DIANE… The Personal Voice Recorder in Twin Peaks

READERS. 9:00 a.m. April 2nd. Entering the next installment of SO!’s spring series, Live from the SHC, where we bring you the latest from the 2011-2012 Fellows of Cornell’s Society for the Humanities, who are ensconced in the Twin Peaks-esque A.D. White House to study “Sound: Culture, Theory, Practice, Politics.” Enjoy today’s offering from Tom McEnaney, and look for more from the Fellows throughout the spring. For the full series, click here. For cherry pie and coffee, you’re unfortunately on your own. –JSA, Editor in Chief

“I hear things. People call me a director, but I really think of myself as a sound-man.”

—David Lynch

From March 6-April 14 of this year, David Lynch is presenting a series of recent paintings, photographs, sculpture, and film at the Tilton Gallery in New York City. The event marks an epochal moment: the last time Lynch exhibited work in the city was in 1989, just before the first season of his collaboration with Mark Frost on the ABC television series Twin Peaks. At least one painting from the exhibit, Bob’s Second Dream, harkens back to that program’s infamous evil spirit, BOB, and continues Lynch’s ongoing re-imagination of the Twin Peaks world, a project whose most well known product has been the still controversial and polarizing prequel film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.

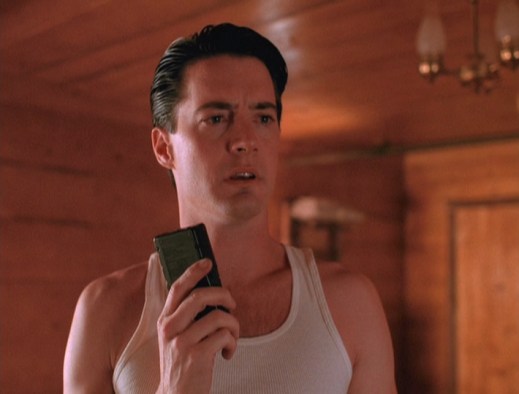

These forays into the extra-televisual possibilities of Twin Peaks began with the audiobook Diane…The Twin Peaks Tapes of Agent Cooper (1990). An example of what the new media scholar Henry Jenkins and others have labeled “transmedia storytelling,” the Diane tape provided marketers with another way to cash in on the Twin Peaks craze, and fans of the show a means to feed their appetite for FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper, aka Kyle Maclachlan’s Grammy nominated voice praising the virtues of the Double R Diner’s cherry pie.

Based on the reminders Cooper recorded into his “Micro-Mac pocket tape recorder” on the show, the cassette tape featured 38 reports of various lengths that warned listeners about the fishy taste of coffee and wondered “what really went on between Marilyn Monroe and the Kennedys.” As on the program, each audio note was addressed to Diane, whose off-screen and silent identity remained ambiguous. For the film and audio critic Michel Chion, Diane is an abstraction, or the Roman goddess of the moon. Others claim “Diane” is Cooper’s pet name for his recorder. The producers delivered their official line in the 1991 book The Autobiography of Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes, “as heard by Scott Frost,” (the brother of Lynch’s co-creator), where Cooper says, “I have been assigned a secretary. Her name is Diane. I believe her experience will be of great help.”

Whatever her identity, on the show Diane became the motive for Cooper’s voice recordings, and these scenes laid the groundwork for the audiobook. However, unlike the traditional audiobook, which reads a written text in its entirety, Cooper’s audio diary cuts away parts of the story, and includes additional notes and sounds not heard on the show.

The result is something like a voiceover version of Twin Peaks. And without the camera following the lives of the other characters, listeners can only experience the world of Twin Peaks as Diane would: through the recordings alone. Strangely, the inability to hear anything more than Cooper’s recordings opens up a new dimension: even as eavesdroppers we come closer to understanding Diane’s point of audition, the point towards which Cooper speaks in the first place.

Back on the show, Cooper’s notes to Diane track his movements as he tries to solve the mystery of who killed the Twin Peak’s prom queen Laura Palmer. Strangely—and not much isn’t strange in Lynch’s work— in some sense this mystery has already been solved by the show’s second episode, where Laura whispers the name of her killer to Cooper in a dream.

.

.

However, Laura’s whisper remains inaudible to the audience, and Cooper forgets what she said when he wakes up in the next episode. Much of the remainder of the program, full of Cooper’s reports to Diane, was spent trying to hear Laura’s voice. Thus, Diane, the off-screen and silent listener, became the narrative opposite to Laura, whose prom queen photograph closed each episode, and whose voice became the show’s central fetish object. Moreover, this silent relationship changes how the audience hears Cooper’s voice. Rather than a chance to relish in its sound, Cooper makes his recordings because of Laura’s voice from the grave, and directs them to Diane’s ears alone. In other words, Cooper and his recordings become a conduit to Laura/Diane rather than a solipsistic memoir about his time in Twin Peaks.

This triangulation becomes more obvious, if no less complicated in a typically labyrinthine Lynchian plot twist. As I mentioned, the Diane tape makes Cooper’s reports into a kind of voiceover. Critics have interpreted them as a parody of film noir, a genre whose history Ted Martin argues in his dissertation is defined by the relationship between voiceover and death: “Noir’s speaking voice moves from being on the verge of death to being in denial of death to emanating immediately, as it were, from the world of the dead itself.” Fascinated by this history, Lynch tweaks it through the introduction of a mina bird, famed for its capacity to mimic human voices. Discovered in a cabin at the end of episode 7, season 1, the police find the bird’s name—Waldo—in the records of the Twin Peaks veterinarian, Lydecker. The combined names—Waldo Lydecker—happen to identify the attempted murderer of Laura Hunter responsible for the voiceover in Otto Preminger’s classic noir film Laura (1944). On Twin Peaks, Cooper’s voice-activated dictaphone records Waldo the bird’s imitation of Laura Palmer’s last known words, which also happen to be Waldo’s last words, as he is shot by one of the suspects in Laura’s death.

If we follow this convoluted path of listening, we can trace a mediated circuit—from Laura to Waldo to Cooper’s voice recorder—which locates the voice of the (doubled) dead in the Dictaphone, thereby returning that voice to its noir origins in another classic of the genre: Double Indemnity (1944) (see SO! Editor’s J. Stoever-Ackerman’s take on the Dictaphone in this film here). More than a mere game of allusions, this scene substitutes Cooper’s voice with the imitation of Laura’s voice, inverting the noir tradition by putting the victim’s testimony on tape. And yet, while Waldo tantalizes the audience with an imitation of the sound of Laura’s voice, it ultimately only reminds the listener of the silent voice: Laura’s voice in Cooper’s dream.

The longer this voice remained out of range of the audience’s ears, the more it produced other voices—from Cooper’s recordings to Waldo to the dwarf in the Red Room.

Eventually, however, the trail of tape and sound it left behind ended with the amplification of Laura’s whisper, which became as much the “voice of the people” as Laura’s voice. After all, ABC instructed Lynch and Frost to answer the show’s instrumental mystery (“Who killed Laura Palmer?”) because of worries about the program’s declining ratings 14 episodes after Laura’s first inaudible whisper. The audience’s entrance into the show through the mediation of marketers mimicked the idea behind the Dianetape, but with a crucial difference: now the audience tuned in to hear their own collective voice, rather than to hear what and how Diane heard. Laura’s audible voice was audience feedback. It was the voice they called for through the Nielsen ratings. The image of her voice, on the other hand, was an invitation to listen. And Cooper’s voice-activated recorder, left on his bedside, placed in front of Waldo, or spoken into throughout the show remained an open ear, a gateway to an inaudible world called Diane. Although critics and Lynch himself have compared the elusive director to Cooper, perhaps its Diane who comes closest to representing Lynch as a “sound-man.”

David Lynch, August 10, 2008 by Flickr User titi

—

Tom McEnaney is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Cornell University. His work focuses on the connections between the novel and various sound recording and transmission technologies in Argentina, Cuba, and the United States. He is currently at work on a manuscript tentatively titled “Acoustic Properties: Radio, Narrative, and the New Neighborhood of the Americas.”

The Specialty Record Shop

Harold Kelley holds "Blue Danube," a 78 record. Single 78s are visible on the rack below. Behind him is the store's soundproof listening booth. Circa 1949.

In 1947, my grandparents converted a room connected to their small home in downtown Richmond, Indiana, into a record shop. According to my grandmother, my grandfather—perhaps enamored with the family’s new “Airline” table model automatic phonograph (purchased from Montgomery Ward the year before)—somehow managed to persuade her, my great aunt Ina, and my great uncle Henry to embark on the venture. On May 12, 1947, the Monday after Mother’s Day, the Specialty Record Shop opened its doors. It would become the first black owned and operated retail establishment in the area to serve both black and white customers. (The store closed in 1980.)

Many years later, so many things strike me about this ambitious undertaking. Mostly, I realize that their actions were, particularly at that time, a very bold step across a profoundly demarcated color line in American life and music, even in Richmond, which was, with its Quaker history, somewhat more tolerant of African Americans. While Richmond’s public schools had been integrated by 1947, official segregation in the City of Richmond didn’t end until 1965. Long after my mother graduated from high school (1957), blacks and whites lived mostly separate lives—and listened to different music.

This seems especially true in the early days of the shop, although among the nearly 100 78 rpm, ten-inch breakable shellac records that comprised the store’s first inventory were records by Nat King Cole, who by 1947 had himself made it across the color line into popular music. For the week ending January 3, 1947, King Cole’s “I Love You (For Sentimental Reasons)” was among Billboard’s top ten “Honor Roll of Hits,” a tabulation of the most popular tunes in the nation. Other popular songs carried by the shop on opening day were Alvino Rey’s “Near You” and Tex Williams’s “Smoke! Smoke! Smoke! (That Cigarette).”

.

Specialty would come to distinguish itself from its five Richmond competitors by carrying all kinds of music and special ordering any sound a customer wanted: classical, country and western, bluegrass, jazz, R&B, spiritual, folk. Music that other stores didn’t stock, Specialty carried, and its inventory eventually included more than 400 different labels. White customers who listened to sounds outside of mainstream popular music of the day found a home at Specialty, but on occasion would still feel the need to discreetly whisper their requests for the latest country and western or bluegrass hit, as if embarrassed by their own musical tastes. Such was the climate in those early days.

.In the 1950s, the Specialty Record Shop, which had from its inception boasted the “Greatest Variety in Recordings,” was in its advertisements not only marketing all genres of music but also both white and black musicians. A November 24, 1954, advertisement, for example, promotes Specialty’s wide variety of “albums and single records of popular, children’s, classical, religious, western, rhythm and blues, and jazz.” And an earlier advertisement from May 19, 1954, for example, promotes Tommy Dorsey (“Little White Lies”), Artie Shaw (“Special Delivery Stomp”), Fats Waller (“Honeysuckle Rose”), Duke Ellington (“Solitude”), Jimmie Lunceford (“Jazznocracy”), and Coleman Hawkins (“Body and Soul”).

A "Tips on Tops" Specialty advertisement promoting music by Perez Prado, Sarah Vaughn and Dinah Shore, Johnny Desmond, Les Baxter and Roy Hamilton, and Sauter-Finegan. This ad also features Specialty's outlet store in Connersville, Indiana. Richmond Palladium-Item, May 11, 1955.

Still, what’s painfully clear from the majority of advertising during that time is that mainstream music of the day reflected “popular” (that is, white) tastes. While black teenagers like my mother listened to “Ain’t That a Shame” by Fats Domino, her white counterparts listened to “Ain’t That a Shame” by Pat Boone. On and on, two versions of records—black and white—and two audiences: Among black songs covered by white artists that my mother remembers from her youth (most certainly carried in my grandparents’ store in both incarnations) are “Fever” by Little Willie John and “Fever” by Peggy Lee, “Long Tall Sally” by Little Richard and “Long Tall Sally” by Pat Boone, “Good Night, Irene” by Leadbelly and “Good Night, Irene” by the Weavers, and “Hound Dog” by Big Mama Thornton and “Hound Dog” by Elvis Presley.

.

Marilyn Kelley, fifteen, helping customers with Henry Bass and Harold Kelley at the Main Street shop, 1955.

The R & B sounds that my mother, Marilyn Kelley, favored in musical artists in the 1950s were the familiar sounds of (or “sepia” as it was called early on), gutbucket, and melisma—black musical sounds and pronunciation not acceptable to the parents of white teenagers (although white youth were of course becoming familiar with these sounds). Covers changed that sound and made popular rhythm and dance music acceptable to white parents while satisfying white teens and keeping them “inside the fold.” White people (and black people) regularly heard and saw Dinah Shore, Peggy Lee, Pat Boone, Elvis Presley, and other white performers on radio and television, as the record companies heavily promoted these artists and their versions of popular songs. Black performers, on the other hand, were much harder for black people (or everybody else, for that matter) to discover. In the Midwest you had to catch Randy, a white disc jockey out of Nashville, who played black performers’ records and sold them through mail order (see WLAC—Radio). My mother listened to Randy’s show from her bedroom nearly every Saturday night.

.

I had never heard of Little Willie John or his version of “Fever” until my mother mentioned it, but when I listened to his voice for the first time I immediately understood what compelled my parents as teenagers to desire this song, even without lots of radio play or the benefit of television. When I sent my mother a link to Gayle Wald‘s review of a book about the musician (Fever: Little Willie John: A Fast Life, Mysterious Death and the Birth of Soul), she remarked that as a young girl in the rural Midwest she knew not a single thing about him except for the sound of his voice on that one song, which has stuck in her memory all these years. Few people in rural America knew what budding black artists looked like in those days. For listeners like my mother it was all about sound because there was practically nothing else. Pure sound drove her to enjoy these artists and made her want to hear their music again and again.

