Surf, Sun, and Smog: Audio-Visual Imagery + Performance in Mexico City’s Neo-Surf Music Scene

Riding the Surf Wave in a City Without a Seashore

On April 24, 2005, at Zócalo square in downtown Mexico City, the Surf y Arena music festival gathered around 100,000 people and nine bands, ranging from local, barely known groups to big names in the new-wave surf music scene: Fenómeno Fuzz, Los Magníficos, Perversos Cetáceos, Espectroplasma, Los Elásticos, Yucatán A Go-Go, Sr. Bikini, Lost Acapulco, and Los Straitjackets, the latter being the only U.S. band in the festival. One year before, hardly more than a thousand people attended the event, organized in a smaller venue at Alameda del Sur, a few hundred yards south of Zócalo square. Perhaps not even the bands were prepared for the huge response in 2005. Interviewed by local newspaper La Jornada, Fenómeno Fuzz lead guitarist stated, “It’s the first time we see something like this, with so many people. Surf is an instrumental rock genre that was played in the 50s and 60s. There is no sand or sun here as in Acapulco, but we’ve brought downtown a bit of the beach vibe. In Mexico City there must be some 40 bands playing to this rhythm.” In the same interview piece, Lost Acapulco lead guitarist El Reverendo considered, “this festival is a success, for you realize this music is going up. People are on the same pitch. This is not a movement, but a style with many followers. […] It doesn’t matter if there is no beach here—you have to imagine it.”

Sr. Bikini at Rock and Road on 30 de Marzo 2013, Image by Flickr User José Miguel Rosas (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The bands who played at the 2005 Surf y Arena Festival wondered whether the success was transitory or would endure. More than a decade later, some are still active, most notably Lost Acapulco, whose singles and compilations have been released in countries like Spain, Italy, and Japan; they have toured around the world, and have released a new EP, Coral Riffs (2015). Los Straitjackets lead guitarist Danny Amis has collaborated with local surf bands like Lost Acapulco and Twin Tones; after surviving a hard battle against cancer, he moved to Mexico City’s Chinatown. Los Elásticos also released a new album, Death Calavera 2.2, the Espectroplasma members formed Twin Tones and have played, toured and participated in the short film inspired by their first record, Nación Apache. In 2016, the Wild’O Fest brought together old and new surf stars, starring The Fleshtones (U.S.) and Wau y los Arrrghs! (Spain), as well as local legends Los Esquizitos and Lost Acapulco. In February 2017, the Russian band Messer Chups toured across Mexico, playing with local bands in several cities. So it seems the scene is alive and kicking.

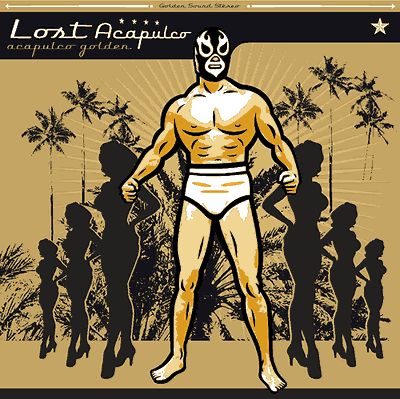

Lost Acapulco’s LP Acapulco Golden cover art by Dr. Alderete (2004). Masks became a famous trait of Mexican surf music. Danny Amys from Los Straitjackets and some Lost Acapulco members wear them on stage, as well as many other surf bands. This cover echoes films from the 50s and 60s featuring wrestlers like Santo and Blue Demon.

Today we can listen to how surf music shaped part of Mexico City’s underground music scene in the last decade of the 20th century and the early 21st. Being 235 miles away from Acapulco, one might wonder how wearing sandals, short pants, floral print shirts, plastic flower necklaces, and dark sunglasses became trendy in the country’s capital city. To this beach imagery, surf bands and fans added references to classic Mexican media icons, like wrestler Santo, comedian Mauricio Garcés, and black and white sci-fi movies. The work by visual artists like Dr. Alderete—who has designed covers and posters for many surf bands, such as Lost Acapulco, Fenómeno Fuzz, Telekrimen, The Cavernarios, Los Corona, among others—has been crucial for this imagery cross-reference process.

Lima-based visual art magazine Carboncito cover art by Dr. Alderete (2012). The cover features Kalimán, main character of an old Mexican comic strip, as well as other characters associated both with surf imagery (the Rapa Nui statue, oddly resembling a bamboo Tiki figure) and spy films like James Bond.

In this article I portray the neo-surf music scene in Mexico as a cultural-musical set of audiovisual and performative traits shared, modified, and transmitted by the scene’s partakers. It cannot be said there is a surf music “urban tribe” (a trendy concept for several years in Mexican youth studies), but rather shared “aesthetic” expressions of cultural syncretism, responding to the increase of atomization and alienation in Mexico City.

Just as in ska, punk, or hardcore rock, a number of surf concert attendees participate in typical genre-related rituals like moshing. Surf fans, however, are more “performatic” in the way Diana Taylor understands this term in The Archive and the Repertoire as “the adjectival form of the nondiscursive realm of performance” (6). Several surf concert goers wear masks, originally worn by notorious Mexican wrestlers like Santo, Blue Demon, and Rey Misterio (whose son would later become a WWE star). At the concert, when a song’s tempo suddenly stops or changes, masked dancers pose as if weightlifting, jump and crowd surf, stage fights, and mimic swimming movements. Surf music is the lyric-less soundtrack for the intertwined performance of different cultural traits, portraying a prolific tension between a hedonistic attitude associated with an invented nostalgia for West Coast surf culture, and the halo of exoticness surrounding Mexican culture in the U.S. imaginary, as portrayed by surf bands and artists (just to name a few, Herb Albert’s “Tijuana Taxi,” Link Wray’s “Tijuana,” and Los Straitjackets’ “Tijuana Boots”).

Mosh pit with masked participants. On stage, Lost Acapulco plays “Frenesick.” Multiforo Alicia, Mexico City, March 20 2009.

Tracing the Origins of Mexican Neo-Surf Music Scene

1960s Mexican rock and garage bands do not usually have instrumental songs in their repertoire, as is the case with Los Sleepers, or Los Rockin’ Devils. However, there are some examples of incursions in surf-related instrumentals, such as Los Teen Tops’ “Rock del diablo rojo,” or Los Locos del Ritmo’s  “Morelia.” It was not until Toño Quirazco (1935-2008) formed Quirazco y sus Hawaian Boys, though, that we find a Mexican instrumental song, “Surf hawaiiano,” explicitly using the noun “surf” as an identity marker, just like “Traveling Riverside Blues,” or “Jailhouse Rock”. The use of a pedal steel guitar (portrayed in their 1965 eponymous album cover photo), and its association to Hawaiian music through the slide guitar method, makes exotism an early sonic feature of Mexican surf. Born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Quirazco was not as famous as Los Teen Tops or Los Locos del Ritmo, but he is a key forerunner not only of surf music, as he is also known for having introduced ska to Mexican audiences, with songs like “Jamaica Ska” and “Ska hawaiano,” both off his album Jamaica Ska, also from 1965.

“Morelia.” It was not until Toño Quirazco (1935-2008) formed Quirazco y sus Hawaian Boys, though, that we find a Mexican instrumental song, “Surf hawaiiano,” explicitly using the noun “surf” as an identity marker, just like “Traveling Riverside Blues,” or “Jailhouse Rock”. The use of a pedal steel guitar (portrayed in their 1965 eponymous album cover photo), and its association to Hawaiian music through the slide guitar method, makes exotism an early sonic feature of Mexican surf. Born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Quirazco was not as famous as Los Teen Tops or Los Locos del Ritmo, but he is a key forerunner not only of surf music, as he is also known for having introduced ska to Mexican audiences, with songs like “Jamaica Ska” and “Ska hawaiano,” both off his album Jamaica Ska, also from 1965.

Although surf music bands suffered heavily with the arrival of the British Wave, not all of them disappeared. Bands such as The Ventures became famous for covering surf standards. Others, like The Beach Boys, eventually migrated to different music styles. Later in the 1970s and 80s, bands like The Cramps, The Stray Cats, and The Go-Go’s kept alive surf-related styles, so that by the time Pulp Fiction appeared, in 1994, there were some interesting bands we already can consider “neo-surf,” such as Man Or Astroman? and The Tantra Monsters; Los Straitjackets re-formed and Dick Dale began touring again. Quentin Tarantino’s soundtrack to Pulp Fiction (including songs by Southern California surf rockers Dale, The Tornadoes, The Revels, The Centurians, and The Lively Ones) contributed to bringing surf music back to mainstream attention, now as a vintage sound commodity (Norandi, 2002).

We might call this “the Pulp Fiction effect,” a phenomenon recognized by stakeholders in the scene, like Los Esquizitos guitar and theremin player Güili:

One day Nacho came up with the idea that we should play surf, because it was the moment in which […] in Satélite [a northern Mexico City neighborhood ] all bands wanted to play funk like Red Hot Chili Peppers or Primus. It became a virtuoso slap competition, and precisely no one was playing surf […]. Shortly afterwards, Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction was released and surf exploded impressively with the movie’s theme. But we were already riding the surf wave.

Multiforo Alicia has been an important venue for the consolidation not only of a surf scene, but also of other emerging movements at the time. Founder and owner Ignacio Pineda remembers,

When we started Multiforo Alicia [in 1995], there was a generational shift. There were a lot of new bands that didn’t fit into what had been going on in the last 10 or 11 years, and they were the punk rock, ska, hip-hop, transmetal, emo, and nu metal movements, which nowadays are quite normal. […] Luckily for us, [Alicia] was like home for all of them.

Interview with Multiforo Alicia owner Ignacio Pineda, 2011

It is a common venue for surf bands (Norandi, 2002, Caballero, 2012), and through their recording label, Grabaxiones Alicia, they have produced albums for some of the most interesting instrumental rock projects in Mexico, among them Twin Tones/Espectroplasma/Sonido Gallo Negro (three groundbreaking bands with the same members), Los Esquizitos, Los Magníficos, Telekrimen, The Cavernarios, and Austin TV. Massive festivals and concerts, like Vive Latino or Surf y Arena, have also contributed to positioning neo-surf as an ongoing trend in alternative rock.

Masking Identity, Performing Difference

While the emergence of Mexican neo-surf was contingent upon local and international music trends in the mid-90s, its permanence has been due to processes of cultural syncretism and appropriation. Wrestler masks are a good example. Worn first by Danny Amis, and later on by Los Esquizitos and Lost Acapulco, masks quickly spread out as a neo-surf visual icon. Los Esquizitos drum player, Brisa, doesn’t remember there being an aesthetic justification behind the masked man using a chainsaw portrayed in their first album cover. Nacho complains, “Argh! We created a monster unawares! Ah, I sometimes regret that. I really regret having worn masks at a concert.”

Los Esquizitos greatly contributed to blend a Mexican surf flavor through their imagery on stage, as well as with their most emblematic song, “Santo y Lunave.” One of the few songs with lyrics in the scene (and with spoken word rather than singing), it tells story of how Santo got lost in space, turning him into an important figure of Mexican neo-surf imagery. As Güili recognizes, “I think it was after the ‘Santo’ song when all the Tetris pieces fit perfectly into place—wrestling, masks, floral print shirts, surf— everything in the same box.”

Live version of “Santo y Lunave” by Los Esquizitos, Vive Latino Music Festival, Mexico City, May 17, 2009. The song was originally released in their first LP (1998)

“Performatic” moshing is another example of cultural appropriation. The apparently random movements of moshers in heavy metal concerts have been compared to the kinetics of gaseous particles (as in Silverberg, Bierbaum, Sethna & Cohen’s “Collective Motion of Moshers”) but in surf concerts their movements cannot be reduced to the categories of “self-propulsion,” “flocking” and “collision.” Here moshers interact in more complex ways, mimicking wrestling movements to the rhythm of the song in turn, enacting fights between masked and unmasked opponents, and helping other moshers to jump over the audience and crowd surf. They consciously perform the icons they associate with surf culture. They are aware of the differential traits existing between this and other rock sub-genres, and they externalize them through ritualized behaviors. In other words, Mexican surf concert goers adopt moshing to participate in simulacra about stereotyped representations of Mexican culture and subjects.

Dancing Desires

In his book Popular Music: The Key Concepts (2nd ed), Roy Shuker describes surf as “Californian good time music, with references to sun, sand and (obliquely) sex” (2005, 262). This sexual suggestiveness is still present in Mexican neo-surf, as can be noticed in songs like Fenómeno Fuzz’s “El bikini de la chica popof” [“The Snob Girl’s Bikini”]:

Ella viene caminando en su bikini de color,

ella viene caminando y a todos nos da calor,

y sus piernas bien bronceadas me hacen suspirar.

Ella viene caminando y no ve a nadie más.

[She’s walking by, wearing her colorful bikini,

she’s walking by and everyone gets hot,

and her well-tanned legs make me sigh.

She’s walking by and doesn’t look at anyone else]

Other bands seem to reinforce this fetishization. Sr. Bikini have sometimes hired women dancers wearing masks and bikinis for their shows, and Los Elásticos have a permanent member, La Chica Elástica, who dances in every live show.

[Final part of a Los Elásticos concert in 2012, featuring La Chica Elástica. All-men and all-women mosh pits can be seen at 0:40 and 3:36.]

However, even though sometimes subject to hedonistic and stereotyped representations, women participate in every level of the scene, expressing agency as band members, scenemakers, and/or fans. Women play in the most representative bands, such as Fenómeno Fuzz’s former singer and bass player, Biani, or Los Esquizitos drummer, Brisa. There are also all-woman bands, such as Las Agresivas Hawaianas (whose brief existence is scarely documented on the internet), rockabilly trio Los Leopardos, and garage-oriented Ultrasónicas, whose members have continued playing solo, most notably Jessy Bulbo.

Offstage, both genders wear masks and enter the pit. Sometimes, when there are many moshers, men and women gather in separate pits. Dancing is much more prominent in the surf scene than in punk; participants appropriate a go-go, swing, rock ‘n’ roll, and ska dancing moves, mixing them with wrestling and weightlifting positions. The attendees accomplish their middle-class expectations of leisure and entertainment by showing off their outfits, feeling desire, desired and/or admired (even if ironically) through dancing and moshing—literally by performing such expectations in situ.

The scene overall, has been critiqued for being too retro and insulated from political critique. As La Jornada‘s Mariela Norandi points out, “an element that the Mexican movement has inherited from the origins of surf is the lack of ideology. Curiously, surf is reborn in Mexico in a moment of political and social unrest [in the mid-90s], with the Zapatista uprising, the peso devaluation, Colosio’s murder, and Salinas’ escape” (2002, 6a). The fact that this scene has survived for over two decades, despite the many economic and political crises Mexico has faced ever since, suggests it works as an ideological outlet for scene partakers to elude their social reality. Just as it happened in the 60s with the Vietnam War, once again surfers stay away from social and political problems, and reclaim their right to have fun and dance. They wear their floral print shirts and dance a go-go style, remembering those wonderful 60s (6a). For Norandi, the lack of lyrics in surf music may be partly responsible for most surf bands seemingly uncritical position.

Into the Surf Sound

Although half of Mexico’s states have a seashore, surf music in the capital is related to everything but actual surfing. The imagery built around it, considered “surrealistic” by Norandi (6a), is the most visible novelty in the new scene, since melodically and rhythmically speaking surf remains fairly simple, like garage or punk. However constrained, like other genres, to the 12-bar blues progression, it is in timbre where we appreciate how surf sound has been defined by several generations of music bands and players. A triple-level approach to surf music (timbral, melodic, and stylistic) can account for the creation and development of several genres or scenes associated to the rise of Mexican neo-surf, like chili western (Twin Tones, Los Twangers, The Sonoras), space surf (Espectroplasma, Telekrimen, Megatones), garage (Ultrasónicas, Las Pipas de la Paz) and rockabilly (Los Gatos, Eddie y Los Grasosos, Los Leopardos, among many others).

Appropriation, practiced through covering standards and imitating riffs and melodies, has been always crucial for shaping the surf sound, just as it was in preceding genres that influenced rock ‘n’ roll, like blues, twist, and jazz. Although not exactly referred to as “surf standards,” there are some foundational songs that shaped the surf sound. Three pieces nowadays still debated as the first surf song—Duane Eddy’s “Rebel Rouser,”Link Wray’s “Slinky,” and Dick Dale’s “Miserlou”—influenced not only contemporary bands and their immediate successors, but also musicians in the ’90s wave.

These and other composers contributed collectively to establishing surf music’s standard traits: the 4/4 drum beat (whose earliest template may be Dale’s “Surf Beat”), the “wavy guitar” riff (perfectly illustrated in the beginning of The Chantay’s “Pipeline”), an extensive use of reverb, and the appropriation of “exotic” tunes (such as the Lebanese melody that inspired Dale’s tremolo style in “Miserlou”). Many surf songs contain, in particular, traits from “Slinky’s” guitar and “Surf Beat’s” drums. Both are simple and repetitive, but can be combined with other arrangements at will. This formula has been used in countless surf songs ever since.

Covering is a way of making connections with specific songs, and paying homage to (or deflating) admired bands and musicians. Links between a band and certain collaboration networks are thus established. Sr. Bikini covered Alpert’s instrumental version of The Beatles’ “A Taste of Honey,” setting up a dialogue with a musician that played a lot with Mexican stereotyped imagery and sounds (like the trumpets, substituted by electric guitars in Sr. Bikini’s version).

Covering is a way of making connections with specific songs, and paying homage to (or deflating) admired bands and musicians. Links between a band and certain collaboration networks are thus established. Sr. Bikini covered Alpert’s instrumental version of The Beatles’ “A Taste of Honey,” setting up a dialogue with a musician that played a lot with Mexican stereotyped imagery and sounds (like the trumpets, substituted by electric guitars in Sr. Bikini’s version).

Lost Acapulco renamed The Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird” as “Surfin’ Band,” participating in a long chain of covers (including The Cramps and The Ramones) of a song that in turn was the result of mixing two pieces by The Rivingtons, “Bird’s The Word” and “Papa Oom Mow Mow.” Los Esquizitos have their own covers of The Cramps’ “Human Fly” (“El moscardón”) and Rory Erickson’s “I Walked With A Zombie.”

Los Magníficos’ “Píntalo de negro,” after The Rolling Stone’s “Paint It Black,” shows that, just as in punk, any piece can be turned into a surf song.

Sometimes it is just a trait (a riff, or a beat) that is referenced. Fenómeno Fuzz’s initial riff in “Tiki Twist” resembles Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” whereas two chili western songs (“Transgenic Surfers” by Los Twangers and “Skawboy” by The Bich Boys) echo The Ramrods’ harmonic and timbral arrangements for “Riders In The Sky,” another song with a long cover history, including Dale, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley. A surf version of this song was familiar to Mexican TV viewers in the 90s, since it was a regular soundtrack of furniture store Hermanos Vázquez spots.

Surf was born at a time when stand-alone effects units were just about to change the way music was made, taking audio manipulation off the studio and bringing it to the stage. For example, The Shadows are known for having used the tape-based Watkins Copicat, “the first repeat-echo machine manufactured as one compact unit” according to Steve Russell, responsible for the guitar delay effect in their 1960 rendition of Jerry Lordan’s “Apache,” since then a surf standard. In his book Echo and Reverb, for example, Peter Doyle examines how effects like echo/delay and reverb shaped sonic spatiality in 20th century popular music recording in the U.S., from hillbilly, country, blues, and jazz to rock ‘n’ roll.

Although Doyle only dedicates a few paragraphs to Dale, Wray, and surf instrumentals, acoustic effects greatly contributed to characterize their styles as well. Some traits are intricately related to genre specific manifestations, like the double bass in rockabilly, or the twang effect in chili western. Timbre, then, is the aural counterpart to the scene’s visual aspect, “invoking the rich semiotic traditions that wove through southern and West Coast popular music recording” (Doyle, 2005, 226). It has become a way both to continually define the genre and, in the Mexical neo-surf scene in particular, to overcome melodic and harmonic limitations. Thanks to timbral play, what used to be a blind alley in rock history became in the 1990s a mirror for young generations of Mexicanos to create and feel aligned with fashionable trends, and a sonic filter enabling them to examine their social situations and, sometimes, to willfully sidestep them.

—

Featured Image: Lost Acapulco in Estadio Azteca 2009, Image by Flickr User Stephany Garcia (CC BY-ND 2.0).

—

Aurelio Meza (Mexico City, 1985) is a PhD student in Humanities at Concordia University, Montreal. Co-organizer of the PoéticaSonora research group at UNAM, Mexico City, where he is in charge of designing and developing a digital audio repository for sound art and poetry in Mexico since 1960. Author of the books of essays Shuffle: poesía sonora (2011) and Sobre Vivir Tijuana (2015). Blog: http://aureliomexa.wordpress.com/

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Visibility in Anglo-Latin Prose

Here is a distilled introduction to the latest installment of Medieval Sound, Aural Ecology, by series co-editors Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman. To read their previous introduction, click here. To read the first run of the series in 2016, click here. To read the full introduction to “Aural Ecology” and to read last week’s post by Thomas Blake, click here.

Aural Ecology

What is considered music, noise, or harmony is historically and culturally contingent. [. . .] The essays in “Aural Ecologies” address the issue of unharmonious sounds, sounds that often mark dissonant critical identities—related to race, religion, material—that reverberate across different soundscapes/landscapes. In this way, this group of essays begins to open up the stakes of Medieval Sound in relation to what contemporary sound studies has begun to address in relation to cultural studies, architectural and environmental soundscapes, and the marking of race through the vibrations of the body. —Dorothy Kim and Christopher Roman

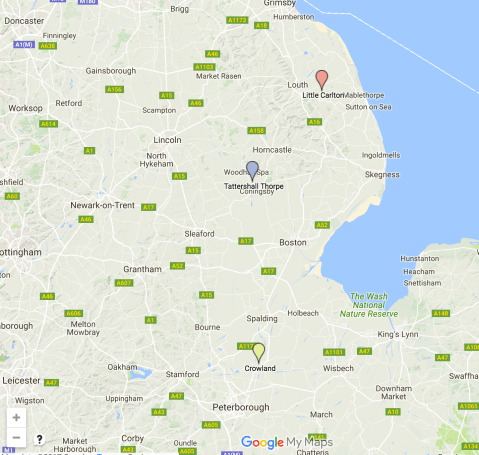

While the raucous rancor of last year’s Super Tuesday was dominating network news and social networks—which, sadly, seems so long ago now—a quieter news story emerged from the tranquil fields of Lincolnshire: an Anglo-Saxon island has been discovered. Its artifacts are some of the most remarkable to have been found in recent decades; among these finds are writing utensils, game pieces, butchered animal bones, and other indicators of a sustained trading community.

The Guardian reported that surveys and software enabled the archaeologists to model the island in its contemporary landscape and seascape, revealing that it had once rested “between a basin and a ditch.”

This placement, the lead archaeologist continued, suggests that the site “was a focal point in the Lincolnshire area, connected to the outside world through water courses.” So if these reimagined waterways can show us how people saw the site, can they tell us how people heard it, as well?

I think so, especially because of the recent work on ancient acoustics in early churches. In February, The Atlantic published an article on the recent scholarly collaboration among an art historian-archaeologist, a music producer-engineer, and the founder of the USC Immersive Audio Laboratory (yes, it’s a real thing). This super-interdisciplinary team was able to “map the acoustic fingerprint of several [Byzantine] churches,” which were shown to have been deliberately “designed to shift a person’s sensory experience.” Now, the USC member explains, they can record a chant, “process it … and all of the sudden we have performances happening in medieval structures.” They can actually rebuild the sounds of our ancient past. [By the way, Allison Meier of hyperallergic reported on this story as well; her article provides links to the Escape Velocity podcast on Acoustic Museums, which is well worth a listen].

Interior of Lincoln Cathedral, Image by Flickr User Gary Ullah, (CC BY 2.0)

If they can recreate the lost sounds of ancient structures, and archaeologists can recreate early medieval topographies, then it stands to reason that the recreation of past landscapes, and even seascapes, might not be far behind.

But was sound different across the cooler, wetter climate of the early Middle Ages? Were the hearers’ auditory contexts drastically different in a pre-modern world? To what effect?

To me, what’s tantalizing about the Lincolnshire island is that it was on the border of the early medieval fenland—an area described by the 8th-century monk Felix as dense and undulating, “now consisting of marshes, now of bogs, sometimes of black waters overhung by fog, sometimes studded with wooded islands and traversed by the windings of tortuous streams” (Ch XXIV, trans Colgrave p 87). In such an aqueous environment, sound would have travelled well, staying close to the cool, dense air hovering over the waters.

Dark skies over fenlands, near Spilsby, Lincolnshire. Taken by Lutmans on Flickr, (CC BY 2.0).

In his prose hagiography, the Life of St Guthlac, Felix enshrines certain sounds in the wetland ecology of Guthlac’s surroundings. He does so most explicitly at the landing-place, where visitors must “sound a signal” to alert the hermit that they’ve arrived. But what was this signal, and why would Felix bother to emphasize such a mundane practice of alerting your host when you’ve arrived?

In monastic communities bells were used to sound the Daily Office to calling each member together in prayer. As moderns, we should remember that these bells—frequent, sonic interventions of everyday life—were rung on the shore, or in a church, or on monastic grounds rather than from the larger towers of later belfries (an exception to this is the early Irish Round Tower). These small hand-held bells “of hammered sheets or cast metal” which “would presumably have clanged or tinkled, rather than tolled sonorously across a distance” (Resounding Community, 103).

Bell-shrine; bronze and silver parcel-gilt; made for the bell of St Conall Cael.

Bells were spiritual and supernatural; they could cleanse or curse, and were kept by clerics and lay people alike. They were sometimes sworn on, as if they were relics. Sometimes, they were made into relics. For more about early Irish bell traditions, click here and or/ here.

In Northwest Europe in the Early Middle Ages, Christopher Loveluck describes David Hinton’s work on a seventh-century smith found buried alone, “next to the marshland and waterways to the sea, with his tools, a bell, a fine seax and a silk-wrapped amulet” and therefore “emblematic of the transition from such ‘outsider’ itinerant artisan/merchants to the vibrant artisan and trading communities of the emporia ports.” Still, the“[p]erception of threat from itinerant ‘outsiders’ is emphasized in the late seventh-century Anglo-Saxon law code of Wihtred, by the obligation on non-local travellers and foreigners to announce themselves with bells or horns, prior to leaving principal roads or trackways to approach settlements.”

For seventh-and eighth century people, then, bells sounded time, community, and stillness as well as place, strangeness, and travel. In either instance, the aural intrusion always betokened a human presence. And of course, these were some of the only sounds that weren’t naturally occurring; this might have been as close as they got to manmade sound pollution.

For Guthlac, sound was especially important because he could not see far from his earthen hermitage. Not having any need for a bell to sound the Daily Office, he nevertheless depended on some kind of signal for approaching visitors.

In one episode, distraught parents bring their once-possessed, now very ill son to Crowland in the hope that he might be cured. This is quite different from an earlier visitation from Wilfrid and Æthelbald, whom Guthlac knew personally, and with whom he might have traded correspondence. To me, this is the real test of Guthlac’s grace: will he help the neediest? The stranger? The tired, desperate parents? Does the bell, or whatever the signal is, proclaim their sameness or difference?

We can sense the tension in the passage, during their sounding of the signal and speaking to Guthlac:

Then when the sun rose in its splendour, they approached the landing place of this said island, and having struck the signal they begged for a talk with the great man. But he, as was his custom, burning with the flame of most excellent charity, presented himself before them…[and after hearing their story] immediately seized the hand of the tormented boy and led him into his oratory, and there prayed on bended knees, fasting continually for three days…(XLI, Colgrave 131).

The parents had expected to wait; they expected to plead on their son’s behalf. They expected a struggle to be heard. But—and I do think that’s a rather crucial autem in the Latin—Guthlac is eager to listen; the sound on the shore was enough.

What’s more, his cure is a series of utterances. He prays (aloud) for three days straight, without pausing to eat. And after ritually rinsing and breathing the “breath of healing” on the boy, the child, “like one who is brought into port out of the billows and the boiling waves, heaved some deep sighs from the depth of his bosom and realized that he had been restored to health”(XLI, Colgrave 131).

Image from National Museum of Ireland

I’m a mom to an asthmatic toddler, so I find myself quite moved by this scene. I can imagine ringing the bell—the thing I might have heard in church, or had in my home; the signal by which monks were called to prayer and children inside for curfew—to make a sound for myself. I can imagine traveling with my husband to a strange place far from home, not knowing what would happen. I can imagine using something everyday for something extraordinary, and having the sound of my arrival echo with anticipation. If I were this mother, I would hear it bounce off the marshes and off the low-lying islands. The dawn would be warming the air above us, amplifying our sound. And I would be standing there, with my child wrapped in my arms, hoping to see someone emerge from a barrow; a man of God whose isolation and entrenchment was supposed to be part of his holiness.

The sound travels outwards to the hermitage and back with the hermit—the echo of her hope, meeting them at the shore. This is a soundscape and a landscape in which time seems still on the shore, but sped through in the oratory. Felix joins both sites, and both temporalities, with the simile of the boy as one rescued from shipwreck catching his breath as he washes ashore. The image recalls the sound of their arrival, and that first bell still seems to ring through this narrative of hope against all odds.

Wouldn’t it be great to hear that again?

—

Featured Image: Guthlac sailing to Crowland with Tatwin. © British Library, Harley Roll, Y 6, roundel 4, from Medieval Histories.com

—

Rebecca Shores is a Ph.D. candidate in English Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her Dissertation is entitled “Bringing Saints to the Sea: Ships in Old English and Anglo-Latin Hagiography.”

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

(Sound)Walking Through Smithfield Square in Dublin–Linda O’Keeffe

Wayback Sound Machine: Sound Through Time, Space, and Place–Maile Colbert

Audiotactility & the Medieval Soundscape of Parchment–Michelle M. Sauer

Recent Comments