Listen to the Sound of My Voice

Betrayal

I first realized there was a problem with my voice on the first day of tenth grade English class. The teacher, Mrs. C, had a formidable reputation of strictness and high standards. She had us sit in alphabetical order row after row, and then insisted on calling roll aloud while she sat at her desk. Each name emerged as both a command and a threat in her firm voice.

“Kelly Barfield?”

“Here,” I mumbled quietly. I was a Honor Roll student with consistent good grades, all A’s and one B on each report card, yet I was shy and softspoken in classes. This was an excellent way to make teachers amiable but largely go unnoticed. The softness of my voice made me less visible and less recognizable.

Mrs. C repeated my name. Caught off guard, I repeated “here” a little more loudly. She rose to her feet to get a better look at me. I knew what she saw: a petite girl with long ash blonde hair, big brown eyes, and overalls embroidered with white daisies on the bib. When her gaze finally met mine, Mrs. C frowned at me and cleared her throat loudly. I curled into my desk, hoping to disappear.

“Lincoln High School 9-16-2007 008” by Flickr user Paul Horst, CC BY-NC 2.0

“Miss Barfield, did you hear me call your name twice? In this class, when I call roll, you respond.” I gave a quick nod, but Mrs. C wasn’t finished: “We use our strong voices in here, not our girly, breathy ones.” My cheeks flushed red while Mrs. C droned on about confidence and classroom expectations.

“Do you understand me?”

I stammered a “yes.” Mrs. C turned her attention back to the roll call. Her harsh words rang in my ears. I sank low in my chair, humiliated and angry. I couldn’t help that I sounded girly: I was, in fact, a girl. This was the way my voice sounded. It was not an attempt to sound like the dumb blonde she appeared to think I was.

That day I decided that I would never speak up in her class. Forget the Honor Roll. If the sound of my voice was such a problem, then my mouth would remain firmly shut in this class and all of my others. I would never speak up again.

“Listen” by Flickr user lambda_x, CC BY-ND 2.0

My vow to stop speaking lived a short life. I enjoyed Mrs. C’s serious fixation on diagramming sentences and her attempts to show sophomores that literature offered ideas and worlds we didn’t quite know. At first, I spoke up with hesitation and fear of the inevitable dismissal, but I continued to speak. Becoming louder became my method to seem confident, even when I felt anything but.

Throughout high school, my voice emerged again and again as a problem. Despite the increased volume, my voice still sounded tremulous, squeaky, hesitant, and shrill to my own ears. Other girls had these steady, warm voices that encouraged others to listen to them. Some had higher voices that were melodic and lovely. I craved a lower, more resonant voice, but I was stuck with what I had. In drama club, our director scolded me with increasing frustration about my tendency to end my lines in the form of a question. My nerves materialized as upspeak. The more he yelled at me, the more pronounced the habit became. He eventually gave up, disgusted by my inability to control my vocal patterns.

By Dvortygirl, Mysid [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, at a big state university in my native Florida, I learned quickly that a Southern accent marks you as a dumb redneck from some rural town that no one had heard of. Students in my classes asked me to say particular words and then giggled at my pronunciations. “You sound like a Southern belle,” one student noted. This was not really a compliment. According to my peers, Southern belles didn’t have a place in the classroom. Southern belles didn’t easily match up with “college student. As a working-class girl from a trailer park, I learned that I surely didn’t sound like a college student should. I worked desperately to rid myself of any hint of twang. I dropped y’all and reckon.

I listened carefully to how other students talked. I mimicked their speech patterns by being more abrupt and deadpan, slowly killing my drawl. When I finally removed all traces of my hometown from my voice, my friends both from home and from college explained that now I sounded like an extra from Clueless. My voice was all Valley girl. I was smarter, they noted with humor, than I sounded and looked. My voice now alternated between high-pitched and fried. Occasionally, it would squeak or crack. I thought I sounded too feminine and too much like an airhead, even when I avidly tried not to. I began to hate the sound of my voice.

My voice betrayed me because it refused to sound like I thought I needed it to. It refused to sound like anyone but me.

When I started teaching and receiving student evaluations, my voice became the target for students to express their displeasure with the course and me. According to students, my voice was too high and grating. Screechy, even: one student said my voice was at a frequency that only bats could hear. In every set of evaluations, a handful of students declared that I sounded annoying. This experience, however, was not something I alone faced. Women professors and lecturers routinely face gender bias in teaching evaluations. According to the interactive chart, Gender Language in Teaching Evaluations, female professors are more likely to be called “annoying” than their male counterparts in all 25 disciplines evaluated. The sound of my voice was only part of the problem, but I couldn’t help but wonder if how I sounded was an obstacle to what I was teaching them.

Once again, I tried to fix my problematic voice. I lowered it. I listened to NPR hosts in my search for a smooth, accentless, and educated sound, and I attempted to create a sound more like them. I practiced pronouncing words like they did. I modulated my volume. I paid careful attention to the length of my vowels. I avoided my natural drawl. None of my attempts seemed to last. Some days, I dreaded lecturing in my courses. I had to speak, but I didn’t want to. I wondered if my students listened, but I wondered more about what they heard.

Sound

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1393933

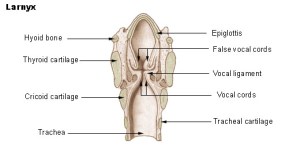

The sound of your voice is a distinct trait of each human being, created by your lungs, the length of your vocal cords, and your larnyx. Your lungs provide the air pressure to vibrate your vocal cords. The muscles of your larnyx adjust both the length and the tension of the cords to provide pitch and tone. Your voice is how you sound beyond the resonances that you hear when you speak. It is dependent on both the length and thickness of the vocal cords. Biology determines your pitch and tone. Your pitch is a result of the rate at which your vocal cords vibrate. The faster the rate, the higher your voice. Women tend to have shorter cords than men, which makes our voices higher.

Emotion also alters pitch. Fright, excitement, and nervousness all make your voice sound higher. Nerves would make a teenage girl have an even higher voice than she normally would. Her anxious adult self would too. Her voice would seem tinny because her larnyx clenched her vocal cords tight. Perhaps this is the only sound she can make. Perhaps she is trying to communicate with bats because they at least would attempt to listen.

Biology, the body, gives us the voices we have. Biology doesn’t care if we like the ways in which we sound. Biology might not care, but culture is the real asshole. Culture marks a voice as weak, grating, shrill, or hard to listen to.

“Speak” by Flickr user Megara Tegal, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

My attempts to change my voice were always destined to fail. I fought against my body and lost. I couldn’t have won even if I tried harder. My vocal cords are determined that my voice would be high, so it is. The culture around me, however, taught me to hate myself for it. Voice and body seem to cast aspersions on intelligence or credentials. It’s the routineness of it all that wears on me. I expect the reactions now.

I wonder if I’m drawn to the quietness of writing because I don’t have to hear myself speak. I crave the silence while simultaneously bristling at it. Why is my voice a problem that I must resolve to placate others? How can I get others to hear me and not the stereotypes that have chased me for years?

Fury

My silence has become fruitful. The words I don’t say appear on the page of an essay, a post, or an article. I type them up. I read aloud what I first refused to say. I wince as I hear my voice reciting my words. I listen carefully to the cadence and tone. This separation of words and voice is why writing appeals to me. I can say what I want to say without the sound of my voice causing things to go awry.

People can read what I write, yet they can’t dismiss my voice by its sound. Instead, they read what I have to say. They imagine my voice; my actual sound can’t bother them. But, they aren’t really hearing me. They just have my words on the page. They don’t know how I wrap the sound around them. They don’t hear me.

Rebecca Solnit, in “Men Explain Things to Me,” writes “Credibility is a basic survival tool.” Solnit continues that to be credible is to be audible. We must be heard to for our credibility to be realized. This right to speak is crucial to Solnit. Too many women have been silenced. Too many men refuse to listen. To speak is essential “to survival, to dignity, and to liberty.”

