Unsettling the World Soundscape Project: Soundscapes of Canada and the Politics of Self-Recognition

Welcome to Unsettling the World Soundscape Project, a new series in which we critically investigate the output of early acoustic ecology and assess its continuing value for today’s sound studies. The writings and subsequent musical compositions of original WSP members like R. Murray Schafer, Barry Truax, and Hildegard Westerkamp have been the locus of much critical engagement; ubiquitous references to their work often contain tensions born from the need to acknowledge their lasting influence while critiquing the ideologies driving their work. Yet little attention has been paid to the auditory documents produced by the WSP itself as its members experimented their way through the process of developing methodologies for soundscape research. Drawing on the notion of “unsettled listening” that I wrote about here on Sounding Out! last summer, we pay particular attention to issues of cross-cultural representation in the work of the WSP and ask how their successes and failures can inform new investigations into the sonic environments of the world.

Welcome to Unsettling the World Soundscape Project, a new series in which we critically investigate the output of early acoustic ecology and assess its continuing value for today’s sound studies. The writings and subsequent musical compositions of original WSP members like R. Murray Schafer, Barry Truax, and Hildegard Westerkamp have been the locus of much critical engagement; ubiquitous references to their work often contain tensions born from the need to acknowledge their lasting influence while critiquing the ideologies driving their work. Yet little attention has been paid to the auditory documents produced by the WSP itself as its members experimented their way through the process of developing methodologies for soundscape research. Drawing on the notion of “unsettled listening” that I wrote about here on Sounding Out! last summer, we pay particular attention to issues of cross-cultural representation in the work of the WSP and ask how their successes and failures can inform new investigations into the sonic environments of the world.— Guest Editor Randolph Jordan

—

In October of 1973, two young sound recordists embarked on an ambitious field trip across Canada, traversing over 7000 kilometers to commit the national soundscape to tape. From St. John’s, Newfoundland to the harbor of Vancouver, British Columbia, Bruce Davis and Peter Huse pointed their microphones at the things they felt best exemplified their vast country.

These recordings would become the backbone for Soundscapes of Canada, a series of ten hour-long radio programs carried across the country by the national broadcaster, the CBC. Conceived and produced by the World Soundscape Project (WSP)—a research group formed at Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University in the late 1960s and helmed by the composer and sound theorist, R. Murray Schafer—in its entirety Soundscapes of Canada was an impressively sprawling, eclectic document. Comprised of guided listening exercises and avant-garde sound collages, the program’s stated goal was to open the ears of Canadian listeners to the importance of sonic experience, and to alert them to what they warned was the degradation of the soundscape thanks to the mounting din of industrial modernity.

But there was much more happening out of earshot. Created at a time when Canada’s cultural identity was rapidly changing thanks to an unprecedented swell in immigration from non-European countries, the WSP’s portrait of the nation all but ignored its First Nations and its “visible minorities,” as they would come to be known. While the series was an important statement in the WSP’s larger efforts to bring sound to the forefront of cultural conversation, it is arguably more important to listen to Soundscapes of Canada for what it leaves out, for voices silent and silenced.

For Schafer, the industrialized world had grown measurably louder and qualitatively noisier, which troubled him for both environmental and social reasons. In his 1977 book, The Tuning of the World, Schafer would write, “For some time, I have…believed that the general acoustic environment of a society can be read as an indicator of social conditions which produce it and may tell us much about the trending and evolution of that society” (7). Given the worryingly poor state of the soundscape, for Schafer it followed that society was in bad shape. He was wistful for quieter times, for the days of Goethe, when the cry of the half-blind night watchman of Weimer was within earshot of every one of the town’s inhabitants. Unstated, but implied, here, was the notion that as communities expanded beyond every member’s ability to hear a familiar sound, their common identity would necessarily be eroded. And for Schafer, this was precisely what was happening to Canada.

The WSP’s discussion of “soundmarks” in parts three and four of the series was perhaps their most powerful statement about the stakes for preserving and promoting the nation’s sonic heritage. A “soundmark” is, in the WSP’s lexicon of neologisms, roughly analogous to a landmark: it’s a sound that is supposedly instantly recognizable to members of a community, an irreplaceable acoustic feature of a particular place. In the conclusion to program three, “Signals, Soundmarks and Keynotes,” Schafer intoned, “It takes time for a sound to take on rich, symbolic character—a lifetime perhaps, or even centuries. This is why soundmarks should not be tampered with carelessly. Change the soundmarks of a culture and you erase its history and mythology. Myths take many forms. Sounds have a mythology too. Without a mythology, a culture dies.”

So it seems fair to ask: exactly whose mythology stood to be snuffed out? For Schafer, Canadian culture was (or ought to be) synechdochal with the land, with the nation’s vast, largely uninhabited expanses that stretched all the way to the North Pole. Canadians were (or ought to be) a rugged, self-reliant people—stoic pioneers who shunned cosmopolitan (read ethnic) urban centers, opting for a quiet life in harmony with the country’s settler heritage. This was certainly reflected in program four, “Soundmarks of Canada.” Over the course of an hour CBC listeners would have heard an austere montage almost entirely comprised of mechanical alarms (foghorns and air sirens) and church bells. Each sound presented, carefully, discreetly as though displayed in a museum, free from any traffic noise or sidewalk bustle that might distract the listener. Anyone unfamiliar with the Canadian soundscape would be forgiven for coming to the conclusion that the world’s second largest nation was a bastion of early industrial machinery, a sanctuary for quiet, self-reliant, God-fearing folk.

“Soundmarks of Canada” not only omitted the soundmarks of Canadian cities, it also excluded any sonic trace of the country’s vibrant ethnic and First Nations communities. Produced in the years following the passage of the 1971 Multiculturalism Policy of Canada—which had been adopted in response to a boom of immigration from non-European nations—their portrait of a pastoral, post-colonial British outpost shunted the country’s sizeable non-Christian, ethnic population squarely out of earshot. It should also go without saying that the soundmarks they so prized were deeply entangled with a silencing of Canada’s indigenous population; of a protracted, often violent and brutal, campaign of assimilation that replaced one set of sonic practices with another. For generations of Indigenous Canadians, the sounds of church bells would likely not have connoted community or belonging, but would have rather reverberated with echoes of the “reeducation” in settler religion and language that many were forced to endure in Canada’s residential schools—church-run institutions to which countless children were spirited away against their parents and communities’ wishes.

This is not to say that any of this was intentional, that the WSP deliberately plugged their ears to Canada’s marginal communities, or that they intended to slight these groups in any way. It may be more accurate to ascribe ignorance and omission to the project, structural forms of inequality that dog even the most well meaning white settlers. Regardless of intent, however, the result is the same.

Soundscapes of Canada shows a troubling politics of self-recognition in action that is far too common throughout the nation’s history. By disproportionately representing the voices and sounds of European Canadians the series necessarily supported the idea that they were, if not the only ones, then at least “ordinary” and incumbent. Projects like these promote and condition a sense of unity and similarity that constitute the nation’s imagination of itself. Benedict Anderson famously observed that nations come into being and are maintained through the cultural work that leads its citizens to identify with the state. Institutions and practices from censuses, maps, nationally available print journalism, etc. all allow people in far-off locales to imagine themselves constituting a limited and sovereign community. In his classic book, Imagined Communities, Anderson proposes that nations have also historically been conceived, created, and ratified through sound. Writing specifically of national anthems, Anderson coins the term “unisonance” to describe the power that sound can have to seemingly erode the boundaries between self and other: “How selfless this unisonance feels! If we are aware that others are singing these songs precisely when and as we are, we have no idea who they may be, or even where, out of earshot, they are singing. Nothing connects us all but imagined sound” (149).

It is significant that the WSP chose the radio—the CBC in particular—as the vehicle for their ambitious project. In the mid-1970s, not only did radio offer the widest reach of any sonic medium, but it also had a particular cultural resonance for Canadians. A nation as vast and varied as Canada could have only come about thanks to mediation; its vastness has always required means of traversing or shrinking space to secure its borders, both psychic and geographical. The westward expansion of the post-indigenous nation was accomplished first by canoe, then by rail, and, beginning in the 1920s, by radio. Appropriately, it was the Canadian National Railway (CNR) that produced the first transnational radio broadcast in 1927—the national anthem performed by bells on the carillon of the Peace Tower—broadcasting the event to railway passengers and home listeners alike. Since the middle part of the 20th century, the national broadcaster has been understood as something of a bulwark against encroaching American culture.

The history of the Canadian airwaves is profoundly mired in struggles to promote, produce, and foster content that might keep the national identity from being completely subsumed under the sprawl and heft of the American culture industry. Schafer had mixed feelings about the medium. On the one hand, he was skeptical of his one-time teacher and mentor, Marshall McLuhan’s, analysis that radio, by its very nature, enfolded listeners in a shared acoustic space, effectively “retribalizing” society. Schafer felt that the airwaves had been packed to such a dense and frenetic level that they actually created “sound walls” that effectively isolated listeners in their own solipsistic, acoustic bubbles. But there was hope for the radio in that it could also facilitate a return to a more wholesome and connected state of being and of listening. Schafer noted this duality in his essay “Radical Radio,” writing, “If modern radio overstimulates, natural rhythms could help put mental and physical well-being back in our blood. Radio may, in fact, be the best medium for accomplishing this” (209). Sonic technology was a source of ambivalence for Schafer; he coined the term “schizophonia” to describe the separation of sound from source that recording effected. He believed that it was problematic to populate the world with copies he deemed inherently inferior to the “original” sonic event. Given the opportunity to reach such a wide swath of the Canadian public, Schafer swallowed his distaste for the schizophonic medium and offered a sonic missive on how to compose a healthy and prosperous nation.

Forty years on, Soundscapes of Canada still stands as a unique experiment in imagining how to build and maintain a nation through sound. But in the same regard it also serves as a troubling reminder of how sonic media can work to occlude the voices of marginal citizens, thereby preventing them from fully finding the place in the national soundscape, simply by ignoring their soundmarks and aural practices. If a nation needs a myth, it can do better than telling stories about the necessity of shoring up a colonial legacy whose time has come.

Readers interested in listening to the full series can stream all ten episodes through the website of the Canadian Music Centre.

—

Mitchell Akiyama is a Toronto-based scholar, composer, and artist. His eclectic body of work includes writings about plants, animals, cities, and sound art; scores for film and dance; and objects and installations that trouble received ideas about perception and sensory experience. Akiyama recently completed his Ph.D. in communications at McGill University. His doctoral work offers a critical history of sound recording in the field and examines an eclectic range of subjects, from ethnographers recording folksongs in southern American penal work camps to biologists trying determine whether or not animals have language to the political valences of sound art practices.

—

Featured image: “Toronto” by Flickr user Kristel Jax. All other images via the author.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

À qui la rue?: On Mégaphone and Motreal’s Noisy Public Sphere — Lilian Radovac

Sounding Out! Podcast Episode #7: Celebrate World Listening Day with the World Listening Project — Liana M. Silva

Within a Grain of Sand: Our Sonic Environment and Some of Its Shapers — Maile Colbert

The Eldritch Voice: H. P. Lovecraft’s Weird Phonography

Welcome to the last installment of Sonic Shadows, Sounding Out!’s limited series pursuing the question of what it means to have a voice. In the most recent post, Dominic Pettman encountered several traumatized birds who acoustically and uncannily mirror the human, a feedback loop that composes what he called “the creaturely voice.” This week, James Steintrager investigates the strange meaning of a “metallic” voice in the stories of H.P. Lovecraft, showing how early sound recording technology exposed an alien potential lingering within the human voice. This alien voice – between human and machine – was fodder for techniques of defamiliarizing the world of the reader.

Welcome to the last installment of Sonic Shadows, Sounding Out!’s limited series pursuing the question of what it means to have a voice. In the most recent post, Dominic Pettman encountered several traumatized birds who acoustically and uncannily mirror the human, a feedback loop that composes what he called “the creaturely voice.” This week, James Steintrager investigates the strange meaning of a “metallic” voice in the stories of H.P. Lovecraft, showing how early sound recording technology exposed an alien potential lingering within the human voice. This alien voice – between human and machine – was fodder for techniques of defamiliarizing the world of the reader.— Guest Editor Julie Beth Napolin

—

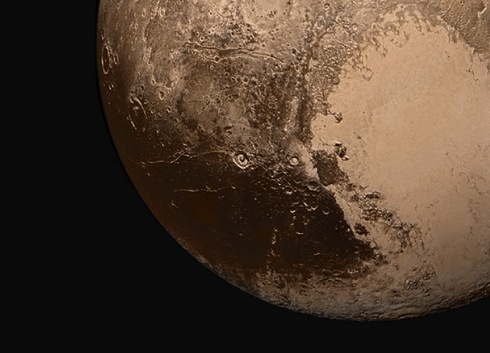

A decade after finding itself downsized to a dwarf planet, Pluto has managed to spark wonder in the summer of 2015 as pictures of its remarkable surface features and those of its moon are delivered to us by NASA’s New Horizons space probe. As scientists begin to tentatively name these features, they have drawn from speculative fiction for what they see on the moon Charon, giving craters names including Spock, Sulu, Uhuru, and—mixing franchises—Skywalker . From Doctor Who there will be a Tardis Chasma and a Gallifrey Macula. Pluto’s features stretch back a bit further, where there will also be a Cthulhu Regio, named after the unspeakable interstellar monster-cum-god invented by H. P. Lovecraft.

We can imagine that Lovecraft would have been thrilled, since back when Pluto was first discovered in early 1930 and was the evocative edge of the solar system, he had turned the planet into the putative home of secretive alien visitors to Earth in his short story “The Whisperer in Darkness.” First published in the pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1931, “The Whisperer in Darkness” features various media of communication—telegraphs, telephones, photographs, and newspapers—as well as the possibilities of their manipulation and misconstruing. The phonograph, however, plays the starring role in this tale about gathering and interpreting the eerie and otherworldly—the eldritch, in a word—signs of possible alien presence in backwoods Vermont.

In the story, Akeley, a farmer with a degree of erudition and curiosity, captures something strange on a record. This something, when played back by the protagonist Wilmarth, a folklorist at Lovecraft’s fictional Miskatonic University, goes like this:

Iä! Shub-Niggurath! The Black Goat of the Woods with a Thousand Young! (219)

The sinister resonance of a racial epithet in what appears to be a foreign or truly alien tongue notwithstanding, this story features none of the more obvious and problematic invocations of race and ethnicity—the primitive rituals in the swamps of Louisiana of “The Call of Cthulhu” or the anti-Catholic immigrant panic of “The Horror at Red Hook”—for which Lovecraft has achieved a degree of infamy. Moreover, the understandable concern with Lovecraft’s social Darwinism and bad biology in some ways tends to miss how for the author—and for us as well—power and otherness are bound up with technology.

The transcription of these exclamations, recorded on a “blasphemous waxen cylinder,” is prefaced with an emphatic remark about their sonic character: “A BUZZING IMITATION OF HUMAN SPEECH” (219-220). The captured voice is further described as an “accursed buzzing which had no likeness to humanity despite the human words which it uttered in good English grammar and a scholarly accent” (218). It is glossed yet again as a “fiendish buzzing… like the drone of some loathsome, gigantic insect ponderously shaped into the articulate speech of an alien species” (220). If such a creature tried to utter our tongue and to do so in our manner—both of which would be alien to it—surely we might expect an indication of the difference in vocal apparatuses: a revelatory buzzing. Lovecraft’s story figures this “eldritch sound” as it is transduced through the corporeal: as the timbral indication of something off when the human voice is embodied in a fundamentally different sort of being. It is the sound that happens when a fungoid creature from Yuggoth—the supposedly native term for Pluto—speaks our tongue with its insectile mouthparts.

The transcription of these exclamations, recorded on a “blasphemous waxen cylinder,” is prefaced with an emphatic remark about their sonic character: “A BUZZING IMITATION OF HUMAN SPEECH” (219-220). The captured voice is further described as an “accursed buzzing which had no likeness to humanity despite the human words which it uttered in good English grammar and a scholarly accent” (218). It is glossed yet again as a “fiendish buzzing… like the drone of some loathsome, gigantic insect ponderously shaped into the articulate speech of an alien species” (220). If such a creature tried to utter our tongue and to do so in our manner—both of which would be alien to it—surely we might expect an indication of the difference in vocal apparatuses: a revelatory buzzing. Lovecraft’s story figures this “eldritch sound” as it is transduced through the corporeal: as the timbral indication of something off when the human voice is embodied in a fundamentally different sort of being. It is the sound that happens when a fungoid creature from Yuggoth—the supposedly native term for Pluto—speaks our tongue with its insectile mouthparts.

Yet, reading historically, we might understand this transduction as the sound of technical mediation itself: the brazen buzz of phonography, overlaying and, in a sense, inhabiting the human voice.

For listeners to early phonographic recordings, metallic sounds—inevitable given the materials used for styluses, tone arms, diaphragms, amplifying horns—were simply part of the experience. Far from capturing “the unimaginable real” or registering “acoustic events as such,” as media theorist Friedrich Kittler once put the case about Edison’s invention, which debuted in 1877, phonography was not only technically incapable of recording anything like an ambient soundscape but also drew attention to the very noise of itself (23).

For the first several decades of the medium’s existence, patent registers and admen’s pitches show that clean capture and reproduction were elusive rather than given. An account in the Literary Digest Advertiser of Valdemar Poulsen’s Telegraphone, explains the problem:

The talking-machine records sound by the action of a steel point upon some yielding substance like wax, and reproduces it by practically reversing the operation. The making of the record itself is accompanied by a necessary but disagreeably mechanical noise—that dominating drone—that ‘b-r-r-r-r’ that is never in the human voice, and always in its mechanical imitations. One hears metallic sounds from a brazen throat—uncanny and inhuman. The brittle cylinder drops on the floor, breaks—and the neighbors rejoice!

The talking-machine records sound by the action of a steel point upon some yielding substance like wax, and reproduces it by practically reversing the operation. The making of the record itself is accompanied by a necessary but disagreeably mechanical noise—that dominating drone—that ‘b-r-r-r-r’ that is never in the human voice, and always in its mechanical imitations. One hears metallic sounds from a brazen throat—uncanny and inhuman. The brittle cylinder drops on the floor, breaks—and the neighbors rejoice!

The Telegraphone, which recorded sounds “upon imperishable steel through the intangible but potent force of electromagnetism” such that no “foreign or mechanical noise is heard or is possible,” of course promised to make the neighbors happy not by breaking the cylinder but rather by taking the inhuman ‘b-r-r-r-r’ out of the phonographically reproduced voice. Nonetheless, etching sound on steel, the Telegraphone was still a metal machine and unlikely to overcome the buzz entirely.

In his account of “weird stories” and why the genre suited him best, Lovecraft explained that one of his “strongest and most persistent wishes” was “to achieve, momentarily, the illusion of some strange suspension or violation of the galling limitations of time, space, and natural law which forever imprison us and frustrate our curiosity about the infinite cosmic spaces beyond the radius of our sight and analysis.” In “The Whisperer in Darkness,” Lovecraft put to work a technology that was rapidly becoming commonplace to introduce a buzz into the fabric of the everyday. This is the eldritch effect of Lovecraft’s evocation of phonography. While we might wonder whether a photograph has been tampered with, who really sent a telegram, or with whom we are actually speaking over a telephone line—all examples from Lovecraft’s tale—the central, repeated conundrums for the scholar Wilmarth remain not only whose voice is captured on the recorded cylinder but also why it sounds that way.

The phonograph transforms the human voice, engineers a cosmic transduction, suggesting that within our quotidian reality something strange might lurk. This juxtaposition and interplay of the increasingly ordinary and the eldritch is also glimpsed in an account of Charles Parson’s invention the Auxetophone, which used a column of pressurized air rather than the usual metallic diaphragm. Here is an account of the voice of the Auxetophone from the “Matters Musical” column of The Bystander Magazine from 1905: “Long ago reconciled to the weird workings of the phonograph, we had come to regard as inevitable the metallic nature of its inhuman voice.” The new invention might well upset our listening habits, for Mr. Parson’s invention “bids fair to modify, if not entirely to remove,” the phonograph’s “somewhat unpleasant timbre.”

The phonograph transforms the human voice, engineers a cosmic transduction, suggesting that within our quotidian reality something strange might lurk. This juxtaposition and interplay of the increasingly ordinary and the eldritch is also glimpsed in an account of Charles Parson’s invention the Auxetophone, which used a column of pressurized air rather than the usual metallic diaphragm. Here is an account of the voice of the Auxetophone from the “Matters Musical” column of The Bystander Magazine from 1905: “Long ago reconciled to the weird workings of the phonograph, we had come to regard as inevitable the metallic nature of its inhuman voice.” The new invention might well upset our listening habits, for Mr. Parson’s invention “bids fair to modify, if not entirely to remove,” the phonograph’s “somewhat unpleasant timbre.”

What the phonograph does as a medium is to make weird. And what making weird means is that instead of merely reproducing the human voice—let alone rendering acoustic events as such—it transforms the latter into its own: an uncanny approximation, which fails to simulate perfectly with regard to timbre in particular. Phonography reveals that the materials of reproduction are not vocal chords, breath, labial and dental friction—not flesh and spirit, but vibrating metal.

Although we can only speculate in this regard, I would suggest that “The Whisperer in Darkness” was weirder for readers for whom phonographs still spoke with metallic timbre. The rasping whisper of the needle on cylinder created what the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky was formulating at almost exactly the same time as the function of the literary tout court: defamiliarization or, better, estrangement. Nonetheless, leading the reader to infer an alien presence behind this voice was equally necessary for the effect. After all, if we are to take the Auxetophone as our example—an apparatus announced in 1905, a quarter of a decade before Lovecraft composed his tale, and that joined a marketplace burgeoning with metallic-voice reducing cabinets, styluses, dampers, and other devices—phonographic listeners had long since become habituated to the inhumanity of the medium. That inhumanity had to be recalled and reactivated in the context of Lovecraft’s story.

To understand fully the nature of this reactivation, moreover, we need to know precisely what Lovecraft’s evocative phonograph was. When Akeley takes his phonograph into the woods, he adds that he brought “a dictaphone attachment and a wax blank” (209). Further, to play back the recording, Wilmarth must borrow the “commercial machine” from the college administration (217). The device most consistent with Lovecraft’s descriptions and terms is not a record player, as we might imagine, but Columbia Gramophone Company’s Dictaphone. By the time of the story’s setting, Edison Phonograph’s had long since switched to more durable celluloid cylinders (Blue Amberol Records; 1912-1929) in an effort to stave off competition from flat records. Only Dictaphones, aimed at businessmen rather than leisure listeners, still used wax cylinders, since recordings could be scraped off and the cylinder reused. The vinyl Dictabelt, which eventually replaced them, would not arrive until 1947.

To understand fully the nature of this reactivation, moreover, we need to know precisely what Lovecraft’s evocative phonograph was. When Akeley takes his phonograph into the woods, he adds that he brought “a dictaphone attachment and a wax blank” (209). Further, to play back the recording, Wilmarth must borrow the “commercial machine” from the college administration (217). The device most consistent with Lovecraft’s descriptions and terms is not a record player, as we might imagine, but Columbia Gramophone Company’s Dictaphone. By the time of the story’s setting, Edison Phonograph’s had long since switched to more durable celluloid cylinders (Blue Amberol Records; 1912-1929) in an effort to stave off competition from flat records. Only Dictaphones, aimed at businessmen rather than leisure listeners, still used wax cylinders, since recordings could be scraped off and the cylinder reused. The vinyl Dictabelt, which eventually replaced them, would not arrive until 1947.

Meanwhile, precisely when the events depicted in “The Whisperer in Darkness” are supposed to have taken place, phonography was experiencing a revolutionary transformation: electronic sound technologies developed by radio engineers were hybridizing the acoustic machines, and electro-acoustic phonographs were in fact becoming less metallic in tone. Yet circa 1930, as the buzz slipped toward silence, phonography was still the best means of figuring the sonic uncanny valley. It was a sort of return of the technologically repressed: a reminder of the original eeriness of sound reproduction—recalled from childhood or perhaps parental folklore—at the very moment that new technologies promised to hide such inhumanity from sensory perception. Crucially, in Lovecraft’s tale, estrangement is not merely a literary effect. Rather, the eldritch is what happens when the printed word at a given moment of technological history calls up and calls upon other media of communication, phonography not the least.

I have remarked the apparent absence of race as a concern in “The Whisperer in Darkness,” but something along the lines of class is subtly but insistently at work in the tale. The academic Wilmarth and his erudite interlocutor Akeley are set in contrast with the benighted, uncomprehending agrarians of rural Vermont. Both men also display a horrified fascination with the alien technology that will allow human brains to be fitted into hearing, seeing, and speaking machines for transportation to Yuggoth. These machines are compared to phonographs: cylinders for storing brains much like those for storing the human voice. In this regard, the fungoid creatures resemble not so much bourgeois users or consumers of technology as scientists and engineers. Moreover, they do so just as a discourse of technocracy—rule by a technologically savvy elite—was being articulated in the United States. Here we might see the discovery of Pluto as a pretext for exploring anxieties closer to home: how new technologies were redistributing power, how their improvement—the fading of the telltale buzz—was making it more difficult to determine where humanity stopped and technology began, and whether acquiescence in this changes was laudable or resistance feasible. As usual with Lovecraft, these topics are handled with disconcerting ambivalence.

—

James A. Steintrager is a professor of English, Comparative Literature, and European Languages and Studies at the University of California, Irvine. He writes on a variety of topics, including libertinism, world cinema, and auditory cultures. His translation of and introduction to Michel Chion’s Sound: An Acoulogical Treatise will be published by Duke University Press in fall of 2015.

—

Featured image: Taken from “Global Mosaic of Pluto in True Color” in NASA’s New Horizons Image Gallery, public domain. All other images courtesy of the author.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sound and Sanity: Rallying Against “The Voice” — Mark Brantner

DIANE… The Personal Voice Recorder in Twin Peaks — Tom McEnaney

Reproducing Traces of War: Listening to Gas Shell Bombardment, 1918 — Brían Hanrahan

Recent Comments