Into this world jumped two ordinary black couples, moved by their own phonograph player and records to turn a space they had leased to a succession of black beauty parlor operators into a small storefront: Harold Kelley, my grandfather, a carpenter by training who tended as carefully to the foundations of the store as to its customers; my grandmother, Elizabeth, who handled the register and advertising; my great aunt Ina, who mostly worked behind the scenes as the bookkeeper; and my great uncle, Henry Bass, known among the family as “the promoter,” likely as much for his knowledge of music, particularly jazz, as for a habit of walking up and down the street talking to people (a young African-American man named John would join the four after first lingering in the shop as a customer, then helping as a volunteer, until finally becoming an invaluable employee in 1955.)

Kelleys and Basses: Left to right: Henry Bass, Mary Ina Bass, Elizabeth Kelley, and Harold Kelley, co-owners of the Specialty Record Shop, circa 1963.

Benefiting first from their proximity to downtown at 611 South A Street, beneath a rose-colored neon sign, and later in the more spacious Main Street shop—with its “high fidelity” room in the basement—that I remember, the Kelleys and Basses managed to put several other record stores out of business, but more significantly they forged a small community—white and black—around music at the heyday of a vast industry and at one of the peaks of cultural segregation, which even now, so many decades later, seems like no small accomplishment.

Last year, my mother and I traveled to Richmond to visit both Specialty locations, maybe thinking that in all their metaphorical glory they would inspire us to write down what we remember. We went first to the storefront on Main Street, the place that I knew, and then to the small frame house on South A Street, the early shop and my mother’s childhood home. The drabness of the place knocked any hint of nostalgia out of both of us: The bushes and flowerbeds were gone, and the building looked cold and empty, slightly seedy, and a little miserable—these days no doubt valued more for the land it sits on than for the property itself. Thinking now of how my mother must have felt to see her childhood home diminished so mercilessly by time and progress still pains me.

She said then and I write with certainty now that it was more than it looked, which brings me back to what Specialty was, which must be something larger than what stands in our memories or I would not be writing this. It is difficult to attach particular significance to the place in a simple essay about music except to say that as with sound with Specialty meaning was everywhere, and as with music, Specialty reached everyone, at least in Richmond. Its soundproof booth, five-by-five feet square, drew high-fidelity enthusiasts to listen longer than perhaps should have been allowed. A single door connecting the store to my grandparents’ home, sometimes left open by chance, invited curiosity and even boldness from some customers who, stumbling upon the family’s dining room table with its treasure trove of uncataloged records may well have lingered too long in a private space but were never scolded or turned away. The record company representatives who, swept up in the excitement of Specialty’s open house in 1955, began helping customers buy any record, regardless of its label. Taken together, these shared experiences become a narrative of human experience as intricate and complicated as music itself, not so unlike the tapestry of sound that compelled my mother to listen to the magnetic voice of Little Willie John.

In the musical amalgam of today, it is at times difficult to imagine an America so rural, isolated, and segregated, at least in these particular ways. These days “black” music—that is, music by African-American performers—is likely more accepted by and certainly more fully integrated into mainstream America than is the black population itself. Virtual musical communities like turntable, Spotify, Grooveshark, and Pandora are as much growing purveyors of music as are iTunes and Amazon, the new corner record stores, and as such hold much promise for unprecedented global musical cross-pollination and exchange.

As we may rightly celebrate the cultural integration of more sounds into a larger and perhaps more democratic musical landscape, it is also appropriate to mourn the passing of brick and mortar record stores (and bookstores and libraries, too, I might add) like Specialty, as much for their fidelity as for the ephemeral things these spaces once contained: qualities that bring kinship and serendipity to human experience—sound, yes, but also light, smell, touch, and color, with all its complications.

As we may rightly celebrate the cultural integration of more sounds into a larger and perhaps more democratic musical landscape, it is also appropriate to mourn the passing of brick and mortar record stores (and bookstores and libraries, too, I might add) like Specialty, as much for their fidelity as for the ephemeral things these spaces once contained: qualities that bring kinship and serendipity to human experience—sound, yes, but also light, smell, touch, and color, with all its complications.

—

Jacqueline Dowdell received a B.A. from the University of Michigan and an M.F.A. from Cornell University. She is a communications coordinator at Cornell Law School. Thanks to her mother’s memories, her grandmother’s meticulous archive of Specialty history, and a newfound enthusiasm for sound, she is working on a memoir about the Specialty Record Shop.

.

Recent Comments