Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series for Sounding Out! (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It starts today, with Amina Abbas-Nazari, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice– are we training it, or is it actually training us?

—

Hi, good morning. I’m calling in from Bangalore, India.” I’m talking on speakerphone to a man with an obvious Indian accent. He pauses. “Now I have enabled the accent translation,” he says. It’s the same person, but he sounds completely different: loud and slightly nasal, impossible to distinguish from the accents of my friends in Brooklyn.

The AI startup erasing call center worker accents: is it fighting bias – or perpetuating it? (Wilfred Chan, 24 August 2022)

This telephone interaction was recounted in The Guardian reporting on a Silicon Valley tech start-up called Sanas. The company provides AI enabled technology for real-time voice modification for call centre workers voices to sound more “Western”. The company describes this venture as a solution to improve communication between typically American callers and call centre workers, who might be based in countries such as Philippines and India. Meanwhile, research has found that major companies’ AI interactive speech systems exhibit considerable racial imbalance when trying to recognise Black voices compared to white speakers. As a result, in the hopes of being better heard and understood, Google smart speaker users with regional or ethnic American accents relay that they find themselves contorting their mouths to imitate Midwestern American accents.

These instances describe racial biases present in voice interactions with AI enabled and mediated communication systems, whereby sounding ‘Western’ entitles one to more efficient communication, better usability, or increased access to services. This is not a problem specific to AI though. Linguistics researcher John Baugh, writing in 2002, describes how linguistic profiling is known to have resulted in housing being denied to people of colour in the US via telephone interactions. Jennifer Stoever‘s The Sonic Color Line (2016) presents a cultural and political history of the racialized body and how it both informed and was informed by emergent sound technologies. AI mediated communication repeats and reinforces biases that pre-exist the technology itself, but also helping it become even more widely pervasive.

Mozilla’s commendable Common Voice project aims to ‘teach machines how real people speak’ by building an open source, multi-language dataset of voices to improve usability for non-Western speaking or sounding voices. But singer and musicologist, Nina Sun Eidsheim describes how ’a specific voice’s sonic potentiality [in] its execution can exceed imagination’ (7), and voices as having ‘an infinity of unrealised manifestations’ (8) in The Race of Sound (2019). Eidsheim’s sentiments describe a vocal potential, through musicality, that exists beyond ideas of accents and dialects, and vocal markers of categorised identity. As a practicing vocal performer, I recognise and resonate with Eidsheim’s ideas I have a particular interest in extended and experimental vocality, especially gained through my time singing with Musarc Choir and working with artist Fani Parali. In these instances, I have experienced the pleasurable challenge of being asked to vocalise the mythical, animal, imagined, alien and otherworldly edges of the sonic sphere, to explore complex relations between bodies, ecologies, space and time, illuminated through vocal expression.

Following from Eidsheim, and through my own vocal practice, I believe AI’s prerequisite of voices as “fixed, extractable, and measurable ‘sound object[s]’ located within the body” is over-simplistic and reductive. Voices, within systems of AI, are made to seem only as computable delineations of person, personality and identity, constrained to standardised stereotypes. By highlighting vocal potential, I offer a unique critique of the way voices are currently comprehended in AI recognition systems. When we appreciate the voice beyond the homogenous, we give it authority and autonomy, ultimately leading to a fuller understanding of the voice and its sounding capabilities.

My current PhD research, Speculative Voicing, applies thinking about the voice from a musical perspective to the sound and sounding of voices in artificially intelligent conversational systems. Herby the voice becomes an instrument of the body to explore its sonic materiality, vocal potential and extremities of expression, rather than being comprehended in conjunction to vocal markers of identity aligning to categories of race, gender, age, etc. In turn, this opens space for the voice to be understood as a shapeshifting, morphing and malleable entity, with immense sounding potential beyond what might be considered ordinary or everyday speech. Over the long term this provides discussion of how experimenting with vocal potential may illuminate more diverse perspectives about our sense of self and being in relation to vocal sounding.

