Playing with Bits, Pieces, and Lightning Bolts: An Interview with Sound Artist Andrea Parkins

Editor’s Note: Welcome to Sounding Out!‘s fall series titled “Sound and Play,” where we ask how sound studies, as a discipline, can help us to think through several canonical perspectives on play. While Johan Huizinga had once argued that play is the primeval foundation from which all culture has sprung, it is important to ask where sound fits into this construction of culture; does it too have the potential to liberate or re-entrench our social worlds? SO!’s regular contributor Maile Colbert interviews sound artist Andrea Parkins and gets her to talk about her creative process, and the experience of playing with sound, composition, and instruments.–AT

Editor’s Note: Welcome to Sounding Out!‘s fall series titled “Sound and Play,” where we ask how sound studies, as a discipline, can help us to think through several canonical perspectives on play. While Johan Huizinga had once argued that play is the primeval foundation from which all culture has sprung, it is important to ask where sound fits into this construction of culture; does it too have the potential to liberate or re-entrench our social worlds? SO!’s regular contributor Maile Colbert interviews sound artist Andrea Parkins and gets her to talk about her creative process, and the experience of playing with sound, composition, and instruments.–AT

—

In 2003, working towards my graduate degree in Integrated Media at California Institute for the Arts, I met and worked with a visiting artist by the name of Andrea Parkins, with whom I became a friend and colleague. Although I’ve been familiar with her work for more than a decade, every time I see Andrea perform my mind is blown. And, every time we discuss her practice, her methodology, and her thoughts on art and work, I’m always compelled and inspired in my own practice as a sound artist. In particular, I am impressed by her insights on the relationship between art, play, and the act of improvisation. The interview that follows is both a sampling of the conversations we have been gifted with throughout the years and a rare opportunity to listen in to the creative process of a working sound artist.

1. Hi Andrea, how are you today? What are you in the middle of?

I’m well – working on a number of different projects at the moment, including preparing for a residency at Q-02: workspace for experimental music and sound art, in Brussels, where I’m going to be working on a new multi-diffusion sound piece, addressing the interaction of moving objects with human gesture in idiosyncratic acoustical spaces. I’m also working on some new recordings – one is a catalogue of short pieces, combining electric accordion-generated feedback with processed field recordings; and another incorporates 15 short object-based electronic pieces into a live ensemble work.

2. Can you describe your entrance into the world of sound and music?

I grew up in Western Pennsylvania, acutely aware of the drones and sonic events in the surrounding rural landscape. At the same time my early experience of sound through my teens resided in realm of the “musical” and the social; it connoted family (nearly all of my family members were/are musicians, and music and sound was always present); culture; and musical practice as ritual. Most family members were serious classical musicians, some were rock musicians and singer/songwriters; some were both. I studied classical piano from the age of 6 through my early twenties, and from the beginning had access to and absorbed a wide range of musics– immediately attracted to dissonance, or music with subtle harmonic and timberal changes. After high school, I moved to Boston and studied jazz piano and free improvisation. In my early 20s, I bought an analog synth, and experimented with oscillators and filters, playing synth in punk, free jazz, and new wave bands. Probably most important in my sonic development was that I went to art school and in that context began making experimental films and video, drawings and installation. I believe that my exposure to non-narrative film especially had a profound effect on how I began thinking of compositional possibilities for sound, and about art that happens in time, and also space

3. Speaking of worlds, what is the line experienced, if there is one, between the experimental sound art world and improvisation? How did you find yourself with one foot in each of these worlds, and how do you navigate between them?

While I know that some artists and theorists do draw a line between sound art and improvisational “music” performance, I don’t usually think about it that way, and for the most part that is not how I experience my relationship with sound. Having said this, I recognize that there are communities that identify themselves as one thing or the other, and performance and exhibition spaces that are organized based on one side or the other of this dichotomy, so at times I do have to “navigate between them.” This isn’t necessarily a bad thing: this allows artists to build a common discourse around their particular focus, and can even develop a creative legacy among artists. For myself, I try to think about my intentions regarding a particular installation or performance: especially in consideration of site and audience, and formulate language around this that can speak to the specifics of the situation.

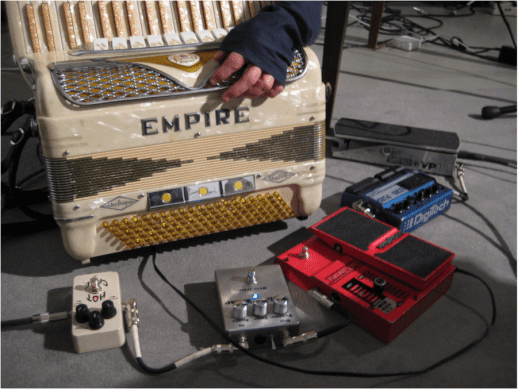

Photo Credit: Paul Geluso 2009

4. And being a woman in these worlds, have you found a difference between when you were starting out and now? Have you found a difference within the generations you work with?

I believe that for younger women, things have changed a lot: peer communities of young artists are more integrated gender-wise, and it seems that there are many more women worldwide are active and visible as experimental musicians and sound artists than when I began. I came “of age” at a different juncture and did not have this experience. To some extent this was because of the class and milieu that I came from, which meant there was no model in front of me. I do think this would have been mitigated if I had learned sooner about some of the female innovators of electronic music, among them: Bebe Barron, Wendy (Walter) Carlos, Eliane Radigue, Maryanne Amacher, Laurie Spiegel, and Pauline Oliveros. This exposure came later.

When I began working as an improvising musician, I found myself on the periphery, and never wholly part of, a group of mostly male colleagues. There were aspects to this experience that I actually now appreciate. It had value because I remained in the position of an outsider, and while I felt some sense of displacement because of this, it allowed me to develop my own critique of whatever prevailing processes and products were happening at that time, and a new assessment of what I wanted to create. I should mention that when working alone or in collaboration in other forms: intermedia, sound and performance installation, I have found that these contexts offer a more inclusive politics and discourse.

5. Something interesting came up in our last conversation that inspired me to change this question around a bit. Instead of asking you to talk about your works, and since our readers can access many different interviews, documents, and articles online, can you talk about how to talk about your work?

This is something I am learning how to do (yet again), as I become more aware that my work engages with multiple practices, multiple voices, multiple processes. It’s about beauty too (that dirty word) – in the sense that beauty (for me) is about viscerality, atmosphere, presence, fragility; this calls my attention to the physical space I am in and to how time is passing: that is to say, to mortality. Most recently I have been seeking different forms of sonic structure that are not based on “history” as forward motion, as a narrative driving through time, but that can allow for stasis, multiplicity, simultaneity, and chaos and acceptance of a potentially forward moving structure to fall totally apart.

Since 2005, in addition to exploring these modalities as an improviser and composer (for live instruments), I have been working to reintegrate a more interdisciplinary approach to my work – referencing the materiality of objects, and the body in motion, and engaging in wider range of sonic sources and processes, visual elements, and acoustical spaces. This has resulted in my creation of several fixed media works for the gallery/installation setting, as well as some electronic music pieces scored only for objects.

6. The term improvisation confuses a lot of people, and can be hard to articulate. What does it mean to you? And within improv, what does “work” and what does “play” means to you?

Speaking most simply, improvisation is (for me) a series of compositional decisions made in real time that are then immediately acted upon, with acute attention: to self, other, site and context. Being an improviser entails so much listening (to oneself and others, at the same time) and also connecting with others while maintaining one’s own sonic space/language; in a way it’s social and interiorized process at the same time. So it’s work! You are — at times – straining your ears; listening for the clues for what others are “saying,” even if they are not quite saying it. Perhaps this even involves a kind of telepathy. However, at its best moments it can be exhilarating work; there can be lively engagement among fellow performers — or when performing alone when moving among one’s own sonic materials and instruments – that is highly stimulating and fun.

Photo credit: Maile Colbert 2010

7. Is there a hierarchy of process versus presentation for you?

I often find that my best-laid plans must be jettisoned because I have an idea or epiphany that suddenly strikes me, and it just won’t wait. For me, these “lightening bolts” often quickly resolve into having to face a challenging new work process — challenging perhaps because I have been afraid that somehow it won’t produce a result that I can readily identify as successful. But the old ways will always be there, and in the meantime it is possible that by trying something else, a new discovery will come that transforms everything – including the way I think about what a “successful result” should look like. I now feel that the notion of a “successful result” in itself has become pretty relative, and in some cases, a moot point. This is because what I now define as successful can often have much to do with my assessment of the process I employ in making something, rather than how well I have fulfilled the requirements of a pre-meditated structure: the result. This has made my engagement with my work much more open-ended in a way that I have learned to appreciate over time.

For me, composition mostly happens in the editing: that is where I find (uncover, sculpt) structure from the sound that I collect and/or record, building up a mass of material from which I can “find the piece” through editing, assemblage and layering. I think this is similar to the way some filmmakers might shoot video/film and then from raw footage hone in on or discover a film’s structure via the editing process. I like the idea that instead of filling a pre-ordained structure with content one can move the content around until the structure emerges. Maybe one recognizes the completed structure when one sees it. I like to remember that a structure, even if unusual, asymmetric, messy, seemingly random, or just plain weird – if that is what emerges – is still a structure, howsoever idiosyncratic. And it can be presented.

8. Can you talk about differences between performance vs. play and performance vs. studio to you, and your relationship with the instruments you play?

In 2002, I began developing a MAX-based extended processing instrument inspired by Rube Goldberg and his machines. It has built into its programming seemingly “randomized” sonic processing that highlights and/or alters specific frequencies and densities, with emphasis on repetitions, interruptions, stasis and malfunction. When I began working with the instrument, I was exploring processes related to Fluxus in my compositional and improvisational practices. I was also thinking about a kind of poetics that I saw as related to my independent studies in feminist and psychoanalytic theory, and to the body of an improvising performer who is up against the limits of his or her own virtuosity. Once I designed the instrument I realized there really was a connection to these things – and to how approach decision-making as an artist – the importance of chance – but also slippage and failure and moments of physical awkwardness as what I try to accomplish on a technical level comes perilously (and for me, interestingly) close to falling apart – especially when performing with multiple instruments in simultaneity. My virtual instrument is a collaborative partner who doesn’t cooperate. It makes “sense and non-sense,” The slippage and failure relates to meaning, and for me is a metaphor for loss or displacement. For me, this is important … to me this is daily, everyday life.

—

Featured Image Photo Credit: Julia Berg 2010

—

Andrea Parkins is a composer, sound/installation artist and improvising electroacoustic performer who engages with interactive electronics as compositional/performative process, and explores strategies related to Fluxus’ ordered, ephemeral activities. She is a key participant in the New York sound art and experimental music scene, and worldwide she is known for her pioneering gestural/textural approach on her electronically-processed accordion and self-designed virtual sound-processing instruments. Described as a “sound-ist,” of “protean,” talent by The New York Times music critic Steve Smith, Parkins’ laptop electronics and Fender-amped accordion create sonic fields of lush harmonics and sculpted electronic feedback, punctuated by moments of gap and rift. Her work has been presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art, The Kitchen, Diapason, and Experimental Intermedia; and international festivals/venues including Mexico City’s 1st International Sound Art Festival, NEXT in Bratislava, Cyberfest in St. Petersberg, and q-02 in Brussels. Parkins’ recordings have been published by Important Records, Atavistic, and Creative Sources, and her work has received support from American Composers Forum, NYSCA, the French-American Cultural Exchange, Meet the Composer, Harvestworks Digital Media Arts Center, and Frei und Hanseastadt Hamburg Kulturbehoerde. Parkins is on faculty at Goddard College’s MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts program.

—

Maile Colbert is a multi-media artist with a concentration on sound and video who relocated from Los Angeles, US to Lisbon, Portugal. She is a regular writer for Sounding Out!

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Wayback Sound Machine: Sound Through Time, Space, and Place— Maile Colbert

Sounding Out! Podcast #15: Listening to the Tuned City of Brussels, The First Night— Felicity Ford and Valeria Merlini

Sounding Out! Podcast #10: Interview with Theremin Master Eric Ross— Aaron Trammell

Sound as Art as Anti-environment

When I performed at the 2012 Computers and Writing Conference in Raleigh, North Carolina, I looked around during my fairly abstract 10-minute long improvisation featuring feedback loops, glitches, silences, and circuit-bent instruments, and I noticed the audience’s sometimes visible restlessness, discomfort, and even anxiety. This is a fairly common occurrence when I perform experimental sound art, particularly in contexts in which audiences expect “music” (you can hear my work at 38:30 in the video below). However, for an experimental sound artist to take offense to such reactions is, in my estimation, missing the point of the exercise. That sound art disrupts, agitates, and even offends is a powerfully reaffirming reminder that sound art transcends music and sound; it is a method of revelation, an act that surpasses logical communication, instead challenging the very nature of sound and perception.

.

As an artist, scholar, and fan, I am drawn toward sound and music that lures me into a new world, an unfamiliar way of being and knowing. Like Lewis Carroll’s Alice, I learn that the rules of my world no longer apply. This happened when I heard J Dilla’s Donuts album, and when I heard Madlib’s Medicine Show #3: Beat Konducta in Africa, when I heard Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. An artist that continually draws me down the rabbit hole is Walter Gross, an experimental sound/beat artist out of Los Angeles. His work changes the way I usually interact with sonic art, both in terms of his sound and in his approach to physical collage and handcrafted cassette packaging, Gross departs from the comfortable and familiar listening imparted by polished hi-fi 3-minute tracks with definitive beginnings and ends and discernible melodies. Gross instead propels listeners into very unusual (and pleasantly discomforting) soundscapes that demand attention. Almost counter-intuitively, Gross’s visual representations of his work intensify that experience. Consider his 2010 work, Dopamine:

Dopamine is likely a challenging piece for audiences, at least in terms of violating the dominant structures of music. The piece opens with disorienting use of panning, deliberately obscuring degraded audio, largely indiscernible movements and patterns, and so on. His video work likewise presents a fitting yet relatively unusual juxtaposition of youth and destruction, celebration and danger. In terms of both sound and sight, Gross’ work disrupts dominant musical sensibilities, challenging the very patterns and structures within which we can express ideas. He violates tradition, shakes off the canonical baggage carried by prevailing paradigms of Art and Music, and plunges audiences into unfamiliar sensory experiences that require metacognition, reflection, and examination of what sonic art is, and more importantly, what sonic art can be. Gross, in other words, seems to transcend the musician moniker and reach something else entirely. In what follows, I’d like to explore a (very brief) history of such artists, and begin to think about how to frame sonic art as immersion in what Marshall McLuhan called anti-environments: the unconscious environment as raised to conscious attention.

Sound as Art

There exists a strong tradition of experimental noise and sound art, particularly in 20th-century Western avant-garde movements. Futurists were arguably the first to consider noise as music in the European tradition, and were certainly influential in asking artists and audiences to become more aware of the changing social and sonic surroundings . In his 1913 manifesto-of-sorts titled “The Art of Noises,” Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo proposed an orchestral configuration that more aptly represented the range of sounds available to contemporary listeners, namely those sounds that accompanied industrialization and urbanization. The sounds of the Futurist orchestra would include “rumbles, roars, explosions, and crashes.” Russolo built devices called intonarumori to mechanically achieve and manipulate these sounds. His brother, Antonio Russolo, also enacted this new philosophy of modern found sound and composed Corale and Serenata.

Luigi Russolo and Ugo Piatti with the Intonarumori, 1913

Any inquiry of art as anti-environment would be incomplete without a discussion of the great anti-art movement, Dada. Like the Futurists before them, Dadaists used found sound and technology-as-art to violently disrupt conventions of art, beauty, and authorship within the white avant-garde community. Marcel Duchamp’s famous work, “Fountain,” is likely the most familiar Dadaist artifact to contemporary readers, yet the sound poetry of Kurt Schwitters and other Dadaist and Dada-inspired sound pieces such as Erwin Schulhoff’s 1922 work In Futurum (the middle movement of which contains only a rest and the notation “with feeling,” an undoubtable precursor to John Cage’s 4’33”, written 30 years later) created sonic spaces of innovation and strangeness that changed the way audiences listened to both voices and silences. The Russian Cubo-Futurists, especially zaumniks such as Alexei Kruchenykh, made similar ventures into anti-environments. Kruchenykh developed the sound art zaum, which he understood as a transrational language that undercut existing language systems in which the “word [had] been shackled…by its subordination to rational thought” (70). Zaum was a sort of linguistic anti-environment, one rooted in the notion that meaning resided first and foremost in the sound of a word rather than the denotative symbol system that emerged alongside the proliferation of print/visual culture. One could also not underemphasize the work of John Cage, from his prepared piano to his work with organic instruments.

John Cage and His “Prepared Piano,” Image courtesy of Flickr User William Cromar

The list of artists, genres, and movements engaged to some extent in the enterprise of anti-environment architecture could go on and be debated indefinitely: Free Jazz, Turntablism/Nu Jazz, Experimental Hip-Hop,Fluxus, Circuit Bending, Prepared Guitar, ProtoPunk, Punk, Post-Punk, New Wave, No Wave. . . in all of these diverse movements, the sonic artists share the tendency to create strange new worlds via sound; worlds that reveal social and technological environments that most people seem unaware of in the moment. This is why media theorist Marshall McLuhan called the artist “indispensible,” because the artist can tell us something about ourselves that we cannot know via ordinary means of perception. Sonic artists expose audiences to auditory phenomena, structures, juxtapositions, etc. that are to various extents hidden, obscured, or ignored as “noise.” The sonic artist is more than just a clever selector and (re)arranger of sound; s/he is a revelatory agent, exposing what is inaudible.

Art as Anti-environment

Anti-environments, however we might define and classify them, are vital not only to artistic communities themselves, but they are also vital to a society of fish in water. In his 1968 text, War and Peace in the Global Village, McLuhan asserts (among other things) that humans remain largely unaware of their new environments, likening them to fish in water: “one thing about which fish know exactly nothing is water, since they have no anti-environment which would enable them to perceive the element they live in” (175). In other words, humans seldom possess or practice a sense of awareness regarding their surroundings because there’s nothing against which surroundings may be contrasted. The “water” to McLuhan represented the various environments (physical, psychological, cultural) shaped by technological innovation, but we can—and should—extend the water metaphor to a range of hegemonic frameworks: constructions of gender, race, ability, and so on.

This essay is certainly not an attempt to generate some sort of evaluative rubric by which to judge artistic or sonic expression objectively. Rather, we might use the concept of anti-environments as a way to frame our subjective experiences and encounters with all sound, and begin listening to unfamiliar sounds as psychedelic (from Greek psyche- “mind” + deloun “reveal”) keys to illuminate the patterns and structures in which listeners exist. We must work to understand our environments and our place in them; if we are to engage critically with our culture, we must first understand existing (yet invisible) patterns and structures that surround us. And we are aided in this effort, in great part, by humanity’s great seekers of pattern recognition, the sonic-psychonautical messengers: the sonic artists.

Sound Artist Performing at Circuit Bending Workshop in Dayton, Ohio in 2009, Image Courtesy of Flickr User Vistavision

To return to the sound that inspired this meditation, Walter Gross (among others) is in many ways participating in and propelling the discourse of Leary and McLuhan, Schwitters and Schulhoff, Kruchenykh and Cage,Davis and Sun Ra, Madlib and J Dilla. Gross performs the sonic anti-environment, enacts the revelation of obscured sonic paradigms. For me, Gross can act as a sort of lens through which ordinary sonic patterns and structures become visible. I hear Flying Lotus, Bob Dylan, and The Minutemen differently after Gross. I hear my office, my home, my family’s voices differently after Gross. I hear patterns that weren’t audible before. After Gross, I become aware of how I am continuously trained to expect certain things from the sonic world: compartmentalized units of meaning, clearly stated origins of utterances, linear narratives, repeated/repeatable melodies, and so on.

Likewise, my own sonic art/scholarship approaches the use of sound to reveal the inaudible assumptions present in Western frameworks surrounding sonic production. I will conclude with an illustration of my own work and why sonic anti-environments are so central to my philosophy and method. One of my sonic works, “Toward an Object-Oriented Sonic Phenomenology,” was recently part of an exhibition titled Not For Human Consumption, curated by Julian Weaver of CRISAP in London. I recorded the sounds of a high mast lighting pole using contact microphones. Contact microphones do not “hear” like humans typically hear. Typical (dominant) notions of human hearing (and therefore of sound itself) involve the reception and interpretation of vibrations present in air. Contact microphones instead only interpret the vibrations in solid objects.

By listening through an object–through alien “ears,” so to speak– we can begin to critique the ways that we privilege listening via air, a listening that places humans at the center of the universe. We can consider the ways that sound has very real effects on humans with atypical hearing abilities and nonhuman objects. It is difficult to have such conversations if we never explore sonic anti-environments, if we never break through dominant epistemological models, if we never expose the limits of our own environments.

—

Featured Image: Beatrix*JAR in Dayton, Ohio, September 9, 2009, by Flickr User Vista Vision

—

Steven Hammer is a Ph.D. candidate in Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture at North Dakota State University in Fargo, ND, USA. His research deals with various aspects of sonic art, from exploring glitch and proto-glitch practices and theories (e.g., circuit bending), to understanding and producing sound from an object-oriented ontology (e.g., contact microphones). He also researches and facilitates trans-Atlantic translation collaborations between American, European, and African universities. He has multimedia publications with Enculturation, Sensory Studies, as well as forthcoming book chapters with Wiley/IEEE press, and IGI Global Publishing, and has performed creative and academic work at several conferences across North America, including the national Computers and Writing Conference and the Council for Programs in Technical and Scientific Communication. He performs experimental circuit-bent and sampler-based music under the moniker “patchbaydoor,” and has constructed and documented a number of hardware modification projects for his own artistic projects and for other artists in the upper Midwest United States. You can read/hear more atstevenrhammer.com

Recent Comments