You Got Me Feelin’ Emotions: Singing Like Mariah

Mariah Carey’s New Year’s Eve 2016 didn’t go so well. The pop diva graced a stage in the middle of Times Square as the clock ticked down to 2017 on Dick Clark’s Rockin New Year’s Eve, hosted by Ryan Seacrest. After Carey’s melismatic rendition of “Auld Lang Syne,” the instrumental for “Emotions” kicked in and Carey, instead of singing, informed viewers that she couldn’t hear anything. What followed was five minutes of heartburn. Carey strutted across the stage, hitting all her marks along with her dancers but barely singing. She took a stab at a phrase here and there, mostly on pitch, unable to be sure. And she narrated the whole thing, clearly perturbed to be hung out to dry on such a cold night with millions watching. I imagine if we asked Carey about her producer after the show, we’d get a “I don’t know her.”

These things happen. Ashlee Simpson’s singing career, such as it was, screeched to a halt in 2004 on the stage of Saturday Night Live when the wrong backing track cued. Even Queen Bey herself had to deal with lip syncing outrage after using a backing track at former President Barack Obama’s second inauguration. So the reaction to Carey, replete with schadenfreude and metaphorical pearl-clutching, was unsurprising, if also entirely inane. (The New York Times suggested that Carey forgot the lyrics to “Emotions,” an occurrence that would be slightly more outlandish than if she forgot how to breathe, considering it’s one of her most popular tracks). But yeah, this happens: singers—especially singers in the cold—use backing tracks. I’m not filming a “leave Mariah alone!!” video, but there’s really nothing salacious in this performance. The reason I’m circling around Mariah Carey’s frosty New Year’s Eve performance is because it highlights an idea I’m thinking about—what I’m calling the “produced voice” —as well as some of the details that are a subset of that idea; namely, all voices are produced.

I mean “produced” in a couple of ways. One is the Judith Butler way: voices, like gender (and, importantly, in tandem with gender), are performed and constructed. What does my natural voice sound like? I dunno. AO Roberts underlines this in a 2015 Sounding Out! post: “we’ll never really know how we sound,” but we’ll know that social constructions of gender helped shape that sound. Race, too. And class. Cultural norms make physical impacts on us, perhaps in the particular curve of our spines as we learn to show raced or gendered deference or dominance, perhaps in the texture of our hands as we perform classed labor, or perhaps in the stress we apply to our vocal cords as we learn to sound in appropriately gendered frequency ranges or at appropriately raced volumes. That cultural norms literally shape our bodies is an important assumption that informs my approach to the “produced voice.” In this sense, the passive construction of my statement “all voices are produced” matters; we may play an active role in vibrating our vocal cords, but there are social and cultural forces that we don’t control acting on the sounds from those vocal cords at the same moment.

Another way I mean that all voices are produced is that all recorded singing voices are shaped by studio production. This can take a few different forms, ranging from obvious to subtle. In the Migos song “T-Shirt,” Quavo’s voice is run through pitch-correction software so that the last word of each line of his verse (ie, the rhyming words: “five,” “five,” “eyes,” “alive”) takes on an obvious robotic quality colloquially known as the AutoTune effect. Quavo (and T-Pain and Kanye and Future and all the other rappers and crooners who have employed this effect over the years) isn’t trying to hide the production of his voice; it’s a behind-the-glass technique, but that glass is transparent. Less obvious is the way a voice like Adele’s is processed. Because Adele’s entire persona is built around the natural power of her voice, any studio production applied to it—like, say, the cavernous reverb and delay on “Hello” —must land in a sweet spot that enhances the perceived naturalness of her voice.

Vocal production can also hinge on how other instruments in a mix are processed. Take Remy Ma’s recent diss of Nicki Minaj, “ShETHER.” “ShETHER”’s instrumental, which is a re-performance of Nas’s “Ether,” draws attention to the lower end of Remy’s voice. “Ether” and “ShETHER” are pitched in identical keys and Nas’s vocals fall in the same range as Remy’s. But the synth that bangs out the looping chord progression in “ShETHER” is slightly brighter than the one on “Ether,” with a metallic, digital high end the original lacks. At the same time, the bass that marks the downbeat of each measure is quieter in “ShETHER” than it is in “Ether.” The overall effect, with less instrumental occupying “ShETHER”’s low frequency range and more digital overtones hanging in the high frequency range, causes Remy Ma’s voice to seem lower, manlier, than Nas’s voice because of the space cleared for her vocals in the mix. The perceived depth of Remy’s produced voice toys with the hypermasculine nature of hip hop beefs, and queers perhaps the most famous diss track in the genre. While engineers apply production effects directly to the vocal tracks of Quavo and Adele to make them sound like a robot or a power diva, the Remy Ma example demonstrates how gender play can be produced through a voice by processing what happens around the vocals.