“Listen” by Flickr user Emily Flores, CC BY-ND 2.0

I agree with her. I underline her words. I say them aloud. The more I engage with her argument, the more I worry. What about our right to be heard? When women speak, do people listen? Women can speak and speak and speak and never be heard. Our words dismissed because of gender and sound. Being able to speak is not enough, we need to be heard.

We get caught up in the power of speaking, but we forget that there’s power in listening too. Listening is political. It is act of compassion and empathy. When we listen, we make space for other people, their stories, their voices. We grant them room to be. We let them inhabit our world, and for a moment, we inhabit theirs. Yes, we need to be able to speak, but the world also needs to be ready to listen us.

We need to be listened to. Will you hear me? Will you hear us? Will you grant us room to be?

When I think of times I’ve been silenced and of the times I haven’t been heard, I feel the sharp pain of exclusion, of realizing that my personhood didn’t matter because of how I sounded. I remember the burning anger because no one would listen. I think of the way that silence and the policing of how I sound made me feel small, unimportant, or disposable. As a teenager, a college student, and a grown woman, I wanted to be heard, but couldn’t figure out exactly how to make that happen. I blamed my voice for a problem that wasn’t its fault. My voice wasn’t the problem at all; the problem was the failure of others to listen.

“listen” by Flickr user Jay Morrison, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Loss

While writing this essay on my voice, I almost lost mine, not once but twice. I caught a cold and then the flu. My throat ached, and I found it difficult to swallow. A stuffy nose gave my voice a muted quality, but then, it sounded lower and huskier. I could hear the congestion disrupting the timber of my words. My voice blipped in and out as I were radio finding and losing signal. It hurt to speak, so I was quiet.

“You sound awful,” my husband said in passing. He was right. My voice sounded unfamiliar and monstrous. I tested out this version of my voice. It was rougher and almost masculine. I can’t decide if this is the stronger, more authoritative voice I wanted all along or some crude mockery of what I can never really have. I couldn’t sing along with my favorite songs because my voice breaks at the higher register. I wheezed out words. I croaked my way through conversations. “Are you sick?” my daughter asked, “You don’t sound like you.”

Her passing comment stuck with me. You don’t sound like you. Suddenly, I missed the sound of my voice. I disliked this alien version of it. I craved that problematic voice that I’ve tried to change over the years. I wanted my voice to return.

After twenty years, I decided to acknowledge the sound of me, even if others don’t. I want to be heard, and I’m done trying to make anyone listen.

—

Featured image: “Speak” by Flickr user Ash Zing, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

—

Kelly Baker is a freelance writer with a religious studies PhD who covers religion, higher education, gender, labor, motherhood, and popular culture. She’s also an essayist, historian, and reporter. You can find her writing at the Chronicle for Higher Education‘s Vitae project, Women in Higher Education, Killing the Buddha, and Sacred Matters. She’s also written for The Atlantic, Bearings, The Rumpus, The Manifest-Station, Religion Dispatches, Christian Century’s Then & Now, Washington Post, and Brain, Child. She’s on Twitter at @kelly_j_baker and at her website.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies — Christine Ehrick

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice– Yvon Bonefant

As Loud As I Want To Be: Gender, Loudness, and Respectability Politics — Liana Silva

This is What It Sounds Like . . . . . . . . On Prince (1958-2016) and Interpretive Freedom

Can you imagine what would happen if young people were free to create whatever they wanted? Can you imagine what that would sound like?–Prince, in a 2015 interview by Smokey D. Fontaine

Prince leaves an invitingly “messy” catalog—a musical cosmos, really—just as rich for those who knew it well as for those encountering it with fresh ears. He avoided interviews like he avoided conventions. He made few claims. Read him as you will.

We are free to interpret Prince, but not too free. Yes, art is open, and perhaps Prince’s art especially. And yet many eulogies have described him as indescribable, as if he were untethered by the politics of his world; he wasn’t. Some remembrances assume (or imagine) that Prince was so inventive that he could escape stultifying codes and achieve liberation, both as musician and human being. For example, Prince has often been called “transcendent”—of race, of musical genre, even of humanity itself. This is overstated; he was rooted in all of these. Better to say, maybe, that he was a laureate of many poetics, some musical and some not. He responded to race, genre, and humanity, all things that he and we are stuck with. He was a living artwork, and these, by way of sound, were his media.

Prince was not transcendent. He was just too much for some to assimilate.

Since Prince’s passing last month, I’ve been struck by the idea that his career might have been, deliberately or not, an elaborate quotation of the career of Little Richard, who anachronistically has outlived him. Or, a sonic version of what Henry Louis Gates Jr. calls “signifyin(g)” in the African American artistic tradition in The Signifying Monkey: repetition with a difference, a re-vision—and, especially appropriate here—a riffing (66). Both Prince and Richard in their way defined rock music, even as rock—as a canonized form—held them at a distance. They were simultaneously rock’s inventive engine and its outer margins, but never, seemingly, its core—at least from the perspective of its self-appointed gatekeepers.

![]()

Rock and race have, to put it mildly, an awkward history. African-American rock artists rarely get their due from labels and taste-making outlets, in money or posterity, a phenomenon not at all limited to the well-known pinching of Elvis and Pat Boone. One might consider, for example, Maureen Mahon’s anthropology of the Black Rock Coalition, a group home to Greg Tate, Living Colour, and others dwelling on rock’s periphery. Canons are one way to understand how this denial works.

To be sure, some black artists have been canonized in rock, but always with a handicap, as Jack Hamilton has explained lucidly. In, for example, best-of lists (which I have browsed obsessively since Prince died, as if enshrinement there might confirm something about him; he is usually #40 or #50), there are only so many slots of color: Hendrix is the black guitar god; Little Richard the sexual sentinel rising in a repressed era; James Brown the lifeline to funk; Big Mama Thornton the grandmaternal footnote. Best-of lists published by major magazines and websites such as Rolling Stone and VH1, tend to name about 70% white artists, as well as 90-95% male ones. These lists have become just a smidgen more inclusive in the past decade or so. Still, only the Beatles and Rolling Stones are regular contenders to be named history’s greatest rock band.

We are free to interpret greatness, but not too free.

For those who care about lists enough to comment on them, much of the point is in the arguing, the freedom to declare an opinion that cannot be challenged on logical grounds. I certainly wouldn’t argue for more “correct” best-of lists, either for aesthetics or inclusivity. Lists have every right to be subjective. But they are also fascinatingly unmoored by any explicit standard for judgment. As a result, the debates that surround their ordering are full of unvarnished pronouncements of truth (and falsity), even for those who acknowledge the subjectivity of lists, which I observed first hand as I joined and posted on a Beatles forum and an Eagles forum to research this article (“…putting the Police and the Doors ahead of the Eagles is absurd, IMHO”). But why would anyone declare certainty about a question such as the best rock artist of all time, when it is so plainly open to personal interpretation?

Yes, lists are subjective. But who are the subjects that invest in them?

![]()

Prince’s career began in the late 1970s, a musical moment deeply reflective of what Robin DiAngelo calls “white fragility.” The Beatles were gone after the 1960s and guitar music stood under their long shadow. Led Zeppelin were bloated and breaking up. Disco was in ascent. Rock had somehow convinced itself that it was neither rooted in nor anchored by queer, female, and racially marked bodies, as it indeed was and in fact had always been. White male rock critics and fans were busily constructing the “rock canon” as a citadel—impenetrable to “four on the floor beats” and diva-styled vocals—and there was nothing in its blueprint to suggest that there would be a door for someone like Prince.

Just one month after Prince finished recording his breakthrough, self-titled album in July 1979—the record gave us “I Wanna Be Your Lover” and “I Feel For You,” which Chaka Khan would take to chart topping heights in 1984—Chicago “shock jock” Steve Dahl staged an infamous event at Comiskey Park called Disco Demolition Night. The fascistic spectacle, which took place between games of a White Sox doubleheader, asked fans to bring disco records, which would be demolished in an explosion and ensuing bonfire on the field.

It was a release of pent-up frustration and a wild-eyed effort to rid the world of the scourge of disco, which many listeners felt had displaced rock with plastic rhythms, as Osvaldo Oyola discussed in a 2010 SO! post “Ain’t Got the Same Soul,” a discussion of Bob Seger, who famously sang in 1979, “Don’t try to take me to a disco/you’ll never even get me out on the floor.” Excited, drunk defenders of the “rock canon” rioted around the fire. The nightcap was cancelled.

These are the subjects who invest in lists.

Many who witnessed the event, both in person and on television, experienced its personal, racially charged, and violent implications. Aspiring DJ Vince Lawrence, who worked as an usher at the Disco Demolition Night game, was later interviewed for a BBC documentary entitled Pump Up the Volume: The History of House Music: [see 9:00-10:15 of the clip below]:

It was more about blowing up all this ‘nigger music’ than, um, you know, destroying disco. Strangely enough, I was an usher, working his way towards his first synthesizer at the time, what I noticed at the gates was people were bringing records and some of those were disco records and I thought those records were kinda good, but some of them were just black records, they weren’t disco, they were just black records, R&B records. I should have taken that as a tone for what the attitudes of these people were. I know that nobody was bringing Metallica records by mistake. They might have brought a Marvin Gaye record which wasn’t a disco record, and that got accepted and blown up along with Donna Summer and Anita Ward, so it felt very racial to me.

Lawrence notes that blackness was, for rock’s canonizers, part of a mostly inseparable bundle of otherness that also included queer people, among others. Although the disco backlash is often regarded as mainly homophobic, in fact it points to even deeper reservoirs of resentment and privilege.

When music companies decided to mass-market the black, queer sound of disco, they first called it “disco-rock”; two words that American audiences eventually ripped apart, or demolished, perhaps. Black and queer people—and women too, of all races and sexualities—represented the hordes outside of rock’s new citadel, whose walls were made from the Beatles’ cheeky jokes, Mick’s rooster-strut, Robert Plant’s cucumber cock, and Elvis’s hayseed hubris.

Little Richard, for example, was black and queer like disco; what to do with him? His drummer invented the straight eight rhythm, perhaps the genre’s most enduring motif. Here’s Little Richard was rock incarnate, total frenetic energy; Richard’s brilliant, singular approach to the piano would launch a thousand rock tropes in imitation. But in canonization he could only be the nutrient-rich soil of rock—say, #36 on a best-of list—never its epitome, somehow.

I don’t know if Prince—a lifelong resident of Minneapolis, who came of age in the volatile Midwestern American milieu of white disco demolitions AND underground black electronic music culture—cared to consider this history, but he floated in it. He effectively signified on Little Richard not so much by quoting his music (though he owed a debt to him just like everyone who played rock), but by reproducing his position in the music industry. He was a queer noncomformist, never in the business of explaining himself, obsessed with control, whose blackness became a way of not flinching in the face of an industry that would never embrace him, anyway.

![]()

I interpret Prince’s musical personae as queer, not in the sense of inversion, as the anti-disco folks had it, but as a forever-exploration of sexual life. Prince’s queerness was not, strictly speaking, like Little Richard’s, but Prince took it on as an artistic possibility nonetheless. If Richard dwelled on this particular fringe as a consequence of his body, his desires, and the limits of social acceptance and religious conviction, Prince chose it as his identity. But Prince also lived and worked within limits of morality and, also like Little Richard, religion.

Image by Flickr User Ann Althouse, 2007

Touré writes in a New York Times obit of Prince’s “holy lust,” the “commingling” of sexuality and spirituality. Jack Hamilton writes of the doubt and moral uncertainty that coursed through songs like “Little Red Corvette.” Holy lust is arguably the central pursuit of rock; the term “rock and roll” is etymologically linked either to intercourse or worship, appropriately, emerging in both cases from African-American vernacular. Prince’s queer play with sex, sexuality identity, and religion is as rock and roll as it gets.

![]()

As punk sputtered, Simon Reynolds writes in Rip it Up and Start Again, funk appeared to rock fans as a racially tinged, politically and sexually charged savior. Bass, the heart of funk, was key to punk becoming post-punk around 1980. The instrument was suddenly charged with new symbolic and structural importance. During the same period, it is remarkable how many of Prince’s songs either have no bass, or rework bass’s role entirely. “When Doves Cry,” from Purple Rain (1984), Prince’s 6th studio album, is the best-known example of an ultra-funky track that withholds bass entirely, but “Kiss” lacks it, too, as well as “Darling Nikki.”

Earlier on Purple Rain, the bass on “Take Me with U” plays almost as a drone, buzzing like a minimalist’s organ.“Kiss,”from 1986’s Parade and Prince’s second-biggest hit —yet only #464 on the Rolling Stone list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time—is so tight, so locked in, so populated by alluring timbres that suggest an alien plane of instrumentation, that you forget it’s even supposed to have bass by rock top 40 convention. On much of 1980’s Dirty Mind, it is difficult to know which carefully tweaked synthesizer tone is supposed to index the bass, if any. Prince’s funk was even funkier for being counterintuitive, as Questlove notes. This gesture wasn’t rejection, of course, it didn’t “transcend” funk. Prince was still playing inarguably funky music, and the lack of bass is so unusual that it’s almost even more apparent in its absence. Free, but not too free.

![]()

Prince approached rock iconicity much as he approached bass, which is to say that he embraced clichés, but performed them inside-out, calling attention to them as both limits and possibilities, as constraint and freedom. “Raspberry Beret,” from 1985’s Around the World in a Day, is a boppy “girl group” song with sly allusions to anal sex, that uses exotic instruments and is written in an obscure mode. The virtuosic riff on “When Doves Cry,” instead of going where guitar solos go, comes right at the beginning of the track, before the drums, both seemingly isolated from the rest of the song and yet heralding it, too.

All of this worked very well, of course. His songs are just idiomatic enough to give listeners a foothold, but brave enough to evoke a world well beyond idiom. In retrospect, this is precisely what Little Richard had done. This is also what Hendrix and George Clinton and Tina Turner and OutKast have done, from where they rock out—way beyond the citadel, mastering many idioms, then extending them, at once codifying and floating away from genre.

Andre 3000 of OutKast rocking outside the box at Lollapalooza 2014, Image by Flickr User Daniel Patlán

Prince’s career calls back to the personal and artistic concerns, as well as the innovations, of Little Richard and other artists’ sonic expressions of blackness that both built rock’s house and sounded out the tall, white walls of the citadel that would exclude them. All of these artists, I suspect, find little point to hanging out near the citadel’s gates; there are other, funkier places to live. Prince himself was perfectly comfortable working athwart Warner Brothers, the press, stardom. He did more than fine.

We are free to interpret Prince, but not too free. Creative as he was, he lived in his time; he was no alien. The greatest testament to his genius is not that he escaped the world, nor that he rendered a new musical landscape from scratch, but rather that he worked in part with rock’s sclerotic structural materials to create such beautiful and fluid work.

—

Featured Image by Peter Tea, July 12, 2011, under Creative Commons license No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0)

—

Benjamin Tausig is assistant professor of ethnomusicology at Stony Brook University, where he works on sound studies, music, and protest in Bangkok and other urban spaces. He is on Twitter @datageneral

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Enacting Queer Listening, or When Anzaldúa Laughs–Maria Chaves

Learning to Listen: The Velvet Underground’s “Once Lost” LPs–-Tim Anderson

Music Meant to Make You Move: Considering the Aural Kinesthetic-Imani Kai Johnson

Black Mourning, Black Movement(s): Savion Glover’s Dance for Amiri Baraka–Kristin Moriah

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments