The Cyborg’s Prosody, or Speech AI and the Displacement of Feeling

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It kicked off with Amina Abbas-Nazari’s post, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice. Then, Golden Owens took a deep historical dive into the racialized sound of servitude in America and how this impacts Intelligent Virtual Assistants. Last week, Michelle Pfeifer explored how some nations are attempting to draw sonic borders, despite the fact that voices are not passports. Today, Dorothy R. Santos wraps up the series with a meditation on what we lose due to the intensified surveilling, tracking, and modulation of our voices. [To read the full series, click here] –JS

—

In 2010, science fiction writer Charles Yu wrote a story titled “Standard Loneliness Package,” where emotions are outsourced to another human being. While Yu’s story is a literal depiction, albeit fictitious, of what might be entailed and the considerations that need to be made of emotional labor, it was published a year prior to Apple introducing Siri as its official voice assistant for the iPhone. Humans are not meant to be viewed as a type of technology, yet capitalist and neoliberal logics continue to turn to technology as a solution to erase or filter what is least desirable even if that means the literal modification of voice, accent, and language. What do these actions do to the body at risk of severe fragmentation and compartmentalization?

I weep.

I wail.

I gnash my teeth.

Underneath it all, I am smiling. I am giggling.

I am at a funeral. My client’s heart aches, and inside of it is my heart, not aching, the opposite of aching—doing that, whatever it is.

Charles Yu, “Standard Loneliness Package,” Lightspeed: Science Fiction & Fantasy, November 2010

Yu sets the scene by providing specific examples of feelings of pain and loss that might be handed off to an agent who absorbs the feelings. He shows us, in one way, what a world might look and feel like if we were to go to the extreme of eradicating and off loading our most vulnerable moments to an agent or technician meant to take on this labor. Although written well over a decade ago, its prescient take on the future of feelings wasn’t too far off from where we find ourselves in 2023. How does the voice play into these connections between Yu’s story and what we’re facing in the technological age of voice recognition, speech synthesis, and assistive technologies? How might we re-imagine having the choice to displace our burdens onto another being or entity? Taking a cue from Yu’s story, technologies are being created that pull at the heartstrings of our memories and nostalgia. Yet what happens when we are thrust into a perpetual state of grieving and loss?

Humans are made to forget. Unlike a computer, we are fed information required for our survival. When it comes to language and expression, it is often a stochastic process of figuring out for whom we speak and who is on the receiving end of our communication and speech. Artist and scholar Fabiola Hanna believes polyvocality necessitates an active and engaged listener, which then produces our memories. Machines have become the listeners to our sonic landscapes as well as capturers, surveyors, and documents of our utterances.

The past few years may have been a remarkable advancement in voice tech with companies such as Amazon and Sanas AI, a voice recognition platform that allows a user to apply a vocal filter onto any human voice, with a discernible accent, that transforms the speech into Standard American English. Yet their hopes for accent elimination and voice mimicry foreshadow a future of design without justice and software development sans cultural and societal considerations, something I work through in my artwork in progress, The Cyborg’s Prosody (2022-present).

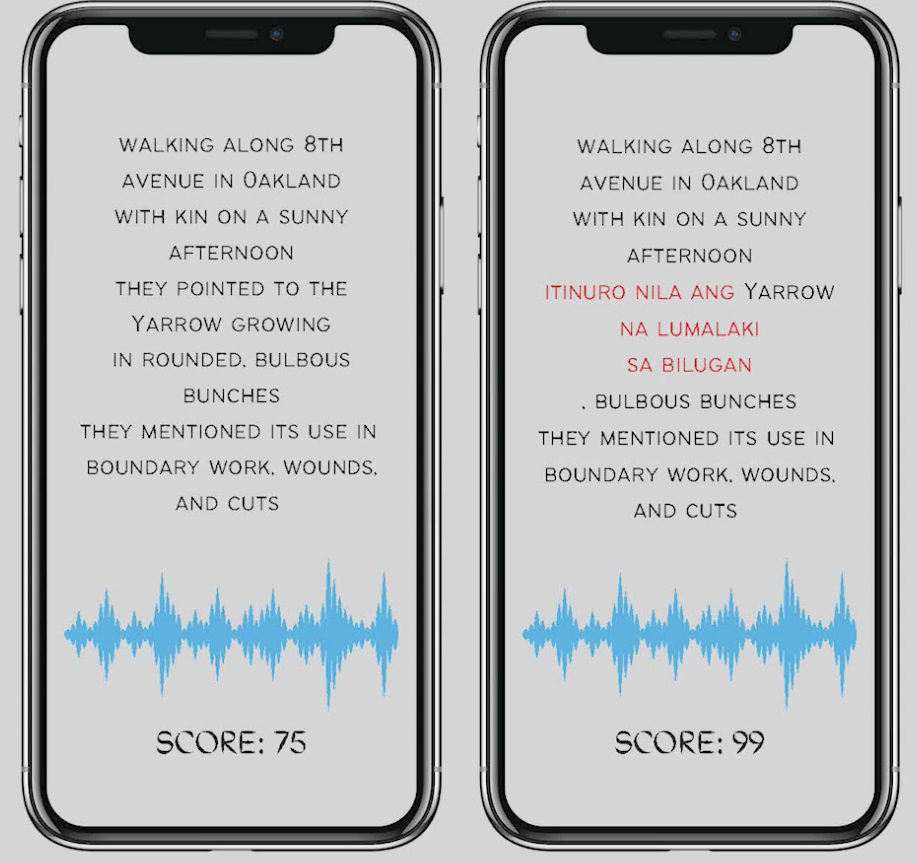

The Cyborg’s Prosody is an interactive web-based artwork (optimized for mobile) that requires participants to read five vignettes that increasingly incorporate Tagalog words and phrases that must be repeated by the player. The work serves as a type of parody, as an “accent induction school” — providing a decolonial method of exploring how language and accents are learned and preserved. The work is a response to the creation of accent reduction schools and coaches in the Philippines. Originally, the work was meant to be a satire and parody of these types of services, but shifted into a docu-poetic work of my mother’s immigration story and learning and becoming fluent in American English.

Even though English is a compulsory language in the Philippines, it is a language learned within the parameters of an educational institution and not common speech outside of schools and businesses. From the call center agents hired at Vox Elite, a BPO company based in the Philippines, to a Filipino immigrant navigating her way through a new environment, the embodiment of language became apparent throughout the stages of research and the creative interventions of the past few years.

In Fall 2022, I gave an artist talk about The Cyborg’s Prosody to a room of predominantly older, white, cisgender male engineers and computer scientists. Apparently, my work caused a stir in one of the conversations between a small group of attendees. A couple of the engineers chose to not address me directly, but I overheard a debate between guests with one of the engineers asking, “What is her project supposed to teach me about prosody? What does mimicking her mom teach me?” He became offended by the prospect of a work that de-centered his language, accent, and what was most familiar to him.The Cyborg’s Prosody is a reversal of what is perceived as a foreign accented voice in the United States into a performance for both the cyborg and the player. I introduce the term western vocal drag to convey the caricature of gender through drag performance, which is apropos and akin to the vocal affect many non-western speakers effectuate in their speech.

The concept of western vocal drag became a way for me to understand and contemplate the ways that language becomes performative through its embodiment. Whether it is learning American vernacular to the complex tenses that give meaning to speech acts, there is always a failure or queering of language when a particular affect and accent is emphasized in one’s speech. The delivery of speech acts is contingent upon setting, cultural context, and whether or not there is a type of transaction occurring between the speaker and listener. In terms of enhancement of speech and accent to conform to a dominant language in the workplace and in relation to global linguistic capitalism, scholar Vijay A. Ramjattan states in that there is no such thing as accent elimination or even reduction. Rather, an accent is modified. The stakes are high when taking into consideration the marketing and branding of software such as Sanas AI that proposes an erasure of non-dominant foreign accented voices.

The biggest fear related to the use of artificial intelligence within voice recognition and speech technologies is the return to a Standard American English (and accent) preferred by a general public that ceases to address, acknowledge, and care about linguistic diversity and inclusion. The technology itself has been marketed as a way for corporations and the BPO companies they hire to mind the mental health of the call center agents subjected to racism and xenophobia just by the mere sound of their voice and accent. The challenge, moving forward, is reversing the need to serve the western world.

A transorality or vocality presents itself when thinking about scholar April Baker-Bell’s work Black Linguistic Consciousness. When Black youth are taught and required to speak with what is considered Standard American English, this presents a type of disciplining that perpetuates raciolinguistic ideologies of what is acceptable speech. Baker-Bell focuses on an antiracist linguistic pedagogy where Black youth are encouraged to express themselves as a shift towards understanding linguistic bias. Deeply inspired by her scholarship, I started to wonder about the process for working on how to begin framing language learning in terms of a multi-consciousness that includes cultural context and affect as a way to bridge gaps in understanding.

Or, let’s re-think this concept or idea that a bad version of English exists. As Cathy Park Hong brilliantly states, “Bad English is my heritage…To other English is to make audible the imperial power sewn into the language, to slit English open so its dark histories slide out.” It is necessary for us all to reconfigure our perceptions of how we listen and communicate that perpetuates seeking familiarity and agreement, but encourages respecting and honoring our differences.

—

Featured Image: Still from artist’s mock-up of The Cyborg’s Prosody(2022-present), copyright Dorothy R. Santos

—

Dorothy R. Santos, Ph.D. (she/they) is a Filipino American storyteller, poet, artist, and scholar whose academic and research interests include feminist media histories, critical medical anthropology, computational media, technology, race, and ethics. She has her Ph.D. in Film and Digital Media with a designated emphasis in Computational Media from the University of California, Santa Cruz and was a Eugene V. Cota-Robles fellow. She received her Master’s degree in Visual and Critical Studies at the California College of the Arts and holds Bachelor’s degrees in Philosophy and Psychology from the University of San Francisco. Her work has been exhibited at Ars Electronica, Rewire Festival, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and the GLBT Historical Society.

Her writing appears in art21, Art in America, Ars Technica, Hyperallergic, Rhizome, Slate, and Vice Motherboard. Her essay “Materiality to Machines: Manufacturing the Organic and Hypotheses for Future Imaginings,” was published in The Routledge Companion to Biology in Art and Architecture. She is a co-founder of REFRESH, a politically-engaged art and curatorial collective and serves as a member of the Board of Directors for the Processing Foundation. In 2022, she received the Mozilla Creative Media Award for her interactive, docu-poetics work The Cyborg’s Prosody (2022). She serves as an advisory board member for POWRPLNT, slash arts, and House of Alegria.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Your Voice is (Not) Your Passport—Michelle Pfeifer

“Hey Google, Talk Like Issa”: Black Voiced Digital Assistants and the Reshaping of Racial Labor–Golden Owens

Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication –Amina Abbas-Nazari

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–Steph Ceraso

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

Look Who’s Talking, Y’all: Dr. Phil, Vocal Accent and the Politics of Sounding White–Christie Zwahlen

Listening to Modern Family’s Accent–Inés Casillas and Sebastian Ferrada

Sounding Out! Podcast #57: The Reykjavik Sound Walk

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD: The Reykjavik Sound Walk

SUBSCRIBE TO THE SERIES VIA ITUNES

ADD OUR PODCASTS TO YOUR STITCHER FAVORITES PLAYLIST

Standing in front of our rented apartment in Túngata, a residential street just a few blocks from central Reykjavík, I am struck by the stillness of the city that surrounds me. Having lived most of my life in the densely-populated suburbs of northern New Jersey, my experience of urban soundscapes has typically been frenetic and noisy. Here, even the busiest parts of town seem subdued. It’s a pleasant contrast. At 8AM on a weekday, the quietness is eerily enveloping, broken only occasionally by a gust of arctic wind, a passing car, or a neighbor closing her door and setting off for work.

Quiet tranquility and natural beauty have attracted a growing number of tourists to Iceland in recent years, my wife and I included. With only 330,000 people inhabiting an area roughly the size of Kentucky (and two-thirds of those settled in and around Reykjavík), one needn’t venture far out into Iceland’s otherworldly landscape to feel far removed from civilization – like exploring a distant planet. While the island may be still now, the belated realization that Iceland’s bizarre terrain, its vast lava fields, meandering fissures, and Dr. Seuss rock formations are the result of earth-shattering eruptions – like Eyjafjallajökull in 2010, Bárðarbunga in 2014-15, or the more recent rumblings around Katla – can be a little unnerving. Travelling through the Icelandic countryside, one imagines the thundering cracks, seething magma, and the infernal growl of the awesome geophysical forces that churned up these vast panoramas.

To a certain extent, the absence of sound here heightens a sense of the sublimity of the world around us; that from certain perspectives, nature is fundamentally ineffable – incapable of being fully represented by language, data, or art. Sound, I think, can complicate this experience. On the one hand, the extraordinary sounds of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, of great storms, or the roiling of heavy seas, contribute to the overwhelming experience of the grand and fantastic. On the other, these sounds, like perhaps the everyday noise of a busy street corner, may also break the spell by yielding up the audibly familiar. Wandering around Reykjavík at this early hour, a settlement that has clung defiantly to a desolate rock in the North Atlantic for over 1000 years, I become acutely aware of each new sound to disrupt the ethereal silence. Each of these, even the most mundane and urban, seems to take on larger significance and intention as audible signs of the ways in which human beings have forged order and meaning from a wild and indifferent world.

But for now, all remains quiet, and the island’s primordial silence seems to reach even into the capital itself. Of course, Reykjavík is a vibrant international city resonating with the familiar sounds of urban life. But at certain times the quietness that seems to subsume everything else – a subtle reminder of the relatively small scale and frailty of the human compared to the geological.

Soon enough however, as I walk up Túngata there’s a siren in the distance, and the neighborhood begins to echo with the sounds of children playing in the yard at Landakotsskóli, one of Iceland’s oldest schools. I follow the street as it arcs towards the city center, passing several foreign embassies and the imposing gothic edifice of Dómkirkja Krists Konungs. A few other cars motor past and there’s a brief gust of cold wind, but these are momentary disruptions. Soon enough the world returns to the now-familiar stillness.

Grafitti in Reykjavik. Image by Rog01 @Flickr CC-BY-NC-SA.

But the sounds of morning traffic pick up a bit as I walk further down the hill – the rush of passing cars, the groan of a utility truck turning off a side street, and the muffled sounds of a radio floating from a car window. At its end, Túngata bends to the left at the bottom of the hill, where I see a large excursion bus stopped in front of a hotel, and a knot of tourists quietly talking nearby. It’s time for morning pickups, and the idling of these busses, and the hushed, expectant voices of day-trippers outside hotels and guesthouses around the city turn out to be common vignettes along my morning walk. They’re a reminder of the vast growth in tourism this year, which is expected to increase 29% over 2015 to 1.6 million foreign visitors.

Continuing straight onto Kirkjustrӕti, I pass the Alþingishúsið (Parliament House) on my right, and Austurvӧllur, a large public square on my left. The place is relatively quiet now. The cafes lining Vallarstrӕti and Pósthússtrӕti are closed, and there are only a handful of people walking through the square. Later on, the cafes will be buzzing with patrons enjoying the balmy (for Iceland) weather and the long hours of sunlight.

But aside from the nightlife, Austurvӧllur’s proximity to Parliament means that historically it’s been a focal point of political protest in Reykjavík. Two months before our visit, some 24,000 people crowded into this space to demand the resignation of Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, who was revealed by the Panama Papers to have undisclosed connections with an offshore shell company with interest in failed Iceland banks. Walking past the square today, I can only imagine the chants, claps, whistles, shouts, barricade-banging, and yogurt-throwing of Icelanders expressing their collective frustration with corrupt officials.

Construction in Reykjavik. Image by Patrick Rasenberg @Flickr CC BY-NC.

This morning however, apart from the early morning sound of chirping birds and pedestrian commuters, there’s a bit of construction going on here – I can hear a few landscapers and a pair of contractors clanking and clunking as they lay out equipment for work on a building next to the Alþingishúsið. From these men and others I pass along this stretch of road, I hear the hushed and slightly groggy speech of early morning. The talk is all in Icelandic of course, a language whose place and street names I valiantly try to pronounce when I visit. Icelandic is a notoriously difficult language for foreigners in general, and its tongue-twisting staccato and subtle consonants, not to mention its intimidating alphabet, usually leave my mouth sounding a bit too awkwardly Jersey (as you can hear for yourself in this podcast!).

Continuing on my walk, I follow Pósthússtrӕti as it threads around Dómkirkjan and out to Lӕkjargata, the main avenue in this section of town. Here, the soundscape is more typically urban. The sound of trucks and cars passing, a bus groaning into gear as it pulls out into traffic, the multi-lingual chatter of pedestrians at a crosswalk, a group of teenage volunteers chatting in Icelandic as they do groundskeeping work near the Stjórnarráðið government offices, all speak the language of a city’s morning routine.

Street art in Reykjavik. Image by Toni Syvänen @Flickr CC BY-NC-SA.

Bankastrӕti, the main commercial district, is also coming to life. It’s still early, and most shops are closed, but heading east up the street, I hear a few snatches of conversations in Icelandic and American English – and there seems to be more of the latter than I remember from the last time we visited, testament to Iceland’s growing attraction for U.S. tourists. All along Bankastrӕti, the sounds of lively conversation, music, and the clinking of tableware floats out of open doors as people pop in and out of cafes and restaurants for breakfast and morning coffee. As I bear right on Skólavӧrðustigur and up the hill towards Hallgrímskirkja – the Lutheran church that dominates the city skyline like an art deco rocket ship – these sounds start to thin out again. Apart from a passing car or pedestrian, and the occasional rumbling of a tour bus or ATV, I am left in the comforting hush of a Reykjavík morning.

At the top of the hill, the large stone plaza before Hallgrímskirkja echoes with the clattering sounds of workers hammering at the roof of a nearby building, as the great green statue of Leifur Erikíksson silently watches on. I turn left on Frakkastígur and head downhill towards Faxa Bay, which looms in the middle distance. Frakkastígur turns out to be the noisiest stretch of my walk: there’s the roofers; the slapping of lanyards on the flagpoles that surround Hallgrímskirkja; the busy bakery where I buy morning croissants surrounded by Beatles music, the English and Icelandic chatter of customers, and the pounding, rolling, and cutting of dough; and finally the two large construction sites that I pass between Laugavegur and Hverfisgata streets. Here, the motoring of earthmovers, the shrieking of a circular saw, and the pounding of a massive pile driver jar the neighborhood with an intense mechanized racket.

I’ve noticed a fair amount of construction around Reykjavík this trip. The skyline bristles with cranes. It’s another marker of the booming tourism industry, and its complicated place in the Icelandic economy. Since the financial collapse of 2008, there’s been pent-up demand for residential housing. But with the local construction industry strained from the current spate of hotel building, it’s been difficult to find builders to work on residential projects. What I hear around me is a sign that Iceland’s economy has improved, but it’s also a reminder that improvement sometimes makes life more difficult for local residents.

Sculpture on the shore of Reykjavik. Image by Ainhoa Sánchez Sierra @Flickr CC-BY-NC-SA.

The sounds of heavy construction fade as I wind my way down to the bay and cross over Sӕbraut to the promenade that lines the shore. Like any highway, at this point in the morning Sӕbraut fairly hums with commuter traffic; here, the ambient sound of suburbanites making the morning drive to work, complete with attendant sound of brakes, horns, and Icelandic drive-time radio mix with the rushing sound of wind rolling off the waterfront. Walking along the promenade now, I pass a few joggers and bicyclists as a walk over to Harpa, the newly-built glass and steel concert hall that is home to the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra and which, every autumn, becomes a focal point of the week-long Iceland Airwaves music festival. It’s this annual event, I muse, that should be the subject of a future sound walk (for me or someone else) – five days in which Reykjavík pulsates with the sound and music of dozens of bands playing formal and informal shows at venues, cafes, bookstores, and basements around the city.

From a large dig site next to Harpa (the possible site of yet another hotel), I cross back over Sӕbraut to the clicking sounds of a crossing signal for blind pedestrians. I pass Bӕjarins Beztu Pylsur (The Best Hot Dog in Town), which is closed for the morning, and walk back into the city center, which is by now clearly awake and buzzing with locals and tourists. After stopping in a 24-hour supermarket for some morning milk, I walk east on Austurstrӕti past the Laundromat Café and other restaurants that are now busy serving the breakfast crowd.

Up through Ingólfstorg square (which appears to double as a skate park, but is right now a stopping point for a walking tour group), south on Aðalstrӕti, and around the turn by the Reykjavík Settlement Museum, I’m soon walking back up through the quiet neighborhood lining Túngata.

—

Featured Image by SambaClub | Camisetas com conteúdo (a t-shirt site) @Flickr CC BY.

—

Andrew J. Salvati is a Media Studies Ph.D. candidate at Rutgers University. His interests include the history of television and media technologies, theory and philosophy of history, and representations of history in media contexts. Additional interests include play, authenticity, the sublime, and the absurd. Andrew has co-authored a book chapter with colleague Jonathan Bullinger titled “Selective Authenticity and the Playable Past” in the recent edited volume Playing With the Past (2013), and has written a recent blog post for Play the Past titled “The Play of History.”

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Podcast #37: The Edison Soundwalk–Frank Bridges

This is What it Sounds Like……..On Prince and Interpretive Freedom–Benjamin Tausig

Soundwalking New Brunswick, NJ and Davis, CA–Aaron Trammell

Recent Comments