Let’s return to Times Square last New Year’s Eve to consider the produced voice in a hybrid live/recorded setting. Carey’s first and third songs “Auld Lang Syne” and “We Belong Together”) were entirely back-tracked—meaning the audience could hear a recorded Mariah Carey even if the Mariah Carey moving around on our screen wasn’t producing any (sung) vocals. The second, “Emotions,” had only some background vocals and the ridiculously high notes that young Mariah Carey was known for. So, had the show gone to plan, the audience would’ve heard on-stage Mariah Carey singing along with pre-recorded studio Mariah Carey on the first and third songs, while on-stage Mariah Carey would’ve sung the second song entirely, only passing the mic to a much younger studio version of herself when she needed to hit some notes that her body can’t always, well, produce anymore. And had the show gone to plan, most members of the audience wouldn’t have known the difference between on-stage and pre-recorded Mariah Carey. It would’ve been a seamless production. Since nothing really went to plan (unless, you know, you’re into some level of conspiracy theory that involves self-sabotage for the purpose of trending on Twitter for a while), we were all privy to a component of vocal production—the backing track that aids a live singer—that is often meant to go undetected.

The produced-ness of Mariah Carey’s voice is compelling precisely because of her tremendous singing talent, and this is where we circle back around to Butler. If I were to start in a different place–if I were, in fact, to write something like, “Y’all, you’ll never believe this, but Britney Spears’s singing voice is the result of a good deal of studio intervention”–well, we wouldn’t be dealing with many blown minds from that one, would we? Spears’s career isn’t built around vocal prowess, and she often explores robotic effects that, as with Quavo and other rappers, make the technological intervention on her voice easy to hear. But Mariah Carey belongs to a class of singers—along with Adele, Christina Aguilera, Beyoncé, Ariana Grande—who are perceived to have naturally impressive voices, voices that aren’t produced so much as just sung. The Butler comparison would be to a person who seems to fit quite naturally into a gender category, the constructed nature of that gender performance passing nearly undetected. By focusing on Mariah Carey, I want to highlight that even the most impressive sung voices are produced, and that means that we can not only ask questions about the social and cultural impact of gender, race, class, ability, sexuality, and other norms may have on those voices, but also how any sung voice (from Mariah Carey’s to Quavo’s) is collaboratively produced—by singer, technician, producer, listener—in relation to those same norms.

Being able to ask those questions can get us to some pretty intriguing details. At the end of the third song, “We Belong Together,” she commented “It just don’t get any better” before abandoning the giant white feathers that were framing her onstage. After an awkward pause (during which I imagine Chris Tucker’s “Don’t cut to me!” face), the unflappable Ryan Seacrest noted, “No matter what Mariah does, the crowd absolutely loves it. You can’t go wrong with Ms. Carey, and those hits, those songs, everybody knows.” Everybody knows. We didn’t need to hear Mariah Carey sing “Emotions” that night because we could fill it all in–everybody knows that song. Wayne Marshall has written about listeners’ ability to fill in the low frequencies of songs even when we’re listening on lousy systems—like earbuds or cell phone speakers—that can’t really carry it to our ears. In the moment of technological failure, whether because a listener’s speakers are terrible or a performer’s monitors are, listeners become performers. We heard what was supposed to be there, and we supplied the missing content.

