“Welles,” Belles, and Fred Allen’s Sonic Pranks: Making a Radio Auteur Laugh at Himself

Welcome back to From Mercury to Mars, our series of posts (in conjunction with Antenna) that reflect on Orson Welles’s radio career, and the upcoming anniversary of its highlight, “The War of the Worlds.”

Welcome back to From Mercury to Mars, our series of posts (in conjunction with Antenna) that reflect on Orson Welles’s radio career, and the upcoming anniversary of its highlight, “The War of the Worlds.”

When scholars discuss the effect of that play on people, they often fall into reveries about its most serious dimensions — what the Martian Panic says about human susceptibility, about the power of the media, about sound and the unknown. But it’s important to realize that, besides being terribly humorless, this approach also isn’t historically just. Although Welles was — like some of his listeners — spooked the night of the event, in the days that followed he and many others came to recognize some humor in the the whole thing, too. Later in life, Welles focused on that dimension of his memory, repeatedly recalling with laughter that when the actor John Barrymore (something of a “grand old man” of the American stage in 1938), heard the Martian invasion broadcast he tearfully decided to free his beloved dogs, so they could taste freedom before meeting the inexorable doom.

Such tall tales aren’t trivial. Actually, we misunderstand the WOTW escapade if we don’t recognize that immediately adjacent to modern America’s propensity for panic stood its equally fascinating capacity to laugh at itself. Both tendencies do cultural work, often in concert with one another. With that in mind, this week our Mercury to Mars series moves from the macabre (see Debra Rae Cohen’s piece on Welles and Dracula) to the ridiculous, focusing on the relationship between Welles’s puffed-up fame and how it was lampooned by Fred Allen, one of the great absurdist comics in modern entertainment, and perhaps the most creative radio comedian of his era.

Such tall tales aren’t trivial. Actually, we misunderstand the WOTW escapade if we don’t recognize that immediately adjacent to modern America’s propensity for panic stood its equally fascinating capacity to laugh at itself. Both tendencies do cultural work, often in concert with one another. With that in mind, this week our Mercury to Mars series moves from the macabre (see Debra Rae Cohen’s piece on Welles and Dracula) to the ridiculous, focusing on the relationship between Welles’s puffed-up fame and how it was lampooned by Fred Allen, one of the great absurdist comics in modern entertainment, and perhaps the most creative radio comedian of his era.

To introduce this crucial entertainer and to explain why his relationship to Welles matters so much, we are lucky to have one of the most important voices in radio studies today: Kathleen Battles, Associate Professor of Communication at Oakland University, author of a paradigm-shifting study of the relationship between radio and policing, Calling All Cars: Radio Dragnets and the Technology of Policing (Minnesota, 2010). Battles is also one of the co-editors of a book you should all be reading, assigning, and handing out like Halloween candy — War of the Worlds to Social Media: Mediated Communication in Times of Crisis (Peter Lang, 2013).

Here’s a taste, just to get you started.

– nv

—

Contemporary public memory of Orson Welles seems bent on remembering him as mercurial, imperious, haughty genius, driven in equal parts by ambition and artistic vision. It is hard to remember that this image of the auteur – not Welles but “Welles” – was one crafted not by the man alone, but by a host of actors and other performers, all with their own interest in attaching themselves to such a “genius.” As Welles’s reputation grew in the wake of the “War of the Worlds” broadcast, furthering his transformation into “Welles,” it was simply a matter of time before he became a fodder for another kind of auteur, the radio comedian. One of the most popular was Fred Allen, who made a career archly satirizing the cultural conventions of the day, with the radio industry itself being one of his favorite targets. “Welles” was too rich a subject to forego.

This post explores two key moments of Allen’s satire. The first came on November 9, 1939, when Allen’s show featured a comic skit, entitled “The Soundman’s Revenge, or, He Only Pulled the Trigger a Little, Because the Leading Man was Half Shot Anyway,” a radio skit that deftly mimes the Mercury/Campbell style to comic effect. The second is from three years later, October 18, 1942, when Welles himself appeared on Allen’s show, joining in the fun as the pair rehearse Les Miserables, with Welles gamely mocking “Welles.” In these two short skits, Allen and his team of writers and performers quickly dismantle what had become the more recognizable elements of the Mercury/Campbell style–as exemplified in Welles’s version of A Tale of Two Cities–including the elevation of Welles to the genius “author” of the plays, its narrative and performance techniques, and the use of sound effects.

Mercury Theater was strongly marked with the authorial imprint of the real Welles, but the legend of “Orson Welles” was also crafted quite deliberately by CBS, and then later by show sponsor Campbell’s Soup, for their own aims at cultural legitimacy. As Michele Hilmes argued, such moves were key to legitimizing the medium as operating in the “public interest” (183-88). Here is a clip from just after Campbell Soup began sponsoring the Welles program:

As other writers have pointed out, such as Debra Rae Cohen in her entry to this series, Neil Verma, and Paul Heyer, the show was among the best in emphasizing the sonic properties of radio to maximum effect in storytelling. The quality acting of members of the Mercury Theater, the music of Bernard Herrmann, the ambitious use of sound effects, and some stellar examples of adapting literary tales make the show worthy of praise.

The emotional and narrative power of Welles himself is evident in the Mercury Theater dramatization of A Tale of Two Cities. Taking on Dickens’ sprawling classic in one hour certainly demanded some creative choices. One was to open with Dr. Mannette’s letter from the Bastille prison, with Welles as Mannette emotionally dictating the words that would later serve to betray his own family.

This is contrasted against the later reading of the same letter in a courtroom scene, where the emotional poignancy of Welles’s performance is counterpointed against its dry reading as a piece of evidence.

The sound effects team from The March of Time in a 1930’s publicity photo. On the left is Ora Nichols, who would later develop sounds for The War of the Worlds.

Dynamic use of sound effects was another key element of the Mercury/Campbell style. From his work in March of Time and The Shadow, which both used sound effects to enact key narrative devices (Time varied times and locations, the Shadow’s invisibility), Welles used his own radio program to push the boundaries of what such effects could achieve. In A Tale of Two Cities, sound effects are used to punctuate key moments, none to greater effect than the final scene in which the sound of the guillotine serves as the morbid backdrop to Carton’s final, famous speech of self sacrifice:

All of these tendencies are key to Allen’s “Soundman’s Revenge,” in which Orson Welles and the Campbell’s Playhouse become “Dorson Belles” and “Finnegan’s Playhouse,” with the evening’s entertainment an adaptation of Jack and Jill fetching a pail of water.

Belles, acted by Fred Allen, tells his listeners that “My program is famous, and rightly so, for my sound effects, conceived in solitude by me.” The skit reaches ridiculous heights during a dramatization of “Jack’s” first meeting with “Jill.” As Jack and Jill wax enthusiastically at each other merely by repeating each others’ names, the host breaks in to tell listeners that “This dialogue, ladies and gentleman, is not to be found in the original Mother Goose version. It has been interprellated by Dorson Belles. We return you now to the play.”

The always potential high culture pretentiousness of Mercury/Campbell aesthetic choices are brought to the fore by the ridiculous choice of a Mother Goose nursery rhyme as the “play” within the skit. But other things do as well. The skit opens in typical Mercury first person narrative style, where Jack tells the tale from his own perspective in a ponderous, overwrought dramatic fashion. Jack does not live in postcard ready New England, he lives in a “land of penury and misery.” He does not merely make a mess while preparing his dinner, but “licks the albumen of owl’s egg off his fingers.”’

In its most pointed reference to Mercury style, the skit directly plays off a memorable moment in War of the Worlds when, as Professor Pierson narrates his travels in New Jersey, he states that “I saw something crouching in a doorway, and it rose up and became a man. A man armed with a large knife.” Here is the clip:

In similar dramatic style, Jack narrates his journey up the hill, hauling his “heavy oaken pail” and asks “What was that huddled form crouching in my path? Was it a girl? It was!”

The comic tour-de-force, however, comes with its satire of sound effects. Allen’s team goes for broke as listeners laugh along to the gradual undoing of the hapless Theodore Slade, Welles’s sound effects engineer in the skit, who is driven to madness by the excessive number of effects. Slade makes many mistakes throughout, but his errors really add up when Jack kills his father and he describes the “long arm of the law” reaching out, coming from the north on horseback, the east by train, the west by “aeroplane,” and the north by sleigh. Each description is punctuated by its appropriate sound; hooves, whistles, engines, and of course, sleigh bells.

It works the first time, but when Jack dramatically asks if he and Jill can escape each of these modes of capture, Slade plays the wrong effects. When Jack tells us he stabbed the Sherriff, Slade plays a gunshot. This time, when Belles chastises him, Slade lets loose, telling Belles that he is going “nuts,” then trying to rectify the mistake by killing the Sherriff again. Belles yells out that “this is confusing!” to which Slade retorts, “you’re telling me!” As Jill tries to continue the scene, telling us she is shooting herself, Slade plays the train whistle. Finally Jack narrates that Jill, the Sherriff, and his father are dead, and that “I alone live.” Slade replies, “yeah, but not for long,” and after listing off years worth of complaints, shoots Belles. Belles, in a pitch perfect rendition of Welles’s weekly closing of his radio show, says “This is Dorson Belles, signing off permanently. Pending rigor mortis, I remain, obediently yours.”

Perhaps Welles was offended, or perhaps he yearned to be in on the joke. He certainly seemed to relish the chance for that opportunity, when he appeared as a guest on Allen’s show, 3 years later on October 18, 1942. Here he plays along in the skewering of his own genius image, tied to his authorial control over all his projects. As the cast nervously awaits the arrival of the great “Welles,” Allen tries to calm them. Once “Welles” enters the studio, Allen himself comes in for his own ribbing. “Welles” tells him that they will be performing a new version of one of Welles’s early radio dramatizations, Les Miserables. Here Welles successfully mocks both “Welles” and Allen, insisting on sole authorship, giving an overwrought performance, using the first person singular mode of delivery, and most humorously by reducing Allen’s contribution to a few sound effects.

In those few moments where Welles himself cannot help from laughing along with the mockery, “Welles” becomes Welles, and we in the audience get to laugh with, not at, the man.

While CBS, Campbell Soup, and the press turned Welles into “Welles,” Allen undermined that move, puncturing the grandiose myth, a project in which Welles himself was only too willing to participate. By breaking it down to its constituent elements, the “Soundman” and Les Miserables skits celebrate the unique style of the Mercury/Campbell radio productions. Yet, they also pierce its cultured veneer by pointing to the unsung efforts of the always-necessary team to make radio performances work, and skewering the pretentiousness of the program’s extra-textual discourses. In the process Welles and Allen mutually constructed and deflated each other’s reputation as radio geniuses.

—

Featured Image: Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins sharing a laugh on the set of The Trial.

—

Kathleen Battles is Associate Professor and Graduate Director in the Department of Communication and Journalism at Oakland University (MI not CA). She is recently co-editor (with Joy Hayes and Wendy Hilton-Morrow) of War of the Worlds to Social Media: Mediated Communication in Times of Crisis (Peter Lang, 2013), a volume that seeks to draw connections between the War of the Worlds broadcast event and contemporary issues surrounding new media. She is also the author Calling All Cars: Radio Dragnets and the Technology of Policing (University of Minnesota Press, 2010). Her research interests include Depression era radio cultures, the interrelationship between radio, telephones, and automobiles, media and space/time, the historical continuities between “old” and “new” media, and contemporary issues surrounding sexuality and the media.

—

Want to catch up on the Mercury to Mars series?

Want to catch up on the Mercury to Mars series?

Click here to read Tom McEnaney’s thoughts on the place of Latin America in Welles’s radio work.

Click here to read Eleanor Patterson’s reflections on recorded re-releases of the “War of the Worlds” broadcast.

Click here to read Debra Rae Cohen’s thoughts on vampire media in Orson Welles’s “Dracula.”

And click here to read Cynthia B. Meyers on the challenges and rewards of teaching WOTW in the classroom.

While I’ve still got you here … be sure to join our WOTW anniversary Facebook group. Next month we’re planning exciting events around the anniversary of the Martian Panic on October 30, 2013 from 7-10 EST, and hoping to get as many of you as we can to liveTweet the Invasion broadcast. Sign up to join in!

Soundscapes of Narco Silence

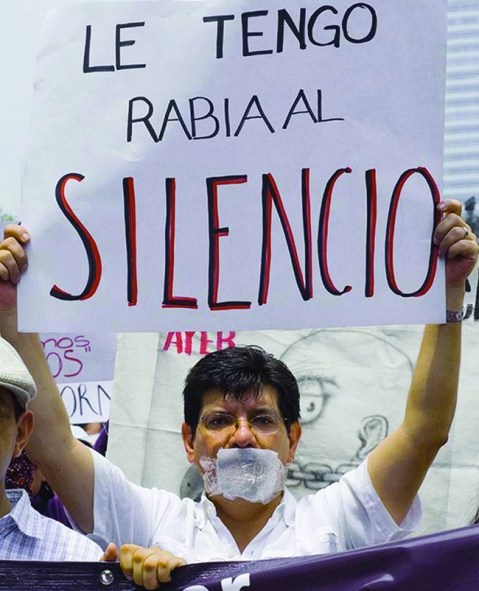

Journalists protest in silent march in Mexico City, Courtesy of the Knight Foundation

Since the drug war began, the lives of approximately 95,000 people have been claimed, with an estimated total of 26,000 disappearances (“Continued Humanitarian Crisis at the Border” June 2013 Report). At the University of Texas, Pan American – an institution located 25 miles north of Reynosa, Mexico (a Mexican city that has been hard hit by drug violence in recent years) – I teach students who have been dramatically impacted by drug war violence. Many have close relatives affected or hear horrific stories of those who have been kidnapped by the cartels; many fear traveling to Mexico to visit loved ones as a result and, in some cases, they report having relatives involved in the drug cartel business. Dinorah Guerra, psychotherapist and head of the Red Cross in Reynosa, describes the devastating psychological and physical toll: “There is a huge risk for people’s self esteem. They cannot speak about what they have seen or what they have heard. [They] lose [themselves] and lose [their] identity” (qtd. in Pehhaul 2010).

I name the space of the drug war and its resulting terror in the U.S.-Mexico border the “soundscape of narco silence.” This soundscape includes death and intimidation, from the brutal killings of news reporters by cartel members to the decapitation of citizen-activists who use online media to alert communities of narco checkpoints. It also consists of those powerful acts that call attention to silence as a tactic of terror. The Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity, for instance, brought together tens of thousands of people in Mexico to speak out against drug violence through silent marches. Cultural productions, such as narcocorridos, or contemporary drug ballads that document the cross-border drug economy, also become part of the soundscape. The narcocorridos function as a powerful critical response to silence and fear because they enable those in Mexican society, as Jorge Castañeda, author of El Narco: La Guerra Falllida, explains, “to come to terms with the world around them, and drug violence is a big part of that world. The songs are born out of a traditional Mexican cynicism: This is our reality, we’ve gotten used to it” (Qtd. in Josh Kun 2010).

In this blog post, I focus on the role of U.S. Latina/o theater produced in the South Texas border region as it responds to the soundscape of narco silence. Building on David W. Samuels, Louis Meintjes, Ana Maria Ochoa, and Thomas Porcello’s definition of “soundscapes” in “Soundscapes: Towards a Sounded Anthropology” as “the material spaces of performance and ceremony that are used or constructed for the purpose of propagating sound” (330), I suggest that soundscapes of silence in theater function as material spaces of performance that focus the public’s attention on silence – with the intent of intervening in acts that propagate silence and fear. Soundscapes of narco silence are characterized not only by violence and terror, but by cultural productions that function as forms of critical resistance – those works that focus the publics’ attention on the economy of silence and fear that fuels the drug war, and in the process, enable communities to cope with narco violence.

