Sounds of Home

Last month, I braved hail, snow, and just about every kind of plague-like spring weather to hear Karen Tongson’s talk at Cornell about her soon-to-be-released book, Relocations: Emergent Queer Suburban Imaginaries (NYU Press’s Sexual Cultures Series). Karen’s project remaps U.S. suburban spaces as brown, immigrant, and queer, thus relocating the foundations of both queer studies and urban studies. While not a part of the “dykeaspora” of color that Karen deftly details, I am in solidarity with the lives she traces and the soundscapes she amplifies more passionately than Lloyd Dobler with his boom box.

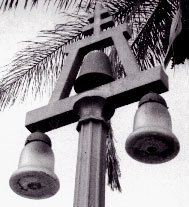

After all, Karen and I grew up together in the dusty, palm-tree lined streets of Riverside, California, meeting at Sierra Middle School and plotting our way the hell out of Dodge. . .only to later realize that our mutual plottings were really survivings—and a hell of a lot of fun—and the Riv—with its raincrosses and dry riverbeds, lifted trucks and low riders—would stay with us wherever we went.

After all, Karen and I grew up together in the dusty, palm-tree lined streets of Riverside, California, meeting at Sierra Middle School and plotting our way the hell out of Dodge. . .only to later realize that our mutual plottings were really survivings—and a hell of a lot of fun—and the Riv—with its raincrosses and dry riverbeds, lifted trucks and low riders—would stay with us wherever we went.

Since leaving Ithaca—Karen’s voice still warm in my ears like it used to be when tying up our parent’s pre-call-waiting phone lines—I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the way in which Relocations also reimagines the power of music. For Karen, music can help us know and love who we are more deeply, to enable us to “make do” with what we have been given in a way that liberates rather than incarcerates. Music is not just about “the differences it makes audible” (as Josh Kun writes in Audiotopia) but also, as Karen argues, about the ways in which sound gives us back to ourselves.

For example, a song that is spliced into Karen and I’s mutual musical DNA is “There is a Light that Never Goes Out” by The Smiths, (from 1986’s The Queen is Dead). Its various revolutions—both on turntables and in life choices—have affected us profoundly. In “The Light that Never Goes Out: Butch Intimacies and Sub-Urban Socialibilities in ‘Lesser Los Angeles,’” Karen uses the song as an affective touchstone for the ways in which sound can create “queer sociability, affinity, and intimacy” (355) while providing sonic moments of “self- and mutual-discovery” (360) and mediating relationships of place, power, pleasure, and privilege.

Karen’s ideas have since helped me understand why I used to listen to the song over and over in my lonely yet womb-like suburban bedroom, as if it were revelation and incantation. As I struggled with issues—identity and otherwise—Morrissey’s silken voice had the power to sound out the shape of my most secret wounds and simultaneously soothe them. Although I now know I am not alone in this, I thought I was back then, alone and waiting for someone to:

“Take me out tonight

where there’s music and there’s people

who are young and alive.”

In a now slightly-embarrassing Anglophilic phase—this was also around the time I was reading The Adrian Mole Diaries, watching My Fair Lady with Karen, and exchanging mixtapes with my British penpal—the Smiths were part and parcel of an England that I imagined as a long lost home. The U.K.’s pop cultural exports made it seem so much more tolerant of misfits of all kinds, let alone more temperate than SoCal for black turtlenecks and Doc Martens. At the time, I thought I was listening to difference—to the most remote space imaginable from the sweltering hothouse of Riverside—but Karen’s work reveals that I was really hearing the maudlin voice of my own longing, the jangly chords of my own desire, the oddball rhythms of my own heart.

I finally got myself to the actual England years later, thanks to the wonders of credit-card leveraged conferencing in destination locations. After the conference—at which I was, ironically, presenting on Los Angeles—I had the pleasure of spending a damp, foggy day record-shopping my way through brick-bound Nottingham. While I was gleefully flipping through velvety fields of plastic covers and comparing American imports with their UK counterparts, “There is a Light that Never Goes Out” came on the shop’s PA. With the first flare of guitar, I looked up from the record bins, startled by the warm recognition I felt at the sound of “home.”

At the time, I remember thinking that my thirteen-year-old self would be totally geeked out. However, I harbor little nostalgia for the volatile claustrophobia of my lonely tweenhood. Karen would describe my flash of recognition as “remote intimacy,” an asynchronous experience of popular culture across virtual networks of desire, a way of “imagining our own spaces in connection with others.”

Singing along for the thousandth time to Morrissey’s bittersweet grain, I realized that I wasn’t listening to my past in that record shop, but rather my thirteen-year-old self had been hearing the future in her bedroom. Dreaming of England had given her a way to grapple with the pains that ultimately produced my deepest longings: to overcome the “strange fears that gripped” me, to one day be able take myself “anywhere, anywhere,” and to feel the “light” of a love that would “never go out.”

It had taken a 5500 mile plane ride for me to realize that “home” was, in fact, a feeling of arrival rather than site of destination . . .and I couldn’t wait to get back to L.A. to give my homegirl Karen a call.

“There is a light that never goes out

There is a light that never goes out

There is a light that never goes out

There is a light and it never goes out. . .”

JSA

Gendered Ears

While there is a rich discussion in cultural studies about gendered representation in popular music, there remains very little about gendered listening experiences—or, more accurately—gendered perceptions of other’s listening experiences. Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies, one of the newest offerings from Duke’s Refiguring American Music series, makes promising headway in this direction, initiating a conversation about the way in which various types of listening practices—that of fans, musicians, and critics—are coded in the largely male dominated world of jazz. In popular music, however, this conversation has remained more nascent. As a female practitioner in the field with multiple identities—fan, vinyl collector, academic critic, consumer, blogger—it is uncomfortable how frequently I find people making very circumspect and circumscribed assumptions about the way in which I listen to music.

I have been collecting vinyl since the days when it was just called “buying records.” My first purchase at age 5, made via my Dad, was The GoGos’ Beauty and the Beat, which I still own, now carefully tucked into a plastic sleeve. And, thanks to my Dad’s gentle lesson in how to handle vinyl, it isn’t in very bad shape, either. Record collecting was a thrill my father shared with me, creating a connection between us that sometimes held when other bonds were endangered. No matter what, I always wanted to call him and tell him when I finally found a mint copy of Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall at a thrift store or Prince’s Purple Rain with the poster still inside.

I have been collecting vinyl since the days when it was just called “buying records.” My first purchase at age 5, made via my Dad, was The GoGos’ Beauty and the Beat, which I still own, now carefully tucked into a plastic sleeve. And, thanks to my Dad’s gentle lesson in how to handle vinyl, it isn’t in very bad shape, either. Record collecting was a thrill my father shared with me, creating a connection between us that sometimes held when other bonds were endangered. No matter what, I always wanted to call him and tell him when I finally found a mint copy of Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall at a thrift store or Prince’s Purple Rain with the poster still inside.

A number of weeks ago, I was on a routine summer Saturday morning mission: trolling the yard sales in my neighborhood for kid’s stuff, used books, and vinyl. While I never expect to find the holy grail of record albums at a yard sale, I am always willing to flip through piles of Barbara Streisand, Eddie Rabbit, Billy Joel, and Herb Alpert in the hopes I might uncover it. Usually, I just end up taking in the ripe dusty smell and silently cursing the sad condition of the vinyl I find there, hating to leave even the most scratched-up Mantovani warping in the full summer sun. But you never know.

On this particular Saturday, I was vinyl hunting with my infant son strapped to my chest and had my dog, He Who Cannot Be Named, pulling at the leash. In effect, I had suburban motherhood written all over my body as I strained on my tip-toes to reach records at the back of the pile and whispered to my sleeping son about why I was so excited to find a Les Paul and Mary Ford record. In the midst of my record reveries, I overheard a man next to me begin telling the proprietor of the yard sale about his record collecting habit. He went on and on about how long he has been collecting, how many records he has, how he “just got back from buying a thousand records off a guy in Appalachin.”

My hackles were instantly raised by this conversation about record-size. I already felt a bit left out, as this man obviously chose to ignore the woman actually looking at the records in favor of the only other man around. Vinyl collecting remains an overtly male phenomenon, as Bitch Magazine discussed in their 2003 Obsession issue. Although I am embodied evidence that women do collect vinyl, I am used to being in the complete minority at record shows, music conferences, and dusty basement retail outlets and overhearing countless conversations just like this one. In spite of myself, I decided to jump in to the conversation. . I thought I would cast out a lifeline to my fellow vinyl junkie, as the yard sale guy was obviously not interested and just humoring the record geek in front of him in the hopes that he would cart away the entire stack. Plus, I miss geeking out with someone else who loves records. After a lifetime in urban California, I now live in a small town in Upstate New York. While the record bins are not so tapped out here, it is lonely going for a record head. So I said to him, “I collect records too. I can’t believe you found so many records in Appalachin.” My invitation down the path of geekdom, however, was rebuffed. “Oh,” he said, barely looking up, “yeah. It happens all the time.” And then back to yard sale guy.

I tried not to take it personally, but it became impossible after this same scene was re-enacted at four or five different houses down the block. This guy was like a cover version of the Ancient Mariner, compelled to tell man after man all about the size of his enlarging record collection, the beloved albatross around his neck: “Man, have you ever tried to move a thousand records all at one time? They are so heavy and they take up so much space!”

And, I was the invisible witness to his tale of obsession, love, and woe, silently flipping through records just a few steps ahead of him. That is ultimately how I knew he did not see me as an equal rival in the world of vinyl hunting—he let me get ahead and stay ahead in the bins, neither sneaking peeks at what I pulled or, fingers flying, moving faster and faster in the hopes of overtaking me. He just assumed that I, dog in hand and baby on chest, would pull complete crap.

My listening ears then, bear the weight of my gender and the limited ways in which women are expected to engage with music. Women remain perpetually pegged as teeny-bopper fan club leaders and screaming Beatle fans, perpetually deafening themselves to the “real music.” Despite the deft critiques of Norma Coates, Susan Douglas, and Angela McRobbie, in which the early Beatles audience is re-imagined as proto-feminist and teenaged girls’ bedrooms are viewed as sites of cultural competency rather than deaf consumerism, my female ears remain cast as those of a groupie but never an aficionado, as if the two are somehow mutually exclusive. Imagine the Ancient Mariner’s surprise when this vinyl mama plucked pristine copies of The Cure’s Faith, The Fania All Stars Live at Yankee Stadium, and Aretha Franklin’s Live at the Fillmore West right out from under his own blind ears.

–JSA

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments