The Magical Post-Horn: A Trip to the BBC Archive Centre in Perivale

Suddenly we heard a Tereng! tereng! teng! teng! We looked round, and now found the reason why the postilion had not been able to sound his horn: his tunes were frozen up in the horn, and came out now by thawing, plain enough, and much to the credit of the driver. —The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, 1865

At the BBC Archive Centre in Perivale, London, the proverbial “weight of the past” becomes literal for researchers of sound history. Housed in a massive, unattractive hangar-like building in an industrial park to the northwest of London, the archives suit their environment, one which speaks of practical and solid shapes far more than the lyrical, dainty ivory tower. And by weight, I mean by serious, and sometimes dangerous, poundage: the very first machine created to record off of radio, invented around 1930, was a steel pedestal with bus wheel-sized reels on either side. Audio Coordinator of the BBC Archives, John Dell, explained that not only was this machine laborious to load, but it used magnetic steel tape as its recording surface, which could come free from the reels and lacerate incautious operators as it unspooled and bunched.

The weight of these objects, however, is also metaphoric. The earliest recording in my personal audio drama library, sourced off the invaluable Archive.org, is a 1933 episode of Front Page Drama, a dramatized version of an American Weekly Hearst publication. The past stands monumentally huge if this type of machine, the Marconi-Stille Wire Recorder, was the apparatus that allowed those 15 minutes of 1933 to be captured and, eventually, fed into my 2015 headphones as an MP3.

I listen to much of my audio drama, whether old and crackling like Front Page Drama, or new and podcast-y, while commuting, usually on the London Underground. The episode of Front Page Drama in question I heard during a marathon session when I knew very little could or would interrupt me: on an twelve-hour transatlantic plane ride. I quite like the audio-visual play between listening to audio drama that is new to me versus the familiar but never identical sights of the commute; as Primus Luta remarked in 2012, it’s rare for us to engage our full attention on the aural medium.

While listening to Front Page Drama and episodes of Lum and Abner on that flight, I had to wonder how I was prioritizing my listening time. Who had recorded these episodes from the 1930s? Who had later taken the trouble to digitize them and upload them to Archive.org? Why, for example, were these particular recordings freely available yet I couldn’t find an MP3 anywhere of texts I wanted to share more widely, such as Don Haworth’s On a Summer’s Day in a Garden (1975) or Angela Carter’s Come Unto These Yellow Sands (1978)? Both of these recordings are in the BBC back catalogue; I know, because the BBC supplied them to me—but only the basis of a visit to the archive.

Archive.org is bountiful and accessible, the Perivale archives much more exclusive, but both seem to lack curation. The only hope for accessing things like Haworth or Carter outside the British Library’s Sound and Moving Image Archives is that someday a rogue MP3 or BitTorrent will show up online. The archive does seem, in Neil Verma’s words, then, “transformed before dispersing in space, plucked from the air and mineralized like fossils” (Theater of the Mind, 227); like Primus Luta’s weighty but playful experiment, Schrödinger’s Cassette, which suspended music in concrete to be risked, or remain aurally untouched forever. This seems too often to be the impossible choice.

BBC Perivale Field Trip, Image by Flickr User Hatters! (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The BBC archive storage is eclectic and generally arranged for access by BBC staff rather than for researchers. The BBC Written Archives at Caversham are restricted to academics, and likewise, the speed of gaining access to sound files from Perivale is predicated on the amount of time BBC staff have to devote to it—naturally, the BBC’s own departments have priority, such as BBC Radio 4 Extra, the archival digital radio station, whose backlog of requests for digitised material from the Perivale archive apparently covers 20 pages. The sound collections consist of commercial recordings on shellac (90 RPM records) and vinyl (78 RPMs) as well as impressively dinner-plate sized compilation transcriptions which require a special turn-table on which to play and digitize them. The BBC Sheet Music archive is in Perivale, as well, with original handwritten scores filling shelves.