Journalists protest in silent march in Mexico City, Courtesy of the Knight Foundation

To closely listen to the soundscape of narco silence, I engage with the play script and production of Tanya Saracho’s play El Nogalar at South Texas College Theatre (STC) under the direction of Joel Jason Rodriguez in McAllen, Texas in June 2013. The play was first produced at the Goodman Theater in Chicago in April 2011, with a West Coast premiere at the Fountain Theater in Los Angeles in January 2012. I critically analyze the STC Theatre production’s incorporation of a multi-genre soundtrack that included narcocorridos, rancheras, and nortec (norteño + techno). I argue that this soundtrack focused audiences’ attention not only on the devastating effects of silence, but also the function of silence as a form of capital for those most excluded in society. I also offer a brief critical listening of the script’s rendering of silence through character dialogue and stage directions.

El Nogalar tells the story of an upper-class Mexican family comprised of three generations of women (Maité, Valeria, and Anita) whose land and home in the fictionalized estate of Los Nogales in Nuevo Leon, Mexico, and its adjacent nogalar (pecan orchard), are under threat by the maña (drug cartels) moving into the region. The play focuses on the women’s responses to the drug war economy as a result of their different relationships to home (both their estate and the space of Mexico). It also centers the experiences of Dunia, their maid, and López, a former field worker who now works for the maña.

STC Theater Production of El Nogalar. Photo Credit: Miguel Salazar

Cecilia Ballí, in her article “Calderón’s War: The Gruesome Legacy of Mexico’s Antidrug Campaign,” explains the particular circumstances of marginalized men in this society: “The worst casualties of this ‘civil war’ were the estimated 7 million young men to whom society had closed all doors, leaving them the options of joining a drug gang or of enlisting in the military, both of which assured imprisonment of death” (January 2012, 48). With the characters López and Dunia, the play asks audiences then to listen to the impact of the drug war on the most vulnerable populations in Mexico and the US-Mexico border region.

The play script conveys how “narco silence” can be used by those who either seek to preserve traditional class hierarchies (the story of the matriarch Maité) or to survive and profit in the new drug economy (the story of López). “Narco silence,” a term coined by reporter Jonathan Gibler in his book To Die in Mexico, refers to “not the mere absence of talking, but rather the practice of not saying anything. You may talk as much as you like, as long as you avoid the facts. Newspaper headlines announce the daily death toll, but the articles will not tell you anything about who the dead were, who might have killed them or why. No detailed descriptions based on witness testimony. No investigation” (2011, 23). In an early exchange between López and Dunia, López defends “narco silence” as a strategy of survival:

STC Theater Production of El Nogalar. Photo Credit: Miguel Salazar

DUNIA: Why are you the only one they leave alone, Memo?

LÓPEZ:….

DUNIA: All the men your age. Killed. Why Memo? (Beat).

LÓPEZ: Because I know when to keep my mouth shut which is not something I can say for you….

DUNIA: So that’s all it takes to be best of friends with the Maña? That doesn’t seem so hard to do? (American Theatre Magazine July/August 2011, 74).

Later in the play, Dunia, heeding López’s advice, offers a powerful observation of how “narco silence” enables her community to cope with death: “We all just walk around like we’re a movie on mute. You can see people’s mouths moving but all you hear is the static (my italics)” (American Theatre Magazine July/August 2011, 73-74).

The STC Theatre production enhanced the script’s soundscape of narco silence through its sound design, with a soundtrack that included rancheras, narcocorridos, norteño and nortec. This music provided audiences with a connection to the world of Los Nogales and captured each character’s process of coping with narco violence. For example, Maité’s soundtrack consists of several rancheras, such as Lola Beltran singing “Los Laureles” and Chavela Vargas’s powerful rendition of “Que te vaya Bonito.” Beltran’s “Los Laureles” – a cancion ranchera that includes Beltran’s powerful female vocals and mariachi orchestra instrumentation – invites audiences to hear Maité’s nostalgia and desire for an idealized Mexican society and her wish to preserve traditional class hierarchies.

.

Vargas’s powerful rendition of “Que te vaya Bonito” captures Maite’s pain and suffering as she loses her home to the cartels. In Vargas’s version of “Que te Vaya Bonito” – a song about love and abandonment – audiences hear Vargas’s choking and sobbing voice, accompanied by a single guitar.

.

