Sounds of Home

Last month, I braved hail, snow, and just about every kind of plague-like spring weather to hear Karen Tongson’s talk at Cornell about her soon-to-be-released book, Relocations: Emergent Queer Suburban Imaginaries (NYU Press’s Sexual Cultures Series). Karen’s project remaps U.S. suburban spaces as brown, immigrant, and queer, thus relocating the foundations of both queer studies and urban studies. While not a part of the “dykeaspora” of color that Karen deftly details, I am in solidarity with the lives she traces and the soundscapes she amplifies more passionately than Lloyd Dobler with his boom box.

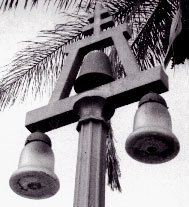

After all, Karen and I grew up together in the dusty, palm-tree lined streets of Riverside, California, meeting at Sierra Middle School and plotting our way the hell out of Dodge. . .only to later realize that our mutual plottings were really survivings—and a hell of a lot of fun—and the Riv—with its raincrosses and dry riverbeds, lifted trucks and low riders—would stay with us wherever we went.

After all, Karen and I grew up together in the dusty, palm-tree lined streets of Riverside, California, meeting at Sierra Middle School and plotting our way the hell out of Dodge. . .only to later realize that our mutual plottings were really survivings—and a hell of a lot of fun—and the Riv—with its raincrosses and dry riverbeds, lifted trucks and low riders—would stay with us wherever we went.

Since leaving Ithaca—Karen’s voice still warm in my ears like it used to be when tying up our parent’s pre-call-waiting phone lines—I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the way in which Relocations also reimagines the power of music. For Karen, music can help us know and love who we are more deeply, to enable us to “make do” with what we have been given in a way that liberates rather than incarcerates. Music is not just about “the differences it makes audible” (as Josh Kun writes in Audiotopia) but also, as Karen argues, about the ways in which sound gives us back to ourselves.

For example, a song that is spliced into Karen and I’s mutual musical DNA is “There is a Light that Never Goes Out” by The Smiths, (from 1986’s The Queen is Dead). Its various revolutions—both on turntables and in life choices—have affected us profoundly. In “The Light that Never Goes Out: Butch Intimacies and Sub-Urban Socialibilities in ‘Lesser Los Angeles,’” Karen uses the song as an affective touchstone for the ways in which sound can create “queer sociability, affinity, and intimacy” (355) while providing sonic moments of “self- and mutual-discovery” (360) and mediating relationships of place, power, pleasure, and privilege.

Karen’s ideas have since helped me understand why I used to listen to the song over and over in my lonely yet womb-like suburban bedroom, as if it were revelation and incantation. As I struggled with issues—identity and otherwise—Morrissey’s silken voice had the power to sound out the shape of my most secret wounds and simultaneously soothe them. Although I now know I am not alone in this, I thought I was back then, alone and waiting for someone to:

“Take me out tonight

where there’s music and there’s people

who are young and alive.”

In a now slightly-embarrassing Anglophilic phase—this was also around the time I was reading The Adrian Mole Diaries, watching My Fair Lady with Karen, and exchanging mixtapes with my British penpal—the Smiths were part and parcel of an England that I imagined as a long lost home. The U.K.’s pop cultural exports made it seem so much more tolerant of misfits of all kinds, let alone more temperate than SoCal for black turtlenecks and Doc Martens. At the time, I thought I was listening to difference—to the most remote space imaginable from the sweltering hothouse of Riverside—but Karen’s work reveals that I was really hearing the maudlin voice of my own longing, the jangly chords of my own desire, the oddball rhythms of my own heart.

I finally got myself to the actual England years later, thanks to the wonders of credit-card leveraged conferencing in destination locations. After the conference—at which I was, ironically, presenting on Los Angeles—I had the pleasure of spending a damp, foggy day record-shopping my way through brick-bound Nottingham. While I was gleefully flipping through velvety fields of plastic covers and comparing American imports with their UK counterparts, “There is a Light that Never Goes Out” came on the shop’s PA. With the first flare of guitar, I looked up from the record bins, startled by the warm recognition I felt at the sound of “home.”

At the time, I remember thinking that my thirteen-year-old self would be totally geeked out. However, I harbor little nostalgia for the volatile claustrophobia of my lonely tweenhood. Karen would describe my flash of recognition as “remote intimacy,” an asynchronous experience of popular culture across virtual networks of desire, a way of “imagining our own spaces in connection with others.”

Singing along for the thousandth time to Morrissey’s bittersweet grain, I realized that I wasn’t listening to my past in that record shop, but rather my thirteen-year-old self had been hearing the future in her bedroom. Dreaming of England had given her a way to grapple with the pains that ultimately produced my deepest longings: to overcome the “strange fears that gripped” me, to one day be able take myself “anywhere, anywhere,” and to feel the “light” of a love that would “never go out.”

It had taken a 5500 mile plane ride for me to realize that “home” was, in fact, a feeling of arrival rather than site of destination . . .and I couldn’t wait to get back to L.A. to give my homegirl Karen a call.

“There is a light that never goes out

There is a light that never goes out

There is a light that never goes out

There is a light and it never goes out. . .”

JSA

The Grain of the Voice or the Contour of the Ear?

One of the most exciting possibilities emerging within sound studies is the emphasis on the listener and his/her role in shaping a sound’s meaning and content. Sounds disconnected from their contexts of reception rarely answer our questions about the past, but merely make for new listening experiences in the present. Thinking with our ears is profound, but thinking through our ears can be life-changing—moving us closer to an understanding of sound’s power and its intensive connection to memory and the emotive forces of both life and death.

Until very recently, I had not heard the sound of my Grandmother’s voice in over eight years. I had actually never expected to hear it again, as she died in 2001. It is a clichéd understatement that I loved my grandmother very much; when she died, I was barely a “real” adult and I felt like we had just gotten acquainted. However, I thought I had already made peace with the passing of her beloved throaty crackle into the world of furtive dreams and spotty memory, until one night in 2004, when this loss was suddenly found.

Somewhere around two a.m. on a weekday, the phone rang. Once you are past a certain age, the shrill peal of a telephone after midnight can be downright terrifying. Someone has died. Someone is calling from jail. Someone’s life is in shreds. Nothing good. My hand hovered over the receiver for a second, as I rubbed my tired eyes and steeled myself for whatever might be at the other line.

“Hello,” I mumbled, hesitatingly.

Silence, for a second. And, then, the keen of my sister’s voice, choked through tears, “I found it.”

Inexplicably, my groggy listening ears automatically knew precisely what “it” was : an oral history of my grandmother I recorded in 1998, on teeny-tiny tapes in an itsy-bitsy recorder my sister used to record her professor’s lectures. I borrowed it, and like a good sister, I returned it. Tapes included. At the time, I thought there would be plenty more opportunities to have deep convos with Grandma. I had always assumed my sister recycled it, replacing my grandmother’s words with her bio prof’s. With three little gasped words, I realized she hadn’t.

You’d think my first reaction would be excitement—and I was thrilled, but in the nineteenth-century sense. My heart was pierced by even the thought of hearing my Grandmother’s voice again; the imagined sound tremored through me and, in a moment of pure protective reflex, I immediately cast the receiver away. In a sense, I had heard my grandmother’s ghost. The sounds magnetized on that tape seemed to resurrect her and mock the promise of that hour of conversation, when we had no idea what lay ahead.

Even though I made the conscious decision not to listen to the tape, I let the thought of her audio presence haunt me for five years. I could not escape the thought of her voice both in my memory and in this new audio embodiment. Oddly enough, I surrounded myself with pictures of my Grandmother as remembrances—cheeky 1940s shots from her youth as well as seasoned photos of us together—but those images brought me cool comfort. Their framed borders demarcated a long-gone past. When my chest got too tight, I could look away. Not so with the vibrations of her voice, which sounded out the contours of her absent body. Her voice threatened too much wonder, and with it, an attendant dose of insatiable longing. Unlike the frozen photographic slices of life, the sound had an animated heft to it. It breathed.

Ultimately, I was unable to listen to the tape through my own ears. It wasn’t until the birth of my son that I even considered playing it. Suddenly, my grandmother wasn’t mine alone, but also the great-grandmother my son would never really know. The new relation between the two of them allowed me to fashion another set of ears; I became a new listener, connected to the voice by life rather than death, by shared possibility rather than the solipsism of grief. So on a snowy night last January, I finally pressed play. With my infant son in my arms, I listened, at long last, to that beautiful crackling voice spinning stories of her childhood in Iowa and adult life in California. Ironically, I almost immediately realized there were actually two dead voices on that tape. I had long since shed the happy-but-halting girlish voice of my youth like an ill-fitting skin, but hadn’t quite realized it until I heard my old nervous laughter fill the speakers. I realized that, someday, I’ll have to introduce my son to that young woman too.

JSA

My Grandma and I talk about WWII and the sinking of the Ruben James:

Grandma Maryanne’s Interview Segment 1

My Favorite part of the interview:

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments