Rhetoric After Sound: Stories of Encountering “The Hum” Phenomenon

..

“So I have heard The Hum… The rest of what I’m about to tell you is beyond reasoning, and understanding.” Here, in a Reddit post, Michael A. Sweeney prefaces their story of their first encounter with “the hum,” an unexplained phenomenon heard by only a small percentage of listeners around the world. The hum is an ominous sonic event that impacts communities from Australia to India, Scotland to the United States. And as Geoff Leventhall writes in “Low Frequency Noise: What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Would Like to Know,” the hum causes “considerable problems” for people across the globe—such as nausea, headaches, fatigue, and muscle pain—as it continues to be an unsolved “acoustic mystery” (94).

..

Sweeney’s story of encountering the hum for the first time is remarkable. It begins in Taft, California, which Sweeney recounts as “a podunk little desert bowl town in the middle of nowhere. You can literally drive from one end to the other in under 10min, under 5 if you was speeding.” On this particular night, while walking down the main road of Taft, they report the scene being charged with electricity, and following this charge, hearing a moving sound, a traveling yet invisible sound. “This invisible thing was creating a noise like I had never heard before and sending a wave of static electricity throughout the air in every direction around it,” Sweeney explains. They try to track it down, but to no avail. After following the hum a few blocks and around a couple of corners, it just simply vanishes. As Kristin Gallerneaux aptly claims in her book High Static, Dead Lines: Sonic Spectres and the Object Hereafter, “the Hum’s oppression seems to come from everywhere and nowhere” (196), and this is especially true in Sweeney’s encounter.

While their account of the hum as electrically-charged is exceptional, Sweeney’s story adequately represents both the anomalistic qualities of the hum and its ability to elude a locatable and identifiable source. They attempt to describe the hum during this encounter as “like an invisible traveling vehicle of some sort,” but that, altogether, they are “not really sure” what it is. And they even admit that this explanation “makes no sense… whatsoever.” This difficulty in describing the phenomenon is reaffirmed not only by the stories told by other listeners but, too, the numerous scientific experiments that have been conducted after the hum’s frequent emergence beginning around the 1970s (Deming “The Hum: An Anomalous Sound Heard Around the World” 583).

In the US, two major studies have been conducted on the hum: The first in Taos, New Mexico, and the second in Kokomo, Indiana (Cowan “The Results of Hum Studies in the United States”; Mullins and Kelly “The Mystery of the Taos Hum”). Collectively, nearly three hundred residents in these communities have reported hearing a mysterious hum that exists without a known source. While it may sound like an idling diesel truck engine (Frosch “Manifestations of a Low-Frequency Sound of Unknown Origin Perceived Worldwide, Also known as ‘The Hum’ or the ‘Taos Hum’” 60), a dentist’s drill (Deming 575), “someone’s high-powered audio bass running amok” (Mullins and Kelly “The Elusive Hum in Taos, New Mexico”), or simply just an “invisible force”—as Sweeney claims—it may be none of the above. Musicologist Jorg Muhlhans asserts that “there is no clear evidence for either an acoustic or electromagnetic origin, nor is there an attribution to some form of tinnitus” (“Low Frequency and Infrasound: A Critical Review of the Myths, Misbeliefs and Their Relevance to Music Perception Research” 272). Thus, according to Muhlhans, these studies reveal that while hum’s sensorial impact is that of sound, the phenomenon itself is likely neither acoustic nor electromagnetic.

Beyond the limits of current scientific logics which attempt to make sense of sonic events and their impacts, the hum exists as an exceptional and unknown anomaly. It transcends the valuative limits of current knowledge in acoustics and ways of understanding how sound moves through, across, and within spaces to address potential listeners. “I’m not saying I saw waves of electricity or anything of the sort,” Sweeney adds to their above description of the hum as a sound “charged with electricity.” “It was more of a feeling than something you saw. I could just feel electricity everywhere, and see little tendrils of it from my fingertips as I ran them across each other… I just KNEW it was coming from whatever was making that sound, this invisible force that was traveling down the road.” In such an account, the hum defies scientific explanation, and this fact is supported by the multiple failed investigations into the phenomenon. As Franz Frosch details in their article “Hum and Otoacoustic Emissions May Arise Out of the Same Mechanisms,” some scientists have built multiple “custom shielded chamber[s]” out of copper and magnetic material to test for a potential acoustic or electromagnetic source of the hum (604). These investigations, time after time, can’t provide an answer—leaving it up to listeners of the hum to form their own.

Sweeney’s story—and the endless other stories of the hum that have been told across the world—depict the lived, affective, and rhetorical experience of anomalistic listening. To hear, to listen with the hum, is to experience the affective dimensions of a “sound” that has no apparent acoustic or electromagnetic source. This is because “sonic knowledge is framed through acoustics and experience” (84), as Mark Peter Wright notes in his book Listening After Nature: Field Recording, Ecology, and Critical Practice. So, to listen with the hum is to occupy a state of affection that is altogether unknown to not only science but the listener themself. Sweeney bluntly continues, writing about their experience of the hum, saying, “I only know exactly what I’ve told you today.” To know this sound, for this sound to exist as truth, this unfolds through stories found in the still-to-be-explained.

I consider “after sound” to characterize this felt condition for rhetorical action that is a result of listening beyond or after acoustic valuations. Instead of this being a moment void of sound, “after sound” defines a state of experience that is complicated by an attempt to control the valuative limits of what is and isn’t sonic. In this way, “after sound” only gestures toward the temporal to develop the different emergence of the sensorial. Because the hum affects in a manner similar to sound but without acoustic or electromagnetic origin, people who hear the hum make sense of this relentless experience through a condition that is after sound. Such a claim is represented in Sweeney’s admission that “[they] just have this weird feeling that this story needs to be told. That there’s more to The Hum than anyone has realized, and that maybe it needs to be further studied and looked into” (added emphasis). This felt, “weird feeling” is initiated after sound, and this is what I am considering as the call for rhetorical action. Such an affective, felt, and lived experience may only exist after the “logical” answers, failed scientific studies, and experiments lacking helpful results become determinative of sonic limits.

Further, “after sound” moves from Marie Thompson’s discussion of “source-oriented” noise (30) that she posits in her book Beyond Unwanted Sound: Noise, Affect, and Aesthetic Moralism. Speaking to the phenomenon of the hum, Thompson explains that an “unidentifiable noise is often amplified in perception, grasping the attention of the listener” (29). “After sound” is an hyper-attuned condition wherein the rhetorical actions of listeners are always attentive to what-may-(not)-be acoustics. It is their presence within utter sonic mystery that fuels the potential for persuasive response. And David Deming, a researcher in Geosciences, articulates in his article “The Hum: An Anomalous Sound Heard Around the World” that “in the absence of an answer provided by science, Hum hearers tend to find an explanation and hang on to it” (579), which illustrates the potential for listeners to respond via story within the conditions foregrounded by anomalistic encounters. “After sound” describes a moment of malleability that opens up in soundtime for different negotiations of sense and affect.

Responding to the conditions of listening with story, like Sweeney does, reflects an intention to share and persuade through an expression of sonic experience. As Katherine McKittrick states in her book Dear Science and Other Stories, “story opens the door to curiosity; the reams of evidence dissipate as we tell the world differently, with creative precision” (7). And V. Jo Hsu, speaking to the rhetorical potential of story, elucidates in their book Constellating Home: Trans and Queer Asian American Rhetorics that “story can slow down, hold still, redefine, and/or reimagine our physical movements to renegotiate their shared meanings” (18). How I’m conceiving of storytelling after sound develops from the insights developed by these authors and other scholars exploring the rhetorical potential of story in cultural rhetorics.

Story, in the domain of sound, enables listeners to reconsider how, when, why, and where the sonic is defined and valued. While it must not be the sole rhetorical technology after sound, Sweeney clearly relies on storytelling to make sense of their encounter with the hum. This story and other stories told about the hum illustrate how listeners practice the negotiation of sound’s meaning by collectively exploring ways of investigating and experimenting with(in) phenomena. Telling stories after sound is to reach across and through a community of listeners to find shared truths that come to be through encounters with hearing. Altogether, rhetoric after sound queries the intersection of perception and intelligibility to jostle forward the meaning of listening. At a moment when the world is at a loss for answers, this is a practice of seizing opportunities for hopeful and imaginative intervention into the valuative limits of the sonic.

“I’ll end it here,” Sweeney begins in their last paragraph, “and I can assure you that everything I have told you is the absolute truth. It happened to me and not a friend of a friend. I was awake, I’m not making any of it up, and all I want are REAL answers.” Sweeney’s call for a resolution was posted 10 months ago, in May 2023. And still today, the hum continues to lack answers, and the unsolved mystery continues to impact listeners. More recently, Popular Mechanics reported in a November 2023 article, titled “A Ghostly Nighttime Hum Is Invading Random Towns. Scientists Don’t Know What It Means,” that the hum has reached Omagh in Northern Ireland and that citizens are “trapped inside [of a mystery].” So far, no matter the amount of media coverage nor number of affected people across the world, encounters are ultimately defined by sounds unknown. After sound—when communities of listeners are left behind by these valuative limits—rhetorical action persists in search of an explanation.

—

Featured Image: Spiral by Flickr User Richard CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED

—

Trent Wintermeier is a second-year PhD student in the Department of Rhetoric and Writing at the University of Texas at Austin. He’s a Graduate Research Assistant for the AVAnnotate project, where he helps make audiovisual material more discoverable and accessible. Next year, he will be an Assistant Director for the Digital Writing & Research Lab. His research interests broadly include sound, digital rhetorics, and community. Currently, he’s interested in how researchers can responsibly engage with communities impacted by sound and the local rhetorical ecologies which materialize under sonic conditions.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Becoming a Bad Listener: Labyrinthitis, Vertigo, and “Passing”–Aaron Trammell

Live Through This: Sonic Affect, Queerness, and the Trembling Body–Airek Beauchamp

Listening to Tinnitus: Roles of Media When Hearing Breaks Down—Mack Hagood

My Time in the Bush of Drones: or, 24 Hours at Basilica Hudson–Robert Cashin Ryan

Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions–Matthew Tompkinson

Re-orienting Sound Studies’ Aural Fixation: Christine Sun Kim’s “Subjective Loudness”–Sarah Mayberry Scott

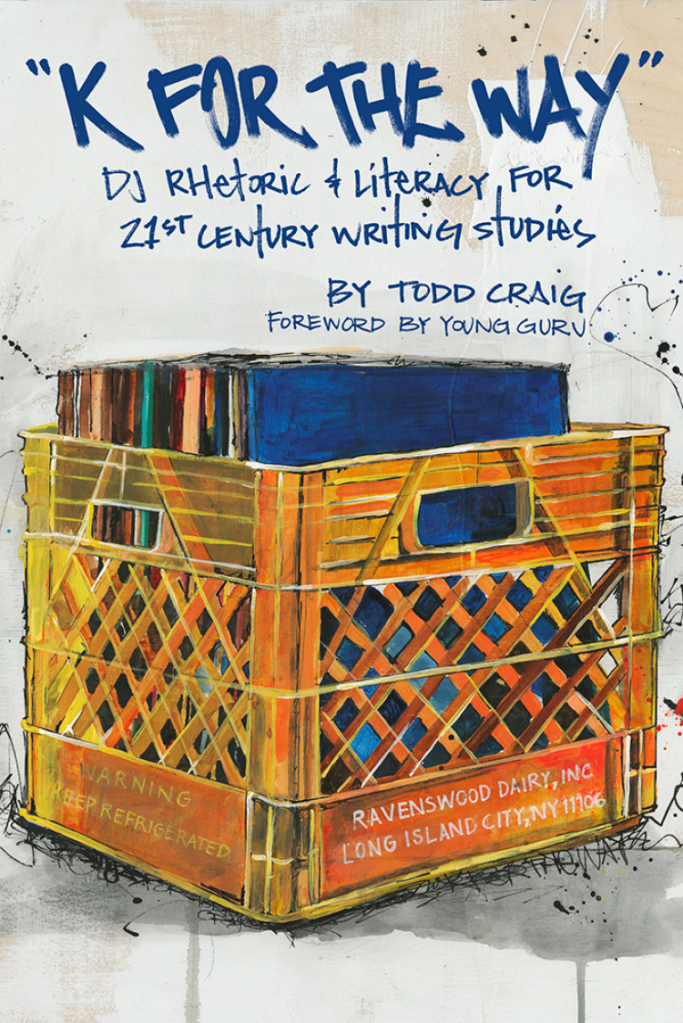

SO! Reads: “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies

or, Last Summer a DJ Saved My Life

“Hip Hop does work that a lot of other things don’t do” Young Guru (viii).

The way that we imagine English Studies, specifically Composition and Rhetoric (Comp/Rhet), today needs a radical shift. Specifically, we need new techniques for Writing Studies pedagogy to reach students in a more meaningful and contemporary fashion. Todd Craig’s “K for the Way:” DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies (Utah State University Press, 2023) both documents the need for this shift and enacts it. Craig’s work enables us to recognize the pedagogical impact on writing that Hip Hop has had over the last 50 years—specifically how the DJ/deejay as twenty-first century new media reader and writer teaches students not just to think about sound, but to compose with it, too.

An Associate Professor of English at CUNY Graduate Center, Craig has little desire to shake the foundations of English Studies, but instead do what Hip Hop has always done—make a way where there is none. The point is to (re)imagine new ways of doing old things; in this case, of teaching and reaching students who arrive in First-Year Writing courses. “K for the Way” does more than demonstrate the ways in which the DJ is a twenty-first century pedagogical savant; it also teaches readers, using DJ Rhetoric and DJ Literacy, about the culture that makes them possible.

This summer, a DJ really did save my life: as someone who feels consistently overwhelmed by the vast nature of scholarly discourse, “K for the Way” gave me a chance to breathe, to identify with something that has been a part of me for the better part of my life, and to see myself in a conversation about a topic I am more than passionate about. For Craig, community, history, and culture are the core of his mission as a scholar, educator, and DJ.

Craig defines several new terms that bridge the worlds of Hip Hop and Composition and Rhetoric. First, we have DJ Rhetoric, which can be understood as the modes, methodologies, and discursive elements of the DJ. For Craig, it “encompasses the quality of oral, written, and sonic language that displays and expresses sociocultural, historical, and musical meanings, attitudes, and sentiments” (23). Next, there is DJ Literacy, which is the “sonic and auditory practices of reading, writing, critically thinking, speaking, and communicating through and with the rhetoric of Hip Hop DJ culture” (23). These two definitions, operating in conjunction, situate the DJ as a kind of griot, a figure that Adam Banks invokes as a carrier of tradition, stories, and histories in Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age (Studies in Writing and Rhetoric) (2011). The mission of the griot is to carry stories and translate them to various audiences while adhering to the rhetorical conventions and modes of whichever audience they find themselves before; similarly, the DJ is responsible for “communicating the pulse and the evolution of a culture that once sat as ‘underground’ but now has dramatically evolved to ‘mainstream’” (25). These definitions serve as guides for the reader as they are tethered to all of the concepts and (re)imagining happening throughout the book.

Craig is intimately close to the work he is doing. He lives and breathes Hip Hop; and what should a book about the Hip Hop DJ be if not written by someone who embodies the role, culture, and practice of DJing? Craig uses a a research methodology known as hiphopography in which Hip Hop ways of being are central to studying it. Coined by James G. Spady, this term is defined as “a shared discourse with equanimity, not the usual hierarchical distancing techniques usually found in published and non-published (visual-TV) interviewers with rappers” (27). Craig states that hiphopography “allowed me to engage a variety of Hip Hop DJs while also maintaining my own shared values and sentiments around my love of Hip Hop culture and DJ practices” (28). Hiphopography constructs a conversational, intimate space—touched by history, culture, and music—wherein the interviewer and interviewee can engage and produce meaningful data. This methodology—and Craig’s many interviews with DJs about their craft—becomes part of the text’s core as we begin to see how Craig’s two-pronged argument connects DJ Rhetoric and DJ Literacy to bring both life throughout the book.

If one understands the DJ as a twenty-first century rhetorician and compositionist and considers the ways in which the DJ is a cultural meaning-maker, sponsor, and master sampler, then one can clearly see the connections between the DJ, DJ culture, and Writing Studies in the contemporary moment. In the first part of his argument supporting the significance of DJ Rhetoric and Literacy in writing pedagogy Craig asserts that, “it is essential that the academy at large works to strengthen students’ undergraduate experiences by reinforcing their racial, ethnic, and cultural ties” (14). This perspective provides the foundation for the second part of his argument that “the DJ (and thus, Hip Hop DJ culture) is the epicenter of Hip Hop culture’s creation” (23). Taken together, these dynamic arguments make the claim that the DJ offers a powerful model of a new media reader, writer, and critic. Today, our students come to writing classrooms with a “vast array of cultural capital. . .in their philosophical and cultural backpacks” (107). If we, as writing teachers, want to honor that cultural capital and build with it, we should follow Craig’s lead and look toward the DJ for some pointers on how to expand students’ access to a language that represents them.

Readers will also see a developing research agenda in “K for the Way” that thinks toward changing the culture beyond the present, while acknowledging the groundwork laid for the current moment and building genealogically upon that foundation, just as DJs do with sampling. Craig best exemplifies this when he writes, “in order to fully engage in a conversation—whether intellectual, pedestrian or otherwise—that discusses what DJ Rhetoric might look like, one has to think about the cultural and textual lineage of sponsors and mentors” (51). This notion of textual lineage is borrowed from Alfred W. Tatum who explains the term as “Similar to lineages in genealogical studies” and continues to note that textual lineage is “made up of texts (both literary and nonliterary) that are instrumental in one’s human development because of the meaning and significance one has garnered from them” (Tatum, qtd. in Craig, 51). Craig builds upon Tatum’s idea by introducing sonic lineage, which follows the same logic as Tatum’s term, but through sound (51). What becomes apparent, is that the DJ, as a cultural sponsor, can deploy sonic lineage as a way of communicating history and culture to members within and outside of the Hip Hop community and, more specifically, DJ culture.

Chapter three, especially, works at the interdisciplinary junction of Sound Studies, Writing Studies, and Hip Hop studies to convey a clear critique of the dominant discourse surrounding plagiarism. Craig is unsatisfied with the black-and-white conception of plagiarism as it presents itself in the academy. As a result, he moves to inquire “how we as practitioners [of teaching composition] approach citation methods and strategies within a twenty-first century landscape” (75). Craig promptly turns us toward the DJ’s conceptualization of sampling as a citation practice. Sampling in Hip Hop, as defined by Andrew Bartlett, “is not collaboration in any familiar sense of the term. It is a high-tech and highly selective archiving, bringing into dialogue by virtue of even the most slight representation” (77). The highly selective archiving, a.k.a crate diggin’, builds upon the idea of sonic lineage.

For the DJ, the process of diggin’ through crates to find that right sound, that one joint that going to get the party jumpin’, is a key element in the practice of “text constructing” (79). The Hip Hop sample functions alongside an understanding, offered by Alasdair Pennycook, of “transgressive-versus-nontransgressive intertextuality,” which, for an academic audience, complicates the idea of plagiarism.. The DJ becomes a figure through which we can understand intertextuality, sampling becomes the practice through which we can see parallels to citation through text construction, and the mix is where we begin, with the help of Pennycook, to complicate notions of plagiarism. In this chapter, readers are able to understand through sound.

Subsequently, Craig explores the concept of revision as it relates to the DJ’s ability to engage with an emcee on the point of “remix as revision” (107). Building from on Nancy Sommers’ article, “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers,” Craig lifts and examines four strategies of revision through the lens of the Hip Hop DJ: deletion, substitution, addition, and reordering (Sommers, qtd. in Craig, 107). These practices not only identify the Hip Hop DJ as a master of revision but also center the DJ, in the context of the writing classroom, as a key figure for understanding editorial practice. As teachers of writing—and especially for those of us who are deeply connected to Hip Hop culture—we have traditional scholars, such as Sommers, but we also have the DJ as cultural scholar, which offer new models with communicating and practicing the craft of writing in the twenty-first century.

Chapter Five, which is co-written by Craig and Carmen Kynard, centers on six women DJs: DJs Spinderella, Pam the Funkstress, Kuttin Kandi, Shorty Wop, Reborn, and Natasha Diggs to work toward developing a “Hip Hop Feminist Deejay Methodology” that positions women in Hip Hop culture as a key source of key knowledge production–as meaning-makers, theoreticians, storytellers–and as tastemakers in twenty-first century discourse about education, technologies, race, and gender. This chapter is also apt representation of hiphopography at work, as both Craig and Kynard ground their position in the interviews of these six women deejays, “deliberately situating their stories first… as opposed to the usual academic expectation that a tedious delineation of methods and an extant literature review come before a discussion of the actual subjects” (123).

In part, this chapter focuses on the affordances and limitations—political, social, and economic—present in DJ culture, and the effects it has on these women DJs to make it do what it does. For example, the introduction of the digital software Serato has simultaneously made access to music easier, and complicated access to the cultural archive that made the music possible in the first place. Natasha Diggs, states, “While she values the ability to access mp3 files so readily, she argues a deejay’s research and craft suffer, because many times the mp3 files do not include information about an artist’s name, history, or band” (129). Pam the Funkstress ties this sentiment up nicely when she argues, “There’s nothing like vinyl” (129).

The final chapter is fashioned like a Hip-Hop outro, with Craig leaving with a few parting ideas. Most important among them is his vision of “Comp 3.0,” a version of Comp/Rhet wherein “we have to push the scope of writing and rhetoric—with or without the field’s permission or acknowledgement” (171). For scholars of composition and rhetoric and writing teachers who ground part of their understanding of the field in Black Studies, Hip Hop, and the DJ, we gotta make it do what it do, regardless of who says what! Comp 3.0 does not seek approval or recognition from the powers that be; instead, it focuses on the new ways of thinking and writing, and of teaching, that we are able to conjure—with history, culture, and practice propelling us—when we invoke that which got us to the academy in the first place.

What is at stake, for those of us who engage Black Studies, Sonic Studies, Comp/Rhet, and Hip Hop Studies as critical points of departure for the teaching of writing, is that our presence—our being, methods, and our teaching—is crucial for developing a genealogy of scholars and world citizens who are aware of the myriad possibilities present in the twenty-first century.

—

Featured Image: Cover Art for “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies by Cathey White

—

DeVaughn (Dev) Harris is a PhD student studying composition and rhetoric in NYC. His academic interests are mainly in writing studies and pedagogy, but those are often supported by other sub-interests in music, creative writing, African American studies, and philosophy. When not reading or writing, Dev enjoys making music wherever and however possible. He has published music before under the collective AbstraktFlowz.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: Classroom Sonic Consciousness in the Playlist Project—Todd Craig

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening--Airek Beauchamp

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom- Carter Mathes

Contra La Pared: Reggaetón and Dissonance in Naarm, Melbourne–Lucreccia Quintanilla

Ill Communication: Hip Hop and Sound Studies–Jennifer Stoever

SO! Amplifies: Regina Bradley’s Outkasted Conversations

A Listening Mind: Sound Learning in a Literature Classroom–Nicole Brittingham Furlonge

Recent Comments