DIANE… The Personal Voice Recorder in Twin Peaks

READERS. 9:00 a.m. April 2nd. Entering the next installment of SO!’s spring series, Live from the SHC, where we bring you the latest from the 2011-2012 Fellows of Cornell’s Society for the Humanities, who are ensconced in the Twin Peaks-esque A.D. White House to study “Sound: Culture, Theory, Practice, Politics.” Enjoy today’s offering from Tom McEnaney, and look for more from the Fellows throughout the spring. For the full series, click here. For cherry pie and coffee, you’re unfortunately on your own. –JSA, Editor in Chief

“I hear things. People call me a director, but I really think of myself as a sound-man.”

—David Lynch

From March 6-April 14 of this year, David Lynch is presenting a series of recent paintings, photographs, sculpture, and film at the Tilton Gallery in New York City. The event marks an epochal moment: the last time Lynch exhibited work in the city was in 1989, just before the first season of his collaboration with Mark Frost on the ABC television series Twin Peaks. At least one painting from the exhibit, Bob’s Second Dream, harkens back to that program’s infamous evil spirit, BOB, and continues Lynch’s ongoing re-imagination of the Twin Peaks world, a project whose most well known product has been the still controversial and polarizing prequel film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.

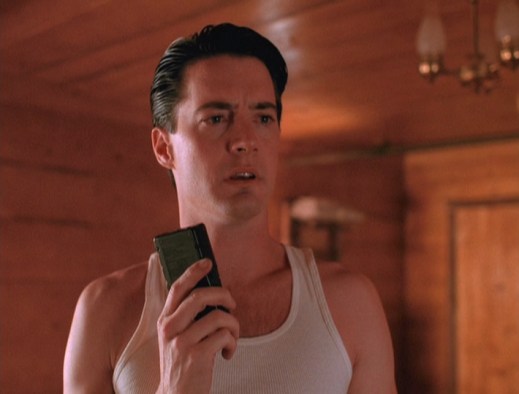

These forays into the extra-televisual possibilities of Twin Peaks began with the audiobook Diane…The Twin Peaks Tapes of Agent Cooper (1990). An example of what the new media scholar Henry Jenkins and others have labeled “transmedia storytelling,” the Diane tape provided marketers with another way to cash in on the Twin Peaks craze, and fans of the show a means to feed their appetite for FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper, aka Kyle Maclachlan’s Grammy nominated voice praising the virtues of the Double R Diner’s cherry pie.

Based on the reminders Cooper recorded into his “Micro-Mac pocket tape recorder” on the show, the cassette tape featured 38 reports of various lengths that warned listeners about the fishy taste of coffee and wondered “what really went on between Marilyn Monroe and the Kennedys.” As on the program, each audio note was addressed to Diane, whose off-screen and silent identity remained ambiguous. For the film and audio critic Michel Chion, Diane is an abstraction, or the Roman goddess of the moon. Others claim “Diane” is Cooper’s pet name for his recorder. The producers delivered their official line in the 1991 book The Autobiography of Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes, “as heard by Scott Frost,” (the brother of Lynch’s co-creator), where Cooper says, “I have been assigned a secretary. Her name is Diane. I believe her experience will be of great help.”

Whatever her identity, on the show Diane became the motive for Cooper’s voice recordings, and these scenes laid the groundwork for the audiobook. However, unlike the traditional audiobook, which reads a written text in its entirety, Cooper’s audio diary cuts away parts of the story, and includes additional notes and sounds not heard on the show.

The result is something like a voiceover version of Twin Peaks. And without the camera following the lives of the other characters, listeners can only experience the world of Twin Peaks as Diane would: through the recordings alone. Strangely, the inability to hear anything more than Cooper’s recordings opens up a new dimension: even as eavesdroppers we come closer to understanding Diane’s point of audition, the point towards which Cooper speaks in the first place.

Back on the show, Cooper’s notes to Diane track his movements as he tries to solve the mystery of who killed the Twin Peak’s prom queen Laura Palmer. Strangely—and not much isn’t strange in Lynch’s work— in some sense this mystery has already been solved by the show’s second episode, where Laura whispers the name of her killer to Cooper in a dream.

.

.

However, Laura’s whisper remains inaudible to the audience, and Cooper forgets what she said when he wakes up in the next episode. Much of the remainder of the program, full of Cooper’s reports to Diane, was spent trying to hear Laura’s voice. Thus, Diane, the off-screen and silent listener, became the narrative opposite to Laura, whose prom queen photograph closed each episode, and whose voice became the show’s central fetish object. Moreover, this silent relationship changes how the audience hears Cooper’s voice. Rather than a chance to relish in its sound, Cooper makes his recordings because of Laura’s voice from the grave, and directs them to Diane’s ears alone. In other words, Cooper and his recordings become a conduit to Laura/Diane rather than a solipsistic memoir about his time in Twin Peaks.

This triangulation becomes more obvious, if no less complicated in a typically labyrinthine Lynchian plot twist. As I mentioned, the Diane tape makes Cooper’s reports into a kind of voiceover. Critics have interpreted them as a parody of film noir, a genre whose history Ted Martin argues in his dissertation is defined by the relationship between voiceover and death: “Noir’s speaking voice moves from being on the verge of death to being in denial of death to emanating immediately, as it were, from the world of the dead itself.” Fascinated by this history, Lynch tweaks it through the introduction of a mina bird, famed for its capacity to mimic human voices. Discovered in a cabin at the end of episode 7, season 1, the police find the bird’s name—Waldo—in the records of the Twin Peaks veterinarian, Lydecker. The combined names—Waldo Lydecker—happen to identify the attempted murderer of Laura Hunter responsible for the voiceover in Otto Preminger’s classic noir film Laura (1944). On Twin Peaks, Cooper’s voice-activated dictaphone records Waldo the bird’s imitation of Laura Palmer’s last known words, which also happen to be Waldo’s last words, as he is shot by one of the suspects in Laura’s death.

If we follow this convoluted path of listening, we can trace a mediated circuit—from Laura to Waldo to Cooper’s voice recorder—which locates the voice of the (doubled) dead in the Dictaphone, thereby returning that voice to its noir origins in another classic of the genre: Double Indemnity (1944) (see SO! Editor’s J. Stoever-Ackerman’s take on the Dictaphone in this film here). More than a mere game of allusions, this scene substitutes Cooper’s voice with the imitation of Laura’s voice, inverting the noir tradition by putting the victim’s testimony on tape. And yet, while Waldo tantalizes the audience with an imitation of the sound of Laura’s voice, it ultimately only reminds the listener of the silent voice: Laura’s voice in Cooper’s dream.

The longer this voice remained out of range of the audience’s ears, the more it produced other voices—from Cooper’s recordings to Waldo to the dwarf in the Red Room.

Eventually, however, the trail of tape and sound it left behind ended with the amplification of Laura’s whisper, which became as much the “voice of the people” as Laura’s voice. After all, ABC instructed Lynch and Frost to answer the show’s instrumental mystery (“Who killed Laura Palmer?”) because of worries about the program’s declining ratings 14 episodes after Laura’s first inaudible whisper. The audience’s entrance into the show through the mediation of marketers mimicked the idea behind the Dianetape, but with a crucial difference: now the audience tuned in to hear their own collective voice, rather than to hear what and how Diane heard. Laura’s audible voice was audience feedback. It was the voice they called for through the Nielsen ratings. The image of her voice, on the other hand, was an invitation to listen. And Cooper’s voice-activated recorder, left on his bedside, placed in front of Waldo, or spoken into throughout the show remained an open ear, a gateway to an inaudible world called Diane. Although critics and Lynch himself have compared the elusive director to Cooper, perhaps its Diane who comes closest to representing Lynch as a “sound-man.”

David Lynch, August 10, 2008 by Flickr User titi

—

Tom McEnaney is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Cornell University. His work focuses on the connections between the novel and various sound recording and transmission technologies in Argentina, Cuba, and the United States. He is currently at work on a manuscript tentatively titled “Acoustic Properties: Radio, Narrative, and the New Neighborhood of the Americas.”

Recent Comments