The second half of the British and Irish Sound Archives conference 2015 afforded a privileged glimpse of the archive storage and technical facilities housed on site. Most of my fellow attendees were archivists of one sort or another, asking detailed questions about transcription devices, fidelity, and storage. Having recently completed my PhD from Swansea University in English in radio drama, I had made countless requests to this very facility through the British Library’s Sound and Moving Image request service; now I, at long last, hoped to see where my digitised sound files were coming from. However, we weren’t shown any recordings made on tape cassette or CD but instead Betamax audio-only. Unseen, too, were the data banks holding all the digitised content, but what myself and my fellow archivists had mainly come to see were the tangible objects making this content possible.

78s at BBC Perivale, Image by Flicker User Hatters! CC BY-NC 2.0

In the physical copies of the Radio Times of the 1940s and ‘50s, also housed at the British Library at St Pancras (and now available, like all of the Radio Times up to 2009, on BBC Genome), there can be found a little asterisk in the listings for drama, which signifies that the drama was broadcast from a recording, rather than live. The later recording machines of the ‘30s through ‘50s, upon which these recordings would have been made, did not decrease appreciably in size, though perhaps in weight. “If I were to drop this,” Dell told us as he carefully handled a dark blue celluloid tube, about the size and circumference of a toilet paper roll, “it would bounce. I’m not going to drop it,” he added. Then the magic began: via a custom-made device, we heard a few bars of a music hall song from circa 1900. The recording was surprisingly clear. It was agonizing when Dell turned it off after only a few seconds.

There is something incredibly seductive about old recordings. In “The Recording that Never Wanted to Be Heard and Other Stories of Sonification,” from The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies, Jonathan Sterne and Mitchell Akiyama question the desire for “sonification” of ever-older recordings, especially when such desires manifest in the creation of a digital sound file in 2008 for “the world’s oldest recording,” a phonoautogram from 1860, which was nevertheless never intended to be played back—the phonoautograph was intended as a device to make the aural visual (555). Radio drama writer Mike Walker really summed up the seduction of old recordings for me in his 2013 BBC Radio 4 ghost story The Edison Cylinders, with a character who is seduced as a scholar and as a participant in a time-traveling mystery by old recordings: a sound engineer in need of money, she agrees to digitize what seem like boring diary entries from a British imperialist, only to be intrigued by his Victorian domain beyond her rather empty modern existence. Unfortunately for her, these particular recordings are reaching beyond the grave to try to kill her.

Edison Cylinder Exposed, by Flickr User fouro boros, CC BY-NC 2.0

Although they do reach out from the grave, most early sound recordings aren’t out to kill you. They do however, present common and vexing issues of authenticity. By this, I mean specifically the provenance of the recording—is the recording of who or what it says it is? On the first day of the conference, Dell regaled us with tales of two cylinder recordings surfacing in the mid-twentieth century, of William Gladstone giving a speech. The words of the speech were identical, but the voices were completely different. Who was the real Gladstone? How could you authenticate the voice of a dead person? Dell further deepened the mystery by telling us the tale of two boxes of wax cylinder recordings in the Perivale archive, whose provenance is torturously (and tantalizingly) unclear. We glimpsed these mysterious, yellow-cream-colored cylinders, somewhat wider and fatter than the celluloid tubes, in situ, but were they original Edison cylinders from the 1880s? The piercing desire to believe these cylinders might contain the voices of Gladstone, the future Edward VIII, or even Henry Irving, are potentially “perils of over-optimism,” as Dell puts it.

All the archivists at this event referred to the serendipity of discovering surprises on recordings. Simon Elmes, whose official title reads “Radio Documentarist, Creative Consultant, and Former Creative Director, BBC Radio Documentaries,” made this manifest as he discussed a subject treated in his documentary from 2005, Ambridge in the Decade of Love. The Archers—an exceptionally long-running BBC radio soap which conjures up visions of rural Englishness and persists among a very dedicated, though mostly older, fan base—like much radio drama and emblematic of gendered attitude toward radio soaps, was not recorded in its first few decades.

Empty Shelves at BBC Perivale, Image by Flickr User Bill Thompson, Image cropped by SO!, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Likewise, anyone researching radio drama before the 1930s is playing a game of roulette; whether any scripts survive will depend entirely on the literary reputation of the author who may have had enough clout to publish them in book form. Even in the case of Lance Sieveking, the acknowledged creative aesthete behind early BBC radio drama, we lack concrete evidence of his most important work, The End of Savoy Hill (1932). And The Truth About Father Christmas (1923), the first original drama written specifically for British radio? Forget about it—it was made for children’s radio.

To return to The Archers, though daily 15-minute scripts were being churned out by Ted Kavanagh from the first years of the 1950s, the broadcasts themselves went missing into the ether (after all, no one suspected the show would still be going after sixty years). Transcription discs, meant for an overseas market, were found in a box in the BBC Archives, giving a reasonably complete overview of The Archers during the 1950s and ‘60s. Elmes was ebullient about this discovery.

While I got the general sense that the other archivists at the conference were amused but indifferent toward this particular trove, to me it was inspiring. I believe the future of audio drama will rely more and more on serials, so the rediscovery of these Archers episodes epitomizes to me the past, present, and future of audio drama in that it speaks of audience involvement and even audience interaction or co-production, which seems key for audio drama going forward, and the aspect of serialization which has vastly overtaken the single drama on television if not on radio.

Harry Oakes as Dan Archer and Gwen Berryman as Doris Archer, 1955.

Nevertheless, even if pursuit of these aural rainbows is a foolish one, such desire also enables scholarship. The hope of finding “originals” inspired me personally to discover the birth of what can conceivably called audio drama. Having researched audio drama from the first known broadcast dramas in English (the adaptations: 2LO London’s Five Birds in a Cage in 1922, WGY Schenectady’s The Wolf in 1922, British Broadcasting Company’s Twelfth Night in 1923; original drama: WLW Cincinnati’s When Love Awakens in 1923, British Broadcasting Company’s Danger in 1924), I was astounded to learn that listeners from World War I might have enjoyed short, dramatized stories on the celluloid tubes (according to Tim Crook, the first audio drama of this nature is a war drama from 1917). While archives such as the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project of the University of California at Santa Barbara care for these recordings in the same way they do for musical and speech recordings, there is a significant lack of scholarship on them.

If commentary on specific pre-radio audio drama is scarce, it is heartening to read dissections of the performative aspects of “actuality,” such as Brian Hanrahan’s anatomy of Gas Shell Bombardment, 1918. Wonderfully, in discussing the “staging” of this war-time recording, Hanrahan brings in traditions from theatre and silent film in addition to the phonograph. Professor David Hendy has persuasively argued that some of the organizing tenets behind the British Broadcasting Corporation, whose management was by and large made up of ex-soldiers, was predicated on a desire for silence and calm, ordered, managed sound after the cacophony of war. Perhaps “cylinder” drama, then, is not really of its time and properly belongs to earlier, or later, cultural milieux.

Wax cylinder playback at BBC Perivale, Image by Flickr User Hatter! CC BY-NC 2.0

The ephemera of the medium presents a recurring problem in radio drama studies, a weighty feeling of doom. With the future of the BBC’s existence currently perilous, one wonders what the consequences will be for archives like those housed at Perivale. If the internal function of the archives (for the BBC to make use during Radio 4 Extra broadcasts, for example) disappears, will the archives be opened to wider use? Or will material without commercial potential simply be discarded? Who would make the decision as to what was commercially viable and how would they make such decisions?

And the problem with the medium seemingly begins with wax cylinders. A beautiful, lyrical story from Baron Munchausen—alias Rudolph Erich Raspe, a German author who created a fictional travel writer and chronic teller of tall tales based on a real nobleman infamous for his boasting—cited by many of those fascinated with sound recordings is worth repeating here: the Baron is traveling in Russia in a snowy landscape and desires the postilion to blow his horn to alert other travellers that their sleigh will be coming around the bend. Unfortunately, the cold makes the horn incapable of any audible sound. Disappointed, they make their way to an inn. Diedre Loughridge and Thomas Patteson cite the “Frozen Horn” from their online Museum of Imaginary Instruments: “After we arrived at the end inn, my postilion and I refreshed ourselves: he hung his horn on a peg near the kitchen fire; I sat on the other side.” Warmed by the fire, the horn now begins to play its reserved tunes.

Illustration by Gustave Doré, 1865. Listen to ABC radio feature on the “Frozen Post Horn” and the Museum of Imaginary Instruments here

With a little leap of the imagination, it’s not difficult to see the parallels with the reality of sound recording limitation. The wax cylinders could only be played a few times before the sound degrades completely. Tin cylinders are not much better. This is the reason why the two Gladstone voices could be both “real” and “fake.” Celluloid is more durable, yet witness the reluctance of Dell to play one for longer than a few seconds, for preservation reasons.

Sound recordings are only as good as the medium on which they are recorded, a fact that surprisingly holds true even today. We were told by our BBC hosts that discs of shellac, vinyl, and acetate whose contents have already been digitised will not be discarded—digital recordings are ultimately taken from these physical originals.

In the future, we might invent means of reproduction and playback which could provide more fidelity to the original event lifted from the physical recording, in which case it will be the MP3s that will be redundant. There’s something both very modern and very old-fashioned about this. Once at a dinner party, I launched full-force into my postdoctoral rant about the eventual possible degradation of the MP3 as a recording format, that it was not infallible as we had been led to believe. I was surprised that I was wholly believed; furthermore, the older people participating in the conversation rued the disappearance of their CDs, tape cassettes and, vitally, their LPs, for the oft-cited reasons (which Primus Luta distills as the pricelessness of old recordings to one’s personal history, and the “fuller” sound ans weighty materiality, one resonating with one’s emotional past).

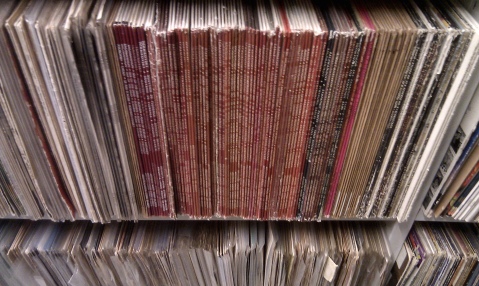

Vinyl at BBC Perivale, including a lot of John Peel’s old records. Image by Flickr User Hatter! (CC BY-NC 2.0)

I admit, before I came to the UK and experienced the never-perfect but always interesting presence of BBC Radio, I treated radio as a background medium. I suppose recorded sound had always interested me, and I had had a strong relationship with local, classical music radio (Classical KHFM Albuquerque). However, I could not have predicted ten years ago that I would become a passionate proponent of audio drama and sound studies more generally. I’m almost embarrassed now at my excessive love of audio drama; I make almost no distinctions between “high” art like Samuel Beckett and Tom Stoppard and fan fiction radio serials like Snape’s Diaries as produced by Misfits Audio: I listen to almost anything.

And, truly, the future of audio drama is only assured if people keep listening. The digitisation and availability of cylinder recordings makes study of them more accessible, so the way is paved for further studies of the earliest audio drama. It is imperative that researchers continue to request sound recordings from the BBC, even if they have to use the relatively inconvenient system currently available.

There are signs that things are improving and that more people than ever before want to access such materials. As Josh Shepperd puts it brilliantly, “Sound trails continue where paper trails end.” As Director of the Radio Preservation Task Force at the Library of Congress, his efforts have underlined the fact that often it is the local and the rural whose radio or audio history vanishes more quickly than the national or the metropolitan. This would historically be the case with the BBC as well, which for a long time privileged London sound above regionalism (and, some would argue, still does). Since 2015, the British Library (and the Heritage Lottery Fund) have invested significantly in the Save Our Sounds campaign, positing that within 15 years, worldwide sound recordings must be digitized before recordings degrade or we no longer have the means to play the material.

Out of curiosity, I downloaded the more than 600-page listing, the Directory of UK Sound Collections, assembled rather hastily through the Save Our Sounds project in 20 weeks, and comprising more than 3,000 collections and more than 1.9 million objects. This document makes for fascinating and eclectic reading, ranging as it does between a Sound Map of the English town of Harrogate to the archives of the Dog Rose Trust, which mainly provides recorded tours of English cathedrals for those who are blind. Undoubtedly, there are wodges of local or forgotten drama in these archives, too. The linking up of these archives and making them more widely accessible suggests how important sustained, collective effort is to unfreezing radio’s archival post-horn, delivering more of its unique tunes.

—

Featured Image: “The Route to Open Data” at BBC Perivale, Image by Flickr User Hatter! (CC BY-NC 2.0)

—

Leslie McMurtry has a PhD in English (radio drama) and an MA in Creative and Media Writing from Swansea University. Her work on audio drama has been published in The Journal of Popular Culture, The Journal of American Studies in Turkey, and Rádio-Leituras. Her radio drama The Mesmerist was produced by Camino Real Productions in 2010, and she writes about audio drama at It’s Great to Be a Radio Maniac.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Only the Sound Itself?: Early Radio, Education, and Archives of “No-Sound”–Amanda Keeler

“Share your story” – but who will listen?–Fabiola Hanna

SO! Amplifies: Indie Preserves

The Sound of Radiolab: Exploring the “Corwinesque” in 21st Century–Alexander Russo

Share this:

On Whiteness and Sound Studies

This is the first post in Sounding Out!’s 4th annual July forum on listening in observation of World Listening Day on July 18th, 2015. World Listening Day is a time to think about the impacts we have on our auditory environments and, in turn, their effects on us. For Sounding Out! World Listening Day necessitates discussions of the politics of listening and listening as a political act, beginning this year with Gustavus Stadler’s timely provocation. –Editor-in-Chief JS

This is the first post in Sounding Out!’s 4th annual July forum on listening in observation of World Listening Day on July 18th, 2015. World Listening Day is a time to think about the impacts we have on our auditory environments and, in turn, their effects on us. For Sounding Out! World Listening Day necessitates discussions of the politics of listening and listening as a political act, beginning this year with Gustavus Stadler’s timely provocation. –Editor-in-Chief JS

—

Many amusing incidents attend the exhibition of the Edison phonograph and graphophone, especially in the South, where a negro can be frightened to death almost by a ‘talking machine.’ Western Electrician May 11, 1889, (255).

What does an ever-nearer, ever-louder police siren sound like in an urban neighborhood, depending on the listener’s racial identity? Rescue or invasion? Impending succor or potential violence? These dichotomies are perhaps overly neat, divorced as they are from context. Nonetheless, contemplating them offers one charged example of how race shapes listening—and hence, some would say, sound itself—in American cities and all over the world. Indeed, in the past year, what Jennifer Stoever calls the “sonic color line” has become newly audible to many white Americans with the attention the #blacklivesmatter movement has drawn to police violence perpetrated routinely against people of color.

Racialized differences in listening have a history, of course. Consider the early decades of the phonograph, which coincided with the collapse of Reconstruction and the consolidation of Jim Crow laws (with the Supreme Court’s stamp of approval). At first, these historical phenomena might seem wholly discrete. But in fact, white supremacy provided the fuel for many early commercial phonographic recordings, including not only ethnic humor and “coon songs” but a form of “descriptive specialty”—the period name for spoken-word recordings about news events and slices of life—that reenacted the lynchings of black men. These lynching recordings, as I argued in “Never Heard Such a Thing,” an essay published in Social Text five years ago, appear to have been part of the same overall entertainment market as the ones lampooning foreign accents and “negro dialect”; that is, they were all meant to exhibit the wonders of the new sound reproduction to Americans on street corners, at country fairs, and in other public venues.

Thus, experiencing modernity as wondrous, by means of such world-rattling phenomena as the disembodiment of the voice, was an implicitly white experience. In early encounters with the phonograph, black listeners were frequently reminded that the marvels of modernity were not designed for them, and in certain cases were expressly designed to announce this exclusion, as the epigraph to this post makes brutally evident. For those who heard the lynching recordings, this new technology became another site at which they were reminded of the potential price of challenging the racist presumptions that underwrote this modernity. Of course, not all black (or white) listeners heard the same sounds or heard them the same way. But the overarching context coloring these early encounters with the mechanical reproduction of sound was that of deeply entrenched, aggressive, white supremacist racism.

The recent Sonic Shadows symposium at The New School offered me an opportunity to come back to “Never Heard Such a Thing” at a time when the field of sound studies has grown more prominent and coherent—arguably, more of an institutionally recognizable “field” than ever before. In the past three years, at least three major reference/textbook-style publications have appeared containing both “classic” essays and newer writing from the recent flowering of work on sound, all of them formidable and erudite, all of great benefit for those of us who teach classes about sound: The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies (2012), edited by Karen Bijsterveld and Trevor Pinch; The Sound Studies Reader (2013), edited by Jonathan Sterne; and Keywords in Sound (2015), edited by David Novak and Matt Sakakeeny. From a variety of disciplinary perspectives, these collections bring new heft to the analysis of sound and sound culture.

I’m struck, however, by the relative absence of a certain strain of work in these volumes—an approach that is difficult to characterize but that is probably best approximated by the term “American Studies.” Over the past two decades, this field has emerged as an especially vibrant site for the sustained, nuanced exploration of forms of social difference, race in particular. Some of the most exciting sound-focused work that I know of arising from this general direction includes: Stoever’s trailblazing account of sound’s role in racial formation in the U.S.; Fred Moten’s enormously influential remix of radical black aesthetics, largely focused on music but including broader sonic phenomena like the scream of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester; Bryan Wagner’s work on the role of racial violence in the “coon songs” written and recorded by George W. Johnson, widely considered the first black phonographic artist; Dolores Inés Casillas’s explication of Spanish-language radio’s tactical sonic coding at the Mexican border; Derek Vaillant’s work on racial formation and Chicago radio in the 1920s and 30s. I was surprised to see none of these authors included in any of the new reference works; indeed, with the exception of one reference in The Sound Studies Reader to Moten’s work (in an essay not concerned with race), none is cited. The new(ish) American Studies provided the bedrock of two sound-focused special issues of journals: American Quarterly’s “Sound Clash: Listening to American Studies,” edited by Kara Keeling and Josh Kun, and Social Text’s “The Politics of Recorded Sound,” edited by me. Many of the authors of the essays in these special issues hold expertise in the history and politics of difference, and scholarship on those issues drives their work on sound. None of them, other than Mara Mills, is among the contributors to the new reference works. Aside from Mills’s contributions and a couple of bibliographic nods in the introduction, these journal issues play no role in the analytical work collected in the volumes.

The three new collections address the relationship between sound, listening, and specific forms of social difference to varying degrees. All three of the books contain excerpts from Mara Mills’ excellent work on the centrality of deafness to the development of sound technology. The Sound Studies Reader, in particular, contains a small array of pieces that focus on disability, gender and race; in attending to race, specifically, Sterne shrewdly includes an excerpt from Franz Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism, as well as essays on black music by authors likely unfamiliar to many American readers. The Oxford Handbook’s sole piece addressing race is a contribution on racial authenticity in hip-hop. It’s a strong essay in itself. But appearing in this time and space of field-articulation, its strength is undermined by its isolation, and its distance from any deeper analysis of race’s role in sound than what seems to be, across all three volumes, at best, a liberal politics of representation or “inclusion.” Encountering the three books at once, I found it hard not to hear the implicit message that no sound-related topics other than black music have anything to do with race. At the same time, the mere inclusion of work on black music in these books, without any larger theory of race and sound or wider critical framing, risks reproducing the dubious politics of white Euro-Americans’ long historical fascination with black voices.

What I would like to hear more audibly in our field—what I want all of us to work to make more prominent and more possible—is scholarship that explicitly confronts, and broadcasts, the underlying whiteness of the field, and of the generic terms that provide so much currency in it: terms like “the listener,” “the body,” “the ear,” and so on. This work does exist. I believe it should be aggressively encouraged and pursued by the most influential figures in sound studies, regardless of their disciplinary background. Yes, work in these volumes is useful for this project; Novak and Sakakeeny seem to be making this point in their Keywords introduction when they write:

While many keyword entries productively reference sonic identities linked to socially constructed categories of gender, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, citizenship, and personhood, our project does not explicitly foreground those modalities of social difference. Rather, in curating a conceptual lexicon for a particular field, we have kept sound at the center of analysis, arriving at other points from the terminologies of sound, and not the reverse. (8)

I would agree there are important ways of exploring sound and listening that need to be sharpened in ways that extended discussion of race, gender, class, or sexuality will not help with. But this doesn’t mean that work that doesn’t consider such categories is somehow really about sound in a way that the work does take them up isn’t, any more than a white middle-class person who hears a police siren can really hear what it sounds like while a black person’s perception of the sound is inaccurate because burdened (read: biased) by the weight of history and politics.

In a recent Twitter conversation with me, the philosopher Robin James made the canny point that whiteness, masquerading as lack of bias, can operate to guarantee the coherence and legibility of a field in formation. James’s trenchant insight reminds me of cultural theorist Kandice Chuh’s recent work on “aboutness” in “It’s Not About Anything,” from Social Text (Winter 2014) and knowledge formation in the contemporary academy. Focus on what the object of analysis in a field is, on what work in a field is about, Chuh argues, is “often conducted as a way of avoiding engagement with ‘difference,’ and especially with racialized difference.”

I would like us to explore alternatives to the assumption that we have to figure out how to talk about sound before we can talk about how race is indelibly shaping how we think about sound; I want more avenues opened, by the most powerful voices in the field, for work acknowledging that our understanding of sound is always conducted, and has always been conducted, from within history, as lived through categories like race.

The cultivation of such openings also requires that we acknowledge the overwhelming whiteness of scholars in the field, especially outside of work on music. If you’re concerned by this situation, and have the opportunity to do editorial work, one way to work to change it is by making a broader range of work in the field more inviting to people who make the stakes of racial politics critical to their scholarship and careers. As I’ve noted, there are people out there doing such work; indeed, Sounding Out! has continually cultivated and hosted it, with far more editorial care and advisement than one generally encounters in blogs (at least in my experience), over the course of its five years. But if the field remains fixated on sound as a category that exists in itself, outside of its perception by specifically marked subjects and bodies within history, no such change is likely to occur. Perhaps we will simply resign ourselves to having two (or more) isolated tracks of sound studies, or perhaps some of us will have to reevaluate whether we’re able to teach what we think is important to teach while working under its rubric.

—

Thanks to Robin James, Julie Beth Napolin, Jennifer Stoever, and David Suisman for their ideas and feedback.

—

Gustavus Stadler teaches English and American Studies at Haverford College. He is the author of Troubling Minds: The Cultural Politics of Genius in the U. S.1840-1890 (U of Minn Press, 2006). His 2010 edited special issue of Social Text on “The Politics of Recorded Sound” was named a finalist for a prize in the category of “General History” by the Association of Recorded Sound Collections. He is the recipient of the 10th Annual Woody Guthrie fellowship! This fellowship will support research for his book-in-progress, Woody Guthrie and the Intimate Life of the Left.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Reading the Politics of Recorded Sound — Jennifer Stoever

Hearing the Tenor of the Vendler/Dove Conversation: Race, Listening, and the “Noise” of Texts — Christina Sharpe

Listening to the Border: “‘2487’: Giving Voice in Diaspora” and the Sound Art of Luz María Sánchez — Dolores Inés Casillas

Share this:

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Rhetoric After Sound: Stories of Encountering “The Hum” Phenomenon

- Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions

- Wingsong: Restricting Sound Access to Spotted Owl Recordings

- Listening Together/Apart: Intimacy and Affective World-Building in Pandemic Digital Archival Sound Projects

- The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments