The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2018!

For your end-of-the year reading pleasure, here are the Top Ten Posts of 2018 (according to views as of 12/4/18). Visit this brilliance today–and often!–and know more fire is coming in 2019!

***

J. Martin Vest

In the early 1870s a talking machine, contrived by the aptly-named Joseph Faber appeared before audiences in the United States. Dubbed the “talking head” by its inventor, it did not merely record the spoken word and then reproduce it, but actually synthesized speech mechanically. It featured a fantastically complex pneumatic system in which air was pushed by a bellows through a replica of the human speech apparatus, which included a mouth cavity, tongue, palate, jaw and cheeks. To control the machine’s articulation, all of these components were hooked up to a keyboard with seventeen keys— sixteen for various phonemes and one to control the Euphonia’s artificial glottis. Interestingly, the machine’s handler had taken one more step in readying it for the stage, affixing to its front a mannequin. Its audiences in the 1870s found themselves in front of a machine disguised to look like a white European woman.[. . .Click here to read more!]

9).Mixtapes v. Playlists: Medium, Message, Materiality

Mike Glennon

The term mixtape most commonly refers to homemade cassette compilations of music created by individuals for their own listening pleasure or that of friends and loved ones. The practice which rose to widespread prominence in the 1980s often has deeply personal connotations and is frequently associated with attempts to woo a prospective partner (romantic or otherwise). As Dean Wareham, of the band Galaxie 500 states, in Thurston Moore’s Mix-Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture, “it takes time and effort to put a mix tape together. The time spent implies an emotional connection with the recipient. It might be a desire to go to bed, or to share ideas. The message of the tape might be: I love you. I think about you all the time. Listen to how I feel about you” (28).

Alongside this ‘private’ history of the mixtape there exists a more public manifestation of the form where artists, most prominently within hip-hop, have utilised the mixtape format to the extent that it becomes a genre, akin to but distinct from the LP. As Andrew “Fig” Figueroa has previously noted here in SO!, the mixtape has remained a constant component of Hip Hop culture, frequently constituting, “a rapper’s first attempt to show the world their skills and who they are, more often than not, performing original lyrics over sampled/borrowed instrumentals that complement their style and vision.” From the early mixtapes of DJs such as Grandmaster Flash in the late ’70s and early ’80s, to those of DJ Screw in the ’90s and contemporary artists such as Kendrick Lamar, the hip-hop mixtape has morphed across media, from cassette to CDR to digital, but has remained a platform via which the sound and message of artists are recorded, copied, distributed and disseminated independent of the networks and mechanics of the music and entertainment industries. In this context mixtapes offer, as Paul Hegarty states in his essay, The Hallucinatory Life of Tapes (2007), “a way around the culture industry, a re-appropriation of the means of production.” [. . .Click here for more!]

8).My Music and My Message is Powerful: It Shouldn’t be Florence Price or “Nothing”

Samantha Ege

Flashback to the second day of the recent Gender Diversity in Music Making Conference in Melbourne, Australia (6-8 July 2018). In a few hours, I will perform the first movement of the Sonata in E minor for piano by Florence Price(1887–1953). In the lead-up, I wonder whether Price’s music has ever been performed in Australia before, and feel honored to bring her voice to new audiences. I am immersed in the loop of my pre-performance mantra:

My music and message is powerful, my music and message is powerful.

Repeating this phrase helps me to center my purpose on amplifying the voice of a practitioner who, despite being the first African-American woman composer to achieve national and international success, faced discrimination throughout her life, and even posthumously in the recognition of her legacy.

In Price’s time, there were those in positions of privilege and power who listened to her music and gave her a platform. One such instance was Frederick Stock of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and his 1933 premier of her Symphony in E minor. But there were times when her musical scores were met with silence. For example, when she wrote to Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony Orchestra requesting that he hear her music, the letter remained unanswered. There was a notable intermittency in how Price was heard, which continues today. It seems most natural for mainstream platforms to amplify her voice in months dedicated to women and Black history; any other time of the year appears to require more justification. And so, as I am repeating this mantra—my music and message is powerful—I am attempting to de-centre my anxieties, and center my service to amplifying Price’s voice through an assured performance . [. . .Click here for more!]

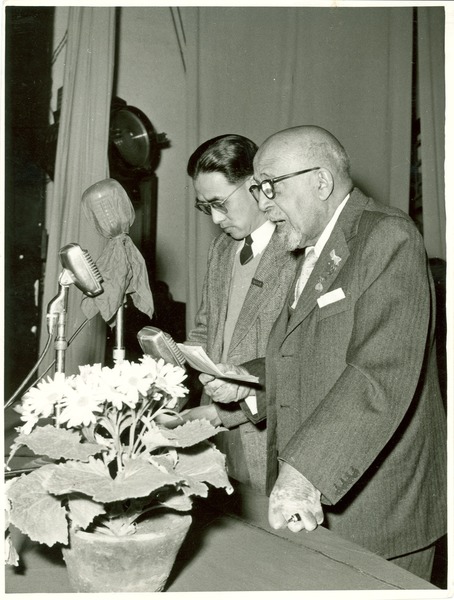

7). “Most pleasant to the ear”: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Itinerant Intellectual Soundscapes

Phillip Sinitiere

Upon completing a Ph.D. in history at Harvard in 1895, and thereafter working as a professor, author, and activist for the duration of his career until his death in 1963, Du Bois spent several months each year on lecture trips across the United States. As biographers and Du Bois scholars such as Nahum Chandler, David Levering Lewis, and Shawn Leigh Alexander document, international excursions to Japan in the 1930s included public speeches. Du Bois also lectured in China during a global tour he took in the late 1950s.

In his biographical writings, Lewis describes the “clipped tones” of Du Bois’s voice and the “clipped diction” in which he communicated, references to the accent acquired from his New England upbringing in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Reporter Cedric Belfrage, editor of the National Guardian for which Du Bois wrote between the 1940s and 1960s, listened to the black scholar speak at numerous Guardian fundraisers. “On each occasion he said just what needed saying, without equivocation and with extraordinary eloquence,” Belfrage described. “The timbre of his public-address voice was as thrilling in its way as that of Robeson’s singing voice. He wrote and spoke like an Old Testament prophet.” George B. Murphy heard Du Bois speak when he was a high school student and later as a reporter in the 1950s; he recalled the “crisp, precise English of [Du Bois’s] finely modulated voice.” [. . .Click here for more]

6.) Beyond the Grave: The “Dies Irae” in Video Game Music

Karen Cook

For those familiar with modern media, there are a number of short musical phrases that immediately trigger a particular emotional response. Think, for example, of the two-note theme that denotes the shark in Jaws, and see if you become just a little more tense or nervous. So too with the stabbing shriek of the violins from Psycho, or even the whirling four-note theme from The Twilight Zone. In each of these cases, the musical theme is short, memorable, and unalterably linked to one specific feeling: fear.

The first few notes of the “Dies Irae” chant, perhaps as recognizable as any of the other themes I mentioned already, are often used to provoke that same emotion. [. . .Click here for more!]

5). Look Away and Listen: The Audiovisual Litany in Philosophy

Robin James

According to sound studies scholar Jonathan Sterne in The Audible Past, many philosophers practice an “audiovisual litany,” which is a conceptual gesture that favorably opposes sound and sonic phenomena to a supposedly occularcentric status quo. He states, “the audiovisual litany…idealizes hearing (and, by extension, speech) as manifesting a kind of pure interiority. It alternately denigrates and elevates vision: as a fallen sense, vision takes us out of the world. But it also bathes us in the clear light of reason” (15). In other words, Western culture is occularcentric, but the gaze is bad, so luckily sound and listening fix all that’s bad about it. It can seem like the audiovisual litany is everywhere these days: from Adriana Cavarero’s politics of vocal resonance, to Karen Barad’s diffraction, to, well, a ton of Deleuze-inspired scholarship from thinkers as diverse as Elizabeth Grosz and Steve Goodman, philosophers use some variation on the idea of acoustic resonance (as in, oscillatory patterns of variable pressure that interact via phase relationships) to mark their departure from European philosophy’s traditional models of abstraction, which are visual and verbal, and to overcome the skeptical melancholy that results from them. The field of philosophy seems to argue that we need to replace traditional models of philosophical abstraction, which are usually based on words or images, with sound-based models, but this argument reproduces hegemonic ideas about sight and sound. [. . .Click here to read more!]

4). becoming a sound artist: analytic and creative perspectives

Rajna Swaminathan

Recently, in a Harvard graduate seminar with visiting composer-scholar George Lewis, the eminent professor asked me pointedly if I considered myself a “sound artist.” Finding myself put on the spot in a room mostly populated with white male colleagues who were New Music composers, I paused and wondered whether I had the right to identify that way. Despite having exploded many conventions through my precarious membership in New York’s improvised/creative music scene, and through my shift from identifying as a “mrudangam artist” to calling myself an “improviser,” and even, begrudgingly, a “composer” — somehow “sound artist” seemed a bit far-fetched. As I sat in the seminar, buckling under the pressure of how my colleagues probably defined sound art, Prof. Lewis gently urged me to ask: How would it change things if I did call myself a sound artist? Rather than imposing the limitations of sound art as a genre, he was inviting me to reframe my existing aesthetic intentions, assumptions, and practices by focusing on sound.

Sound art and its offshoots have their own unspoken codes and politics of membership, which is partly what Prof. Lewis was trying to expose in that teaching moment. However, for now I’ll leave aside these pragmatic obstacles — while remaining keenly aware that the question of who gets to be a sound artist is not too distant from the question of who gets to be an artist, and what counts as art. For my own analytic and creative curiosity, I would like to strip sound art down to its fundamentals: an offering of resonance or vibration, in the context of a community that might find something familiar, of aesthetic value, or socially cohesive, in the gestures and sonorities presented. [. . .Click here for more!]

Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr.

How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House? –DJ Irene

At the Arena Nightclub in Hollywood, California, the sounds of DJ Irene could be heard on any given Friday in the 1990s. Arena, a 4000-foot former ice factory, was a haven for club kids, ravers, rebels, kids from LA exurbs, youth of color, and drag queens throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The now-defunct nightclub was one of my hang outs when I was coming of age. Like other Latinx youth who came into their own at Arena, I remember fondly the fashion, the music, the drama, and the freedom. It was a home away from home. Many of us were underage, and this was one of the only clubs that would let us in.

Arena was a cacophony of sounds that were part of the multi-sensorial experience of going to the club. There would be deep house or hip-hop music blasting from the cars in the parking lot, and then, once inside: the stomping of feet, the sirens, the whistles, the Arena clap—when dancers would clap fast and in unison—and of course the remixes and the shout outs and laughter of DJ Irene, particularly her trademark call and response: “How Many Motherfucking Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?,” immortalized now on CDs and You-Tube videos.

Irene M. Gutierrez, famously known as DJ Irene, is one of the most successful queer Latina DJs and she was a staple at Arena. Growing up in Montebello, a city in the southeast region of LA county, Irene overcame a difficult childhood, homelessness, and addiction to break through a male-dominated industry and become an award-winning, internationally-known DJ. A single mother who started her career at Circus and then Arena, Irene was named as one of the “twenty greatest gay DJs of all time” by THUMP in 2014, along with Chicago house music godfather, Frankie Knuckles. Since her Arena days, DJ Irene has performed all over the world and has returned to school and received a master’s degree. In addition to continuing to DJ festivals and clubs, she is currently a music instructor at various colleges in Los Angeles. Speaking to her relevance, Nightclub&Bar music industry website reports, “her DJ and life dramas played out publicly on the dance floor and through her performing. This only made people love her more and helped her to see how she could give back by leading a positive life through music.” [. . .Click here for more!]

2). Canonization and the Color of Sound Studies

Budhaditya Chattopadhyay

Last December, a renowned sound scholar unexpectedly trolled one of my Facebook posts. In this post I shared a link to my recently published article “Beyond Matter: Object-disoriented Sound Art (2017)”, an original piece rereading of sound art history. With an undocumented charge, the scholar attacked me personally and made a public accusation that I have misinterpreted his work in a few citations. I have followed this much-admired scholar’s work, but I never met him personally. As I closely read and investigated the concerned citations, I found that the three minor occasions when I have cited his work neither aimed at misrepresenting his work (there was little chance), nor were they part of the primary argument and discourse I was developing.

What made him react so abruptly? I have enjoyed reading his work during my research and my way of dealing with him has been respectful, but why couldn’t he respect me in return? Why couldn’t he engage with me in a scholarly manner within the context of a conversation rather than making a thoughtless comment in public aiming to hurt my reputation?

Consider the social positioning. This scholar is a well-established white male senior academic, while I am a young and relatively unknown researcher with a non-white, non-European background, entering an arena of sound studies which is yet closely guarded by the Western, predominantly white, male academics. This social divide cannot be ignored in finding reasons for his outburst. I immediately sensed condescension and entitlement in his behavior. [. . .Click here for more!]

1). Botanical Rhythms: A Field Guide to Plant Music

Carlo Patrão

Only overhead the sweet nightingale

Ever sang more sweet as the day might fail,

And snatches of its Elysian chant

Were mixed with the dreams of the Sensitive Plant

Percy Shelley, The Sensitive Plant, 1820

ROOT: Sounds from the Invisible Plant

Plants are the most abundant life form visible to us. Despite their ubiquitous presence, most of the times we still fail to notice them. The botanists James Wandersee and Elizabeth Schussler call it “plant blindness, an extremely prevalent condition characterized by the inability to see or notice the plants in one’s immediate environment. Mathew Hall, author of Plants as Persons, argues that our neglect towards plant life is partly influenced by the drive in Western thought towards separation, exclusion, and hierarchy. Our bias towards animals, or zoochauvinism–in particular toward large mammals with forward facing eyes–has been shown to have negative implications on funding towards plant conservation. Plants are as threatened as mammals according to Kew’s global assessment of the status of plant life known to science. Curriculum reforms to increase plant representation and engaging students in active learning and contact with local flora are some of the suggested measures to counter our plant blindness.

Participatory art including plants might help dissipate plants’ invisibility. Some authors argue that meaningful experiences involving a multiplicity of senses can potentially engage emotional responses and concern towards plants life. In this article, I map out a brief history of the different musical and sound art practices that incorporate plants and discuss the ethics of plant life as a performative participant. [. . .Click here for more!]

—

Featured Image: “SO! stamp” by j. Stoever

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2017!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2016!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2015!

Blog-o-versary Podcast EPISODE 62: ¡¡¡¡RESIST!!!!

Mixtapes v. Playlists: Medium, Message, Materiality

The term mixtape most commonly refers to homemade cassette compilations of music created by individuals for their own listening pleasure or that of friends and loved ones. The practice which rose to widespread prominence in the 1980s often has deeply personal connotations and is frequently associated with attempts to woo a prospective partner (romantic or otherwise). As Dean Wareham, of the band Galaxie 500 states, in Thurston Moore’s Mix-Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture, “it takes time and effort to put a mix tape together. The time spent implies an emotional connection with the recipient. It might be a desire to go to bed, or to share ideas. The message of the tape might be: I love you. I think about you all the time. Listen to how I feel about you” (28).

Alongside this ‘private’ history of the mixtape there exists a more public manifestation of the form where artists, most prominently within hip-hop, have utilised the mixtape format to the extent that it becomes a genre, akin to but distinct from the LP. As Andrew “Fig” Figueroa has previously noted here in SO!, the mixtape has remained a constant component of Hip Hop culture, frequently constituting, “a rapper’s first attempt to show the world their skills and who they are, more often than not, performing original lyrics over sampled/borrowed instrumentals that complement their style and vision.” From the early mixtapes of DJs such as Grandmaster Flash in the late ’70s and early ’80s, to those of DJ Screw in the ’90s and contemporary artists such as Kendrick Lamar, the hip-hop mixtape has morphed across media, from cassette to CDR to digital, but has remained a platform via which the sound and message of artists are recorded, copied, distributed and disseminated independent of the networks and mechanics of the music and entertainment industries. In this context mixtapes offer, as Paul Hegarty states in his essay, The Hallucinatory Life of Tapes (2007), “a way around the culture industry, a re-appropriation of the means of production.”

More recently the mixtape has been touted by corporations such as Spotify and Apple as an antecedent to the curated playlists which have become an increasingly prominent factor within the contemporary music industry. Alongside this the cassette has reemerged as a format, predominantly for independent and experimental artists and labels. The mixtape has also reemerged as a creative form in experimental music practice – part composition, part compilation, this contemporary manifestation of the mixtape is located somewhere between sound art and the DJ mix.

image by Flickr user Grace Smith, (CC BY 2.0)

This article explores these current manifestations of the mixtape. It analyses Spotify’s curated playlists and identifies some of the worrying factors that emerge from the ‘playlistification’ of recorded music. It goes on to discuss contemporary cassette culture and the contemporary mixtape identifying a set of characteristics which warrant the use of the term “mixtape” and distinguish it from forms such as the playlist. These characteristics, I suggest, may be adopted as strategies to address some of the contemporary crises in how we create, distribute, listen to, and consume music.

Playlists

“Day 213: Mix Tape – The Lost Art Form” by Flickr User Juli, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The mixtape has been presented as something of a forerunner to the music industry’s current streaming and subscription model and, in particular, of the curated playlists which Spotify sees as its, “answer to product innovation.” For Kieran Fenby-Hulse, writing in Networked Music Cultures: Contemporary Approaches, Emerging Issues, “the mixtape’s aura has underpinned the development of music streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music” (174). Spotify’s corporate literature makes this connection explicitly via multiple references to mixtapes. The press release announcing the launch of its Discover Weekly playlist, for example, promises, “our best-ever recommendations delivered to you as a weekly mixtape of fresh music,” stating, “It’s like having your best friend make you a personalised mixtape every single week.”

Where the mixtape’s audience of one however, is the favoured other, friend, loved one, lover, Spotify’s curated and algorithmic playlists shift the focus inward. They are not created by someone for another, nor gifted to someone by another. They are created algorithmically for me and me alone. The promise of Spotify is that of “every playlist tuned just to you every single week.” Spotify delivers on this promise via its vast accumulation and exploitation of user data. The labour of the Spotify playlist thus is not the labour of love often associated with the mixtape, but rather it is an example of the increasingly prominent practice of corporations and service providers benefiting from unremunerated fan labour via, as Patrick Burkart notes in an essay entitled Music in the Cloud and the Digital Sublime , commodification of the “comments, playlists, recommendations, news, reviews, and behavioral profiles,” of music fans.

Analysis of Spotify For Brands’ corporate literature provides more insight into how Spotify utilises this data. Amongst millennials, for example, Spotify identifies “seven key audio streaming moments for marketers to tap into” – working, chilling, chores, gaming, partying and driving – and advises that “for marketers, this is a chance to reach millennials through a medium they trust and see as a positive enhancer or tool.” Spotify’s party playlists thus are an opportunity for brands to “think about enhancing the party moment by learning your audience’s favorite genres and subgenres and matching the beat” or “think audio for connected speakers and mobile display ads for that obsessive DJ always checking on their next song to further drive your message.” Spotify’s party playlists also seek to dispense with the unexpected juxtapositions and sonic clashes that have formed such a vital and valued component of DJ/sampling culture and the amateurism, imperfections, and crude edits of their supposed mixtape forebear. Thus ‘the mix,’ what Paul Miller (DJ Spooky) refers to as the process whereby “different voices and visions constantly collide and cross-fertilize one another” is replaced with promises of “professionally beat-matched music [where] every song blends smoothly with the next.” The hybrid of the mix thus is homogenised in the playlist.

In seeking to provide a music mix that is smooth, adaptable and perfectly transitioned, Spotify’s mood based playlists (“Your Coffee Break,” “Sad Songs,” “Songs To Sing In The Car”) are more closely aligned with the aura of Muzak and the Muzak Corporation than with that of the “mixtape” (a comparison previously made by Liz Pelly in her article The Problem with Muzak). The Muzak Corporation provided background music for the workplace from the 1920s and public spaces such as hotel elevators and shopping malls from the 1940s onwards aiming, as Brandon Labelle states in Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture and Everyday Life, to provide “a form of environmental conditioning to aid in the general mood of the populace.” (173)

Spotify’s promise of smoothly blended sound, for example, recalls Muzak’s mission, as quoted in Joseph Lanza’s, Elevator Music: A Surreal History of Muzak, Easy-Listening and Other Moodsong, to eliminate, “factors that distract attention – change of tempo, loud brasses, [and] vocals.”(48) Spotify’s stated desire, “to be the soundtrack of our life, […] to deliver music based on who we are, what we’re doing, and how we’re feeling moment by moment, day by day,” assigns a utilitarian function to its archive of recorded sound, recasting it, like Muzak, as quoted by Lanza again, as, “functional music,”(43) or, “stimulus progression program.” (49)

Cassette and the Contemporary Mixtape

Alongside the commercial playlists’ channeling of the mixtape’s aura there has been a reemergence of cassette, and the mixtape itself, as creative media. Cassette has become a prominent format for a host of underground labels attracted by its low manufacturing and distribution costs as well as its aesthetic qualities. Labels such as The Tapeworm, Opal Tapes, Fort Evil Fruit, and Nyege Nyege Tapes release short-run cassettes (typically 100-150 copies) encompassing noise, field recording, improv, drone, ambience, modular electronics, psychedelia and there ‘out there’ sounds. As Paul Condon of Fort Evil Fruit explains, “producing vinyl is prohibitively expensive and CDs often feel like landfill nowadays. The cassette format is a low-cost means of presenting albums as beautiful physical artifacts when they might otherwise only exist as downloads.”

As well as the economy and physicality of cassette, many enthusiasts are attracted by its sonic characteristics. The tendency of cassettes towards distortion, saturation and phasing are for many positive characteristics. Gruff Rhys of the band Super Furry Animals, for example, has observed that “listening to a cassette tape is not an exact science. Some cassette players play them a little faster. Others distort and phrase the music, changing the sound on the cassette forever.”

Since 2013 the experimental electronic duo Demdike Stare have released a series of cassette only limited edition mixtapes which form a body of work both linked to and distinct from their “official” album and EP releases. Whittaker of the duo has said of their aesthetic that, “Demdike Stare is all about records and the archive of aural culture from the last 50 years.” Where the Spotify playlist seeks to reconfigure the musical archive as functional or background music, artists such as Demdike Stare may be said to explore the recombinant potential of the archive as a vast body of aural culture which can be utilised to create hybrid works spanning temporal and cultural barriers. This reconfiguration of the aural archive arguably attains its most direct distillation on the duo’s mixtapes. These releases combine and overlay original and sampled sound in such a manner that the distinction between one and the other is obscured. They create a hybrid sound world in which sounds from multiple genres, cultures and timeframes overlap and interact, demonstrating what Joseph Standard in Wire magazine has described as, Demdike’s ability to employ sampling “as a means to release the hidden potential they detected in obscure and forgotten records.”

Dissecting 2013’s The Weight of Culture, unsubscribedblog detects:

a wave of static which quickly recedes to usher in a fine piece of Ethio-jazz from Mulatu Astatke…..a burst of the brief Les Soucoupes Volantes Vertes by French electronic prog band Heldon….a minimal rhythm track…overlaid with radio interference, muted voices, cymbals and all manner of audio artefacts before being subsumed by a wavering drone, vinyl static, plucked strings and finger bells.

While The Weight of Culture may be likened to a DJ mix (though one which exists distinct from the rhythm based, dance floor focused requirements which often determine the content of that form) elsewhere Demdike’s mixtapes serve as companion pieces to, or re-imaginings of their more mainstream releases (though again distinct from the more common forms of the remix or dub album). Circulation (2017) is “an hour-long mixtape/sketchbook of ideas and influences for…[their] Wonderland album, contrasting its heavily rhythmic stylings with this largely ambient-affair comprising archival tracks, bespoke edits and re-contextualised classics.” The Feedback Loop (2018) meanwhile reassembles elements of the catalogue of Italian improv collective Il Gruppo Di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza into a new collage composition and performance. As the duo themselves explain:

Tasked by the Festival Nuova Consonanza for a live performance at their 53rd Edition, with the remaining gruppo members in attendance, (Ennio Morricone, Giancarlo Schiaffini, Giovanni Piazza, Alessandro Sbordoni) we apprehensively dived into our collections for pieces by Gruppo and it’s members in order to create this homage. Using samplers, synths and effects we looped and layered chosen sections to create new pieces which we had to then play in front of the mighty Il Gruppo, captured here for posterity.

Demdike Stare, Postcollapse cassette and packaging

The German electronic composer Hainbach also reimagines the mixtape as a recombinant performance/composition hybrid. His YouTube series of C45 Lo-Fi Ambient mixtapes utilises his own self-made cassette loops, manipulated using modified cassette recorders and custom technology, and mixed amongst those of artists drawn from the contemporary underground cassette scene. The artist describes the first of these, C45 #1 | Lo-Fi Ambient Mixtape, as, “a grungy, half-speed lo-fi mix I made in one take with two cassette recorders, the Koma Electronics Fieldkit and a delay.”

What Hainbach calls mixtapes are audio visual records of live studio performances with the artist documenting the creation of the piece via video. They contain a participatory element and viewers/listeners are invited to send their own tapes to be, “mangled,” while the techniques and equipment employed are detailed in videos such as Tape Ambient Music Techniques | Making Of C45, and modification specs for some of the equipment used, such as Gijs Gieskes’ modified walkman are also available online.

Defining the Mixtape

Analysis of these works, along with more historical forms of the mixtape, suggests a set of characteristics which may be said to warrant the use of the term mixtape, even in a context wherein there is no engagement with the original material form of the medium, the cassette tape, which gave rise to the term.

- Hybridity: The mixtape is a uniquely hybrid form, part composition, part compilation. It combines elements from multiple sources, media and timeframes and frequently blurs lines between read and write cultures, or cultural consumption and production.

- Distribution: Mixtapes are distributed via non-mainstream methods. This may be via personal exchange, mail order, download from non corporate/commercial websites, purchase from merch stands at gigs, or via non-mainstream formats (in which category the cassette tape may now be placed).

- Intervention: The creator of a mixtape must be able to intervene in the recording process and to attain control over what is heard, to affect where sounds begin and end, to overlay material, and to combine elements from multiple sources.

- Labour: The creation of a mixtape involves an investment of labour at least equal to that required to listen to it in full. This time, effort, and investment of labour differentiates the mixtape from the playlist, mix CD, or disc drive filled with MP3s, often created simply by dragging and dropping file references from one window to another or via algorithmic selection.

Why set parameters around the mixtape as a genre? These characteristics may also form a series of strategies to counteract contemporary crises in how we create, distribute, listen to, and consume music – some of which are identified in the consideration of Spotify playlists within this article. The creation of hybrid works which are not easily defined or categorised, for example, might push back against the drive to assign a utilitarian function to music – to reframe it as something that happens in the background while we chill or do our chores. It might also serve as a form of resistance to the homogenisation of music and of DJ culture while also giving rise to new forms and practices.

Consideration of how and by whom music is distributed could help sustain a culture that supports independent artists and labels as opposed to corporations, brands and their marketing teams. Maintaining the ability to intervene in and act upon recorded sound sustains the ability to ‘play’ with sound and retains the potential for new forms in the lineage of the mixtape, or genres such as turntablism to emerge. Awareness of how the labour of musicians and music lovers is utilised and of who benefits from it may also serve to diminish the capacity for the exploitation of this labour.

—

Featured Image: “Untitled” by Flickr user Jenna Post (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Mike Glennon is a Dublin based composer, audio visual artist and academic. His compositions and audiovisual works have featured in digital arts exhibitions and at music and film festivals in locations including the Venice, Paris, New Orleans and Dublin. He has been commissioned as a composer by organisations including the National Museum of Ireland and Dublin City Council. As a member of the band the 202s his music has been released to positive critical notice across Europe by Harmonia Mundi / Le Son du Maquis making him labelmates with artists including Cluster, Faust and A Certain Ratio. Mike is currently a PhD Research Scholar in the Graduate School of Creative Arts & Media (GradCAM) at the Dublin Institute of Technology where his research focuses upon the aesthetics of post-digital electronic music. He recently premiered new work stemming from his research at the Research Pavilion of the Venice Biennale thanks to the support of Culture Ireland.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Pushing Play: What Makes the Portable Cassette Recorder Interesting?–Gus Stadler

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music–-Primus Luta

Tape Hiss, Compression, and the Stubborn Materiality of Sonic Diaspora–Christopher Chien

Recent Comments