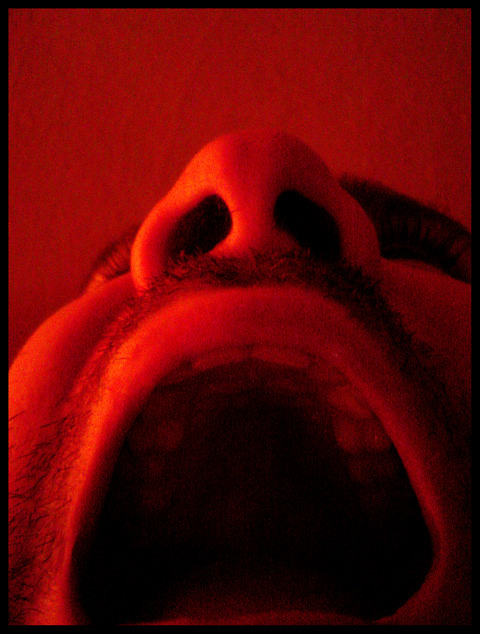

Vocal and movement artist Elaine Mitchener exhibits the disillusion of the voice as ‘fixed’ perfectly in her performance of Christian Marclay’s No!, which I attended one hot summer’s evening at the London Contemporary Music Festival in 2022. Marclay’s graphic score uses cut outs from comic book strips to direct the performer to vocalise a myriad of ‘No”s.

Mitchener’s rendering of the piece involved the cooperation and coordination of her entire body, carefully crafting lips, teeth, tongue, muscles and ligaments to construct each iteration of ‘No.’ Each transmutation of Mitchener’s ‘No’s’ came with a distinct meaning, context, and significance, contained within the vocalisation of this one simple syllable. Every utterance explored a new vocal potential, enabled by her body alone. In the context of AI mediated communication, we can see this way of working with the voice renders the idea of the voice as ‘fixed’ as redundant. Mitchener’s vocal potential demonstrates that voices can and do exist beyond AI’s prescribed comprehension of vocal sounding.

In order to further understand how AI transcribes understandings of voice onto notions of identity, and vocal potential, I produced the practice project Polyphonic Embodiment(s) as part of my PhD research, in collaboration with Nestor Pestana, with AI development by Sitraka Rakotoniaina. The AI we created for this project is based upon a speech-to-face recognition AI that aims to be able to tell what your face looks like from the sound of your voice. The prospective impact of this AI is deeply unsettling, as its intended applications are wide-ranging – from entertainment to security, and as previously described AI recognition systems are inherently biased.

This multi-modal form of comprehending voice is also a hot topic of research being conducted by major research institutions including Oxford University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. We wanted to explore this AI recognition programme in conjunction with an understanding of vocal potential and the voice as a sonic material shaped by the body. As the project title suggests, the work invites people to consider the multi-dimensional nature of voice and vocal identity from an embodied standpoint. Additionally, it calls for contemplation of the relationships between voice and identity, and individuals having multiple or evolving versions of identity. The collaboration with the custom-made AI software creates a feedback loop to reflect on how peoples’ vocal sounding is “seen” by AI, to contest the way voices are currently heard, comprehended and utilised by AI, and indeed the AI industry.

The video documentation for this project shows ‘facial’ images produced by the voice-to-face recognition AI, when activated by my voice, modified with simple DIY voice devices. Each new voice variation, created by each device, produces a different outputted face image. Some images perhaps resemble my face? (e.g. Device #8) some might be considered more masculine? (e.g. Device #10) and some are just disconcerting (e.g. Device #4). The speculative nature of Polyphonic Embodiment(s) is not to suggest that people should modify their voices in interaction with AI communication systems. Rather the simple devices work with bodily architecture and exaggerate its materiality, considering it as a flexible instrument to explore vocal potential. In turn this sheds light on the normative assumptions contained within AI’s readings of voice and its relationships to facial image and identity construction.

Through this artistic, practice-led research I hope to evolve and augment discussion around how the sounding of voices is comprehended by different disciplines of research. Taking a standpoint from music and design practice, I believe this can contest ways of working in the realms of AI mediated communication and shape the ways we understand notions of (vocal) identity: as complex, fluid, malleable, and ultimately not reducible to Western logics of sounding.

—

Featured Image: Still image from Polyphonic Embodiments, courtesy of author.

—

Amina Abbas-Nazari is a practicing speculative designer, researcher, and vocal performer. Amina has researched the voice in conjunction with emerging technology, through practice, since 2008 and is now completing a PhD in the School of Communication at the Royal College of Art, focusing on the sound and sounding of voices in artificially intelligent conversational systems. She has presented her work at the London Design Festival, Design Museum, Barbican Centre, V&A, Milan Furniture Fair, Venice Architecture Biennial, Critical Media Lab, Switzerland, Litost Gallery, Prague and Harvard University, America. She has performed internationally with choirs and regularly collaborates with artists as an experimental vocalist

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

What is a Voice?–Alexis Deighton MacIntyre

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–-Steph Ceraso

Mr. and Mrs. Talking Machine: The Euphonia, the Phonograph, and the Gendering of Nineteenth Century Mechanical Speech – J. Martin Vest

One Scream is All it Takes: Voice Activated Personal Safety, Audio Surveillance, and Gender Violence—María Edurne Zuazu

Echo and the Chorus of Female Machines—AO Roberts

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice– Yvon Bonefant

Can’t Nobody Tell Me Nothin: Respectability and The Produced Voice in Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road”

It’s been ten weeks now that we’ve all been kicking back in our Wranglers. allowing Lil Nas X’s infectious twang in “Old Town Road” to shower us in yeehaw goodness from its perch atop the Billboard Hot 100. Entrenched as it is on the pop chart, though, “Old Town Road”’s relationship to Billboard got off to a shaky start, first landing on the Hot Country Songs list only to be removed when the publication determined the hit “does not embrace enough elements of today’s country music to chart in its current version.” There’s a lot to unpack in a statement like that, and folks have been unpacking it quite consistently, especially in relation to notions of genre and race (in addition to Matthew Morrison’s recommended reads, I’d add Karl Hagstrom-Miller’s Segregating Sound, which traces the roots of segregated music markets). Using the context of that ongoing discussion about genre and race, I’m listening here to a specific moment in “Old Town Road”— the line “can’t nobody tell me nothin”—and the way it changes from the original version to the Billy Ray Cyrus remix. Lil Nas X uses the sound of his voice in this moment to savvily leverage his collaboration with a country music icon, and by doing so subtly drawing out the respectability politics underlying Billboard’s racialized genre categorization of his song.

After each of Lil Nas X’s two verses in the original “Old Town Road,” we hear the refrain “can’t nobody tell me nothin.” The song’s texture is fairly sparse throughout, but the refrains feature some added elements. The 808-style kick drum and rattling hihats continue to dominate the soundscape, but they yield just enough room for the banjo sample to come through more clearly than in the verse, and it plucks out a double-time rhythm in the refrain. The vocals change, too, as Lil Nas X performs a call-and-response with himself. The call, “can’t nobody tell me nothin,” is center channel, just as his voice has been throughout the verse, but the response, “can’t tell me nothin,” moves into the left and right speaker, a chorus of Lil Nas X answering the call. Listen closely to these vocals, and you’ll also hear some pitch correction. Colloquially known as “autotune,” this is an effect purposely pushed to extreme limits to produce garbled or robotic vocals and is a technique most often associated with contemporary hip hop and R&B. Here, it’s applied to this melodic refrain, most noticeably on “nothin” in the call and “can’t” in the response,

After Billboard removed the song from the Hot Country chart in late March, country star Billy Ray Cyrus tweeted his support for “Old Town Road,” and by early April, Lil Nas X had pulled him onto the remix that would come to dominate the Hot 100. The Cyrus remix is straightforward: Cyrus takes the opening chorus, then Lil Nas X’s original version plays through from the first verse to the last chorus, at which point Cyrus tacks on one more verse and then sings the hook in tandem with Lil Nas X to close the song. Well, it’s straightforward except that, while Lil Nas X’s material sounds otherwise unaltered from the original version, the pitch correction is smoothed out so that the garble from the previous version is gone.

In order to figure out what happened to the pitch correction from the first to second “Old Town Road,” I’m bringing in a conceptual framework I’ve been tinkering with the last couple of years: the produced voice. Within this framework, all recorded voices are produced in two specific ways: 1) everyone performs their bodies in relation to gender, race, ability, sex, and class norms, and 2) everyone who sings on record has their voice altered or affected with various levels of technology. To think about a produced voice is to think about how voices are shaped by recording technologies and social technologies at the same time. Listening to the multiple versions of “Old Town Road” draws my attention specifically to the always collaborative nature of produced voices.

In performativity terms—and here Judith Butler’s idea in “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory” that “one is not simply a body, but, in some very key sense, one does one’s body” (521) is crucial—a collaboratively produced voice is a little nebulous, as it’s not always clear who I’m collaborating with to produce my voice. Sometimes I can (shamefully, I assure you) recognize myself changing the way my voice sounds to fit into some sort of, say, gendered norm that my surroundings expect. As a white man operating in a white supremacist, cisheteropatriarchal society, the deeper my voice sounds, the more authority adheres to me. (Well, only to a point, but that’s another essay). Whether I consciously or subconsciously make my voice deeper, I am definitely involved in a collaboration, as the frequency of my voice is initiated in my body but dictated outside my body. Who I’m collaborating with is harder to establish – maybe it’s the people in the room, or maybe my produced voice and your listening ears (read Jennifer Stoever’s The Sonic Color Line for more on the listening ear) are all working in collaboration with notions of white masculine authority that have long-since been baked into society by teams of chefs whose names we didn’t record.

In studio production terms, a voice’s collaborators are often hard to name, too, but for different reasons. For most major label releases, we could ask who applied the effects that shaped the solo artist’s voice, and while there’s a specific answer to that question, I’m willing to bet that very few people know for sure. Even where we can track down the engineers, producers, and mix and master artists who worked on any given song, the division of labor is such that probably multiple people (some who aren’t credited anywhere as having worked on the song) adjusted the settings of those vocal effects at some point in the process, masking the details of the collaboration. In the end, we attribute the voice to a singular recording artist because that’s the person who initiated the sound and because the voice circulates in an individualistic, capitalist economy that requires a focal point for our consumption. But my point here is that collaboratively produced voices are messy, with so many actors—social or technological—playing a role in the final outcome that we lose track of all the moving pieces.

Not everyone is comfortable with this mess. For instance, a few years ago long-time David Bowie producer Tony Visconti, while lamenting the role of technology in contemporary studio recordings, mentioned Adele as a singer whose voice may not be as great as it is made to sound on record. Adele responded by requesting that Visconti suck her dick. And though the two seemed at odds with each other, they were being equally disingenuous: Visconti knows that every voice he’s produced has been manipulated in some way, and Adele, too, knows that her voice is run through a variety of effects and algorithms that make her sound as epically Adele as possible. Visconti and Adele align in their desire to sidestep the fundamental collaboration at play in recorded voices, keeping invisible the social and political norms that act on the voice, keeping inaudible the many technologies that shape the voice.

Propping up this Adele-Visconti exchange is a broader relationship between those who benefit from social gender/race scripts and those who benefit from masking technological collaboration. That is, Adele and Visconti both benefit, to varying degrees, from their white femininity and white masculinity, respectively; they fit the molds of race and gender respectability. Similarly, they both benefit from discourses surrounding respectable music and voice performance; they are imbued with singular talent by those discourses. And on the flipside of that relationship, where we find artists who have cultivated a failure to comport with the standards of a respectable singing voice, we’ll also find artists whose bodies don’t benefit from social gender/race scripts: especially Black and Brown artists—non-binary, women, and men. Here I’m using “failure” in the same sense Jack Halberstam does in The Queer Art of Failure, where failing is purposeful, subversive. To fail queerly isn’t to fall short of a standard you’re trying to meet; it’s to fall short of a standard you think is bullshit to begin with. This kind of failure would be a performance of non-conformity that draws attention to the ways that systemic flaws – whether in social codes or technological music collaborations – privilege ways of being and sounding that conform with white feminine and white masculine aesthetic standards. To fail to meet those standards is to call the standards into question.

So, because respectably collaborating a voice into existence involves masking the collaboration, failing to collaborate a voice into existence would involve exposing the process. This would open up the opportunity for us to hear a singer like Ma$e, who always sings and never sings well, as highlighting a part of the collaborative vocal process (namely pitch correction, either through training or processing the voice) by leaving it out. To listen to Ma$e in terms of failed collaboration is to notice which collaborators didn’t do their work. In Princess Nokia’s doubled and tripled and quadrupled voice, spread carefully across the stereo field, we hear a fully exposed collaboration that fails to even attempt to meet any standards of respectable singing voices. In the case of the countless trap artists whose voices come out garbled through the purposeful misapplication of pitch correction algorithms, we can hear the failure of collaboration in the clumsy or over-eager use of the technology. This performed pitch correction failure is the sound I started with, Lil Nas X on the original lines “can’t nobody tell me nothin.” It’s one of the few times we can hear a trap aesthetic in “Old Town Road,” outside of its instrumental.

In each of these instances, the failure to collaborate results in the failure to achieve a respectably produced voice: a voice that can sing on pitch, a voice that can sing on pitch live, a voice that is trained, a voice that is controlled, a voice that requires no intervention to be perceived as “good” or “beautiful” or “capable.” And when respectable vocal collaboration further empowers white femininity or white masculinity, failure to collaborate right can mean failing in a system that was never going to let you pass in the first place. Or failing in a system that applies nebulous genre standards that happen to keep a song fronted by a Black artist off the country charts but allow a remix of the same song to place a white country artist on the hip hop charts.

The production shift on “can’t nobody tell me nothin” is subtle, but it brings the relationship between social race/gender scripts and technological musical collaboration into focus a bit. It isn’t hard to read “does not embrace enough elements of today’s country music” as “sounds too Black,” and enough people called bullshit on Billboard that the publication has had to explicitly deny that their decision had anything to do with race. Lil Nas X’s remix with Billy Ray Cyrus puts Billboard in a really tricky rhetorical position, though. Cyrus’s vocals—more pinched and nasally than Lil Nas X’s, with more vibrato on the hook (especially on “road” and “ride”), and framed without the hip hop-style drums for the first half of his verse—draw attention to the country elements already at play in the song and remove a good deal of doubt about whether “Old Town Road” broadly comports with the genre. But for Billboard to place the song back on the Country chart only after white Billy Ray Cyrus joined the show? Doing so would only intensify the belief that Billboard’s original decision was racially motivated. In order for Billboard to maintain its own colorblind respectability in this matter, in order to keep their name from being at the center of a controversy about race and genre, in order to avoid being the publication believed to still be divvying up genres primarily based on race in 2019, Billboard’s best move is to not move. Even when everyone else in the world knows “Old Town Road” is, among other things, a country song, Billboard’s country charts will chug along as if in a parallel universe where the song never existed.

The production shift on “can’t nobody tell me nothin” is subtle, but it brings the relationship between social race/gender scripts and technological musical collaboration into focus a bit. It isn’t hard to read “does not embrace enough elements of today’s country music” as “sounds too Black,” and enough people called bullshit on Billboard that the publication has had to explicitly deny that their decision had anything to do with race. Lil Nas X’s remix with Billy Ray Cyrus puts Billboard in a really tricky rhetorical position, though. Cyrus’s vocals—more pinched and nasally than Lil Nas X’s, with more vibrato on the hook (especially on “road” and “ride”), and framed without the hip hop-style drums for the first half of his verse—draw attention to the country elements already at play in the song and remove a good deal of doubt about whether “Old Town Road” broadly comports with the genre. But for Billboard to place the song back on the Country chart only after white Billy Ray Cyrus joined the show? Doing so would only intensify the belief that Billboard’s original decision was racially motivated. In order for Billboard to maintain its own colorblind respectability in this matter, in order to keep their name from being at the center of a controversy about race and genre, in order to avoid being the publication believed to still be divvying up genres primarily based on race in 2019, Billboard’s best move is to not move. Even when everyone else in the world knows “Old Town Road” is, among other things, a country song, Billboard’s country charts will chug along as if in a parallel universe where the song never existed.

As Lil Nas X shifted Billboard into a rhetorical checkmate with the release of the Billy Ray Cyrus remix, he also shifted his voice into a more respectable rendition of “can’t nobody tell me nothin,” removing the extreme application of pitch correction effects. This seems the opposite of what we might expect. The Billy Ray Cyrus remix is defiant, thumbing its nose at Billboard for not recognizing the countryness of the tune to begin with. Why, in a defiant moment, would Lil Nas X become more respectable in his vocal production? I hear the smoothed-out remix vocals as a palimpsest, a writing-over that, in the traces of its editing, points to the fact that something has been changed, therefore never fully erasing the original’s over-affected refrain. These more respectable vocals seem to comport with Billboard’s expectations for what a country song should be, showing up in more acceptable garb to request admittance to the country chart, even as the new vocals smuggle in the memory of the original’s more roboticized lines.

As Lil Nas X shifted Billboard into a rhetorical checkmate with the release of the Billy Ray Cyrus remix, he also shifted his voice into a more respectable rendition of “can’t nobody tell me nothin,” removing the extreme application of pitch correction effects. This seems the opposite of what we might expect. The Billy Ray Cyrus remix is defiant, thumbing its nose at Billboard for not recognizing the countryness of the tune to begin with. Why, in a defiant moment, would Lil Nas X become more respectable in his vocal production? I hear the smoothed-out remix vocals as a palimpsest, a writing-over that, in the traces of its editing, points to the fact that something has been changed, therefore never fully erasing the original’s over-affected refrain. These more respectable vocals seem to comport with Billboard’s expectations for what a country song should be, showing up in more acceptable garb to request admittance to the country chart, even as the new vocals smuggle in the memory of the original’s more roboticized lines.

While the original vocals failed to achieve respectability by exposing the recording technologies of collaboration, the remix vocals fail to achieve respectability by exposing the social technologies of collaboration, feigning compliance and daring its arbiter to fail it all the same. The change in “Old Town Road”’s vocals from original to remix, then, stacks collaborative exposures on top of one another as Lil Nas X reminds the industry gatekeepers that can’t nobody tell him nothin, indeed.

_

Featured image, and all images in this post: screenshots from “Lil Nas X – Old Town Road (Official Movie) ft. Billy Ray Cyrus” posted by YouTube user Lil Nas X

_

Justin aDams Burton is Assistant Professor of Music at Rider University. His research revolves around critical race and gender theory in hip hop and pop, and his book, Posthuman Rap, is available now. He is also co-editing the forthcoming (2018) Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Music Studies. You can catch him at justindburton.com and on Twitter @j_adams_burton. His favorite rapper is one or two of the Fat Boys.

_

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Vocal Anguish, Disinformation, and the Politics of Eurovision 2016-Maria Sonevytsky

Cardi B: Bringing the Cold and Sexy to Hip Hop-Ashley Luthers

“To Unprotect and Subserve”: King Britt Samples the Sonic Archive of Police Violence-Alex Werth

Recent Comments