Sound is intimate, a meeting of bodies vibrating in time with one another. Yvon Bonenfant, citing Stephen Connor’s idea of the “vocalic body,” notes this physicality of sound as a “vibratory field” that leaves a vocalizer and “voyages through space. Other people hear it. Other people feel it.” But in the case of “Emotions” on New Year’s Eve, I heard a voice that wasn’t there. It was Mariah Carey’s, her vocalic body sympathetically vibrated into being. The question that catches me here is this: what happens in these moments when a listener takes over as performer? In my case, I played the role of Mariah Carey for a moment. I was on my couch, surrounded by my family, but I felt a little colder, like I was maybe wearing a swimsuit in the middle of Times Square in December, and my heart rate ticked up a bit, like maybe I was kinda panicked about something going wrong, and I heard Mariah Carey’s voice—not, crucially, my voice singing Mariah Carey’s lyrics—singing in my head. I could feel my vocal cords compressing and stretching along with Carey’s voice in my head, as if her voice were coming from my body. Which, in fact it was—just not my throat—as this was a collaborative and intimate production, my body saying, “Hey, Mariah, I got this,” and performing “Emotions” when her body wasn’t.

By stressing the collaborative nature of the produced voice, I don’t intend to arrive at some “I am Mariah” moment that I could poignantly underline by changing my profile picture on Facebook. Rather, I’m thinking of ways someone else’s voice is could lodge itself in other bodies, turning listeners into collaborators too. The produced voice, ultimately, is a way to theorize unlikely combinations of voices and bodies.

—

Featured image: By all-systems-go at Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

—

Justin Adams Burton is Assistant Professor of Music at Rider University, and a regular writer at Sounding Out! You can catch him at justindburton.com.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Gendered Sonic Violence, from the Waiting Room to the Locker Room-Rebecca Lentjes

I Can’t Hear You Now, I’m Too Busy Listening: Social Conventions and Isolated Listening–Osvaldo Oyola

One Nation Under a Groove?: Music, Sonic Borders, and the Politics of Vibration-Marcus Boon

The Love Below (the Mason Dixon Line): OutKast’s Rejection at the 1995 Source Awards

During his acceptance speech at 2017’s Golden Globe awards, actor and rapper Donald “Childish Gambino” Glover thanked the black people of the city of Atlanta for “being alive,” and the Atlanta trap rap group Migos for their single “Bad and Boujee.” As the camera panned out into the crowd, it showed dominantly white faces full of confusion and polite yet uncomfortable laughter. These audience members seemed unfamiliar with Migos and with categorizing a “black” Atlanta (and South) separate from the pop culture hub we know as Atlanta today. Glover’s speech re-affirmed the sentiments of Outkast’s Andre “3000” Benjamin over twenty years’ prior at the 1995 Source Awards, that the (black) South got something to say.

As I’ve argued previously, Andre and Big Boi’s acceptance speech at the Source Awards was the springboard for what I call the “hip hop south,” the social-cultural experiences that frame southern blackness after the Civil Rights Movement. The declaration “the South got something to say”—and the booing that ensued—is important to engaging how southerners see and hear themselves in a contemporary landscape. The Source Award’s dominantly New York audience booing both jolts the ear and affirms hip hop’s hyper-regional focus in the early to mid 1990s. The booing crowd identifies hip hop as northeastern, urban, and rigidly masculine, an aesthetic that was a daunting task for non-northeastern performers to try and break through. Even celebrated west coast artists like Snoop Dogg, who menacingly and repeatedly asked the crowd “you don’t love us?” during the show, struggled with the challenge of being recognized – and respected – by northeast hip hop enthusiasts.

The 1995 Source Awards proved to be the climax of the beef instigated by both West Coast Death Row Records and East Coast Bad Boy Records, the bitter lyrical and personal battle between Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., and OutKast, a Southern act, chosen as “Best New Rap Group.” The crowd’s increasingly despondent sonic rejection of hip hop outside of New York foregrounds my reading of OutKast’s acceptance speech as blatant and unforgiving southern black protest, a rallying cry that carves a space for the hip hop south to come into existence.

A recap of that night, in which Christopher “Kid” Reid and Salt-N-Pepa presented OutKast their award. Upbeat and playful, Kid says “ladies help me out” to announce the winner, but there is a distinctive drop in their enthusiasm when naming OutKast the winner of the category. The inflection in their voices signifies shock and even disappointment, with Kid quickly trying to be diplomatic by shouting out OutKast’s frequent collaborators and label mates Goodie Mob. The negative reaction from the crowd was immediate, with sharp and continuous booing.