Vargas’s voice conveys, what Lorena Alvarado powerfully argues, is “the body’s dilemma between the hysteria of sobbing and the intelligibility of words, between resignation and retribution” (2010, 4). Vargas’s powerful singing also conveys, as Alvarado further describes, “un nudo en la garganta,” a common expression in Spanish that describes “the knot in the throat, when one cannot speak because words will not come out, but the desperate, or quiet, breath of tears” (Alvarado 2010, 5).

To sonically register the drug cartel economy and lifestyle underlying the “new” Los Nogales, the soundtrack also included narcocorridos. The first sounds we hear in the play are from the narcocorrido “El Carril Número Tres” – which includes two acoustic guitars and an electric bass – by Los Cuates de Sinaloa.

.

“El Carril Número Tres” – tells the story of a secret “lane number three” that allows a Mexican drug lord to freely go back and forth between the US and Mexico because he makes a deal with the CIA and DEA. With this focus on the US government’s involvement in the drug trade, the song centers how silences north of the US-Mexico border have perpetuated drug violence.

The music also included nortec, with songs by the Mexican Institute of Sound, particularly the track “Mexico,” which is a critique of the Mexican government’s complicity with the narcos.

.

With “Mexico,” audiences hear a fusion of norteño, electronic, and hip-hop with lyrics that use the symbols of Mexican national identity and culture to focus the public’s attention on violence and terror. With the lyrics “green like weed, white like cocaine, red your blood” (referencing the Mexican flag) and “at the sound of the roar of the cannon” (alluding to the national anthem), the song powerfully invokes the visual and sonic soundscape of violence that terrorize Mexican residents. With this charged critique of government corruption, “Mexico” momentarily interrupts the soundscape of narco silence rendered in the play script and rest of the soundtrack.

Ultimately, the production’s combination of rancheras, narcocorridos, and nortec captured the class tensions in Mexican society and emphasized the play’s critique of class structures that have enabled drug war violence to persist. With this range of music, the director explains he wanted to “maneuver between the [various] aspects of [the story]: the nostalgia, the corridos, the narcocorridos, and also this fusion of saying ‘we want something more,’ and so that was the whole aspect of it; the blending of the old, the new, and what the present is” (Interview with author July 2013).

The production also deliberately incorporated the sound of silence, particularly in the final scene. By the end, López buys the Los Nogales estate, thereby increasing his class status and social power. Saracho’s stage directions in this final moment indicate “an interpretive sound of trees falling. Now don’t go cueing chainsaws because it’s not literal. Just make me feel trees are falling. Along with the upper class” (87). The play’s reference to the staging of “an interpretive sound of trees falling” brings to mind the philosophical question: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” We might then interpret the final sounds of El Nogalar as inviting audiences to listen attentively to the soundscape of narco silence, implicating audiences as social actors in the politics of the drug war that continue to devastate Mexican society.

—

Featured Image: Journalists Protest against rising violence during march in Mexico, Courtesy of the Knight Foundation

—

Marci R. McMahon received her Ph.D. from the University of Southern California with affiliations in the Department of American Studies and Ethnicity. She is an assistant professor at the University of Texas, Pan American, where she teaches Chicana/o literature and cultural studies, gender studies, and theater and performance in the Departments of English and Mexican American Studies. She is the author of Domestic Negotiations: Gender, Nation, and Self-Fashioning in US Mexicana and Chicana Literature and Art published by Rutgers University Press’ Series Latinidad: Transnational Cultures in the United States (May 2013). Her essays on Chicana literature and cultural studies have been published in Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies; Chicana/Latina Studies: The Journal of MALCS; and Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies. Her second book project, Sounding Latina/o Studies: Staging Listening in US Latina/o Theater explores how contemporary Latina/o drama uses vocal bodies and sound to engage audiences with recurring debates about nationhood, immigration, and gender.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Listening to the Border: “’2487’: Giving Voice in Diaspora” and the Sound Art of Luz María Sánchez–D. Ines Casillas

Quebec’s #casseroles: on participation, percussion and protest–Jonathan Sterne

Deejaying her Listening: Learning through Life Stories of Human Rights Violations— Emmanuelle Sonntag and Bronwen Low

Recent Comments