Aural Guidings: The Scores of Ana Carvalho and Live Video’s Relation to Sound

If you were to choose to watch live video composer and performer Ana Carvalho’s work silent, your brain would be easily guided into a synesthetic experience, assigning sounds to each rhythmic change in color, pace, frame. Her images oscillate…they dance, they breathe. As you experience this, there might be a sense that you have lost your ability to hear the outside world, as these images are clearly attached to, woven with, a part of sound.

There is a history of composers such as Iannis Xenaxis and Cornelius Cardew using graphic scores and notation in place of traditional methods and symbols, as a way to reach a deeper expression through allowing greater interpretation, chance, and improvisation with their musicians. They concentrate more on conveying information on how a work is played, rather then what notes to play when. Carvalho uses the graphic score much in the same way, but also as a method of communication between live audio and live video performances, instructing a dialog between two disciplines that are often side-by-side or leaning on each other, but rarely woven together in the manner I have experienced both as audience, and as an audio composer, with her work.

The following interview has been edited for style.

Maile Colbert: Hi Ana, how are you today? And what are you working on currently?

Ana Carvalho: I am good. I’m working on a performance to present at the solstice, with Neil Leonard, and a text about the possibility of expansion of the mind through performing and fruition of being in an audiovisual performance.

At the moment the performance is still involved into misty possibilities of what we know of each other’s work, and what we have been developing individually and talking about. There will be saxophone, electronics, and visuals made of strange landscapes.

MC: At this stage in the process, when working with a sound maker such as Leonard, how do you think about the images’ relationship with the sound?

AC: Images come to be as they appear on the screen in two ways: first there is the introspection about what have I learned from the previous performances, what I want to explore further and what I don’t want to repeat. Secondly, there is the encounter with the other person and his or her work and how do I translate their sound into moving image. At some point my ideas change through the exchange and becomes something else, a visual performance that could only be presented with that sound, with that person, at that place and time.

Regarding the sound in particular, sometimes I propose a structure, or a score, to be followed by sound and image. Other times it is improvised. As I enjoy very much the process, I tend to like to make structures for the performances, which develop along drawings and texts.

MC:  Your scores of text and image are quite beautiful, and of course I am personally lucky to both have some of the published ones, and have had a chance to work with them as well.

Your scores of text and image are quite beautiful, and of course I am personally lucky to both have some of the published ones, and have had a chance to work with them as well.

As a sound maker, I find they have a flow and almost narrative that feels both intentional and intuitive, no matter how abstract. When you make these, how much of a clear idea of how the audio would sound in relation to the images is in your mind? Do your images always or often follow the same score? Do the results surprise you?

AC: My state of arriving at the point of starting to make a composition is very much the same I described about working with a sound artist towards the presentation of a performance, that is, what do I want to develop further and what I want to leave behind? Then, what is particular to this new situation/performance/collaboration? The composition is a sort of a vehicle that connects process and performance, and that connects sound and image.

The composition is for the two mediums, sound and image, and they are considered in terms of composition as a unity made of two parts. They have to work in a conversational way. Imagine two close friends and how they would be talking to each other. I have in my imagination how it would be ideally two people in that position. That is how sound and image relate on the composition. I think in the most generic terms, more of intensity and flow rather than sonic results. For this reason any musician, with any possible (or invented) instrument, with whichever image or sound database, is able to play a score. It’s required though that the performers take time to reflect, that the composition is understood and incorporated in the way each one plays their instrument. The results are always a surprise.

MC: What inspired you to start working in this way with the scores, and when?

AC: My interest in making compositional scores, and from them documents related to my performance, has been inspired by conceptual and process based art and by my research on documentation of the ephemeral. The focus on the process highlights the need for other representations that are not the finished art object per se. These other ways of representation use available media to describe the making and the reflection while making. Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973-79) is a very interesting example of what I am describing. She is expressing her feelings, the growing process of a child and an external perspective through visual objects displayed both as an exhibition and in book formats. Within audiovisual practice, I have been researching for the past five years on creative ways to make documents of the process. My attention was directed to composition in music. The influence of the composer Cornelius Cardew has been great, especially his work Treatise and his idea of directed improvisation. John Cage was also very important for his structures (in talks, texts and music), the use of the I Ching, and for bringing chance into composition.

Simultaneously, while studying and reflecting on these and other subjects, I realized that intuitively I make drawings, texts, and take photographs as a way to detach from the everyday and immerge into a creative process which eventually will lead to the concept and content of a performance.

Systematic Illusion – The Subtle Technique in an Earthquake Detector Construction has been so far the most complex project to include a score, as well as a series of photographs and the performance. It was presented in its complete form just once in the curatorial project Decalcomania. Organizing these elements as composition, creating a score, and from all this to make little books has been a way of putting into practice my research interests.

Systematic Illusion – The Subtle Technique in an Earthquake Detector Construction has been so far the most complex project to include a score, as well as a series of photographs and the performance. It was presented in its complete form just once in the curatorial project Decalcomania. Organizing these elements as composition, creating a score, and from all this to make little books has been a way of putting into practice my research interests.

A result from the construction of the score has been that the process doesn’t stop with one performance, as I then use the same scores to perform with different artists. For example with the score from this project I created the Earthquake Detector performance series within which we presented the performance together in São Paulo in 2013 at the event Arranjos Experimentais.

MC: As you speak about your work, I keep thinking about Robert Bresson’s Notes on Sound and how most of his notes refer to variations of not letting sound or image take over each other, but to weave them together within the composition. In his Notes on the Cinematographer, he also wrote number “10. not to use two violins when one is enough”. What might this mean to you in relation to your collaborations?

AC: One very inspiring event in the attempts I make to construct a formal grammar and way for me to address collaborations has been to see the film Passage Through: A Ritual by Stan Brakhage. The film was screened at Serralves Museum, here in Porto, Portugal, in June 2011. The event addressed the collaboration and improvisation of music in relationship with cinema from the work of the composers Malcolm Goldstein and Philip Corner and their music in the film work of Daïchi Saïto and Stan Brakhage.

The most amazing thing in Passage Through: A Ritual was to watch such a beautiful film made of an abundance of black screen, that is, an absence of visual form, of light and movement. Each appearance of image was a precious moment. What I learned is that the visual emptiness, and sonic as well, contains information when stimulated through glimpses of image, making the experience of seeing and listening very deep. (In his Notes), Bresson sums up this appropriateness of means and complex connections in a simple and clear sentence.

On the scores I make most of the information can be used for both sound and image. On the Refractive Composition, the scale of greys is for image. That was its purpose when the score was performed the first time. But if someone decides to play from the score without knowing anything about it beforehand, and lacking this intention (which was relevant when it was made, but afterwards there was the decision to not leave it as a declared instruction), that person can also interpret the same information as sound.

MC: Alchemy has been described as: “…the chemistry of the subtlest kind which allows one to observe extraordinary chemical operations at a more rapid pace; ones that require a long time for nature to produce” (Paul-Jacques Malouin, Alchimie). Looking from a history of cinema, there is a tradition and pattern of picture coming before sound, a hierarchy that is both in process and production. You often feel this as an audience. Your work and collaboration have a quality of sound and image having been born together. Having worked with you using your scores, I was likening it to being given a recipe where you have before you ingredients and suggestions, but there is room for your own improvisations and reading. Perhaps that is where that feeling of both disciplines coming together in a manner that feels like they are one part of a whole, rather then separate but leaning on each other, comes from.

Is there an alchemical element to this work, or are you seeking one out? And in that regard, are your scores like a recipe?

AC: What I am seeking with my work can relate to alchemy as experiments and attempts in the quest for depth in all things at the point where differences and frontiers become undefined and irrelevant (in communication between beings, in areas of knowledge, between matter and energy). This quest for depth is based on stubborn curiosity towards evolution as a person, and as part of the world. Perhaps there isn’t an alchemical element to the work, but rather a connection with alchemy, in the ways scores relate to the experiments as recipes to be shared with others in construction and change. This takes me to another aspect of composition. It is difficult for me to understand live image as just accompaniment to a music performance, and vice versa. This is perhaps central to my composition, and the reason why I am doing it for sound and image, to be able to perform that intertwined.

If we look at compositions as recipes, it aim will be to set the performers in tune with each other in the construction of a performance, to set sound and image in dialogue, and to permit a multisensory experience. I have been trying to get other artists interested in performing my scores. To perform from another artist’s score may be very common in music but is unheard of in live visuals. I have as an objective to make a change in that, but for now I perform the scores with sound artists. With the Earthquake Detector series I asked sound artists to read from the score and perform with me. So far, I have presented this as performance with Jeremy Slater, Ben Owen, and with you. Because each artist has a very different approach to the score and reads it in its own way, the processes have been very different. For example, Ben Owen made visual reinterpretations of the structure, and you experimented with and without voice (reading of the text in the score), the results are therefore equally different.

MC: Aside from your scores, you could speak about your relationship to the sound you work with, and sound makers you work with, in the live moment of performance?

AC: Looking for a sound artist to work together on a specific piece or to interpret with me a composition comes from a need to transcend my individual perception of the world and to perceive it with others. It is, again, the curiosity to know the world. The only time I made a complete sound piece on my own was for the performance Vista II – Montanha presented last May (as part of Semana Andrómeda, in Maus Hábitos, Porto). Aside from this really interesting experience, each collaboration is different, every process is different, because each musician is a different person with different skills and sees the relationship between sound and image in different ways.

I am very thankful for everything I have learned with each collaboration and all the intensity with each performance but, as always, it’s the curiosity and the need to explore new frontiers that makes me move from previous project to next project. It is also the possibilities that intuitively present themselves as challenges and the “what if…” in variations.

—

Ana Carvalho is a live video composer and performer, and writes on subjects related to live audiovisual performance. She is a doctor of Communication and Digital Platforms from FLUP (Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto). Her thesis is “Materiality and the Ephemeral: Identity and Performative Audiovisual Arts, its Documentation and Memory Construction.” Currently, she holds a position as invited lecturer at the ISMAI (Instituto Universitário da Maia). For more on her work, visit: http://cargocollective.com/visual-agency/About.

—

Maile Colbert is a multi-media artist with a concentration on sound and video who relocated from Los Angeles, US to Lisbon, Portugal. She is a regular writer for Sounding Out!

—

All images courtesy of the author.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Playing with Bits, Pieces, and Lightning Bolts: An Interview with Sound Artist Andrea Parkins — Maile Colbert

Sound as Art as Anti-environment — Steven Hammer

Live Electronic Performance: Theory and Practice — Primus Luta

Sonic Connections: Listening for Indigenous Landscapes in Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles

In April 2015, ten American Indian extras walked off the set of Adam Sandler’s new film The Ridiculous Six, a spoof on the classic Magnificent Seven (1960), in protest over the gross misrepresentation of Native cultures in general, and in particular over its insults to women and elders. Allison Young, a Navajo actress who participated in walking off, stated, “Nothing has changed. We are still just Hollywood Indians.” Young is referencing a long history of the film industries’ construction of stereotypical American Indians by non-natives created to entertain non-natives.

Still from the movie. From http://www.arthousecowboy.com

Within this long history exists a rare film, Kent Mackenzie’s 1961 The Exiles, re-restored and re-released in 2008 by Milestone Films. The Exiles is one of the few 20th century films that feature urban American Indians; it follows three main Native narrators from dusk to dawn as they experience the joys and struggles of urban life. Without an official score, this black and white docudrama places sound against haunting 35 millimeter black-and-white images of a downtown Los Angeles landscape. This mis-en-scène creates what Mackenzie (the white screenwriter, director and producer) asserts is “the authentic account of 12 hours.” The voiceovers of Homer Nish, a Hualipai from Valentine, Arizona who recently moved to Los Angeles after fighting in the Korean War; Yvonne Walker, originally from the White River Apache reservation in San Carlos, Arizona who first moved to the city to work as a domestic; and Tommy Reynolds, who is identified only as Mexican-Indian and is portrayed as a comedic playboy and the life of the party; narrate the intimate, day-to-day lives of urban American Indians.

From the website http://www.exilesfilm.com/

In this post, I consider what we can hear if we pay close attention to how the director incorporates the narrators in a kind of Indigenous soundscape. Mackenzie’s soundscape bring together voices as well as music. The collage of sounds traces the journeys of American Indians to and from Los Angeles in the mid-twentieth century. The sonic connections in The Exiles provide a cacophony of histories of forced movement, transit, and re-making spaces as Indigenous at the same time that it perpetuates important historical silences. I borrow Chickasaw scholar Jodi A. Byrd’s term from The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (2011), cacophony—or “discordant and competing representations” and experiences— and apply it to the sounds that inform the indigenous space represented through the film.

The narrators are part of a large population of American Indians who moved from rural reservations to urban centers after WWII. Due to the federal government’s mismanagement of Native tribes’ land and resources, and the genocidal abandonment of treaties made with tribes, the late 1950s and 1960s were times of dire economic and social conditions on reservations. The influx of Native Americans to cities also came because of assimilation campaigns in boarding schools, military service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ “Termination Era” policies (1940s –1960s) that intended to terminate the state’s bureaucratic relationships with Native tribes. Relocating Native populations from reservations into cities where work was available year-round was a key aspect of the Termination Era policies. According to Norman Klein (The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory), areas near downtown Los Angeles, including Bunker Hill where the film is primarily shot, were multi-racial neighborhoods in economic decline and therefore became relocation sites for American Indians. Importantly, both Klein and Mackenzie are silent about the prior forced removal of Tongva on that very same location that began in the 1840s.

The audio track of The Exiles contradicts the stereotypical American Indian sounds featured in Hollywood movies. The film’s contemporary mainstream Hollywood releases included sounds such as the whooping sounds of “hostile Indians” in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), the broken English spoken by the “Apache” in Delmer Daves’ Broken Arrow (1950), and stereotypes played out in John Sturges’ Magnificent Seven (1960). In the soft Southwestern Native lilt of Yvonne’s voice, the way that Homer and others add “you know?” to the end of almost every sentence they utter, alongside the rhythm of the casual banter and tenor of the men’s laughter, I hear a potential sonic archive of American Indians that talks back. For example, in a short clip when Tommy and his friends enter Café Ritz, an Indian bar, Thomas calls out over the loud rock and roll music as he passes people at the bar. Tommy shifts easily between English (“What’s happening there, man?”), Spanish (“Gracias amigo, ¿cómo estas?”), and Dine (“Yá’át’ééh. E la na tte?”). Careful attention to the cinematic soundscape provides access to voices of discontent and resiliency, practices of building and maintaining multilingual multi-tribal Indian spaces, and the flow of American Indians between reservations and multiple cities.

Understanding the sounds and the silences of The Exiles as a cacophony offers a way to appreciate how the film both perpetuates stereotypes but also provides insights into the urban American Indian experience. Mackenzie’s construction of Homer Nish and American Indian men continues a myth that it is individualized behavior that keeps Indians from the American Dream. (In his 1964 masters thesis, “A Description and Examination of the Production of The Exiles: A Film of the Actual Lives of a Group of Young American Indians” Mackenzie states outright that he believes they are responsible for the mess they created). The Exiles portrays American Indian men reading comic books, listening to rock and roll, hanging out at bars instead of working, and taking rent money away from their suffering women and children to gamble. These formulaic images of Native Americans are informed by a long history of visual, literary and legal representations of American Indians that compose Indian men as either savage, infantile and emasculated. But if we listen to the banter and laughter in the bar scenes and at home, we also hear the caring intimacy of camaradrie. The cacophony of sound provides a counterbalance to the visual representations.

The Voiceover and Realism

Mackenzie uses dialogue to direct the visual and sonic narrative of the docudrama’s soundscape. Ironically, this collaborative low budget project that stretched on for three and a half years has minimal original dialogue. They could not afford sound techs on site, so the most obvious sonic evocation of realism Mackenzie explores is asynchronous sound performed in a studio months later. In Mackenzie’s master’s thesis he writes that, to construct dialogues (they often voiced their lines with a group of people around), “people would joke around a lot” while “everybody was drinking beer” (76). The filmmaker did not find that dialogue on larger budget feature films at the time were “lifelike” and believable. He writes that people

seldom spoke of important matters directly; they seldom spoke clearly or coherently when they did speak and their everyday language was full of overlaps interruption and communications through looks, gestures and shrugs. Many sentences made the end understood. …What a person said seemed less important than how he said it. (73)

Here, it becomes clear that the “realism” Mackenzie pursues is more about a style of filmmaking rather than about an authentic rendering of Native American everyday life. If he found the actors performing lines too dramatically Mackenzie states he “would blow the scene apart by asking for more casual and apparently pointless lines” (73). He created a specially mediated recording of the people, downtown Los Angeles and the time period. In other words, he pursued realism: he did not seek to fully capture real experiences.

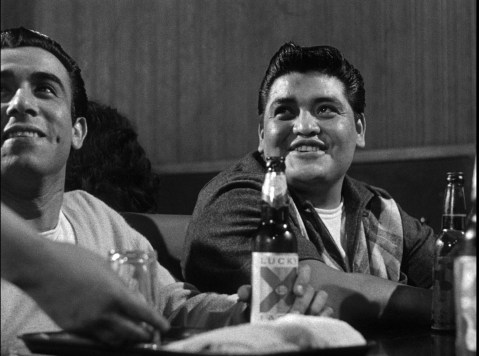

Tommy Reynolds and Homer Nish in Kent Mackenzie’s THE EXILES (1961).

Through interviews he guides the actors to talk about their everyday lives, their problems and their thoughts about life. Mackenzie used “improvised tracks” out of individual interviews in an attempt “to help preserve their point of view in the film.” He interviewed Homer, Tommy and Yvonne for several hours apiece, questioning and re-questioning them – not necessarily to document the subjects’ truths but “for emotional quality and general attitudes and feelings” (78). Despite his intentions, the voiceovers provide some context of the trials of everyday life and how the leads negotiated their belonging in a space far from home. Mackenzie’s realism builds a collage of soundscapes—voiceovers, background noise, music—to orchestrate a scene rather than simply document part of a 12-hour period of life.

Rock and Roll and Urban Indian Sounds

Mainstream “Hollywood Indians” are associated with a limited soundscape of drums and whoops, but Mackenzie’s use of contemporary rock and roll illustrates the complexity of the indigenous soundscape. Even though the film opens with the slow repetitive beating of the buckskin drums and a contextual opening monologue, after the drums stop it is the early surf music of Anthony Hilder and his five-piece band, The Revels, that drive many of the scenes. The music renders audible the many ways people tried to belong in new locations and within new cultures, juxtaposing the fast blast of the trumpet and guitar riffs of the Revels with the steady beat of the drum and shake of a turtle rattle.

Mackenzie continues this juxtaposition later in the film. Homer, alone on the street in front of a liquor store, opens a letter a bartender handed to him earlier in the evening. At the top of the letter is written “Peach Springs, Arizona” and tucked within the letter is a picture of an older man and woman. The camera focuses on the picture that dissolves and reemerges as a rural desert scene. The man from the picture sits beneath a tree with a girl and the woman, and rhythmically chants and shakes a rattle. There is no voice-over or dialogue; ceremonial singer Jacinto Valenzuela’s repeats a song multiple times without an English translation. The steady rattle of the dry seeds in the gourd are a sharp contrast to the pace of the Revels’ songs that saturates Homer’s earlier scenes.

Without guidance from a narrator, the scene is left to audience interpretation. The scene and its sounds could represent Homer’s sense of being displaced between times, or a homesick romanticized remembrance of family life: the moment quickly dissipates and Homer once again stands alone on a corner bathed in the streetlight. However, the music here could be a sonic connection that provides an alternative geography of indigenous space and place. Mackenzie’s collage of sound echoes the circuitous path of indigenous bodies and ideas of indigenous life in diasporas described in Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska scholar Renya Ramirez’s work in Native Hubs: Culture, Community, and Belonging in Silicon Valley and Beyond. The rattle and drum can instead signal a belonging to a community and people in a present that Homer carries within him. Through sound, Mackenzie connects Homer with his communities, traditions, and a sense of belonging regardless of spatial distance.

Mackenzie deepens this connection when he imbeds Homer in a place and community through the dancing and drumming on Hill X in the penultimate scene of the film sounds. When Homer talks about Hill X (formerly Chavez Ravine, then a site of the forced displacement of Mexican residents in Los Angeles in 1950-1952, now the site of Dodger Stadium) we hear his strategy for his own and his tribe’s collective survival. The shaking of the gourd in the desert and the dancing, singing and drumming of the 49 —lead by Mescalero singers Eddie Sunrise Gallerito and his twin cousins Frankie Red Elk and Chris Surefoot—shows a reclaiming of Los Angeles as indigenous land. Thus practices of sound and movement function as what Tonawanda Seneca scholar Mishuanna Goeman identifies as “remapping” of Indian space. Taken together with the beat of the drum, the bells and rock and roll compose the content of a Los Angeles indigenous soundscape.

The Exiles registers contemporary American Indians in motion. Homer and his comrades reclaim Hill X as Indian land with song and dance over a century after the City of Los Angeles displaced the Tongva out of that same location. At the time of the filming, American Indians were also forced to move within Los Angeles- their homes on Bunker Hill soon demolished and replaced by high rises. Paying attention and critically re-listening to the sounds of The Exiles offers an alternative soundscape of Indigenous life.

The Exiles registers contemporary American Indians in motion. Homer and his comrades reclaim Hill X as Indian land with song and dance over a century after the City of Los Angeles displaced the Tongva out of that same location. At the time of the filming, American Indians were also forced to move within Los Angeles- their homes on Bunker Hill soon demolished and replaced by high rises. Paying attention and critically re-listening to the sounds of The Exiles offers an alternative soundscape of Indigenous life.

−

Featured image: “chavez ravine” by Flickr user Paul Narvaez, CC BY-NC 2.0

−

Laura Sachiko Fugikawa holds a doctoral degree in American Studies and Ethnicity with a certificate in Gender Studies from the University of Southern California. Currently she is working on her book, Displacements: The Cultural Politics of Relocation, and teaches Asian American Studies at Northwestern University.

−

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #40: Linguicide, Indigenous Community and the Search for Lost Sounds–Marcella Ernst

The “Tribal Drum” of Radio: Gathering Together the Archive of American Indian Radio–Josh Garrett Davis

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies–Christine Ehrick

Recent Comments