As Loud As I Want To Be: Gender, Loudness, and Respectability Politics

Editor’s Note: Here’s installment #2 of Sounding Out!‘s blog forum on gender and voice! Last week we hosted Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book; she introduced us to the idea of the gendered soundscape, which she uses in her analysis on women’s radio speech from the 1930s to the 1950s. In the next few weeks we’ll have SO regular writer Regina Bradley, with a look at how music is gendered in Shonda Rhimes’ hit show Scandal, A.O. Roberts with synthesized voices and gender, Art Blake with his reflections on how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage, and lastly Robin James with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy.

Editor’s Note: Here’s installment #2 of Sounding Out!‘s blog forum on gender and voice! Last week we hosted Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book; she introduced us to the idea of the gendered soundscape, which she uses in her analysis on women’s radio speech from the 1930s to the 1950s. In the next few weeks we’ll have SO regular writer Regina Bradley, with a look at how music is gendered in Shonda Rhimes’ hit show Scandal, A.O. Roberts with synthesized voices and gender, Art Blake with his reflections on how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage, and lastly Robin James with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy.

As I planned for SO!’s February forum, I wondered about my own connection to the topic: how is the loudness of a voice gendered? Does it matter who we call “loud”? As a Latina, I’m familiar with the stereotypes of the loud Latina, and as a Puerto Rican I faced them at every gathering. So for this week I decided to reflect upon my experiences in a personal essay. Lean in, close your eyes, and don’t let the voices startle you.–Liana M. Silva, Managing Editor

—

I was 22 years old when someone called me deaf. I was finishing my bachelor’s degree at the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras campus. After four years of living in San Juan, I still hadn’t gotten used to the class and race microaggressions I encountered regularly because I was a brown girl who grew up in the country and was going to school in the urban capital, el área metropolitana. These microaggressions were usually assumptions about who I was based on how I talked: I called pots a certain way, I referred to nickels in another way, and I couldn’t keep my voice down–all indications, according to my “urban” friends, that I grew up in the country. But being called “deaf” was a new one.

My boyfriend at the time had no cellphone, and his mother would call me regularly to see if he was on his way home from a gig or to ask him to run an errand. She and I were not close, but we were cordial. I always felt we didn’t click on some level. This particular weekend day, she had called to ask if he had left San Juan already to come visit her, and I told her I had just seen him that morning before he left. Somehow she and I went from small talk into a conversation.

In my head, I thought I was making headway with her and that this was a huge step forward in our relationship. We talked about his gig the night before, about how my family was doing, things like that. Then she asked me if my family had a medical history of people losing their hearing. “No? I don’t think so. Why do you ask?” I said in Spanish.

“Because you talk so loud, and so do your father and your sister. Your mom isn’t loud.”

That was over 10 years ago, but the comment still stings. I am certain that wasn’t the only time someone called me “loud” or pointed out the tone of my voice, but it’s the one time that still rings in my ears when I think about the intersection of gender and sound. It wasn’t just that I spoke at a high volume, it was that I was a woman who spoke at a high volume. I was the girlfriend who was loud.

Of course we’re not born loud- or soft-speakers – we learn to use the volume level that prevails in our culture, and then turn it up or lower it depending on our subculture and peer group.

-Anne Karpf, The Human Voice

What does “loud” mean, anyway? Denotations fade into connotations. As I write this, I struggle to think of how to describe loud in a way that doesn’t feel negative. Because every time I think of “loud” its negative connotations float up to the surface. Just take this Merriam-Webster online dictionary entry for “loud.” Aside from the reference to volume, “loud” also means sounds that are offensive, obtrusive—annoying.

To be fair, I’ve always been self-conscious of my voice, and not in the way most people hate the sound of their voice. I always felt my voice was not girly enough. I always felt as a teenager and a young adult not “pretty” enough, not thin enough, not “feminine” enough, so my insecurities also extended to my voice.

Growing up, I heard people tell me time and time again to keep my voice down, that I was talking too loud, that people next door could hear me, et cetera. Grandparents, cousins, parents, friends: I got it from every corner. Shush. But I don’t recall anybody saying that about the boys/men I hung out with. Add to that the comments I got about my appearance: “you’re too fat,” “your hair is too frizzy,” ‘you’re ugly.” I associated being loud with being unattractive. Just another flaw.

It’s no coincidence then that describing a woman as loud is almost never said as a compliment. Although a man can be loud—he might even be expected to have a deep, booming, commanding voice, as the above video describes—when a woman is described as loud, it’s almost never in a good light. Karpf mentions in The Human Voice: The Story of a Remarkable Talent that “Loudness certainly seems to be judged differently depending on the sex of the speaker. Talking loudly is considered an act of aggression in women, but in men as no more than they’re entitled to.” In other words, society deems men to be allowed to be loud, and by extension loudness comes off as a masculine feature. So loudness, something that at its base means high volume, ends up being constructed as more than just decibels. Women who are “loud” become noisy, rude, unapologetic, unbridled.

Mija pero que duro tu hablas.

In Puerto Rico, the word for “loud” was alto (high) but also duro (hard). I knew early on that when someone told me that I spoke duro they didn’t mean it in a kind way. The voice was described as hard, harsh, shards of glass. It hurt to be called loud. It hurt to be called hard. Especially when you understand that society accepts only certain ways of being a woman: soft, delicate, fragile, dainty. It was never meant as a compliment to have someone call your voice “hard.”

If I was listening to my mother and my aunts or cousins speaking, and then chimed in, I would get the “shhhh” or if they wanted to be discreet they would make a gesture with their hands to indicate to me that I should bring my voice down. I learned early on that a lower voice was more appealing than the loud voice hiding in my vocal box.

I am Puerto Rican, and even though I was born in New York City, I was raised in a small town on the western side of Puerto Rico. I was already well-aware of stereotypes and digs about my being born in New York, even at a young age. My cousins would tell me I was stuck up, I thought I was better than other people because I had cable, I only listened to music in English (I guess that was a bad thing to them). When I moved to San Juan, I was no longer a displaced Nuyorican but a country bumpkin. Peers, friends, and new acquaintances would not classify me as a Nuyorican but, because I was living in San Juan at the time, would categorize me as an islander, de la isla, which basically meant I was not from el “area metro.” I was, in short, a country bumpkin to them.

The loudness of my voice was not just a marker of where I came from (the country, with all of the classicism that the phrase entails) but for me became conflated with gender. I knew that even when I wasn’t living in the city, I had been called loud. It’s just that when my peers asked me to lower my voice or to not speak so “duro” it was also because they thought of me as jíbara, country.

Sometimes I would get carried away when I was telling a joke among my female roommates, or I’d be excited to share some news, and eventually someone would tell me to tone it down. Baja la voz. As I reflect upon my college years living with roommates in a crowded apartment in a crowded city, I remember that we often got together and laughed, talked over each other, shouted across the apartment. But I would get carried away and then someone would say something about it. Mira que nos van a mandar a callar. Someone’s gonna tell us to shut up.

It was in college, however, that I learned to modulate my voice. I am physically capable of whispering, but when I spoke in English in a classroom setting (I was an English major in a school whose language of instruction was Spanish) I felt even louder in English. So I made the effort to tone down my voice, literally. I equated English with career, and by extension with my professional persona.

Ultimately, English would be the language I spoke (and still speak) in academic circles; with the language came also the tone and the volume. Men in my classes seemed more often to initiate conversations in my classes, and sometimes even in the ones where they were a minority. Meanwhile, the driven graduate student that I was, I wanted to step in but not stand out because of my voice. I didn’t want to give them (or the professor for that matter) a chance to discount me because I was a loud Puerto Rican woman at an American school. Eventually I learned how to switch back and forth. So did my fellow female classmates.

I remember as a teacher modulating my voice so I would be less loud and less abrasive in a college classroom. I wanted to assert my authority. If some women resort to vocal fry in order to be taken seriously, as this 2014 article in The Atlantic (online) suggests, I resorted to modulating my voice. That was my way of passing: passing for creative elite, passing for feminine, passing for authoritative. I tried to assert my credibility as a burgeoning scholar and professor by tweaking my voice. I laughed a little softer, I spoke a little slower, I sounded a little lower. I teetered between trying to sound feminine and trying to downplay my femininity through my voice.

Was I trying to sound more like the stereotype of a woman so I could be more credible in the classroom? Was this my own version of respectability politics? “Don’t be so loud and they’ll listen to you”?

“White supremacy grants white people the ability to be understood as expressing a dynamic range; whites can legitimately shout because we hear them/ourselves as mainly normalized. At the same time, white supremacy paints black people as always-already too loud.”

-Robin James, “Some philosophical implications of the “loudness war” and its criticisms”

The negative rhetoric about women and loudness is also connected to respectability politics. Take for example the stereotype of the angry black woman (which is in the vicinity of the loud Latina). If women must be delicate and feminine, being loud would be unattractive, unseemly. Loud also means “not being silent,” in other words, speaking when not spoken to. Robin James touches upon “loudness” in contemporary music, and how the turn toward less loud tracks also has to do with racialized ideas about who can speak and who can be loud–in other words, what counts as noise and what counts as harmonious sound. She cites Goldie Taylor’s piece in The Daily Beast about how, regardless of how angry she felt about the racial injustices in the United States, she would never be able to scream and shout without consequences. Loudness is something racialized people cannot afford.

The stereotype of the angry woman points to how the notion of who is loud and what tone of voice is considered loud are constructed. Although there are studies that point out that the sound of one’s voice indicates to others that one is in a position of authority or that one’s voice can make or break one’s career, there is yet to be a study that shows how the biology of the body that produces the voice affects what one can or cannot do. In other words, the connection between voice and our abilities, or our social class, is constructed—in our heads.

Assertive, aggressive, leader: these descriptions benefit men, for the most part. Aggressiveness is seen as a masculine trait, and along with that a loud tone of voice is also seen as masculine. (This idea is also problematic, for it sets anything that isn’t aggressive and assertive as female, and therefore negative.) The opposite applies to women; the same way our society associates fragile delicate things with femininity, a fragile, soft, low tone of voice is the acceptable range for a woman. And James and Taylor’s comments point to how race also changes the equation. Damned if we speak, damned if we don’t.

***

Over the years, I’ve become more comfortable with the way I sound. I’ve also become more comfortable switching between my aural codes, like I do with English, Spanish, and Spanglish. I know that there’s a volume that I use in certain spaces. I also know that in other spaces I don’t have to watch over how loud I am. If I am in a familiar space, with people I am close to, I feel less inclined to watch myself. I feel safe, not judged. I can be as loud as I want to be. But loudness is also an accepted way of speaking around my family. If I spoke in a low tone, I’d probably be picked on for that. My father, for one, has a booming, deep, loud voice, and so do many of my family members.

For me, embracing my voice is also a kind of body acceptance. My body, plus-sized and all, takes up space. My voice takes up space too. As a teenager and an adult I was constantly shamed for the way I look (skin too brown, voice too loud, face too painted, hair too short), and for a time tweaking my voice became a way to try to fit in. But I later learned how to respond to the remarks. I learned to be sarcastic. I learned to make jokes. I learned to talk back. I didn’t find my voice; I embraced my voice.

Dear readers, let us know in the comments: have you been chastised for being loud? Or for not speaking loudly enough?

—

Featured image: property of the author.

—

Liana M. Silva is co-founder and Managing Editor of Sounding Out!.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity–Regina Bradley

Learning to Listen Beyond Our Ears: Reflecting Upon World Listening Day—Owen Marshall

An Ear-splitting Cry: Gender, Performance, and Representations of Zaghareet in the U.S.–Meghan Drury

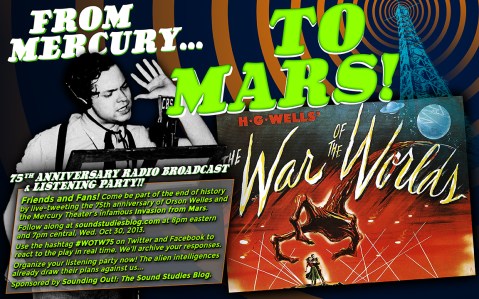

From Mercury to Mars: Jennifer Hyland Wang’s “After the Martians” from Antenna

“What I find so intriguing about the heated public discussion immediately following the War of the Worlds broadcast – in letters to the FCC and to Orson Welles, in newspaper pages, and in industry trade journals – is not just the way the controversy comments about the power of radio or the susceptibility of the audience, but the way in which the gendered logics embedded in the broadcast system rose to the surface in these debates and informed the popular, industrial, and regulatory discussions about the mass “hysteria” of October 30, 1938 …”

“What I find so intriguing about the heated public discussion immediately following the War of the Worlds broadcast – in letters to the FCC and to Orson Welles, in newspaper pages, and in industry trade journals – is not just the way the controversy comments about the power of radio or the susceptibility of the audience, but the way in which the gendered logics embedded in the broadcast system rose to the surface in these debates and informed the popular, industrial, and regulatory discussions about the mass “hysteria” of October 30, 1938 …”

[Reblogged from Antenna]

With Jennifer Hyland Wang‘s terrific exploration of the gendered logics surrounding the reception of the “War of the Worlds” broadcast and its implications for communications regulations, our six month series on the radio work of Orson Welles — From Mercury to Mars — comes to a close.

I have many supporters to thank for helping to bring this project together, but none so much as the Sounding Out! team – Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman, Liana Silva-Ford and Aaron Trammell, as well as our co-conspirators Nick Rubenstein and Monteith McCollum who contributed so much to the #WOTW75 project. Also a big thanks to Andrew Bottomley, my counterpart at Antenna and recruited all the authors from that end.

Chiefly, however, I want to thank all our writers for such smart and entertaining work. I think it’s fair to say that the Mercury to Mars project brought more insight into Welles’ radio years than virtually any other body of collected writing. In August, Cornell professor Tom McEnaney started out the series with a detailed study (here) of the role that Latin America played in Welles’ radio imagination and early film projects. Eleanor Patterson of the University of Wisconsin Madison followed up with her take on WOTW as a kind of residual radio (here). In the early Autumn, Professor Debra Rae Cohen of the University of South Carolina took on Welles’ first play in the Mercury cycle – his version of “Dracula” – explaining how it commented on the medium (here). On Antenna, Cynthia B. Meyers from the College of Mount Saint Vincent provided keen insight (here) on her experiences teaching WOTW in the classroom. Soon afterward, Kathleen Battles of Oakland University brought us her fascinating take (here) on Orson Welles’ self-parodies on the Fred Allen show and elsewhere, and in the lead-up to our #WOTW75 event, NYU’s Shawn VanCour made a compelling case (here) for why the second act of WOTW was so much more remarkable than the first.

Chiefly, however, I want to thank all our writers for such smart and entertaining work. I think it’s fair to say that the Mercury to Mars project brought more insight into Welles’ radio years than virtually any other body of collected writing. In August, Cornell professor Tom McEnaney started out the series with a detailed study (here) of the role that Latin America played in Welles’ radio imagination and early film projects. Eleanor Patterson of the University of Wisconsin Madison followed up with her take on WOTW as a kind of residual radio (here). In the early Autumn, Professor Debra Rae Cohen of the University of South Carolina took on Welles’ first play in the Mercury cycle – his version of “Dracula” – explaining how it commented on the medium (here). On Antenna, Cynthia B. Meyers from the College of Mount Saint Vincent provided keen insight (here) on her experiences teaching WOTW in the classroom. Soon afterward, Kathleen Battles of Oakland University brought us her fascinating take (here) on Orson Welles’ self-parodies on the Fred Allen show and elsewhere, and in the lead-up to our #WOTW75 event, NYU’s Shawn VanCour made a compelling case (here) for why the second act of WOTW was so much more remarkable than the first.

On the 75th anniversary of the “War of the Worlds” broadcast last October, we organized (or at least inspired) listening parties and collected hundreds of real-time tweets from participants in seven states and three countries all listening at the same time and using our hashtag #WOTW75. The exercise was coordinated with a three-hour SO!-produced broadcast from WHRW at SUNY Binghamton, with comments on the show by a dozen prominent scholars and writers, including Kate Lacey of Sussex University, Alex Russo of Catholic University, Brian Hanrahan of Cornell, John Cheng of SUNY Binghamton, Damian Keane of SUNY Buffalo, Jason Loviglio of the University of Maryland, Paul Heyer of Wilfrid Laurier University and more. We couldn’t be more proud of the depth of the material and the breadth of the event, which stretched from the University of Mississippi to Northwestern University, from Bournemouth University in the U.K. to the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto. Here is the navigator page we put up the night of the event, here is Aaron Trammell‘s remarkable audio documentary that aired early that night and here is Monteith McCollum‘s amazing WOTW “remix” that aired later.

On the 75th anniversary of the “War of the Worlds” broadcast last October, we organized (or at least inspired) listening parties and collected hundreds of real-time tweets from participants in seven states and three countries all listening at the same time and using our hashtag #WOTW75. The exercise was coordinated with a three-hour SO!-produced broadcast from WHRW at SUNY Binghamton, with comments on the show by a dozen prominent scholars and writers, including Kate Lacey of Sussex University, Alex Russo of Catholic University, Brian Hanrahan of Cornell, John Cheng of SUNY Binghamton, Damian Keane of SUNY Buffalo, Jason Loviglio of the University of Maryland, Paul Heyer of Wilfrid Laurier University and more. We couldn’t be more proud of the depth of the material and the breadth of the event, which stretched from the University of Mississippi to Northwestern University, from Bournemouth University in the U.K. to the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto. Here is the navigator page we put up the night of the event, here is Aaron Trammell‘s remarkable audio documentary that aired early that night and here is Monteith McCollum‘s amazing WOTW “remix” that aired later.

After the anniversary, our series continued to grow. Josh Shepperd of Catholic University reflected on what WOTW meant for the development of media studies (here) based on new archival research, and Jacob Smith of Northwestern wrote a terrific article (here) about “Hell on Ice,” Welles’ great drama of sailors lost in frozen wastes. We also commissioned new writing (here) on Welles’ adaptations of Sherlock Holmes by A. Brad Schwartz, who co-wrote a PBS program on the WOTW scandal. We also heard from two of the most prominent media studies scholars out there: Michele Hilmes of Madison wrote about the persistence and evolution of radio drama overseas after Welles (here), while Murray Pomerance of Ryerson University wrote a rich and provocative study (here) of Welles’ voice itself.

Thanks to one and all. For my part, it’s simply been a joy to share my boundless fascination with Orson Welles’s radio work with so many friends, fans and colleagues. Signing out now, on behalf of Mercury to Mars, I remain your obedient servant, Neil Verma.

Recent Comments