it also contains frequencies that are not so easily differentiated from their background. A voice is an acoustic entity figured by a body and a performance. However habitual and repetitive the action is, it takes effort to suture vocal sounds to the body, place, and apparatus that they emanate from. In this track I want to find a way to hear a drifting, unconscious meandering within that focused effort. I want to materialize listening’s paratactic wavering of attention to one thing after another.

In the production of this movement toward noise, I value illegibility over legibility and the abstract over the figured. If we deemphasize voice, we acknowledge the ways in which voices can undo themselves in their production—which is the ethics of dream life that Mayer argues for and illuminates within her poem. The outside within the voice is a frequency scatter that connects the dissipation of an emitted sound in space with all the other sounds that interfere or resonate with that sound. The strange whisper music that ends my audio project “flattens” the sonic space idealized by the division of figure and ground. By abstracting Bernadette Mayer’s performance, I seek a synthesis that brings the noisy dream life of voice into relief.

_

Featured Image: “Scream” by Flickr user Josh Otis CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

_

John Melillo is an assistant professor in the English Department at the University of Arizona. His book project, Outside In: The Poetics of Noise from Dada to Punk, examines the ways in which poetry and performance make noise during the twentieth century. He has written and presented work on empathy in sound poetry, folk-song utopianism, the post-punk band DNA, and tape noise in Charles Olson. John performs music and sound art as Algae & Tentacles.

_

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Instrumental: Power, Voice, and Labor at the Airport – Asa Mendelsohn

“Don’t Be Self-Conchas:” Listening to Mexican Styled Phonetics in Popular Culture – Sara Veronica Hinijos

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice – Yvon Bonenfant

Instrumental: Power, Voice, and Labor at the Airport

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? Artist Asa Mendelsohn opens the forum with his critical and artistic work on the voice as an instrument of power. We are also honored that he lent Voices Carry a still from his work for our icon!–Jennifer Stoever

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? Artist Asa Mendelsohn opens the forum with his critical and artistic work on the voice as an instrument of power. We are also honored that he lent Voices Carry a still from his work for our icon!–Jennifer Stoever

important, critical, foundational

Can we all do something about language here, and the frames that we use? […] We need to…stop already pre-redacting ourselves so that we can be quote ‘heard’ by these jackasses! They’re never gonna listen to us! — Mariame Kaba

Instrumental is a body of work featuring a series of vocal performances by airport security workers I filmed at the San Diego International Airport. The work takes up Mariame Kaba’s provocation, that those currently in power are never going to listen. How might relations of power be reordered around a voice? If voices are instruments, operating at once through a body and as a body, what kind of instrument is a voice of authority?

T

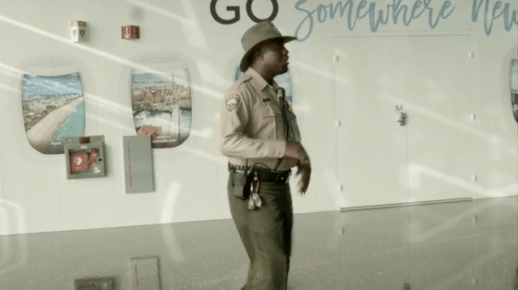

In September 2017, my proposal to produce a version of this project is accepted as part of a yearlong program curated by and for the San Diego International Airport. In October I put out a call for participation to airport security workers, in search of singers to perform songs of their choosing in front of a camera. There are emails with curators and security managers, logistics, parameters. I film over the winter and install a version of the work as a public art project in the spring, the first year of my medical gender transition.

When we meet at the far end of Terminal 2 in January, T is a combination of nervous and enthusiastic I wasn’t expecting. He’s so jittery that I almost tell him to stop and rest. I link my sneaking feeling of shame to an assumed position of authority, having arrived like this, multiple cameras, my university affiliation.

But while nervous, T’s also brimming, lighting up. His name tag catches gold light, bouncing against his gray Air Traffic Officer uniform.

T proposes two songs. Neither are in languages that he speaks in his daily life and he keeps forgetting words.

How am I going to forget you?

T says he learned the song from a former partner. He says girlfriend. He says he always felt self-conscious he couldn’t speak more Spanish. I guess that his family are Afro-Caribbean Spanish-speakers. I’m wrong. He’s also wrong about where I’m from. San Francisco, right?

T likes to sing karaoke. A coworker heard him and the rumor started going around: T has a beautiful voice. T’s voice is a soft instrument. In the airport, it is easily swallowed by environmental noise.

I film with T a second time, again meeting the last two hours of his ten-hour shift. He starts tired, nervous: stopping and restarting a song. Slowly, he warms up, dancing a cumbia. I sing with him when he forgets a line. We allow ourselves to take up more space in this quiet zone beyond the Air Canada counters. T dances with a moving chair.

Where will your next adventure take you?

Men in construction vests come in and out of a door beneath a banner: “Go Somewhere.” Construction is in process to expand the space occupied by border security.

Working in security means exercising jurisdiction over how other people move, who can move where, and with what freedom. What kind of freedom or movement is possible between us while someone is watching (an institution, a camera)?

Artist Gregg Bordowitz writes that “posing for the camera in advance of anticipated capture by the lens is a form of self-defense in the age of surveillance. It’s an act of self-authorship.” I don’t feel I understand fully what calls someone forward to perform. Is it a feeling they have something to share, a will towards “self-authorship”? I’m interested in not knowing where a performance starts and ends, not knowing when we become performers or our own authors, when we become complicit, exploited, when we are on or off the job. Most people work and are watched most of the time, without being heard: a series of performances delivered and received with varying degrees of care.

The sterile zone

The post-9/11 commercial airport in the United States is one among other types of places designed to reinforce a culture of surveillance and fear, to remind travelers the state has a say in their freedom of movement. A place designed to instill one kind of horror while thinly concealing another.

Spending time at the airport with people who spend a lot of time at the airport, the intricacy of the place unfolds, resembling what theorist Simone Browne calls a “security theater.” At moments SAN blurs into every other airport in the U.S. I’ve moved through or seen on a screen: streams of moving walkways, escalators — travelers wheeling bags, waiting, scrolling for ticket information on smartphones, scanning, travel-themed advertisements and watery public art commissions — a fragmented, moving stage.

From Asa Mendelsohn, Instrumental (2018)

The voice of the overhead announcement is an instrument of the airport security theater, summoning the stress of being read and misread, abused, glibly entertained, and sold overpriced breakfasts, while you are also in fear of missing something: everything that makes airports ultimate theaters for the machinery of the security state. As I edit footage from the airport, I become preoccupied by moments of tension between a singer’s voice and the voice of the overhead security announcement, instructing us about checkpoint procedures, orienting us, interpellating. A singer pauses to wait, or they continue, enduring the interruption. For a security worker vocalizing in uniform, does the space of the airport become an extension of their body? (Does their uniform matter?) In these moments of tension, it becomes more clear that a security worker’s performance as an extension of the airport’s body is an uneven one.

While SAN seems like any other airport in the U.S., there are points of exceptionality. SAN is much smaller than other airports serving international commercial flights. It is located centrally, widely accessible from much of the city. Checkpoint lines are rarely very long. SAN is, of course, primarily the port of entry for travelers with valid state identification and the ability to buy an airline ticket. These factors do not make SAN an equitable place to work, but they do add up to an effect: airport as sanitized space, a clean space, that, in my subjective experience, other airports aspire to but rarely achieve. A small feat of whitewashing, eighteen miles by car from the border crossing at San Ysidro. Friends have suggested about this project: “you would not have been able to do that anywhere else.” I would not have been granted access.

As I prepare to film at SAN, I’m sent mixed messages. Initially, a curator tells me I’ll be granted access to shoot in post-checkpoint areas of the airport, areas I learn that security workers call “the sterile zone.” Shortly before my first shoot, I’m told that, actually, it’d be too much work to get me clearance. I’m restricted to what are called “public” spaces, pre-security, outside the sterile zone.

From Asa Mendelsohn, Instrumental (2018)

Throughout this process, I wonder how I’m seen by people at the airport. I do not doubt that being white, small-bodied, and soft-voiced make me seem non-threatening. I’m a patient director. I smile at my own perversity. Staff approach me cautiously while I’m setting up and ask if I have a permit to be there, but always eventually smile back. A curator overlooks or disregards my pronouns, misgendering me in email correspondences and later in the interpretive text about the work. They eventually apologize.

How are my interests as an artist read? While “speaking up,” or “using your voice,” is often understood as a political right and responsibility of democratic process, appropriating someone else’s is at particular stake in art and documentary ethics. At the airport, I am seeking a form through which to acknowledge the ways we use each other’s voices and labor, to acknowledge the multiple zones within which we work at once.

Instrumentalized: used

A voice is always a shape and product of its body, and, at the same time, something other. Theorist Freya Jarman-Ivens writes: “As my voice leaves me, it takes part of my body with it — the sound of its own production.” The voice in your head that you claim as your own is never, physically, the same voice as that which lands in the ear of another, that you also claim as your own, as when you claim on the phone “it’s me.” Jarman-Ivens names this paradoxical, “looped” quality of the voice its “queerness,” traveling between bodies and between language and non- language.

Increasingly, state terrorism marks the airport as a space in which people are alienated on the basis of identity. The anxiety that comes while waiting in line for your body to be scanned epitomizes that alienation. The invasive acts of being scanned, read and misread, are not one-way operations. Security personnel, particularly those whose classed, raced, and gendered bodies straddle multiple identifications and categories of oppression, occupy a tense space: at once agents of the security apparatus and subjects within it.

At the airport I am trying to represent realities in which a speaker’s voice changes and morphs with and through their body and environment. Through collaborations with non-professional actors — with people performing as versions of themselves — I am hoping to communicate the slip and stutter between performance and real life that José Esteban Muñoz might describe as “failure,” or an “active political refusal.” “Failure” is, as I understand Muñoz’s writing and legacy, an opening into another space of relating, a break from performative norms, from a performance of a norm, such as “real life,” or “gender.” Does the performance start when a security worker starts singing? When they become the airport? A worker? When they become a man?

Featured image still from Asa Mendelsohn’s Instrumental.

—

Asa Mendelsohn is from New York. He makes performances and media projects that develop through a process of recording, writing, and collaboration. His work combines observational and narrative storytelling practices, often focusing on personal relationships and desire as ways to navigate seemingly inaccessible infrastructures, histories, and systems of power.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Unlearning Black Sound in Black Artistry: Examining the Quiet in Solange’s A Seat At the Table–Kimberly Williams

“Listening to the Border: ‘”2487″: Giving Voice in Diaspora’ and the Sound Art of Luz María Sánchez”-D. Ines Casillas

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice– Yvon Bonenfant

Recent Comments