(T)racing Mother Listening: W.E.B. Du Bois & Sigmund Freud

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter-Ényì, Austin Richey, Julie Beth Napolin, and Vanessa Valdés, move us toward a decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it. To start the series from the beginning, click here.

Readers, today’s post (the second of an interlocking trilogy of essays) by Julie Beth Napolin continues to echolocate Du Bois and Freud as lived contemporaries, exploring entangled notions of melancholic listening across the Veil.

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

In “Intimacy and Affliction,” Peter Coviello writes of W.E.B. Du Bois’ abiding, proto-psychoanalytic preoccupation with race’s “entanglements with virtually every aspect of intimate life” (4). Such entanglement demands, he suggests, a method both historical and psychoanalytic. Coviello recalls, for example, the work of Hortense Spillers who writes that Du Bois finds in the color line “radically different historical reasons” for such key psychoanalytic themes as the “look” than those to be discovered in the pages of Lacan (726).

While there’s much to say on this topic, I want to focus in particular on the contribution of Du Bois to a psychoanalytic theory of listening, showing how that contribution demands a renewed return of psychoanalysis, sexuality, and race to sound studies. Beginning to touch upon these questions, literary critic Joseph Flatley describes the intersection of politics and melancholia in Du Bois to argue for what he calls “affective mapping” in listening. For Du Bois, songs disclose the historicity of his feelings, bound to other people who feel and have felt like he does before (146), creating a transpersonal map. This disclosure, Flatley writes, “always beckons towards a potentially political effect,” an effect that is often “nascent and unrealized” (106). Such nascence, or what Sara Marcus calls “untimely feedback,” begins to explain why we listen to old songs in the present: old feelings are waiting for us to take them up in politically transformative ways. I will unfold this claim in this week’s post to conclude with an analysis of the politics of sound, gender, and sexuality in Barry Jenkins’ 2016 film, Moonlight.

Du Bois’ mode of presentation of word, sound, and melody in The Souls of Black Folk has been theorized by Alexander Weheilye as being akin to DJ samples cutting and mixing history and by Eric Sundquist as the elevation of a uniquely African American culture. In an earlier post in this series, “More Ancient Than Words,” Aaron Carter-Ényì argues that, in including melodies, Du Bois “entered the songs into a new literary and scholarly canon,” changing the concept of “the book.”

vinyl loves water, image by Flickr User Georgios Kaleadis

Beyond this work of canonization, which turns upon the existence of what Gilroy names the “Black Atlantic,” the materiality of Du Bois’ text discloses much concerning the suppressed contours of both race and the feminine in psychoanalytic theories of listening. It is difficult to separate these theories (particularly Chion’s, as Kaja Silverman makes plain in The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema) from Freud’s premise of a universal, male subject. In Freud’s theory of the Oedipal phase, the male child desires to supplant the father, and the mother—who is culturally forbidden from being seen in any way as being akin to or “like” the boy—emerges as the model of the proper object for heterosexual desire. But the pre-Oedipal phase is the opposite, defined by a closeness with the mother, often revealed in the language of cooing sounds they share. In other words, masculinity is culturally founded on the rejection of the feminine. Despite Silverman’s major contribution, this structure still remains essential for sound studies to deconstruct, particularly as it obscures other kinds of historical determinations that give shape to listening and the psychic life of sound in Du Bois’ text.

Psychoanalysis had been largely abandoned by the various “historical turns” in media studies. But it can only be recuperated in a Du Boisian fashion, that is, by the modes of listening made available by his text. Above all, the psychobiography indicated by Du Boisian listening is neither “universal” nor Oedipally determined—shaped by the destruction of the maternal— but rather historically and politically wrought by the specificity and ubiquity of the Middle Passage, or what Christina Sharpe names “being in the wake.”

“In the Wake,” image by Flickr User Sharonius Maximus

Unfolding the gendered afterlife of the Middle Passage has proved crucial for black feminism. Saidiya Hartman’s lyrical memoir of her experience as an African American woman traveling along the former routes of the Atlantic slave trade, for example, is defined by the feeling of what it is to “lose your mother.” This phrase contains many melancholic resonances, including the ideal of Africa (as a place of imaginary “return”), its phantasmatic, lost mother tongues, and fantasies of reunited kin in the midst of longing for “a new naming of things” (39). At the same time, Hartman suggests, the African American subject—whose name is derived from the slave owner—is “born with a blank space where a father’s name should be.” This blank space, its attendant forms of de-gendering, makes an imputed maternal inheritance of the black subject in the American cultural imaginary nothing less than a “monstrosity” (81).

In tension with these revelations, Sundquist’s magisterial To Wake the Nations argues that Du Bois’ textual presentation and formal strategies of pairing word and melody indicate racial amalgamation. Such a notion, however, is largely fraternal in its connotation. Indeed, the poetic epigraphs Du Bois calls upon are from white men, as many have critiqued. Flatley has shown how the “echo of haunting melody” is both historically and melancholically charged in Du Bois. We in sound studies can go further to describe how it is an acousmatic sound object. Such a claim involves intervening in the racially neutral terrain of the sound object to insist that it emanates in Du Bois’ memory from a black maternal position. This position makes the epigraphic space not so much an otherworldly union, but a violently charged, historical space that listens for the traces of miscegenation. It desires a place for the black maternal that could be articulated without also being repressed.

Where there is amalgamation, there is sexuality. Du Bois’ formal strategies, both conscious and unconscious, are radical because they indicate potential for a theory for a listening derived from or animated by a black feminine position.

***

To listen for the black maternal in Du Bois, then, involves returning to its most traumatic memory of song, one carried by his unnamed grandfather’s grandmother in the book’s final chapter, “The Sorrow Songs.” Whereas the opening epigraphs of Du Bois’s text provide us with bars of melody offered without comment, his final chapter is a sustained and nearly musicological analysis of song. The one amplifies silence, heightening the gap between reading, hearing, and understanding, the other produces cultural knowledge. At the core of “The Sorrow Songs” is the autobiographical memory of a song first heard in childhood. It is perhaps his earliest memory of song, though we can’t be sure.

Do ba – na co – ba, ge – ne me, ge – ne me!

Do ba – na co – ba, ge – ne me, ge – ne me!Ben d’ nu – li, nu – li, nu – li, nu – li, ben d’ le.

He recalls this melody, as sung by a Bantu woman seized by Dutch traders: “The child sang it to his children and they to their children’s children, and so two hundred years it has travelled down to us and we sing it to our children, knowing as little as our fathers what its words may mean, but knowing well the meaning of its music.” For Du Bois, the song remains a transmission that necessarily involves both a partial memory and a mode of overhearing, as if hearing from a distance. Du Bois “overhears” not because, like Freud’s Wolf Man, he stands at the threshold of a secret and clandestine threshold. Du Bois overhears because to receive the song in the New World is already to be traumatized, on the outside of some possibility of full transmission. Carter-Ényì describes how rhythms and “melodies may last longer than lyrics as cultural transmissions.” Melody in Du Bois provides “an alternate theory” of orality and literacy, one that privileges not a spoken oral tradition, but rather a survival of music, an aural tradition, as Carter-Ényì calls it, where melodies hold fast when language is “violently submerged.”

I want to fasten upon a different but related aural affect, not the one of immediate recognition (through which the song is passed down), but rather its attendant ambivalence and gaps. This gap—hearing without understanding— returns us to Souls as a displaced beginning of psychoanalytic modes of listening.

“Bubbles, Streams, and Waves.” Image by Flickr User Wolfgang Widener

According to Theodor Reik, Freud’s musically attuned student, Freud experienced an extreme distaste for music because an analytic trait bristled against something he couldn’t clearly theorize. When he did attend to the songs remembered by his patients, Freud suggested that only the words mattered. Bucking his master, Reik instead privileged the sound of a song, a tune and its affective valences, noting that “haunting melodies”—the same phrase used by Du Bois to describe sorrow songs as they echo on the other side of the Middle Passage—must be listened to with what Reik called a “third ear.” Insisting that two ears already too many, Jacques Lacan resists Reik’s emphasis upon listening for meaning to suggest that an analyst instead “listen for sounds and phonemes, words, locutions, and…not forgetting pauses, scansions, cuts” (394). Even transcriptions of patient speech, Lacan says, must include these as the basis of “analytic intuition.”

The way the analyst listens beyond meaning resonates with Du Bois who was already listening to, repeating, and writing down the Bantu song without knowing what the words mean, nevertheless “knowing,” as it were, the meaning, ascribing to it great psychological importance. In the language of sound studies, “Do ba – na co – ba” is a sound object. Something of it is acousmatic, arriving as a sound separated from source. But the acousmatic is largely apolitical in its orthodox, Schaefferian conception. Schaeffer deems the sound object to be separable from its ecology, which would include not only ideology and the social, but race and history. In contrast, we learn from Du Bois that an acousmatic situation can rest upon historically determined partial memory. “Do ba – na co – ba” is sung in a so-called “mother tongue,” but this tongue is unknowable, unretrievable by Du Bois (the words he remembers as sounds have yet to be translated by historians).

We can’t forget that, like Du Bois, Freud died in exile (the one in Ghana, American citizenship revoked, the other in London, escaping persecution). When Reik describes the haunting melody, he begins with the experience of mourning. What he doesn’t say is that he himself, writing in English in America, was in émigré from war. The émigré is not the captive, and immigration is not forced migration of the Middle Passage. My point is that the position of racialized listening that is submerged in Freud is the avowed place of beginning in Du Bois, allowing him to address head on the historical and political conditions of listening, even though he can’t totally compass their sexual charge. He is listening for a new kind of political subject whose dictum is “lose your mother.”

Coast off Accra, Ghana, Image by Flickr User Fellfromatree

Importantly, “Do ba – na co – ba” is not part of the pre-Oedipal maternal effluence of sound and rhythm that Julia Kristeva famously calls the “semiotic chora.” Part of the content of the song is defined by being missing, seized, and surviving (rather than simply coming and going). Nor is it structured by the Oedipal desire to supplant the father and have the desire mother. Above all, Du Bois turns to this intensely personal memory of song to posit an individual coming into formation through a memory of song that is collective. These songs are both his and belong to others. Hearing the song involves affective mapping, or understanding oneself as being more than oneself (which we will find in part three of this essay) is the crux of sound and music in Moonlight.

Du Bois doesn’t begin the book with this memory of a Bantu woman’s crooning, but rather ends with it. By relocating the (personal) primal scene to the end, he redefines the political possibility for its epistemological rupture. This beginning releases the reader back into the world as a listener whose ears are now pricked, that is, alert to the historical injuries that sustain subject formation. In this way, the formal elision of the song animates the autobiographical locus of the book, its subject and its self. In other words, it is a locus that has to be displaced in order to be represented. This displacement is not merely symbolic, owing to the structure of language as such, but to or the real displacement of exile, the forcible entry into an imperial or colonizing language while one’s mother tongue is extracted, stolen, or erased.

Door of No Return, Cape Coast Castle, Ghana, Image by Flickr User Greg Neate

Here, I point to black feminism and its transformative use of psychoanalysis. Spillers begins her intensely psychoanalytic essay, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” with Du Bois’ prediction for a 20th century that will be defined by “the problem of the color line.” But she argues the color line is a “spatiotemporal configuration” to which must be added another and weightier thematic: the revelation of the figure of the “black woman,” i.e. a “particular figuration of the split subject that psychoanalytic theory posits” (65). This split—between the “I” and the “me”—is defined for Lacan by the entry into language. The Freudian primal scene is triangulated by the threat of castration that underwrites the boy’s entry into language. Though imaginary, it was nonetheless literal, localized in genital fantasies. For Lacan, castration is instead a more a generalized cut between the signifier and signified, the conscious and the unconscious. No one, male or female, escapes this cut, and the formation of the “I,” the subject, is contingent upon the separations and losses that language first negotiates. The infant first learns words to articulate pleasure and pain, its separation from things. We forever have the word because we don’t have the thing.

When Spillers takes up psychoanalysis it is to make the radical claim that the New World is “written in blood.” There is not the fantasy of castration, but rather a history of “actual mutilation, dismemberment, and exile,” a “theft of the body” that severs it from its motive, will, and desire (67). Spillers insists not on crimes against the body (a more traditional category in psychoanalysis), but what she calls the “flesh” in its capacity to be harmed. Flesh forms the basis of a central distinction between captive and liberated subject-positions. By the primary narrative of flesh, she continues, “we mean its seared, divided, ripped-apartness, riveted to the ship’s hole, fallen, or ‘escaped’ overboard.”

Lacan’s move is de-literalize castration in favor of structure; Spillers (poststructuralist) move is to re-literalize it, but without losing the insight that the cut is language itself, the separation between word and thing. Spillers’ point, however, is that psychoanalysis is incomplete until it can think these transhistorical questions. By this same token, I would argue, sound studies remains incomplete if it cannot transform what we think we are listening for in language. Lacan insists that the word is an irremediable cut or severance from a thing that it nonetheless brings into being through naming. Sound studies misrecognizes itself if it thinks that sound isn’t precisely what is to be located and listened for through the cut between word and thing.

The memory of “Do ba – na co – ba” is both sung and heard from within that cut. These words (that are also not words) are the coming into being of a thing that cannot be named, or is sounded out rather than named. We are suddenly placed into a terrain—and mode of listening—not totally familiar to the origins of psychoanalysis, unless we include Du Bois. We enter into real implications for the primal scene. At the beginning of Souls, Du Bois elliptically notes “the red stain of bastardy,” which designates the rape of black women by white men. Is not the trauma of this stain indirectly registered by Du Bois when listening to “Do ba – na co – ba,” as the crooning of a kidnapped woman? The meaning of its sound is “well understood”—but never put into words. This unnamed Bantu woman’s crooning is a song of becoming violently undifferentiated, a thing, alienated, and forced out of language: it is a song of the flesh. In this way, Du Bois’ political subject position cannot be fully separated from the flesh of the past whose searing and ripping “transfers,” Spillers suggests, across generations. With Du Bois, then, we encounter a subject and bodily ego with memories that are not entirely personal, but rather transpersonal.

For Du Bois, the memory of listening is animated by the fantasy of belonging to a lost language out of which his authorial “voice” and with it, the sorrow songs, emerge. The place of the mother’s voice in psychoanalysis is often one that sweetly echoes back and repeats the self to itself. That is why we are drawn to lullabies; they sonically contain and affirm us. Barthes famously writes of the “grain of the voice.” “That is what the “grain” would be: the materiality of the body speaking its mother tongue . . . [Emphasis mine]” (270). But this body is not the flesh. The grain is the voluptuousness of a voice speaking its “mother tongue.”

“Foam” by Flickr User Melissa Emmons

It is not that Du Bois is without voluptuous memories of a mother’s voice, but rather that he elevates a different kind of auditory heritage of the self. He writes of the sorrow songs as “some echo of haunting melody.” There are two orders of remove in what is presupposed by Barthes to be a perfectly reflexive scene. It is not that Du Bois did not as an infant experience this conjectured scene, but that it is doubled by another that does not enter into psychoanalytic discourse without its completion by black feminism, postcolonialism, and other discourses that begin from the premise of historical trauma and stolen mother tongues.

Du Bois was able to listen for what Freud repressed. Du Bois writes down not only the melody as he remembers it, as it has been passed down to him, but also the sounds of her words in Romanized letters that approximate her phonemes. The melody has persisted in spite of the mystery of the words. But what becomes apparent in their approximation, as phonemes, is both retention and loss. The Bantu woman sings in a lost mother tongue; singing, she is in the midst of being forcibly taken away from language, and the song acts as a trace.

Next week, Napolin’s third essay will further explore the psychoanalytic listening Du Bois enacts via The Souls of Black Folk through a reading of Barry Jenkins’ “stunningly lyrical and psychologically complex coming-of-age film, Moonlight,” and its use of wave-sound aural imagery that “continually marks a desire for “return” to maternal undifferentiation and oneness, and yet. . .provides the space for two embodied memories that cannot be compassed by traumatic separation.”

—

Julie Beth Napolin is Assistant Professor of Literary Studies at The New School, a musician, and radio producer. She received a PhD in Rhetoric from the University of California, Berkeley. Her work participates in the fields of sound studies, literary modernism and aesthetic philosophy, asking what practices and philosophies of listening can tell us about the novel as form. She served as Associate Editor of Digital Yoknapatawpha and is writing a book manuscript on listening, race, and memory in the works of Conrad, Du Bois, and Faulkner titled The Fact of Resonance. Her work has appeared in qui parle, Fifty Years After Faulkner (ed. Jay Watson and Ann Abadie), and Vibratory Modernism (ed. Shelley Trower and Anthony Enns).

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“A Sinister Resonance”: Joseph Conrad’s Malay Ear and Auditory Cultural Studies–Julie Beth Napolin

“Scenes of Subjection: Women’s Voices Narrating Black Death“–Julie Beth Napolin

Listening to and as Contemporaries: W.E.B. Du Bois & Sigmund Freud–Julie Beth Napolin

Share this:

- by Wanda Alarcon

- in American Studies, Article, Chican@/Latin@ Studies, Chicana Soundscapes Forum, Dance/Movement, Fandom/Fan Studies, Games/Gaming, Gender, History, Listening, Literature, Memoir, Place and Space, Poetry/Poets, Popular Music Studies, Queer Studies, Sexuality, Sound Studies, Soundscapes, Technology, Time

- 6 Comments

“Oh how so East L.A.”: The Sound of 80s Flashbacks in Chicana Literature

For the full intro to the forum by Michelle Habell-Pallan, click here. For the first installment by Yessica Garcia Hernandez click here. For the second post by Susana Sepulveda click here.

For the full intro to the forum by Michelle Habell-Pallan, click here. For the first installment by Yessica Garcia Hernandez click here. For the second post by Susana Sepulveda click here.

The forum’s inspiring research by scholars/practioners Wanda Alarcón, Yessica Garcia Hernandez, Marlen Rios-Hernandez, Susana Sepulveda, and Iris C. Viveros Avendaño, understands music in its local, translocal and transnational context; and insists upon open new scholarly imaginaries. . .

Current times require us to bridge intersectional, decolonial, and gender analysis. Music, and our relationship to it, has much to reveal about how power operates within a context of inequality. And it will teach us how to get through this moment. –MHP

—

A new generation of Chicana authors are writing about the 1980s. An ‘80s kid myself, I recognize the decade’s telling details—the styles and fashions, the cityscapes and geo-politics, and especially the sounds and the music. Reading Chicana literature through the soundscape of the 80s is exciting to me as a listener and it reveals how listening becomes a critical tool for remembering. Through the literary soundscapes created by a new generation of Chicana authors such as Estella Gonzalez, Verónica Reyes, and Raquel Gutiérrez, the 1980s becomes an important site for hearing new Chicana voices, stories, histories, representations, in particular of Chicana lesbians.

Reading across Gonzalez’s short story, “Chola Salvation,” Reyes’s Chopper! Chopper! Poetry from Bordered Lives; and Gutiérrez’s play, “The Barber of East L.A,” this post activates the concept of the “flashback” to frame the 1980s as a musical decade important for exploring Chicana cultural imaginaries beyond its ten years. In Gonzalez’s “Chola Salvation,” for example, Frida Kahlo and La Virgen de Guadalupe appear dressed as East Los cholas speaking Pachuca caló and dispensing valuable advice to a teen girl in danger. The language of taboo and criminality is transformed in their speech and a new decolonial feminist poetics can be heard. In Reyes’s Chopper! Chopper!, Chicana lesbians – malfloras, marimachas, jotas, y butch dykes – strut down Whittier Boulevard, fight for their barrio, take over open mic night and incite a joyous “Panocha Power” riot, and make out at the movies with their femme girlfriends. Gutiérrez’’s “Barber of East L.A” recovers forgotten butch Chicana histories in the epic tale of a character called Chonch Fonseca, inspired by Nancy Valverde, the original barber of East Los Angeles. A carefully curated soundtrack amplifies her particular form of butch masculinity. These decolonial feminist ‘80s narratives signal a break from 1960s and ‘70s representations of Chicanas/os and introduce new aesthetics and Chicana/x poetics for reading and hearing Chicanas in literature, putting East L.A. on the literary map.

East LA Valley, 2010, by Flickr User James (CC BY 2.0)

Gonzalez, Reyes, and Gutiérrez’s work also use innovative sonic methods to demonstrate themes of feminist of color coalition and solidarity and represent major characters whose desires and actions transgress normative gender and sexuality. All three contain so many mentions of music that operate beyond established notions of intertextuality, referencing oldies, boleros, and alternative 80s music as a soundtrack that actually transform these works into unexpected sonic archives. Through the 80s soundscapes that music activates, these authors’ work shifts established historical contexts for reading and listening: there was a time before punk, and after punk, and this temporality sounds in Chicana literature.

Alice Bag in The Decline of Western Civilization (1981). Still by Jennifer Stoever

If the classic documentary film The Decline of Western Civilization by Penelope Spheeris was meant to give coverage to the Los Angeles neglected by mainstream music journalists, it also performs an important omission that leaves Chicano viewers searching for a mere glimpse of “a few brown Mexican faces,” as Reyes writes in her poem “Torcidaness.” Among the bands featured–most male fronted–the film captures an electric performance by Chicana punk singer Alice Bag, née Alicia Armendariz. In contrast to the other musicians in jeans, bare torsos, and, combat boots, Bag is visually stunning and glamorous. She dressed in a fitted pink dress reminiscent of the 1940s pachuca style; she wears white pointed toe pumps, her hair is short and dark, her eye and lip makeup is strong and impeccable. In the four brief minutes the band is on camera Bag sings in a commandingly deep voice, slowly growling out the words to the song “Gluttony” and before the tempo picks up speed, she lets out a long visceral yell on the “y” that is high pitched, powerful, and thoroughly punk. It’s a superb performance, yet Bag is not interviewed in this film.

Reyes’s poem draws attention to that omission as the narrator searches for a mere glimpse of “a few brown Mexican faces.” This speaks to the longing and the difficulty for Chicanas to see themselves reflected in the very same spaces that offer the possibility of belonging. Over thirty years since the film, Bag is now experiencing a surge in her career and has sparked renewed interest in histories of Chicanas in punk. She has written two books including the memoir: Violence Girl: From East L.A. Rage to L.A. Stage – A Chicana Punk Story (2011) and is sought out for speaking engagements on university campuses. Bag is able to tell her story now through writing, something a film dedicated to documenting punk music was not able to do. In retrospect, thirty-five years later, Bag’s current visibility emphasizes the further marginalization of Chicanas in punk the film produces by silencing her speaking voice against the audible power of her singing voice. Recovering Chicana histories in music may not happen through film, I propose that it is happening in the soundscapes of new Chicana literature. Importantly, new characters emerge and representations that are minor, marginalized, or non-existent in the dominant literary landscape of Aztlán are rendered legibly and audibly.

Barber of East LA-era Butchlális de Panochtítlan, (l-r) Claudia Rodriguez, Mari Garcia, Raquel Gutiérrez, Image by Hector Silva

***

Theorizing the flashback in Chicana literature raises new questions about temporality that invite and innovate ways to trace the social through aesthetics, politics, music, sound, place and memory. Is flashback 80s night at the local dance club or 80s hour on the radio always retrospective? Also, who do we envision in the sonic and cultural imaginary of “the 80s”? As a dominant population in Los Angeles and California, it is outrageous to presume that Chicanas/os or Mexican-Americans were not a significant part of alternative music scenes in Los Angeles. This post turns up the volume on the ’80s soundscapes of Chicana literature via Verónica Reyes’s poem “Torcidaness: Tortillas and Me,” to argue that one cannot nostalgically remember the 80s in a flashback radio hour or 80s night at the club and forget East L.A.

“Torcidaness” (Twistedness) speaks in an intimate voice homegirl-to-homegirl: “Tú sabes, homes how it is in—el barrio.” Through this address the narrator describes the sense of knowing herself as different and “a little off to the side on the edge” much like a hand formed tortilla. In the opening stanza, Reyes introduces the metaphor for queerness that runs through the poem in the image of the homemade corn tortilla, “crooked, lopsided and torcida.” Part of Reyes’s queer aesthetics prefers a slightly imperfect shape to her metaphorical tortillas rather than one perfectly “round and curved like a pelota.” As a tongue-in-cheek stand-in for Mexicanness, the narrator privileges the homemade quality of “torcidaness” versus a perfect uniformity to her queerness.

homemade corn tortillas, image by flikr user hnau, (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Importantly, the narrator locates her queer story that begins in childhood as “a little chamaca” in the Mexican barrios of East Los Angeles. “Torcidaness” names the cross streets to an old corner store hangout and brings East L.A. more into relief:

Back then on Sydney Drive and Floral in Belvedere District

Oscar’s store at the esquina near the alley was the place to be

We’d hang out and play: Centipede Asteroids Pac Man

or Ms. Pac Man (Oh yeah, like she really needed a man)

and even Galaga… Can you hear it? Tu, tu, tu… (very Mexican ?que no?)

Tú, tú, tú (Can you hear Eydie Gorme? Oh how so East L.A.) Tú, tú, tú…”

Coming at you … faster faster—Oh, shit. Blast! You’re dead (22).

This aurally rich stanza rings with the names of classic video games of the early 1980s. Reyes reminds us that video games are not strictly visual, they’re characterized by distinct noises, quirky blips and beeps, and catchy “chiptunes,” electronic synthesizer songs recorded on 8-bit sound chips. The speaker riffs off the playful noises in the space game Galaga, asking the reader to remember it through sound: “Can you hear it?” Capturing the shooting sounds of the game in the percussive phrase, “tú, tú, tú” prompts a bilingual homophonic listening that translates “tú” into “you.” The phrase is only a brief quote, a sample you could say, and the poem seems to argue that you’d have to be a homegirl to know where it comes from. The full verse of its source goes like this: “Me importas tú, y tú, y tú / y solamente tú / Me importas tú, y tú, y tú / y nadie mas que tú” as sung by the American singer Eydie Gorme with the Trio Los Panchos in their 1964 recording of “Piel Canela.”

To some extent the poem is not overly concerned with offering full translations, linguistic or cultural, but the reader is invited to corporeally join in the game of “Name That Tune.” The assumption is that Gorme’s Spanish language recordings of boleros with Los Panchos are important to many U.S. Mexicans and they remain meaningful across generations. And importantly, this “flashback” moment is not an anachronistic reference, rather it says something about the enduring status of boleros and the musical knowledge expected of a homegirl. Reyes’s temporal juxtaposition of the electronic sounds of the video game with the Spanish language sounds of a classic Mexican love song—and their easy, everyday coexistence in a Chicana’s soundscape–is part of what the narrator means by, “Oh how so East L.A.”

As a map, this poem locates the ’80s in part through plentiful references to the new electronic toys that became immensely popular in the US, yet Reyes does not fetishize the technology nor does she abstract Mexican experiences from these innovations as the American popular imaginary does all too often. Rather, she situates the experience of playing these new toys in a corner neighborhood store among other Mexican kids. The deft English-Spanish code switching audible in lines such as, “Oscar’s store at the esquina near the alley was the place to be,” is also part of the poem’s grammatically resistant bilingual soundscape. In these ways the poem makes claims about belonging and puts pressure on how we remember. There is danger in remembering only the game as a nostalgic collective memory and not the gamers themselves.

Galaga High Scores, image by Jenny Stoever

As a soundtrack, Reyes’s poem remembers the 80s through extensive references to the alternative rock music and androgynous and flamboyant artists of the MTV generation. This musical lineage becomes the soundtrack to the queer story in the poem. Through the music, the narrator produces a temporally complex “flashback” where queer connections, generational turf marking, and Mexicanness all come together.

No more pinball shit for us. That was 1970-something mierda

We were the generation of Atari—the beginning of digital games (22)

[. . .]

This was Siouxsie and the Banshees’ era with deep black mascara

The gothic singer who hung out with Robert Smith and Morrissey

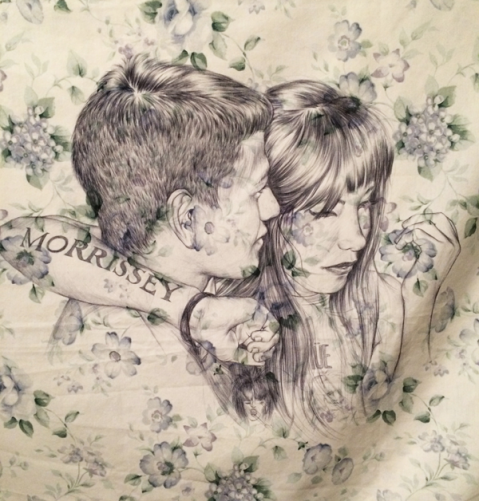

The Smiths who dominated airwaves of Mexican Impala cars (23)

In these lines the narrator shows no nostalgia for the 1970s and boasts intense pride for all things new ushered in with the new decade. She brags about a new generation defined by new cultural icons like video games and synthesizer driven music. And while this music’s sound discernibly breaks from the 70s, its alternative sensibility isn’t just about sound, it’s about a look where “deep black mascara” and dark “goth” aesthetics – for girls and boys – are all the rage and help fans find each other. Simply dropping a band’s or artist’s name like “Siouxsie” or “Morrissey” or quoting part of a song conjures entire musical genres, bringing into relief a new kind of gender ambiguity and queer visibility that flourished in the 1980s. The poem is dotted with names like Boy George, Cyndi Lauper, Wham!, Elvis Costello, X, Pretenders, all musicians one might hear now during a “flashback 80s” radio hour radio or club theme night.

Sandy and Siouxsie, 2007, Shizu Saldamando, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist. See Shizu’s work through January 8, 2018 at the Pacific Standard Time show “My Barrio: Emigdio Vasquez and Chicana/o Identity in Orange County” at Chapman University.

The complex sense of time-space of the “flashback” as a theoretical concept is part of what links seemingly discrete flashback events: club nights, radio hours, musical intertexts. What is new about the “flashback” in this context is the unexpected site (literature) and literature’s unexpected Chicana subjects who frame readers’ listenings. Reyes’s poem represents and reminds me that the reason I go to dance clubs has always been for the love of music, all music, a feeling shared passionately among my stylish and musically eclectic friends (read more in my SO! post “New Wave Saved My Life.”). The last 80s night I went to was earlier this summer at Club Elysium in Austin, Texas, with my partner Cindy and our friend Max, who says he loves it because everyone there is his age – and for the love of new wave and fashion! The DJ played requests all night which made some of the transitions unexpected. But there we were, three Chicanos, less than ten years apart in age, enjoying a soundscape any 80s kid – from SoCal or Texas — would be proud of. When I got home I added four new songs we heard and danced to that night to my oldest Spotify list titled, “Before I Forget the 80s.” Although the purpose of this list is to stretch my memory of the music as a living pulsing archive, it also recovers the memory of this great night out with friends that extends beyond the physical dance floor.

.

Spotify Playlist for “Torcidaness” by Wanda Alarcon

Yet, in “Torcidaness,” remembering this music is mediated by the Chicana lesbian storyteller’s perspective who keenly tunes into these sounds and signs of alternative music and gender from East Los Angeles. The line, “The Smiths who dominated airwaves of Mexican Impala cars,” has implications that she was not alone in these queer listenings, as Reyes casually juxtaposes the image of lowrider car culture associated with Chicano hypermasculinity with the ambiguous sexuality of the Manchester based band’s enigmatic singer, Morrissey. Morrissey and lead guitarist Johnny Marr captivated generations of music listeners with their bold guitar driven sound, infectious melodies, and neo-Wildean homoerotic lyrics in the albums The Smiths (1983), Meat is Murder (1985), and The Queen is Dead (1986).

Recalling the song, “This Charming Man” against the poem’s reference to an Impala lowrider complicates how I hear the lyric: “Why pamper life’s complexities when the leather runs smooth on the passenger seat?” In a flash(back), the gap between the UK and East L.A. is somehow bridged in this queer musical mediation echoing what Karen Tongson calls “remote intimacies across time.” Although the poem reads like a celebration, there is a critique here in lines such as these. Chicanos and people of color are never at the forefront of who is imagined to be “alternative” in histories of alternative rock music. A vexing exception can be found in the Morrissey fandom. Mozlandia, Melissa Mora Hidalgo’s study in “transcultural fandom” is partly a response to troubling misrepresentations of Chicano fans of Morrissey. In the important work of Chicana representation where audibility is as needed as visibility, this poem not only remembers but it documents queer Chicana/o presence in these alternative 80s music scenes.

“Embrace Series: Morrissey Night” by Shizu Saldamando, LA 2009, Ballpoint pen on fabric, 72 x 120 inches. Image courtesy of the artist. See Shizu’s work at the LA Japanese American National Museum’s Transpacific Borderlands show through 25 February 2018.

By poem’s end, “torcidaness,” a Spanglish term, comes to mean lesbian, working class, and Chicana of the eighties generation all at once. Tuning into the poem’s soundscape enables the possibility of hearing all of these queer meanings simultaneously as well as the possibility of hearing Aztlán, vis-a-vis Eydie Gorme, in a video game. In these ways, Verónica Reyes’s sonically rich poem renders East Los Angeles and the 1980s as an important nexus for recovering Chicana histories and Chicana lesbian representation.

Ultimately “Torcidaness and Me” captures the joy and the struggle of queer Chicana belonging in this new narrative of what Cherrie Moraga calls, “Queer Aztlán.” Reyes writes, “Yep, this was the eighties and I was learning my crookedness.” At the same time, the compatibility of the term “queer” to tell Chicana stories is challenged by the presence of alternative ways to indicate ambiguity of gender and sexuality. In this poem, “crookedness,” “torcidaness,” “my torcida days to come,” and “marimacha” all convey “queerness” in forms more audible and meaningful to a homegirl from East L.A. If there is a sound to gender—to marimachas, malfloras, jotas, butches/femmes, what does using the word “queer” do to how we hear them? Some meanings are lost in translation, yet I don’t believe that translation should always be the goal.

Theorizing the concept of the flashback in the soundscapes of this generation of Chicana authors rejects the abstract and diffuse notion of 80s themed events deployed in mainstream American culture and resists the erasure of Chicanos and Latinos in the ways we remember this important musical decade. The stakes involved in representing and remembering such histories are high. Yet Chicana histories, experiences, sexualities, subjectivities, intimacies, language, style, desires cannot be understood without a deep recognition of Chicana lesbians and butch/femme as subjects of literature and the communities we live in. As part of a decolonial feminist listening praxis, the flashback becomes an important tool linking listening with remembering as more diverse Chicana worlds emerge.

—

Featured Image: Shizu Saldamando’s Pee Chee LA 2004, courtesy of the artist. See Shizu’s work at the LA Pacific Standard Time Show Día de los Muertos: A Cultural Legacy, Past, Present & Future at Self Help Graphics opening September 17th, 2018.

—

Wanda Alarcón is a lecturer in the Department of Feminist Studies at UC Santa Cruz. She is a recipient of the Carlos E. Castañeda Postdoctoral Fellowship in the Center for Mexican American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin (2016 –2017). She received her Ph.D. in Ethnic Studies with a Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality from UC Berkeley in 2016, and earned an M.A. in English & American Literature from Binghamton University. Her research interests lie at the intersections of decolonial feminism, sound studies, popular music, eighties studies, and Chicana/o and Latinx cultural studies. Her interdisciplinary research theorizes “listening” as a decolonial feminist praxis with which to remember alternate histories of Chicana/o belonging within and out of national limits. In particular, her research argues that queer Chicana/x and Latina/x sonics become more audible in the soundscapes of Greater Mexico. At home Wanda plays piano almost every day, tinkers with bass guitar, and enjoys singing in her car. She listens to The Style Council and The Libertines in equal measure and is active on Spotify where she makes playlists for work, play, and sharing with friends.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Listening to Punk’s Spirit in its Pre-, Proto- and Post- Formations – Yetta Howard

Could I Be Chicana Without Carlos Santana?–Wanda Alarcon

If La Llorona Was a Punk Rocker: Detonguing The Off-Key Caos and Screams of Alice Bag--Marlén Rios

Share this:

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Rhetoric After Sound: Stories of Encountering “The Hum” Phenomenon

- Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions

- Wingsong: Restricting Sound Access to Spotted Owl Recordings

- Listening Together/Apart: Intimacy and Affective World-Building in Pandemic Digital Archival Sound Projects

- The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments