The Better to Hear You With, My Dear: Size and the Acoustic World

Today the SO! Thursday stream inaugurates a four-part series entitled Hearing the UnHeard, which promises to blow your mind by way of your ears. Our Guest Editor is Seth Horowitz, a neuroscientist at NeuroPop and author of The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes the Mind (Bloomsbury, 2012), whose insightful work on brings us directly to the intersection of the sciences and the arts of sound.

Today the SO! Thursday stream inaugurates a four-part series entitled Hearing the UnHeard, which promises to blow your mind by way of your ears. Our Guest Editor is Seth Horowitz, a neuroscientist at NeuroPop and author of The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes the Mind (Bloomsbury, 2012), whose insightful work on brings us directly to the intersection of the sciences and the arts of sound.

That’s where he’ll be taking us in the coming weeks. Check out his general introduction just below, and his own contribution for the first piece in the series. — NV

—

Welcome to Hearing the UnHeard, a new series of articles on the world of sound beyond human hearing. We are embedded in a world of sound and vibration, but the limits of human hearing only let us hear a small piece of it. The quiet library screams with the ultrasonic pulsations of fluorescent lights and computer monitors. The soothing waves of a Hawaiian beach are drowned out by the thrumming infrasound of underground seismic activity near “dormant” volcanoes. Time, distance, and luck (and occasionally really good vibration isolation) separate us from explosive sounds of world-changing impacts between celestial bodies. And vast amounts of information, ranging from the songs of auroras to the sounds of dying neurons can be made accessible and understandable by translating them into human-perceivable sounds by data sonification.

Four articles will examine how this “unheard world” affects us. My first post below will explore how our environment and evolution have constrained what is audible, and what tools we use to bring the unheard into our perceptual realm. In a few weeks, sound artist China Blue will talk about her experiences recording the Vertical Gun, a NASA asteroid impact simulator which helps scientists understand the way in which big collisions have shaped our planet (and is very hard on audio gear). Next, Milton A. Garcés, founder and director of the Infrasound Laboratory of University of Hawaii at Manoa will talk about volcano infrasound, and how acoustic surveillance is used to warn about hazardous eruptions. And finally, Margaret A. Schedel, composer and Associate Professor of Music at Stonybrook University will help readers explore the world of data sonification, letting us listen in and get greater intellectual and emotional understanding of the world of information by converting it to sound.

— Guest Editor Seth Horowitz

—

Although light moves much faster than sound, hearing is your fastest sense, operating about 20 times faster than vision. Studies have shown that we think at the same “frame rate” as we see, about 1-4 events per second. But the real world moves much faster than this, and doesn’t always place things important for survival conveniently in front of your field of view. Think about the last time you were driving when suddenly you heard the blast of a horn from the previously unseen truck in your blind spot.

Hearing also occurs prior to thinking, with the ear itself pre-processing sound. Your inner ear responds to changes in pressure that directly move tiny little hair cells, organized by frequency which then send signals about what frequency was detected (and at what amplitude) towards your brainstem, where things like location, amplitude, and even how important it may be to you are processed, long before they reach the cortex where you can think about it. And since hearing sets the tone for all later perceptions, our world is shaped by what we hear (Horowitz, 2012).

But we can’t hear everything. Rather, what we hear is constrained by our biology, our psychology and our position in space and time. Sound is really about how the interaction between energy and matter fill space with vibrations. This makes the size, of the sender, the listener and the environment, one of the primary features that defines your acoustic world.

You’ve heard about how much better your dog’s hearing is than yours. I’m sure you got a slight thrill when you thought you could actually hear the “ultrasonic” dog-training whistles that are supposed to be inaudible to humans (sorry, but every one I’ve tested puts out at least some energy in the upper range of human hearing, even if it does sound pretty thin). But it’s not that dogs hear better. Actually, dogs and humans show about the same sensitivity to sound in terms of sound pressure, with human’s most sensitive region from 1-4 kHz and dogs from about 2-8 kHz. The difference is a question of range and that is tied closely to size.

Most dogs, even big ones, are smaller than most humans and their auditory systems are scaled similarly. A big dog is about 100 pounds, much smaller than most adult humans. And since body parts tend to scale in a coordinated fashion, one of the first places to search for a link between size and frequency is the tympanum or ear drum, the earliest structure that responds to pressure information. An average dog’s eardrum is about 50 mm2, whereas an average human’s is about 60 mm2. In addition while a human’s cochlea is spiral made of 2.5 turns that holds about 3500 inner hair cells, your dog’s has 3.25 turns and about the same number of hair cells. In short: dogs probably have better high frequency hearing because their eardrums are better tuned to shorter wavelength sounds and their sensory hair cells are spread out over a longer distance, giving them a wider range.

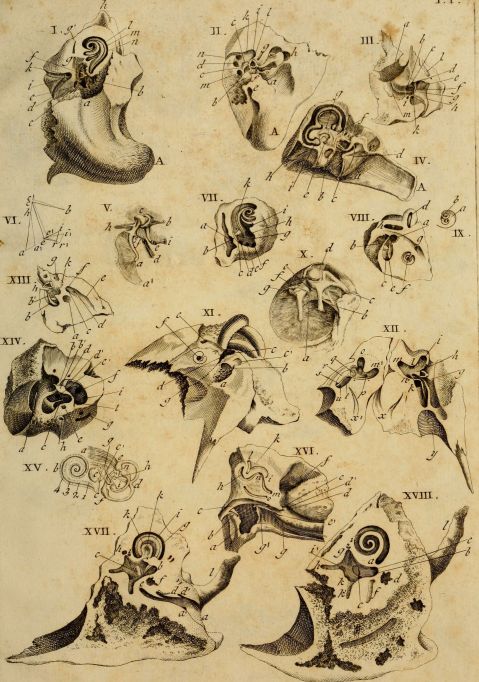

Interest in the how hearing works in animals goes back centuries. Classical image of comparative ear anatomy from 1789 by Andreae Comparetti.

Then again, if hearing was just about size of the ear components, then you’d expect that yappy 5 pound Chihuahua to hear much higher frequencies than the lumbering 100 pound St. Bernard. Yet hearing sensitivity from the two ends of the dog spectrum don’t vary by much. This is because there’s a big difference between what the ear can mechanically detect and what the animal actually hears. Chihuahuas and St. Bernards are both breeds derived from a common wolf-like ancestor that probably didn’t have as much variability as we’ve imposed on the domesticated dog, so their brains are still largely tuned to hear what a medium to large pseudo wolf-like animal should hear (Heffner, 1983).

But hearing is more than just detection of sound. It’s also important to figure out where the sound is coming from. A sound’s location is calculated in the superior olive – nuclei in the brainstem that compare the difference in time of arrival of low frequency sounds at your ears and the difference in amplitude between your ears (because your head gets in the way, making a sound “shadow” on the side of your head furthest from the sound) for higher frequency sounds. This means that animals with very large heads, like elephants, will be able to figure out the location of longer wavelength (lower pitched) sounds, but probably will have problems localizing high pitched sounds because the shorter frequencies will not even get to the other side of their heads at a useful level. On the other hand, smaller animals, which often have large external ears, are under greater selective pressure to localize higher pitched sounds, but have heads too small to pick up the very low infrasonic sounds that elephants use.

Audiograms (auditory sensitivity in air measured in dB SPL) by frequency of animals of different sizes showing the shift of maximum sensitivity to lower frequencies with increased size. Data replotted based on audiogram data by Sivian and White (1933). “On minimum audible sound fields.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 4: 288-321; ISO 1961; Heffner, H., & Masterton, B. (1980). “Hearing in glires: domestic rabbit, cotton rat, feral house mouse, and kangaroo rat.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 68, 1584-1599.; Heffner, R. S., & Heffner, H. E. (1982). “Hearing in the elephant: Absolute sensitivity, frequency discrimination, and sound localization.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 96, 926-944.; Heffner H.E. (1983). “Hearing in large and small dogs: Absolute thresholds and size of the tympanic membrane.” Behav. Neurosci. 97: 310-318. ; Jackson, L.L., et al.(1999). “Free-field audiogram of the Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata).” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 106: 3017-3023.

But you as a human are a fairly big mammal. If you look up “Body Size Species Richness Distribution” which shows the relative size of animals living in a given area, you’ll find that humans are among the largest animals in North America (Brown and Nicoletto, 1991). And your hearing abilities scale well with other terrestrial mammals, so you can stop feeling bad about your dog hearing “better.” But what if, by comic-book science or alternate evolution, you were much bigger or smaller? What would the world sound like? Imagine you were suddenly mouse-sized, scrambling along the floor of an office. While the usual chatter of humans would be almost completely inaudible, the world would be filled with a cacophony of ultrasonics. Fluorescent lights and computer monitors would scream in the 30-50 kHz range. Ultrasonic eddies would hiss loudly from air conditioning vents. Smartphones would not play music, but rather hum and squeal as their displays changed.

And if you were larger? For a human scaled up to elephantine dimensions, the sounds of the world would shift downward. While you could still hear (and possibly understand) human speech and music, the fine nuances from the upper frequency ranges would be lost, voices audible but mumbled and hard to localize. But you would gain the infrasonic world, the low rumbles of traffic noise and thrumming of heavy machinery taking on pitch, color and meaning. The seismic world of earthquakes and volcanoes would become part of your auditory tapestry. And you would hear greater distances as long wavelengths of low frequency sounds wrap around everything but the largest obstructions, letting you hear the foghorns miles distant as if they were bird calls nearby.

But these sounds are still in the realm of biological listeners, and the universe operates on scales far beyond that. The sounds from objects, large and small, have their own acoustic world, many beyond our ability to detect with the equipment evolution has provided. Weather phenomena, from gentle breezes to devastating tornadoes, blast throughout the infrasonic and ultrasonic ranges. Meteorites create infrasonic signatures through the upper atmosphere, trackable using a system devised to detect incoming ICBMs. Geophones, specialized low frequency microphones, pick up the sounds of extremely low frequency signals foretelling of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. Beyond the earth, we translate electromagnetic frequencies into the audible range, letting us listen to the whistlers and hoppers that signal the flow of charged particles and lightning in the atmospheres of Earth and Jupiter, microwave signals of the remains of the Big Bang, and send listening devices on our spacecraft to let us hear the winds on Titan.

Here is a recording of whistlers recorded by the Van Allen Probes currently orbiting high in the upper atmosphere:

When the computer freezes or the phone battery dies, we complain about how much technology frustrates us and complicates our lives. But our audio technology is also the source of wonder, not only letting us talk to a friend around the world or listen to a podcast from astronauts orbiting the Earth, but letting us listen in on unheard worlds. Ultrasonic microphones let us listen in on bat echolocation and mouse songs, geophones let us wonder at elephants using infrasonic rumbles to communicate long distances and find water. And scientific translation tools let us shift the vibrations of the solar wind and aurora or even the patterns of pure math into human scaled songs of the greater universe. We are no longer constrained (or protected) by the ears that evolution has given us. Our auditory world has expanded into an acoustic ecology that contains the entire universe, and the implications of that remain wonderfully unclear.

__

Exhibit: Home Office

This is a recording made with standard stereo microphones of my home office. Aside from usual typing, mouse clicking and computer sounds, there are a couple of 3D printers running, some music playing, largely an environment you don’t pay much attention to while you’re working in it, yet acoustically very rich if you pay attention.

.

This sample was made by pitch shifting the frequencies of sonicoffice.wav down so that the ultrasonic moves into the normal human range and cuts off at about 1-2 kHz as if you were hearing with mouse ears. Sounds normally inaudible, like the squealing of the computer monitor cycling on kick in and the high pitched sound of the stepper motors from the 3D printer suddenly become much louder, while the familiar sounds are mostly gone.

.

This recording of the office was made with a Clarke Geophone, a seismic microphone used by geologists to pick up underground vibration. It’s primary sensitivity is around 80 Hz, although it’s range is from 0.1 Hz up to about 2 kHz. All you hear in this recording are very low frequency sounds and impacts (footsteps, keyboard strikes, vibration from printers, some fan vibration) that you usually ignore since your ears are not very well tuned to frequencies under 100 Hz.

.

Finally, this sample was made by pitch shifting the frequencies of infrasonicoffice.wav up as if you had grown to elephantine proportions. Footsteps and computer fan noises (usually almost indetectable at 60 Hz) become loud and tonal, and all the normal pitch of music and computer typing has disappeared aside from the bass. (WARNING: The fan noise is really annoying).

.

The point is: a space can sound radically different depending on the frequency ranges you hear. Different elements of the acoustic environment pop up depending on the type of recording instrument you use (ultrasonic microphone, regular microphones or geophones) or the size and sensitivity of your ears.

![Spectrograms (plots of acoustic energy [color] over time [horizontal axis] by frequency band [vertical axis]) from a 90 second recording in the author’s home office covering the auditory range from ultrasonic frequencies (>20 kHz top) to the sonic (20 Hz-20 kHz, middle) to the low frequency and infrasonic (<20 Hz).](https://soundstudiesblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/figure3officerange.jpg?w=479&h=637)

Spectrograms (plots of acoustic energy [color] over time [horizontal axis] by frequency band [vertical axis]) from a 90 second recording in the author’s home office covering the auditory range from ultrasonic frequencies (>20 kHz top) to the sonic (20 Hz-20 kHz, middle) to the low frequency and infrasonic (<20 Hz).

Featured image by Flickr User Jaime Wong.

—

Seth S. Horowitz, Ph.D. is a neuroscientist whose work in comparative and human hearing, balance and sleep research has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and NASA. He has taught classes in animal behavior, neuroethology, brain development, the biology of hearing, and the musical mind. As chief neuroscientist at NeuroPop, Inc., he applies basic research to real world auditory applications and works extensively on educational outreach with The Engine Institute, a non-profit devoted to exploring the intersection between science and the arts. His book The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes the Mind was released by Bloomsbury in September 2012.

—

REWIND! If you liked this post, check out …

Reproducing Traces of War: Listening to Gas Shell Bombardment, 1918– Brian Hanrahan

Learning to Listen Beyond Our Ears– Owen Marshall

This is Your Body on the Velvet Underground– Jacob Smith

The Musical Flow of Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color

Welcome back to Sculpting the Film Soundtrack, SO!‘s new series on changing notions about how sound works in recent film and in recent film theory, edited by Katherine Spring.

Two weeks ago, Benjamin Wright started things off with a fascinating study of Hans Zimmer, a highly influential composer whose film scoring borders on engineering — or whose engineering borders on music — in many major Hollywood releases. This week we turn to the opposite end of the spectrum to a seemingly smaller film, Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color (2013), which has made quite a few waves among sound studies scholars and fans of sound design, even earning a Special Jury Prize for sound at Sundance.

To unpack the many mysteries of the film and explore its place in the field of contemporary filmmaking, we are happy to welcome musicologist and film scholar Danijela Kulezic-Wilson of University College Cork. Listen to Upstream Color through her ears (it’s currently available to stream on Netflix) and perhaps you’ll get a sense of why you’ll have to listen to it two or three more times. At least.

–nv

—

When Shane Carruth’s film Upstream Color was released in 2013, critics described it in various ways—as a body horror film, a sci-fi thriller, a love story, and an art-house head-scratcher—but they all agreed that it was a film “not quite like any other”. And while the film’s cryptic imagery and non-linear editing account for most of the “what the hell?” reactions (see here for example), I argue that the reason for its distinctively hypnotic effect is Carruth’s musical approach to the film’s form: he organizes the images and sounds according to principles of music, including the use of repetition, rhythmic structuring, and antiphony.

The resulting musicality of Upstream Color may not be surprising given that Carruth composed most of the score, and also, as Jonathan Romney has noted in Sight & Sound, Carruth has said on many occasions that he was hoping “people would watch this film repeatedly, as they might listen to a favourite album” (52). In this sense, Carruth (whose DIY toolkit also includes writing, directing, acting, producing, cinematography, and editing) joins the ranks of filmmakers such as Darren Aronofsky and Joe Wright who recognize that, despite our culture’s obsession with the cinematic and narrative aspects of “visual” media, music governs film’s deepest foundations.

Upstream Color is a story about a woman, Kris, who is kidnapped by a drug manufacturer (referred to in the credits as Thief) and contaminated with a worm that keeps her in a trance-like state during which the Thief strips her of all her savings. Kris is subsequently dewormed by a character known as the Sampler, who transfers the parasite into a pig that maintains a physical and/or metaphorical connection to Kris. Kris later meets and falls in love with Jeff who, we eventually discover, has been a victim of the same ordeal. Although the bizarreness of the plot has encouraged numerous interpretations, the film’s unconventional audio-visual language suggests that its story of two people who share supressed memories of the same traumatic experience shouldn’t be taken at face value, but rather serves as a metaphor for existential anxiety resulting from being influenced by unknown forces.

Such an interpretation owes as much to the film’s disregard for the rules of classical storytelling as it does to a formally innovative soundtrack, one that uses musicality as an overarching organizing principle. The fact that Carruth wrote the score and script simultaneously (discussed in the video below) indicates the extent to which music was from the beginning considered an integral part of the film’s expressive language. More importantly, as the scenes discussed in this post suggest, the musical logic of the film is even more pervasive than the style, role, and placement of the actual score.

Whereas feature films traditionally assign a central role to speech, allowing music and sound effects supporting roles only, Upstream Color breaks down the conventional soundtrack hierarchy, often reversing the roles of each constitutive element. For example, hardly any information in the film that could be considered vital to understanding the story is communicated through speech. Instead, images, sound, music, and editing–for which Carruth shares the credit with fellow indie director David Lowery–are the principal elements that create the atmosphere, convey the sense of the protagonists’ brokenness, and reveal the connection between the characters. At the same time, characters’ conversations are either muted or their speech is blended with music in such a way that we’re encouraged to focus on body language or mise-en-scène rather than trying to discern every spoken word. For example, Jeff and Kris’s flirting with one another during their initial meetings (at roughly 0.44.20-0.47.00 of the film) is conveyed primarily through gestures, glances, and fragmentary editing rather than speech, which would be more typical for this sort of narrative situation.

Further undercutting the significance of speech across the film is how the film has been edited to resemble the flow of music. For example, non-linear jumps in the narrative are often arranged in such a way as to create syncopated audio-visual rhymes. This technique is particularly obvious in the montage sequence in which Kris and Jeff argue over the ownership of their memories, whose similarities suggest that they were implanted during the characters’ kidnappings. In this sequence, both the passing of time and the recurrence of the characters’ argument is conveyed through the repetition of images that become visual refrains: Kris and Jeff lying on a bed, watching birds flying above trees, touching each other. Some of these can be seen in the film’s official trailer:

The scene’s images and sounds are fragmented into a non-linear assembly of pieces of the same conversation the characters had at different times and places, like the verses and the choruses of a song. Importantly, the assemblage is also patterned, with phrases like “we should go on a trip” and “where should we go?” heard in refrain. The first time we hear Jeff say “we should go on a trip” and suggesting that they go “somewhere bright”, his words are played in sync with the image of him and Kris lying on the bed. The following few shots, accompanied only by music, symbolize the “honeymoon” phase of their relationship: the couple kiss, hold hands, and walk with their hands around each other’s waists. A shift in mood is marked by the repetition of the dialogue, with Jeff again saying “we should go on a trip” – only this time, the phrase plays asynchronously over a shot of Jeff and Kris pushing a table into the house that they have moved into together. Finally, the frustration that starts infiltrating the characters’ increasingly heated arguments is alleviated by the repetition of the sentence “They could be starlings.” As it is spoken three times by both characters in an antiphonic exchange, the phrase emphasizes the underlying strength of their connection and gives the scene a rhythmic balance. Across this sequence, the musical organization of audio-visual refrains prompts us to recognize the psychic connection between Kris and Jeff, and even to begin to guess the sinister reason for it.

While speech in Upstream Color is often stripped of its traditional role as a principal source of information, sound and music are given important narrative functions, illuminating hidden connections between the characters. In one of the most memorable scenes, the Sampler is revealed to be not only a pig farmer but also a field recordist and sound artist who symbolizes the hidden source of everything that affects Kris and Jeff from afar. As we hear the sounds of the Sampler’s outdoor recordings merge with and emulate the sounds made and heard by Kris and Jeff at home and at work, the soundtrack eloquently establishes the connection between all three characters while also giving us a look “behind the scenes” of Kris’s and Jeff’s lives and suggesting how they are influenced from a distance.

In one sense, by calling attention to the very act of recording sound, the scene exposes how films are constructed, offering a reflexive glimpse into usually hidden processes of production. The implied idea here–that the visible and audible are products of not-so-obvious processes of formation–refers not only to the medium of film but also to the complexity of the inner workings of someone’s mind. Thus the Sampler’s role, his actions, and his relationship to Kris, Jeff, and other infected victims can be interpreted as a metaphor for the subconscious programming – all the familial, social and cultural influences – that all of us are exposed to from an early age. The Sampler is portrayed symbolically as the Creator, a force whose actions affect the protagonists’ lives without them knowing it. The fact that he is simultaneously represented as a sound artist establishes sound-making and musicality as the film’s primary creative principles.

Considering Carruth’s very deliberate departure from the conventions of even what David Bordwell calls “intensified” storytelling, it is fair to say that Upstream Color is a film that weakens the strong narrative role traditionally given to oral language. What is intensified here are the musical and sensuous qualities of the audio-visual material and a mode of perception that encourages absorption of the subtext (in other words, the metaphorical meaning of the film) as well as the text.

The musical organization of film form and soundtrack is no longer limited to independent projects such as Carruth’s Upstream Color. As I have shown elsewhere, musicality has become an extremely influential principle in contemporary cinema, acting as an inspiration and model for editing, camera movement, movement within a scene and sound design. Some of the most interesting results of a musical approach to film include Aronofsky’s “hip hop montage” in Pi (1998) and Requiem for a Dream (2000), Jim Jarmusch’s rhythmically structured film poems (The Limits of Control, 2009; Only Lovers Left Alive, 2013), the interchangeable use of musique concrète and environmental sound in Gus Van Sant’s Death Trilogy and films by Peter Strickland (Katalin Varga, 2009; Berberian Sound Studio, 2012); the choreographed mise-en-scène in Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina (2012); the musicalization of language in Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers (2012); and the foregrounding of musical material over intelligible speech in Drake Doremus’s Breathe In (2013). Given the breadth of these examples, it’s no exaggeration to say that filmmakers’ growing affinity for a musical approach to film is changing the landscape of contemporary cinema.

—

Danijela Kulezic-Wilson teaches film music, film sound, and comparative arts at University College Cork. Her research interests include approaches to film that emphasize its inherent musical properties, the use of musique concrète and silence in film, the musicality of sound design, and musical aspects of the plays of Samuel Beckett. Danijela’s publications include essays on film rhythm, musical and film time, the musical use of silence in film, Darren Aronofsky’s Pi, P.T. Anderson’s Magnolia, Peter Strickland’s Katalin Varga, Gus Van Sant’s Death Trilogy, Prokofiev’s music for Eisenstein’s films, and Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man. She has also worked as a music editor on documentaries, short films, and television.

—

All images taken from the film.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sound Designing Motherhood: Irene Lusztig & Maile Colbert Open The Motherhood Archives— Maile Colbert

Play it Again (and Again), Sam: The Tape Recorder in Film (Part One on Noir)— Jennifer Stoever

Animal Renderings: The Library of Natural Sounds— Jonathan Skinner

Recent Comments