The Sounds of Writing and Learning

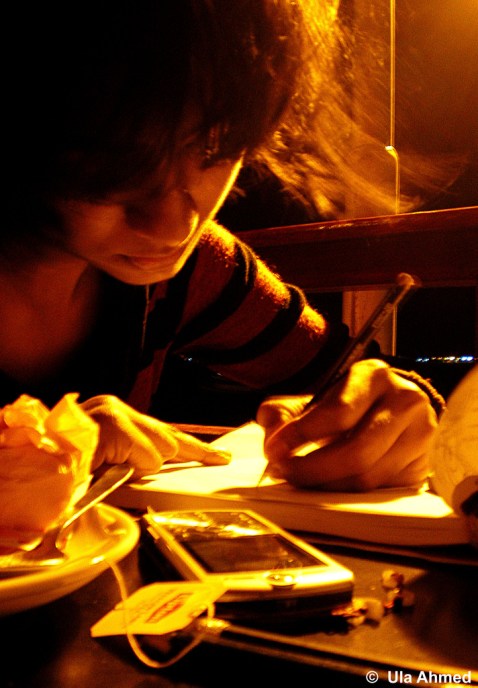

“I Rise,” image by Flickr User Lua Ahmed

Welcome back to Sounding Out!‘s fall forum on “Sound and Pedagogy.” Developed to explore the relationship between sound and learning, this forum blends the thinking of our editors (Liana Silva), recruited guests (D. Travers Scott), and one of the winners of our recent Call For Posts (Jentery Sayers) to explore how listening impacts the writing process, the teachable moment, and the syllabus (and vice versa). Sharpen your pencils and/or give your typing fingers a good stretch, because today’s offering from Liana Silva asks you to exercise unexpected writing muscles—your tongue, mouth, and vocal chords! If you need a make-up assignment for last week’s post by D. Travers Scott, “Listening to #Occupy in the Classroom,” click here. And don’t forget–same class time next week!–JSA, Editor in Chief

Welcome back to Sounding Out!‘s fall forum on “Sound and Pedagogy.” Developed to explore the relationship between sound and learning, this forum blends the thinking of our editors (Liana Silva), recruited guests (D. Travers Scott), and one of the winners of our recent Call For Posts (Jentery Sayers) to explore how listening impacts the writing process, the teachable moment, and the syllabus (and vice versa). Sharpen your pencils and/or give your typing fingers a good stretch, because today’s offering from Liana Silva asks you to exercise unexpected writing muscles—your tongue, mouth, and vocal chords! If you need a make-up assignment for last week’s post by D. Travers Scott, “Listening to #Occupy in the Classroom,” click here. And don’t forget–same class time next week!–JSA, Editor in Chief

—

When I started this draft, I sat in an office that is not mine, next to an old, whirring Westclox Dialite electric clock. When I write, I usually pop my headphones on and blast my “Writing” playlist on my iPhone. But that day, I was soothed by the sounds of a whirring clock and the air blasting through a wall vent. On another day I worked on my draft while I listened to sports talk radio, a big part of my morning routine; toward the end of the drafting process I shared this blog post with a writing consultant at the writing center where I work.

For me, writing is always connected to sound. Sound inhabits the spaces where I write, either in the shape of music, typing, or voices. These sounds are never far from my writing process. In fact, something so small as the typing of the keys as I write this can be construed as the soundtrack to my writing. Sounding Out! guest blogger and author Bridget Hoida made a case for how sound is part of the texts she reads and how she weaves sound into her own writing; in my case, I can’t think of writing without sound. It is my soundtrack/sound track, in the sense that sound is the track on which I lay my writing process, like the lines of a ruled notebook.

However, many writers and educators tend to think of writing as a solitary, lonely, quiet endeavor. Last month, at an orientation where I was speaking, I heard someone refer to the “quiet activity of writing and learning.” As I looked around me, stunned, I seemed to be the only one surprised at this assertion. Although it is a common perception, as a writer, ex-writing instructor, and writing center staff member, this did not make sense to me. Both writing and learning, for me, are connected to sound, whether it was listening to music while editing or talking through my ideas during class discussion. If, to paraphrase Brandon Labelle in Acoustic Territories, places configure what sounds are deemed acceptable and unacceptable, do schools configure what are the appropriate sounds of learning?

I approach this question about the sounds of learning from the angle of my work at the writing center. For years I taught first-year composition, and later on in my academic career I started working at a writing center (where I currently work). At the Writing Center we are surrounded by the sounds of writing and learning. A student will walk up to one of our locations and meet with a writing consultant. They will discuss the writer’s text, in the case that the writer brings a draft. After this discussion, the consultant will read the writer’s text aloud, a practice that all of our writing consultants must adhere to. The text comes alive in the voice of the consultant; the good, the bad, and the ugly are made audible, concrete in the voice of the consultant. This enables both parties to hear the paper, but also to listen to the paper and, ideally, understand it better. The consultant and the writer then talk about what works, what doesn’t, what could be improved and how. Learning takes place through a conversation. It is at the writing center where writing and learning processes are no longer silent, but actually audible. The value for a writer of hearing their text aloud is not new; in 1967, Anthony Tovatt and Ebert L. Miller did a three-year study on how listening to their writing helped high-school writers improve their writing skills (see their article “The Sound of Writing”). My concern is how learning is coded as silent, despite evidence to the contrary.

I wonder about the implications of describing learning and writing as “silent” processes. Silence already has a domesticating quality: it is portrayed as the gift of the restrainted, of the eloquent, of the elite, and these ideas about silence and noise emerge from 19th Century ideas about respectability and middle-class values. As an example, American Studies scholar Daniel Cavicchi states in Listening and Longing: Music Lovers in the Age of Barnum,

“In fact, both in the North and the South, genteel people came to value the quietude of silent reading and listening as a form of ‘productive leisure’ that was explicitly opposed to the louder, more boisterous pastimes of slaves, immigrants, and workers. As in the days when European colonists and Native Americans struggled to understand each other’s sound worlds, aural difference now became a wedge that allowed those in power to place certain groups figuratively and literally outside the bounds of civilization” (52).

Ideas of learning as silent are coded in broader discourse about silence (or, to use Cavicchi’s more accurate terminology, quietude) and noise, about what is respectable and what is not. How do these common connotations of quietude as dignified and sound/noise as unpleasant carry over to descriptions of of learning? It is possible that society has normalized these types of learning (the “silent” types) as of a higher caliber, and schools have a major part in that: reading to one’s self in silence, filling out exam questions and not talking to anyone, typing in a quiet library at a computer station fit for only one. Even a lecture dignifies silence, in a way: students sit down and listen to what the teacher/professor has to say while they digest, quietly, what is being taught. In opposition, the sounds of learning can be associated to the sounds of collaboration, as it were: tutorials, consultations, advising sessions, discussion sections, movie viewings. Although talking is not the only way to collaborate in order to learn, I posit that these learning activities that are usually non-silent fall prey to hierarchies of sound and silence.

“Student Writing 2002,” Image by Flickr user Cybrarian

These hierarchies of sound and silence tell listeners that the learning activities that are portrayed as silent are more legitimate than those that are portrayed as boisterous, loud, animated—in other words, activities producing sound. In fact, it doesn’t have to be either/or. The fact that they are set in opposition to themselves is in itself problematic. Isolating sound from the learning process acts as a way of emphasizing writing as the main component of learning. Jody Shipka in “Sound Engineering: Toward a Theory of Multimodal Soundness” describes how writing is thought of as “the communication of scholarly, rigorous arguments or ideas, something more often associated with the production of linear, print-based texts” (356, emphasis in original). This dichotomy of rigor versus play can be portrayed also as visuality (as embodied in the written text) versus aurality. The writing center can be the place where these ideas are tested, in the sense that it is a location of collaborative learning where some learn by writing and others benefit from talk while others benefit from listening. By privileging quietude and solitude as the ideal modes for learning, we miss out on other important vehicles for learning, such as sound.

***

If I started this post with the whirring of the Westclox clock, how did I end this post? I ended it on a busy Sunday evening, while my daughter slept and my boyfriend talked on the phone. I finished it with the chatter of the air conditioner, the clack of baseballs against bats coming from the living room, and the click click click of the keyboard keeping me company.

—

Liana M. Silva is co-founder and Managing Editor of Sounding Out!