Big Boi starts his acceptance speech, dropping a few colloquial words immediately recognizable as proper hip hop – “word” and “what’s up?” Over a growingly irritated crowd, Big Boi acknowledges that he is in New York, “y’alls city,” and tries to show respect to the New York rappers by crediting them as “original emcees.” Big Boi recognizes he is an outsider, his southern drawl long and clear in his pronunciation of “south” as “souf,” yet attempts to be diplomatic and respectful of New York. There is also a recognition that where he is from, Atlanta, is also a city: his statement, “y’alls city,” is not only a recognition of his being an outsider but a proclamation that he, too, comes from a city—except it’s a different city.

Big Boi’s embrace of Atlanta as urban challenges previous cultural narratives of southerners as incapable of maneuvering within an urban setting. Because of a long-standing and comfortable assumption that the American south was incapable of anything urban (i.e. mass transit, tall buildings, bustling neighborhoods and other forms of communities), beliefs about southerners’ perspectives remained aligned with rural – read ‘country’ and ‘backward’ – sensibilities incapable of functioning within an urban cultural setting. These sensibilities often played out in longhand form via literature or in popular black music, with focus on dialect and language standing in as a signifier of regional and cultural distinction.

Big Boi still repping ATL in 2012, Outside Lands Music Festival, San Francisco, CA, Image by Flickr User Thomas Hawk, (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Consider Rudolph Fisher’s southern protagonist King Solomon Gillis from the short story “City of Refuge” (1925). Fisher’s characterization of Gillis, a black man from rural North Carolina, is one of naiveté and awe for not only New York and its sounds, but the premise of city life in general. In the opening of the story Fisher describes Gillis’s ride on the subway as “terrifying,” with “strange and terrible sounds.” References to the bang and clank of the subway doors and the close proximity of each train as “distant thunder” is particularly striking, a subtle sonic nod to Gillis’ rural southernness and his inability to articulate the subway system outside of his limited southern experiences. The references to “heat,” “oppression,” and “suffocation” also lend premise to southern weather, a well as the belief of the American south as an unending repetition of slavery and its effects.

It is important to point out that Gillis certainly isn’t a fearful man in the literal sense: his reason for migrating to Harlem was out of necessity and desperation after shooting a white man back home to avoid being lynched. Yet Fisher’s attention to sound presents Gillis as an outsider. Further, Fisher describes Gillis as “Jonah emerging from the whale,” both a biblical allusion to triumph over a difficult situation as well as a rebirth, the possibility of a new life and new purpose. This can be connected to the biblical reckoning of southern black folks migrating out of the south for social-economic change and advancement.

Still, southern black folks emerging in the city is not an easy transition, with Gillis’ train ride and his discomfort with the sounds it produces symbolizing the move from one difficult landscape to another. Although Gillis ultimately is confronted with the brutality he was trying to avoid in North Carolina, his repetitive proclamation, “they even got cullud policemans!” amplified his southernness and naiveté. Fisher’s intentional use of written dialect enhances the repetitiveness of the impact of seeing black police officers, which blots out the characteristic of region but not white supremacy as a whole. Gillis’s acceptance of black police officers blurred the binaries of the Great Migration as a testament to black folks not only looking for social-economic change outside of the American South, a terroristic space for blacks, but the unfortunate anxiety of those deciding to remain in the south, complacent in the lack of social equality.

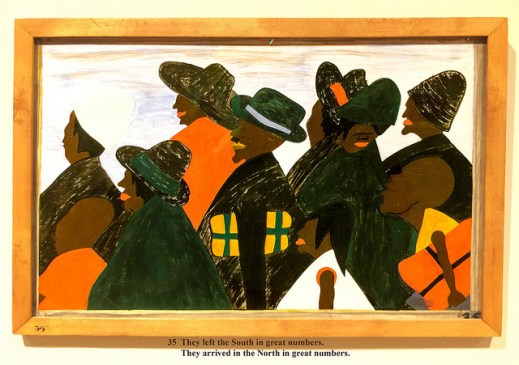

Panel 35 of Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, documenting Black Americans’ move to Northern Urban Centers : “They Left the South in Great Numbers. They Arrived in the North in Great Numbers.” Photo by Flickr User Ron Cogswell, (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Seventy years later Big Boi, a Georgian, returns to New York with the confidence of both rural and southern sensibilities outside of the immediately recognizable urban trope embodied by New York. Big Boi’s full embrace of being “cullud,” in both the linguistic and cultural elements that Fisher’s long-hand dialect represented as authentic southernness, is jarring because his intentional embrace of southern blackness as othered anchors his approach to rap music. Big Boi does not posture the south as a space or place in need of escape or reposturing. Rather, the hyper-awareness from both Big Boi and Andre in front of the dominantly New York crowd ruptures the accepted narrative of the south as needing saving by non-southern counterparts. Big Boi’s speech forces the audience to de-romanticize their notions of northeastern supremacy and recognize the south as capable of hip hop. Their direct booing is a sonic representation of that discomfort.

From this perspective, André’s now iconic remarks from the acceptance speech further emphasized Big Boi’s departure from reckoning with northeastern hip hop as the standard. He stumbles in his speech, possibly because of nerves or irritation, and, like Big Boi, must talk over the crowd. André speaks about having the “demo tape and don’t nobody wanna hear it,” a double signifier of not only being rejected for his southernness but also the difficulty of breaking into the music industry. André’s frustration with being unheard as a southerner can also be extended into the actual production of the tape by OutKast’s production team Organized Noize, who drew from southern musical influences like funk, blues, and gospel to ground their beats. Andre’s call-to-arms, “the south got something to say,” rallied other southern rappers to self-validate their own music. It is important to note that André’s rally called to the entire south, not just Atlanta. This is significant in thinking about southern experiences as non-monolithic, the aural-cultural possibilities of multiple Souths and their various intersections using hip hop aesthetics.

OutKast at the Pemberton Music Festival, CREDIT MARK C AUSTIN(CC BY 2.0)

OutKast moves past their rejection at the Source Awards via their second album ATLiens (Atlanta aliens), which offered an equal rejection of hip hop culture’s binaries. The album’s use of ‘otherworldly’ sonic signifiers i.e. synthesizers and pockets of silence that sounded like space travel – embodied their deliberate isolation from mainstream hip hop culture. Still, OutKast didn’t forget their rejection, sampling their acceptance speech in the final track from their third album Aquemini titled “Chonkyfire.” The brazen and hazy riffs of an electric guitar guide the song, with the recording from the source appearing at the end of the track. There is a deliberate slowing down of the track, with both the accompaniment and the recording becoming increasingly muddled. After André’s declaration “the south got something to say,” the track begins to crawl to its end, a sonic signifier of not only the end of the album but also the end of OutKast’s concern with bi-coastal hip hop expectations. Sampling their denial at the Source Awards was a full-circle moment for their music and identities. It was a reminder that the South was a legitimate hip hop cultural space.

In this contemporary moment, there is less focus and interest in establishing regional identities in hip hop. The dominance of social media collapses a specific need to carve up hip hop spaces per physical parameters. Sonically, there is an intriguing phenomenon occurring where rappers from across the country are borrowing from southern hip hop aesthetics, whether it be the drawl, bass kicks, or lyrical performance. Although our focus on social media has seemingly collapsed the physical need to differentiate region and identity, geographical aesthethics remain central to our listening practices. With this in mind, OutKast’s initial rejection from then mainstream hip hop in favor of sonic and cultural reckonings of southern blackness keep them central to conversations about how the Hip Hop South continues to ebb and weave within and outside the parameters of hip hop culture. Their rejection of hip hop’s stage solidified their place on it.

—

Featured Image “Big Boi I” by Flickr user Matt Perich (CC BY 2.0)

—

Regina N. Bradley, Ph.D is an instructor of English and Interdisciplinary Studies at Kennesaw State University. She earned her Ph.D in African American Literature at Florida State University in 2013. Regina writes about post-Civil Rights African American literature, the contemporary U.S. South, pop culture, race and sound, and Hip Hop. Her current book project explores how critical hip hop (culture) sensibilities can be used to navigate race and identity politics in this supposedly postracial moment of American history. Also known as Red Clay Scholar, a nod to her Georgia upbringing, Regina maintains a blog and personal website and can also be reached on Twitter at @redclayscholar.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Caterpillars and Concrete Roses in a Mad City: Kendrick Lamar’s “Mortal Man” Interview with Tupac Shakur—Regina Bradley

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity — Regina Bradley

The (Magic) Upper Room: Sonic Pleasure Politics in Southern Hip Hop—Regina Bradley

Recent Comments