The Cyborg’s Prosody, or Speech AI and the Displacement of Feeling

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It kicked off with Amina Abbas-Nazari’s post, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice. Then, Golden Owens took a deep historical dive into the racialized sound of servitude in America and how this impacts Intelligent Virtual Assistants. Last week, Michelle Pfeifer explored how some nations are attempting to draw sonic borders, despite the fact that voices are not passports. Today, Dorothy R. Santos wraps up the series with a meditation on what we lose due to the intensified surveilling, tracking, and modulation of our voices. [To read the full series, click here] –JS

—

In 2010, science fiction writer Charles Yu wrote a story titled “Standard Loneliness Package,” where emotions are outsourced to another human being. While Yu’s story is a literal depiction, albeit fictitious, of what might be entailed and the considerations that need to be made of emotional labor, it was published a year prior to Apple introducing Siri as its official voice assistant for the iPhone. Humans are not meant to be viewed as a type of technology, yet capitalist and neoliberal logics continue to turn to technology as a solution to erase or filter what is least desirable even if that means the literal modification of voice, accent, and language. What do these actions do to the body at risk of severe fragmentation and compartmentalization?

I weep.

I wail.

I gnash my teeth.

Underneath it all, I am smiling. I am giggling.

I am at a funeral. My client’s heart aches, and inside of it is my heart, not aching, the opposite of aching—doing that, whatever it is.

Charles Yu, “Standard Loneliness Package,” Lightspeed: Science Fiction & Fantasy, November 2010

Yu sets the scene by providing specific examples of feelings of pain and loss that might be handed off to an agent who absorbs the feelings. He shows us, in one way, what a world might look and feel like if we were to go to the extreme of eradicating and off loading our most vulnerable moments to an agent or technician meant to take on this labor. Although written well over a decade ago, its prescient take on the future of feelings wasn’t too far off from where we find ourselves in 2023. How does the voice play into these connections between Yu’s story and what we’re facing in the technological age of voice recognition, speech synthesis, and assistive technologies? How might we re-imagine having the choice to displace our burdens onto another being or entity? Taking a cue from Yu’s story, technologies are being created that pull at the heartstrings of our memories and nostalgia. Yet what happens when we are thrust into a perpetual state of grieving and loss?

Humans are made to forget. Unlike a computer, we are fed information required for our survival. When it comes to language and expression, it is often a stochastic process of figuring out for whom we speak and who is on the receiving end of our communication and speech. Artist and scholar Fabiola Hanna believes polyvocality necessitates an active and engaged listener, which then produces our memories. Machines have become the listeners to our sonic landscapes as well as capturers, surveyors, and documents of our utterances.

The past few years may have been a remarkable advancement in voice tech with companies such as Amazon and Sanas AI, a voice recognition platform that allows a user to apply a vocal filter onto any human voice, with a discernible accent, that transforms the speech into Standard American English. Yet their hopes for accent elimination and voice mimicry foreshadow a future of design without justice and software development sans cultural and societal considerations, something I work through in my artwork in progress, The Cyborg’s Prosody (2022-present).

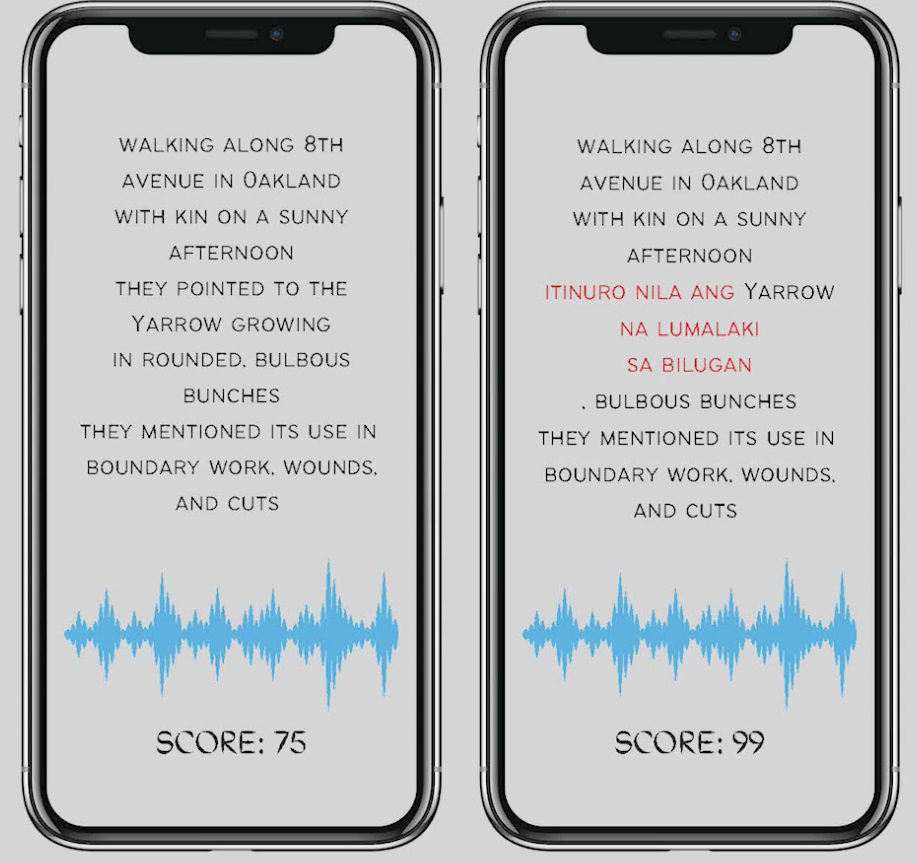

The Cyborg’s Prosody is an interactive web-based artwork (optimized for mobile) that requires participants to read five vignettes that increasingly incorporate Tagalog words and phrases that must be repeated by the player. The work serves as a type of parody, as an “accent induction school” — providing a decolonial method of exploring how language and accents are learned and preserved. The work is a response to the creation of accent reduction schools and coaches in the Philippines. Originally, the work was meant to be a satire and parody of these types of services, but shifted into a docu-poetic work of my mother’s immigration story and learning and becoming fluent in American English.

Even though English is a compulsory language in the Philippines, it is a language learned within the parameters of an educational institution and not common speech outside of schools and businesses. From the call center agents hired at Vox Elite, a BPO company based in the Philippines, to a Filipino immigrant navigating her way through a new environment, the embodiment of language became apparent throughout the stages of research and the creative interventions of the past few years.

In Fall 2022, I gave an artist talk about The Cyborg’s Prosody to a room of predominantly older, white, cisgender male engineers and computer scientists. Apparently, my work caused a stir in one of the conversations between a small group of attendees. A couple of the engineers chose to not address me directly, but I overheard a debate between guests with one of the engineers asking, “What is her project supposed to teach me about prosody? What does mimicking her mom teach me?” He became offended by the prospect of a work that de-centered his language, accent, and what was most familiar to him.The Cyborg’s Prosody is a reversal of what is perceived as a foreign accented voice in the United States into a performance for both the cyborg and the player. I introduce the term western vocal drag to convey the caricature of gender through drag performance, which is apropos and akin to the vocal affect many non-western speakers effectuate in their speech.

The concept of western vocal drag became a way for me to understand and contemplate the ways that language becomes performative through its embodiment. Whether it is learning American vernacular to the complex tenses that give meaning to speech acts, there is always a failure or queering of language when a particular affect and accent is emphasized in one’s speech. The delivery of speech acts is contingent upon setting, cultural context, and whether or not there is a type of transaction occurring between the speaker and listener. In terms of enhancement of speech and accent to conform to a dominant language in the workplace and in relation to global linguistic capitalism, scholar Vijay A. Ramjattan states in that there is no such thing as accent elimination or even reduction. Rather, an accent is modified. The stakes are high when taking into consideration the marketing and branding of software such as Sanas AI that proposes an erasure of non-dominant foreign accented voices.

The biggest fear related to the use of artificial intelligence within voice recognition and speech technologies is the return to a Standard American English (and accent) preferred by a general public that ceases to address, acknowledge, and care about linguistic diversity and inclusion. The technology itself has been marketed as a way for corporations and the BPO companies they hire to mind the mental health of the call center agents subjected to racism and xenophobia just by the mere sound of their voice and accent. The challenge, moving forward, is reversing the need to serve the western world.

A transorality or vocality presents itself when thinking about scholar April Baker-Bell’s work Black Linguistic Consciousness. When Black youth are taught and required to speak with what is considered Standard American English, this presents a type of disciplining that perpetuates raciolinguistic ideologies of what is acceptable speech. Baker-Bell focuses on an antiracist linguistic pedagogy where Black youth are encouraged to express themselves as a shift towards understanding linguistic bias. Deeply inspired by her scholarship, I started to wonder about the process for working on how to begin framing language learning in terms of a multi-consciousness that includes cultural context and affect as a way to bridge gaps in understanding.

Or, let’s re-think this concept or idea that a bad version of English exists. As Cathy Park Hong brilliantly states, “Bad English is my heritage…To other English is to make audible the imperial power sewn into the language, to slit English open so its dark histories slide out.” It is necessary for us all to reconfigure our perceptions of how we listen and communicate that perpetuates seeking familiarity and agreement, but encourages respecting and honoring our differences.

—

Featured Image: Still from artist’s mock-up of The Cyborg’s Prosody(2022-present), copyright Dorothy R. Santos

—

Dorothy R. Santos, Ph.D. (she/they) is a Filipino American storyteller, poet, artist, and scholar whose academic and research interests include feminist media histories, critical medical anthropology, computational media, technology, race, and ethics. She has her Ph.D. in Film and Digital Media with a designated emphasis in Computational Media from the University of California, Santa Cruz and was a Eugene V. Cota-Robles fellow. She received her Master’s degree in Visual and Critical Studies at the California College of the Arts and holds Bachelor’s degrees in Philosophy and Psychology from the University of San Francisco. Her work has been exhibited at Ars Electronica, Rewire Festival, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and the GLBT Historical Society.

Her writing appears in art21, Art in America, Ars Technica, Hyperallergic, Rhizome, Slate, and Vice Motherboard. Her essay “Materiality to Machines: Manufacturing the Organic and Hypotheses for Future Imaginings,” was published in The Routledge Companion to Biology in Art and Architecture. She is a co-founder of REFRESH, a politically-engaged art and curatorial collective and serves as a member of the Board of Directors for the Processing Foundation. In 2022, she received the Mozilla Creative Media Award for her interactive, docu-poetics work The Cyborg’s Prosody (2022). She serves as an advisory board member for POWRPLNT, slash arts, and House of Alegria.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Your Voice is (Not) Your Passport—Michelle Pfeifer

“Hey Google, Talk Like Issa”: Black Voiced Digital Assistants and the Reshaping of Racial Labor–Golden Owens

Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication –Amina Abbas-Nazari

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–Steph Ceraso

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

Look Who’s Talking, Y’all: Dr. Phil, Vocal Accent and the Politics of Sounding White–Christie Zwahlen

Listening to Modern Family’s Accent–Inés Casillas and Sebastian Ferrada

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Recent Comments