Sonic Connections: Listening for Indigenous Landscapes in Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles

In April 2015, ten American Indian extras walked off the set of Adam Sandler’s new film The Ridiculous Six, a spoof on the classic Magnificent Seven (1960), in protest over the gross misrepresentation of Native cultures in general, and in particular over its insults to women and elders. Allison Young, a Navajo actress who participated in walking off, stated, “Nothing has changed. We are still just Hollywood Indians.” Young is referencing a long history of the film industries’ construction of stereotypical American Indians by non-natives created to entertain non-natives.

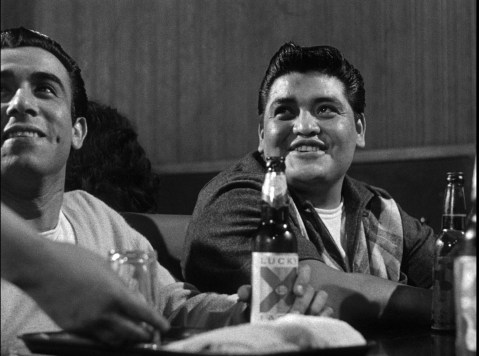

Still from the movie. From http://www.arthousecowboy.com

Within this long history exists a rare film, Kent Mackenzie’s 1961 The Exiles, re-restored and re-released in 2008 by Milestone Films. The Exiles is one of the few 20th century films that feature urban American Indians; it follows three main Native narrators from dusk to dawn as they experience the joys and struggles of urban life. Without an official score, this black and white docudrama places sound against haunting 35 millimeter black-and-white images of a downtown Los Angeles landscape. This mis-en-scène creates what Mackenzie (the white screenwriter, director and producer) asserts is “the authentic account of 12 hours.” The voiceovers of Homer Nish, a Hualipai from Valentine, Arizona who recently moved to Los Angeles after fighting in the Korean War; Yvonne Walker, originally from the White River Apache reservation in San Carlos, Arizona who first moved to the city to work as a domestic; and Tommy Reynolds, who is identified only as Mexican-Indian and is portrayed as a comedic playboy and the life of the party; narrate the intimate, day-to-day lives of urban American Indians.

From the website http://www.exilesfilm.com/

In this post, I consider what we can hear if we pay close attention to how the director incorporates the narrators in a kind of Indigenous soundscape. Mackenzie’s soundscape bring together voices as well as music. The collage of sounds traces the journeys of American Indians to and from Los Angeles in the mid-twentieth century. The sonic connections in The Exiles provide a cacophony of histories of forced movement, transit, and re-making spaces as Indigenous at the same time that it perpetuates important historical silences. I borrow Chickasaw scholar Jodi A. Byrd’s term from The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (2011), cacophony—or “discordant and competing representations” and experiences— and apply it to the sounds that inform the indigenous space represented through the film.

The narrators are part of a large population of American Indians who moved from rural reservations to urban centers after WWII. Due to the federal government’s mismanagement of Native tribes’ land and resources, and the genocidal abandonment of treaties made with tribes, the late 1950s and 1960s were times of dire economic and social conditions on reservations. The influx of Native Americans to cities also came because of assimilation campaigns in boarding schools, military service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ “Termination Era” policies (1940s –1960s) that intended to terminate the state’s bureaucratic relationships with Native tribes. Relocating Native populations from reservations into cities where work was available year-round was a key aspect of the Termination Era policies. According to Norman Klein (The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory), areas near downtown Los Angeles, including Bunker Hill where the film is primarily shot, were multi-racial neighborhoods in economic decline and therefore became relocation sites for American Indians. Importantly, both Klein and Mackenzie are silent about the prior forced removal of Tongva on that very same location that began in the 1840s.

The audio track of The Exiles contradicts the stereotypical American Indian sounds featured in Hollywood movies. The film’s contemporary mainstream Hollywood releases included sounds such as the whooping sounds of “hostile Indians” in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), the broken English spoken by the “Apache” in Delmer Daves’ Broken Arrow (1950), and stereotypes played out in John Sturges’ Magnificent Seven (1960). In the soft Southwestern Native lilt of Yvonne’s voice, the way that Homer and others add “you know?” to the end of almost every sentence they utter, alongside the rhythm of the casual banter and tenor of the men’s laughter, I hear a potential sonic archive of American Indians that talks back. For example, in a short clip when Tommy and his friends enter Café Ritz, an Indian bar, Thomas calls out over the loud rock and roll music as he passes people at the bar. Tommy shifts easily between English (“What’s happening there, man?”), Spanish (“Gracias amigo, ¿cómo estas?”), and Dine (“Yá’át’ééh. E la na tte?”). Careful attention to the cinematic soundscape provides access to voices of discontent and resiliency, practices of building and maintaining multilingual multi-tribal Indian spaces, and the flow of American Indians between reservations and multiple cities.

Understanding the sounds and the silences of The Exiles as a cacophony offers a way to appreciate how the film both perpetuates stereotypes but also provides insights into the urban American Indian experience. Mackenzie’s construction of Homer Nish and American Indian men continues a myth that it is individualized behavior that keeps Indians from the American Dream. (In his 1964 masters thesis, “A Description and Examination of the Production of The Exiles: A Film of the Actual Lives of a Group of Young American Indians” Mackenzie states outright that he believes they are responsible for the mess they created). The Exiles portrays American Indian men reading comic books, listening to rock and roll, hanging out at bars instead of working, and taking rent money away from their suffering women and children to gamble. These formulaic images of Native Americans are informed by a long history of visual, literary and legal representations of American Indians that compose Indian men as either savage, infantile and emasculated. But if we listen to the banter and laughter in the bar scenes and at home, we also hear the caring intimacy of camaradrie. The cacophony of sound provides a counterbalance to the visual representations.

The Voiceover and Realism

Mackenzie uses dialogue to direct the visual and sonic narrative of the docudrama’s soundscape. Ironically, this collaborative low budget project that stretched on for three and a half years has minimal original dialogue. They could not afford sound techs on site, so the most obvious sonic evocation of realism Mackenzie explores is asynchronous sound performed in a studio months later. In Mackenzie’s master’s thesis he writes that, to construct dialogues (they often voiced their lines with a group of people around), “people would joke around a lot” while “everybody was drinking beer” (76). The filmmaker did not find that dialogue on larger budget feature films at the time were “lifelike” and believable. He writes that people

seldom spoke of important matters directly; they seldom spoke clearly or coherently when they did speak and their everyday language was full of overlaps interruption and communications through looks, gestures and shrugs. Many sentences made the end understood. …What a person said seemed less important than how he said it. (73)

Here, it becomes clear that the “realism” Mackenzie pursues is more about a style of filmmaking rather than about an authentic rendering of Native American everyday life. If he found the actors performing lines too dramatically Mackenzie states he “would blow the scene apart by asking for more casual and apparently pointless lines” (73). He created a specially mediated recording of the people, downtown Los Angeles and the time period. In other words, he pursued realism: he did not seek to fully capture real experiences.

Tommy Reynolds and Homer Nish in Kent Mackenzie’s THE EXILES (1961).

Through interviews he guides the actors to talk about their everyday lives, their problems and their thoughts about life. Mackenzie used “improvised tracks” out of individual interviews in an attempt “to help preserve their point of view in the film.” He interviewed Homer, Tommy and Yvonne for several hours apiece, questioning and re-questioning them – not necessarily to document the subjects’ truths but “for emotional quality and general attitudes and feelings” (78). Despite his intentions, the voiceovers provide some context of the trials of everyday life and how the leads negotiated their belonging in a space far from home. Mackenzie’s realism builds a collage of soundscapes—voiceovers, background noise, music—to orchestrate a scene rather than simply document part of a 12-hour period of life.

Rock and Roll and Urban Indian Sounds

Mainstream “Hollywood Indians” are associated with a limited soundscape of drums and whoops, but Mackenzie’s use of contemporary rock and roll illustrates the complexity of the indigenous soundscape. Even though the film opens with the slow repetitive beating of the buckskin drums and a contextual opening monologue, after the drums stop it is the early surf music of Anthony Hilder and his five-piece band, The Revels, that drive many of the scenes. The music renders audible the many ways people tried to belong in new locations and within new cultures, juxtaposing the fast blast of the trumpet and guitar riffs of the Revels with the steady beat of the drum and shake of a turtle rattle.

Mackenzie continues this juxtaposition later in the film. Homer, alone on the street in front of a liquor store, opens a letter a bartender handed to him earlier in the evening. At the top of the letter is written “Peach Springs, Arizona” and tucked within the letter is a picture of an older man and woman. The camera focuses on the picture that dissolves and reemerges as a rural desert scene. The man from the picture sits beneath a tree with a girl and the woman, and rhythmically chants and shakes a rattle. There is no voice-over or dialogue; ceremonial singer Jacinto Valenzuela’s repeats a song multiple times without an English translation. The steady rattle of the dry seeds in the gourd are a sharp contrast to the pace of the Revels’ songs that saturates Homer’s earlier scenes.

Without guidance from a narrator, the scene is left to audience interpretation. The scene and its sounds could represent Homer’s sense of being displaced between times, or a homesick romanticized remembrance of family life: the moment quickly dissipates and Homer once again stands alone on a corner bathed in the streetlight. However, the music here could be a sonic connection that provides an alternative geography of indigenous space and place. Mackenzie’s collage of sound echoes the circuitous path of indigenous bodies and ideas of indigenous life in diasporas described in Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska scholar Renya Ramirez’s work in Native Hubs: Culture, Community, and Belonging in Silicon Valley and Beyond. The rattle and drum can instead signal a belonging to a community and people in a present that Homer carries within him. Through sound, Mackenzie connects Homer with his communities, traditions, and a sense of belonging regardless of spatial distance.

Mackenzie deepens this connection when he imbeds Homer in a place and community through the dancing and drumming on Hill X in the penultimate scene of the film sounds. When Homer talks about Hill X (formerly Chavez Ravine, then a site of the forced displacement of Mexican residents in Los Angeles in 1950-1952, now the site of Dodger Stadium) we hear his strategy for his own and his tribe’s collective survival. The shaking of the gourd in the desert and the dancing, singing and drumming of the 49 —lead by Mescalero singers Eddie Sunrise Gallerito and his twin cousins Frankie Red Elk and Chris Surefoot—shows a reclaiming of Los Angeles as indigenous land. Thus practices of sound and movement function as what Tonawanda Seneca scholar Mishuanna Goeman identifies as “remapping” of Indian space. Taken together with the beat of the drum, the bells and rock and roll compose the content of a Los Angeles indigenous soundscape.

The Exiles registers contemporary American Indians in motion. Homer and his comrades reclaim Hill X as Indian land with song and dance over a century after the City of Los Angeles displaced the Tongva out of that same location. At the time of the filming, American Indians were also forced to move within Los Angeles- their homes on Bunker Hill soon demolished and replaced by high rises. Paying attention and critically re-listening to the sounds of The Exiles offers an alternative soundscape of Indigenous life.

The Exiles registers contemporary American Indians in motion. Homer and his comrades reclaim Hill X as Indian land with song and dance over a century after the City of Los Angeles displaced the Tongva out of that same location. At the time of the filming, American Indians were also forced to move within Los Angeles- their homes on Bunker Hill soon demolished and replaced by high rises. Paying attention and critically re-listening to the sounds of The Exiles offers an alternative soundscape of Indigenous life.

−

Featured image: “chavez ravine” by Flickr user Paul Narvaez, CC BY-NC 2.0

−

Laura Sachiko Fugikawa holds a doctoral degree in American Studies and Ethnicity with a certificate in Gender Studies from the University of Southern California. Currently she is working on her book, Displacements: The Cultural Politics of Relocation, and teaches Asian American Studies at Northwestern University.

−

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #40: Linguicide, Indigenous Community and the Search for Lost Sounds–Marcella Ernst

The “Tribal Drum” of Radio: Gathering Together the Archive of American Indian Radio–Josh Garrett Davis

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies–Christine Ehrick

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Recent Comments