Share this:

Listening to #Occupy in the Classroom

Yes, it’s that time again, readers. You are going to have to stop pretending the “Back to School” aisles haven’t been appearing in stores for the past few weeks. We at SO! are here to ease your transition from summer work schedules to the business of teaching and student-ing with our fall forum on “Sound and Pedagogy.” Developed to explore the relationship between sound and learning, this forum blends the thinking of our editors (Liana Silva), recruited guests (D. Travers Scott), and one of the winners of our recent Call For Posts (Jentery Sayers) to explore how listening impacts the writing process, the teachable moment, and the syllabus (and vice versa). We hope to inspire your fall planning–whether or not you teach a course on “sound studies”–and encourage teachers and students of any subjects to reconsider the classroom as a sensory space. We also encourage you to share your feedback, tips, and experiences in comments to these posts and on our Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit sites. As I said in the Call for Posts for this Forum: “because teaching is so crucial—yet so frequently ignored at conferences and on campus—Sounding Out! wants to wants to provide a virtual space for this vital discussion.” This conversation will be ongoing: we will also bring you a “Spring Break Brush-Up” edition in 2013 featuring several more excellent posts by writers selected from our open call. Right now, the bell’s about to ring–so take a seat, open those ears, and enjoy this shiny auditory apple of an offering from D. Travers Scott in which he discusses how the sounds of #Occupy invigorated his classroom. And, yes, it will be on the test. —JSA, Editor-in-Chief

Yes, it’s that time again, readers. You are going to have to stop pretending the “Back to School” aisles haven’t been appearing in stores for the past few weeks. We at SO! are here to ease your transition from summer work schedules to the business of teaching and student-ing with our fall forum on “Sound and Pedagogy.” Developed to explore the relationship between sound and learning, this forum blends the thinking of our editors (Liana Silva), recruited guests (D. Travers Scott), and one of the winners of our recent Call For Posts (Jentery Sayers) to explore how listening impacts the writing process, the teachable moment, and the syllabus (and vice versa). We hope to inspire your fall planning–whether or not you teach a course on “sound studies”–and encourage teachers and students of any subjects to reconsider the classroom as a sensory space. We also encourage you to share your feedback, tips, and experiences in comments to these posts and on our Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit sites. As I said in the Call for Posts for this Forum: “because teaching is so crucial—yet so frequently ignored at conferences and on campus—Sounding Out! wants to wants to provide a virtual space for this vital discussion.” This conversation will be ongoing: we will also bring you a “Spring Break Brush-Up” edition in 2013 featuring several more excellent posts by writers selected from our open call. Right now, the bell’s about to ring–so take a seat, open those ears, and enjoy this shiny auditory apple of an offering from D. Travers Scott in which he discusses how the sounds of #Occupy invigorated his classroom. And, yes, it will be on the test. —JSA, Editor-in-Chief

—

In the late fall of 2011, I was teaching a class on cultural studies of advertising. I presented the Occupy Student Debt campaign, a subcategory or spinoff of the larger Occupy movement, while we were examining ways people challenged consumer culture. We discussed education as a commodity and students as consumers. Unsurprisingly, my seniors were dissatisfied consumers. They expressed that what had been advertised to them was a product that guaranteed or at least would strongly increase their chances for quality employment (of course, it was also a product they had worked for years in creating, and one they couldn’t return.) If higher education really did land you the lucrative job it had been advertised as guaranteeing, in theory, then, you would be able to more easily pay off student loan debt. To address this dissatisfaction, I showed them two artifacts: a video from the launch in New York City on November 12, 2011, and the OSD debtors’ pledge*.

In the video, OSD founder Pamela Brown reads the pledge one line at a time, with each line chanted back by others. I played the video in a dark classroom. I also projected it on the room’s main screen, but I didn’t use the room’s amplification system because it sounds too much like an authoritarian public address and disperses the audio in a dominating way. External speakers connected to my laptop made the sound feel, to me, more localized and objectified, something we could focus on rather than an institutional part of the room. The students’ first reaction was, not to the words, but the sound: the verbal relay used at the public demonstration. Brows furrowed and heads cocked quizzically, they asked, “Why are they all repeating the speaker like that?” I explained how this provides additional amplification, but the students’ listening experience was instructive to me. Their unfamiliarity with a sonic practice of vocalization indicated their unfamiliarity with larger practices of collective, public social action.

Listening to OSD, and paying attention to how my students listened to it, informed me of larger contexts they needed to understand and discuss it, in ways that the object of the text did not suggest to me. It made me think about the experience and process of my students’ encountering OSD. I immediately noticed its ambient sounds of city life, which I no longer hear. These sounds of traffic, the acoustics of being surrounded by buildings, etc. gave several urban dimensions to the movement the pledge text did not. From the perspective of Upstate South Carolina, “urban” is not a simple thing, an identity or geography category, but intersectional: our largest city, Greenville, has a population under 60,000. City noises feel not merely urban, but un-Southern, and thereby alien. (I say un-Southern rather than Northern or Yankee because another thing I’ve learned here is the inadequacy of that binary: Los Angeles, for example, is not a Northern city but most certainly is as un-Southern as New York. Cities also carry a class dimension.) Even though my school is one of the elite institutions in this area, this region is still worse off economically than the rest of the country and has a generally lower cost of living. Cities require money to live in. In spatial, class, and urban dimensions, OSD felt alien.

Opening of the Occupy Student Debt Campaign, Image by Flickr User JohannaClear

The experience of listening to the ODS rally illustrates how a sound studies perspective foregrounds experiential processes over exclusive categories of things and ideas. For example, when I read the OSD Debtors’ Pledge aloud to my students—vocalizing the text and sounds and listening to them— it brought the text into my body, making it an action. It also made students uncomfortable. Even just a round-robin reading of theory seems to make then anxious and fidgety. While I try to understand and accommodate anxieties around public speaking, I think the way sound makes a text enter the body can be a powerful affective experience. And no one ever said the classroom always had to be comfortable. For me, reading the text aloud personalized the OSD pledge. It evoked sensory memories: “Pledge of” evoked saying the pledge of allegiance in public school; saying “We believe” took me to attending Lutheran church services with my husband at the time where they collectively recite the Apostles’ Creed. These associations evoked emotional disidentifications from organized religion and mandatory collective professions of patriotism. It also temporalized and spatialized OSD for me, positioning it in relations to Dallas, Texas in the 1970s and Greenville, SC today.

Overall, the reading aloud of the pledge staged a tension or dialectic of identification and disidentifications. Although I agreed and identified with the sentiments of the movement, several alienating and unsettling aspects of the pledge came through as I read aloud: the blithe collapsings of “we” and “as members of the most indebted generations” made me wary (collectives always do, but so do easy historical assertions. Really? Are we more indebted than indentured servants who came to America, or people born into slavery?), and the sudden shift to first person singular at the very end seemed jarring: (After saying “we” six times, suddenly it’s ‘I’ now – what happened?). Lastly, the numerous alliterations also had an alienating effect, making the text seem sophistic and manipulative, artificial, composed.

The auditory experience of OSD can also provide insight into how we create texts. A video of Andrew Ross shows him presenting the first, “very rough draft” weeks earlier at an OWS event. Listening to him read this different, earlier version underscores the text as process. The pledge is something that developed. While his flat tone and straight male voice do not appeal to me, they do complexify and dimensionalize Brown’s reading, giving it depth. They also show that some things that bothered me in the final version – the collectivity and alliterations – were not there. This intertextual, diachronic listening does not erase troublesome aspects of the ‘final’ text, but it mediates them. I am moved closer to it by listening to its different origin.

Arguably, any of these points could have been arrived at by good ole’ textual analysis. My point is not that listening always should supplant visual modes; sound studies tries to break that false dichotomy by not denigrating or replacing the visual but by elevating the sonic to complementary – not superseding – status. I argue that reading aloud should be a fundamental, basic component of sound studies methodology, as it allows anyone to hear, voice, embody, and experience a text. I not only noticed these aspects sooner through listening – my first time speaking it aloud, despite having read it at least a dozen times before. Moreover, I didn’t just notice them: I felt them on a personal, emotional, level, which spurs thinking and analysis that is, if not completely new and unique, definitely qualitatively different in its potency and urgency.

Listening to OWS, and the OSD in particular, brings insights affective and personal. Yes, I can read a statistic from a survey stating that a certain percentage of participants in OWS feel angry or betrayed. That doesn’t mean anything to me in a specific, personal, and empathetic way – and empathy is crucial for a social movement to garner support. Listening to both Ross and Brown, I am reflective and conflicted over my professional role – no longer a grad student, but certainly not an established scholar like Ross. I feel connected to OSD in ways beyond the literal facts of my debt. Listening draws me into a contemplative, reflexive space beyond a sticky note on my office desk saying “OWS: teachable moment.” I can see a map with big, red OWS circles over Washington D.C. and New York, but I don’t feel the distance from myself and my students in the same way—and this is crucial for my teaching and engaging them in dialogue about what could be the most significant social movements of their lifetimes.

Share this:

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Rhetoric After Sound: Stories of Encountering “The Hum” Phenomenon

- Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions

- Wingsong: Restricting Sound Access to Spotted Owl Recordings

- Listening Together/Apart: Intimacy and Affective World-Building in Pandemic Digital Archival Sound Projects

- The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments